Striking It Rich in the South Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O R R I E D a L E Official Newsletter of the Australian Corriedale Association Inc

Australian O R R I E D A L E Official Newsletter of the Australian Corriedale Association Inc. G.P.O. Box 75, Melbourne, Vic. 3001. web: www.corriedale.org.au FEBRUARY 2010 Phone: (03) 9817 6711 Email: [email protected] Australian Wool Innovation There is a lot of science FROM THE supporting wool in the home, PRESIDENT Much of my time in recent so we hope that the market months has been occupied will eventually wake up to with corresponding with the science. AWI. At our Federal Council meeting in July, we There is more to be done in invited the CEO of AWI, our relationship with AWI, Brenda McGahan to address but a start has been made and Corriedale breeders on the they are more than happy to role AWI is playing in communicate. We have just marketing Corriedale wool. sent them a selection of While she focussed mainly photos to use in their next on the new structure of AWI, promotional campaign. If general manager of AWI, anyone wishes to receive the Stuart McCullough, spoke AWI magazine „Beyond the about options for increasing Bale‟, contact demand for broader micron Communications manager, wools. Marius Cuming at [email protected] Since then, the ACA has Brenton J. Lush been communicating with Prince Charles promotes President AWI and other breeds about Wool marketing options for broader wools. This resulted Some of you may have heard It is always pleasant to be in an invitation to join other that Prince Charles has able to write a report and wool growers at an AWI launched a campaign in look at the positive news and Grower Forum in Sydney in Britain to promote wool. -

Agriculture in the Falkland Islands

Department of Agriculture Introduction Vision and Goals Falkland Islands Government The Falkland Islands supports an extensive range- Department of Agriculture land based agriculture sector. The main product is wool, with an EU approved abattoir producing Our Vision - A prosperous and self-reliant agricultural mutton and lamb for local and export markets and sector that creates opportunities for Falkland Islanders beef for local markets. and is highly valued locally and internationally. Our Mission - To foster a viable and internationally Wool produced in the Falklands is of superior competitive agricultural industry through integrated length and is regarded as some of the whitest and applied research, extension, business skills develop- cleanest wool in the world. ment and regulatory programmes. Goals Location . Provide research and extension support to improve . 483km from South America profitability and sustainability of farming businesses . Latitude: 51° - 53° South . Evaluate advances in animal and plant science for . Longitude 57° - 62° West adoption in the Falklands . 3,200 Falkland Island residents (2016 census) . Improve reproductive performance of sheep flocks . To improve genetics of sheep and cattle herds Geography through Artificial Insemination and Embryo Transfer . Total Land Area of 12,173km² programmes . Two main islands plus 778 smaller islands . To provide farms across the Falklands with superior . Topographically generally hilly sheep genetics via the National Stud Flock . Highest point is 705 m . To assist with marketing of wool through: . Administering The ‘Quality Falklands Wool’ Agriculture Climate scheme for excellence in wool preparation. Average annual rainfall range: 400—800mm . Sampling, analysis and certification of wool . Average temperature range: 2.2°C—9.4°C . -

Spinning Daily Presents Wool Washing

presents Wool Washing ©F+W Media, Inc. ■ All rights reserved ■ F+W Media grants permission for any or all pages in this issue to be copied for personal use Spin.Off ■ spinningdaily.com ■ 1 ou’re ready to take the plunge—literally—into raw fiber processing, and you know that wool can felt and Yshrink into a matted mess. But it doesn’t have to (after all, sheep get wet without shrinking). Let our experts guide you through selecting the proper animal fiber to meet your goals, then through washing wool without fear. It’s not nearly as difficult as you might think, and it produces great results. Have fun splashing in a basin of water. Watch wool transform from a greasy, dirty handful into a fluffy, puffy, silky mass. It’s like magic. Happy washing and spinning! Anne Merrow [email protected] 3 Choosing Fiber—Where to Start? by Diane Lalomia 8 Washing Wool Fleece by Rita Buchanan 11 Washing Wool by Robin Russo 14 On Washing Fleece by Judith MacKenzie Spin•O It’s about making yarn by hand! Spin•O magazine, published four times a year, features articles about the ancient and thriving cra of spinning. Each issue highlights the vibrant and diverse spinning community and explores the intricacies of spinning. spinningdaily.com ©F+W Media, Inc. ■ All rights reserved ■ F+W Media grants permission for any or all pages in this issue to be copied for personal use Spin.Off ■ spinningdaily.com ■ 2 Choosing Fiber— Where to Start? BY D IANE L ALOMIA o many of us choose the project after the yarn is spun, especially when we’re working with just 4 ounces Sof fi ber. -

James Macandrew of Otago Slippery Jim Or a Leader Staunch and True?

JAMES MACANDREW OF OTAGO SLIPPERY JIM OR A LEADER STAUNCH AND TRUE? BY RODERICK JOHN BUNCE A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2013 iii ABSTRACT James Macandrew, a Scotsman who migrated to Dunedin in 1851, was variously a businessman, twice Superintendent of Otago Province, an imprisoned bankrupt and a Minister of the Crown. He was an active participant in provincial and colonial politics for 36 years and was associated with most of the major political events in New Zealand during that time. Macandrew was a passionate and persuasive advocate for the speedy development of New Zealand’s infrastructure to stimulate the expansion of settlement. He initiated a steamer service between New Zealand and Australia in 1858 but was bankrupt by 1860. While Superintendent of Otago in 1860 and 1867–76 he was able to advance major harbour, transport and educational projects. As Minister of Public Works in George Grey’s Ministry from 1878–79 he promoted an extensive expansion of the country’s railway system. In Parliament, he was a staunch advocate of easier access to land for all settlers, and a promoter of liberal social legislation which was enacted a decade later by the Seddon Government. His life was interwoven with three influential settlers, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, Julius Vogel and George Grey, who variously dominated the political landscape. Macandrew has been portrayed as an opportunist who exploited these relationships, but this study will demonstrate that while he often served these men as a subordinate, as a mentor he influenced their political beliefs and behaviour. -

Farming on the Peatlands of the Falkland Islands

Farming on the peatlands of the Falkland Islands Jim McAdam Agri Food and Biosciences Institute, Queen’s University Belfast and the United Kingdom Falkland Islands Trust Abstract The Falkland Islands (Long 57-62°W; Lat51-53°S), land area 12,200km2 have a cool temperate (2.2°C.- 9.4°C), oceanic climate. Rainfall varies between 400-800mm and is lowest in spring. The islands were glaciated only on the highest ground with surrounding land affected by a periglacial environment. During the Post-glacial period acid, organic soils have formed mainly because of low temperature and the impervious clay-rich subsoil creating conditions which favour waterlogging. Upland peat, lowland peat or tussac (coastal) peat cover a large area of the entire land surface. Vegetation is typically dwarf shrub heath on drier soils and magellanic moorland on wetter soils. Agriculture is confined to extensive sheep farming in large enclosures (89% > c. 2000 ha). In the early days of the Colony (early 1800s) cattle roamed the islands and sheep were first introduced in the 1860s. They quickly became the main source of income on the (approx. 30) large farms which existed up until the early 1980s. Lord Shackleton’s Economic Survey (1976) recommending subdivision of the large farm units and transferring land ownership to local owners transformed the agricultural industry on the islands. Subsequently, the building of a certified abattoir in the early 2000s created further major opportunities. Traditionally, pasture improvement through reseeding and fertilising was practiced only on a very small scale. Recently the development of pastures with improved grasses and legumes coupled with rotational grazing has received much greater priority than previously. -

Riccarton Bush Act 1914

Reprint as at 20 May 2014 Riccarton Bush Act 1914 Local Act 1914 No 15 Date of assent 2 November 1914 Contents Page Title 2 Preamble 2 1 Short Title 3 2 Incorporation of Board 3 3 Constitution of Board [Repealed] 4 4 Terms of office of members of Board 4 4A When Board members come into office and vacate office 5 5 When seat of member of Board shall become vacant 5 6 Appointment of future members of Board 6 7 Appointment of first members of Board 6 8 First meeting of Board 7 9 Nomination of members of Board by members of the 7 family of John Deans 10 Procedure of Board 8 Note Changes authorised by subpart 2 of Part 2 of the Legislation Act 2012 have been made in this eprint. See the notes at the end of this eprint for further details. 1 Reprinted as at Riccarton Bush Act 1914 20 May 2014 10A Functions of Board 9 10B Powers relating to committees 9 10C Delegation of functions and powers 9 11 Common seal 10 12 Declaration of trust [Repealed] 11 13 Land to be called The Riccarton Bush. 11 14 Public entry to and conduct in Riccarton property 11 15 Powers of Board 11 16 Presumption that by-laws duly made 13 17 Presumption of intent in certain cases 13 18 Presumption of intent in other cases 13 19 Penalty 14 20 Christchurch City Council to make annual 14 grant [Repealed] Financial plans, statements of intent, and management plans 21 Definitions for sections 22 to 27 14 22 Requirements for financial plan 14 23 Council approval of financial plan 15 24 Statement of intent 16 25 Requirements for management plan 16 26 Board making and amendment of -

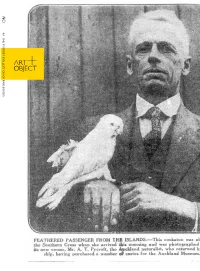

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

Taking the Stand

Taking the Stand Women as Witnesses in New Zealand’s Colonial Courts c.1840-1900 Elizabeth F. Bowyer A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington 2020 ii iii Acknowledgments This thesis could not have been written without the support I received from my supervisor Professor Charlotte Macdonald. Her extensive feedback and enthusiasm has made the year spent on this project one of the most rewarding and challenging experiences I have had. Thank you for being an unfailingly generous person who is so willing to impart knowledge on to your students. Thanks is also greatly owed to all the staff and postgraduate students at Victoria University of Wellington’s History Department. I am exceedingly grateful for the feedback and support you have all given me. I would not have been able to undertake this thesis without the financial support of the Jack Pearce Scholarship in English or New Zealand History, generously donated by Jack Pearce’s daughter, Brenda Joyce. Research trips were funded by Victoria University of Wellington Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Joint Research Committee. The Committee also funded my trip to the Australia and New Zealand Law and History Society Conference in Melbourne, alongside the society’s Kercher Scholarship. Attending this conference was an invaluable experience as I delved into the rich discipline of legal history. Thank you to my lovely parents, James and Helen, for always being on the other end of the phone when I need someone to chat to and for proof reading every word of this thesis. -

Issue 118 April 2020.Pdf

Falkland Islands Newsletter PPublishedublished bbyy TThehe FFalklandalkland IIslandsslands AAssociationssociation www.www.fi aassociation.comssociation.com NNoo 111818 AprilApril 22020020 ppeopleeople ppoliticsolitics fi sshinghing ttourismourism aagriculturegriculture eenvironmentnvironment 1111 1 Falkland Islands editorial Association Newsletter by FIA Chair John Duncan OBE Published by: The Falkland Islands Association, Falkland House, London SW1H OBH All change all change Tel 020 3764 0824 WELCOME to the spring edition of our Newsletter. The Islanders’ dedication to protecting honsec@fi association. their unique environment is a key theme to this edition, including the registration under the com Falklands fl ag of the RSS Sir Richard Attenborough, (below left) but also the Islanders’ ISSN 0262-9399 pride in their rich history and their determination to engage with the outside world, be that in sport, commerce, tourism or politics. Edited by: The turn of the year and the dawn of the new decade has brought changes and new Lisa Watson challenges both in Britain, with the election of the new government under Boris Johnson, Stanley and in Argentina with the return to political offi ce of Cristina de Kirchner and Daniel Falkland Islands Filmus. We hope that the latter, whose record of mischief making on Falklands issues lisawatsonfi @gmail.com is well known, will have taken note of Boris Johnson’s fi rm declaration in his traditional Christmas message to the Islanders that he is “Not in the business of ignoring referendum Website results”. Over the past 12 months the FIA Executive Committee (ExCo), all of whom are volunteers, have been working hard to ensure that whatever the future might bring our organisation was ready to support the Islanders eff ectively. -

Wool and Other Animal Fibers in South America

Proceedings of the Symposium on Natural Fibres 43 Wool and other animal fibers in South America Roberto Cardellino, Delta Consultants, Uruguay* and Joaquín Mueller** INTRODUCTION The South American sub-continent is a vast and variable area that includes 12 independent countries and many different ecological conditions, from tropical areas in the north to temperate climates in the centre and semi-desert conditions in the south. (Map 1). Map 1 – South America Table 1 – The importance of animal fi bers in South America Production in kgs Wool 143 700 000 Alpaca 4 055 595 Llama 3 342 866 Mohair 825 000 Vicuña 5 580 Guanaco 1 500 Source: Cardellino,R. based on SAGPyA, SUL, ODEPA, IICA, IWTO Wool is by far the most important ani- mal fi ber in South America; however other animal fi bers like alpaca, llama, and mohair are also produced in large quantities, whereas vicuña, guanaco, angora and cashmere have a great potential for development but the amount produced at present is low (Table 1). The production of wool and other specialty of fi bers is concentrated in the Southern Cone of the sub-continent (Argentina, Uruguay, Chile and south of Brazil), where climate is temperate or deserted. Further north, with the exception of the Altiplano region, (the highlands of the Andes mountains), the production of these animal fi bers is not possible due to the tropical climatic conditions. * Delta Consultants, Director ** National Institute for Agriculture Technology, INTA 44 Proceedings of the Symposium on Natural Fibres Map 2 – South America: sheep producing areas THE PRODUCTION OF WOOL The main areas in South America producing wool are shown in Map 2. -

Genetic Variation and Covariation in Productive Characters of New Zealand Romney Marsh Sheep Alexander Lindsay Rae Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1950 Genetic variation and covariation in productive characters of New Zealand Romney Marsh sheep Alexander Lindsay Rae Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Veterinary Pathology and Pathobiology Commons Recommended Citation Rae, Alexander Lindsay, "Genetic variation and covariation in productive characters of New Zealand Romney Marsh sheep" (1950). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14622. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14622 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

The Riccarton Bush Pūtaringamotu Management Plan 2015

December 2015 THE RICCARTON BUSH / PŪTARINGAMOTU MANAGEMENT PLAN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS KEY TERMS USED IN THIS MANAGEMENT PLAN Key stakeholders, user groups, Christchurch City Council ABBREVIATED NAME FULL NAME COVERING the Property The Riccarton Bush The whole site under the staff, Ngāi Tahu and the general public were consulted in the property / Pūtaringamotu administration of the Trust preparation of the Riccarton Bush Management Plan and the the Bush The Riccarton Bush The whole of the native input from all has been highly valued. The people listed to the indigenous forest / forest area lower right on this page, in particular, have contributed Pūtaringamotu the House Riccarton House The Riccarton House significantly to the plan’s re-development. building the Cottage Deans Cottage The Deans Cottage building PUBLIC NOTIFICATION and PLAN APPROVAL the Grounds Riccarton House and The grounds around the Cottage Grounds House and the Cottage The draft management plan was publicised publicly in but not including the Bush accordance with section 26(4) of the Riccarton Bush Act 1914 the Trust The Riccarton Bush Trust The Riccarton Bush Trustees (“the Board”) from 14 September to 23 November 2015. Three written submissions were received. The Riccarton Bush Trust The Riccarton Bush Trust Management Plan Working Party approved the draft management plan as the operative Mike Mora Trust Deputy Chairman management plan at the Trust’s board meeting on 2 Tim Deans Trustee December 2015. Tony Gemmill Trustee Dr Brian P Molloy Trustee DISCLAIMER: The content of this plan is not necessarily the Jon Ward Manager complete and accurate record of The Riccarton Bush property.