Taking the Stand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Striking It Rich in the South Island

• 17 !It you ean almost hear the tape STRIKING IT RICH IN THE Ie voices that speak of Charlie or SOUTH ISLAND GRASSLAND, 1848-1914 Ie of those voiees on tape. As I voice of the storyteller, the oral by I born in Montana, or the Doigs Jim McAloon [which being a not-inconceivable ledges as an essential life-force, Ifyou go to the churchyard at emiek, in the Scottish Highland eounty of vould sit and talk for hours while Ross, as well as the memorial to the evicted tenants ofGlenealvie, you will, if Id listen for just as long. you look, see a tombstone: "Erected by Donald Ross, Burkes Pass, New Zealand, in loving memory ofhis father and mother and also ofhis brothers.. .. " Donald Ross was born third son of this erafting family in 1848 and wentto ED New Zealand, as the tombstone informs us, in 1879. Burkes Pass is in the inland central South Island plain known as the Maekenzie eountry, and Donald ofa Western Mind. New York: Ross was one ofa number ofsheep farmers there who left a substantial fortune. He died in 1926, and his estate was valued at £26464 which may not seem a I: Penguin Books Australia, Ltd., great deal but was in the top 5%. I want to argue that in his passage from humble eircumstanees to some wealth Ross was far from unusual among those ~hang;ng Literary Perceptions of who prospered in the South Island grasslands. ishers,1984. This view differs from mueh writing on the upper elass in the nineteenth lew York: The Lyons Press, 1998. -

James Macandrew of Otago Slippery Jim Or a Leader Staunch and True?

JAMES MACANDREW OF OTAGO SLIPPERY JIM OR A LEADER STAUNCH AND TRUE? BY RODERICK JOHN BUNCE A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2013 iii ABSTRACT James Macandrew, a Scotsman who migrated to Dunedin in 1851, was variously a businessman, twice Superintendent of Otago Province, an imprisoned bankrupt and a Minister of the Crown. He was an active participant in provincial and colonial politics for 36 years and was associated with most of the major political events in New Zealand during that time. Macandrew was a passionate and persuasive advocate for the speedy development of New Zealand’s infrastructure to stimulate the expansion of settlement. He initiated a steamer service between New Zealand and Australia in 1858 but was bankrupt by 1860. While Superintendent of Otago in 1860 and 1867–76 he was able to advance major harbour, transport and educational projects. As Minister of Public Works in George Grey’s Ministry from 1878–79 he promoted an extensive expansion of the country’s railway system. In Parliament, he was a staunch advocate of easier access to land for all settlers, and a promoter of liberal social legislation which was enacted a decade later by the Seddon Government. His life was interwoven with three influential settlers, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, Julius Vogel and George Grey, who variously dominated the political landscape. Macandrew has been portrayed as an opportunist who exploited these relationships, but this study will demonstrate that while he often served these men as a subordinate, as a mentor he influenced their political beliefs and behaviour. -

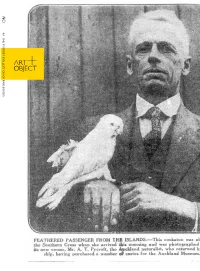

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

1 Drawings and Signatures of Moko by Mäori in the Early 19Th Century

KI TÖ RINGA KI NGÄ RÄKAU Ä TE PÄKEHÄ? 1 DRAWINGS AND SIGNATURES OF MOKO BY MÄORI IN THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY NGÄRINO ELLIS (Ngäpuhi, Ngäti Porou) University of Auckland Ko Räkaumangamanga te maunga, Ko Ipipiri te moana, Ko Te Räwhiti te marae, Ko Ngäti Kuta te hapü, Ko Ngäpuhi te iwi, Ko Te Nana te tupuna, Ko Ngä Taiapa Rino o Te Poka o Whata Paraua ahau. Räkaumangamanga is my mountain, Ipipiri is my sea, Te Räwhiti is my marae, Ngäti Kuta is my sub-tribe, Ngäpuhi is my tribe, Te Nana is my ancestor, Ngä Taiapa Rino o Te Poka o Whata Paraua (Ngärino) is my name. In May 2013, on a beautiful Monday morning, around 150 members of hapü ‘sub-tribes’ from around the Bay of Islands, including Ngäti Manu and Te Kapotai and the two hapü of Te Rawhiti (Ngäti Kuta and Patu Keha), boarded a hired ferry at Opua. Along with members of the Waitangi Tribunal and their retinue, the group visited sacred and important hapü sites. We began on our precious moana ‘ocean’ and ended up travelling by bus inland to marae ‘ancestral community hubs’ at Waikare and Karetu. This was to be a historic moment as we heard from our kuia ‘female elders’ and kaumätua ‘male elders’ about the effects of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi) 1840 and its insidious legacies for us today. The next day our kaikörero ‘speakers’ began four days of hearings, in which they frequently referred to documents which our tüpuna ‘ancestors’ had signed. In their Briefs of Evidence, they referred to the sacred marks their ancestors had made from their moko ‘tattoo’ on those documents, especially Te Tiriti and Te Wakaputanga (the Declaration of Independence) 1835. -

Mt Cook, Wellington - a History

Mt Cook, Wellington - A History Peter Cooke © WCC, 2006 The area now known as Mt Cook is defined by the hill, Pukeahu, which was renamed by early settlers after Capt James Cook, RN.1 On it was a pa, long abandoned when first seen by Pakeha eyes. Mt Cook is now a suburb of Wellington bounded by the town belt in the west (Central and Prince of Wales Parks) and the Wellington College and Government House Reserves in the east. It sits between the suburbs of Te Aro, Brooklyn and Newtown, or the arterial routes of Webb/Buckle Streets to the north, Brooklyn Hill Road in the west, John Street in the south and lower Adelaide Road in the east. Any expansion of this part of the city was constrained by the sandwiching Town Belts either side, which “played a similar role to the medieval city wall.”2 A range of official functions gave Mount Cook – the hill – early identity (and form). A military role was envisaged when the NZ Company first saw it, the company’s 1840 map showing the hill reserved for military purposes. Troops were stationed there temporarily from 1843 but barracks on and below the hill gave Mt Cook a permanent martial role and, though this role has been significantly whittled down, HMNZS Olphert still operates from Buckle St in 2006.3 Timber milled in Tasmania was brought over for the stockade and military quarters erected on Mt Cook by 1852. “The defences were between 3/4 of a mile and a mile round and the buildings were reinforced with prison-made bricks and loopholed.”4 Its other duties in the Twentieth Century were various: Mt Cook -

Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This Is Part 1 of a Two Part Trail

Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This is Part 1 of a two part trail. Part 2 is contained in a separate booklet. This part of the trail will take two to three hours to drive. There is some walking involved as well but it is of a generally easy nature. It features the southern suburbs - Kaiwharawhara, Ngaio, Crofton Downs, Wilton and Wadestown - that largely surround and overlook the Kaiwharawhara Stream. Part 2 follows the Old Porirua Road through Ngaio, Khandallah and Johnsonville, Glenside and Tawa with deviations to Ohariu, Grenada Village, Paparangi and Newlands. The trail finishes at Ngauranga. Main features of the trail Bridle Track Kaiwharawhara Magazine Crofton Wellington-Manawatu Railway (Johnsonville Line) Wilton House Panels describing the history of the major centres Key Registered as a historic place by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust / Pouhere Taonga Part 1 Listed as a heritage item in the Wellington City District Plan Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This is Part 1 of a two part trail. Part 2 is contained in a separate booklet. This part of the trail will take two to three hours to drive. There is some walking involved as well but it is of a generally easy nature. It features the southern suburbs - Kaiwharawhara, Ngaio, Crofton Downs, Wilton and Wadestown - that largely surround and overlook the Kaiwharawhara Stream. Part 2 follows the Old Porirua Road through Ngaio, Khandallah and Johnsonville, Glenside and Tawa with deviations to Ohariu, Grenada Village, Paparangi and Newlands. -

Pdf600.6Kbautumn 2014

Newsletter Autumn 2014 STAFF UPDATE J.D. Stout Research Fellow 2014 Welcome to Vincent O’Malley, the 2014 JD Stout Research Fellow. Vincent is writing a history of the Waikato War. His previous books include: The Meeting Place: Māori and Pākehā Encounters, 1642-1840 (Auckland University Press), which was a finalist in the general non- fiction category at the 2013 NZ Post Book Awards; Agents of Autonomy: Māori Committees in the Nineteenth Century (Huia); a co-authored work (with David Armstrong), The Beating Heart: A Political and Socio-Economic History of Te Arawa (Huia); and an edited volume (with Bruce Stirling and Wally Penetito), The Treaty of Waitangi Companion: Māori and Pākehā from Tasman to Today (Auckland University Press). Vincent has over two decades’ involvement as a professional historian in the Treaty of Waitangi claims process, including since 2004 as director of the research consultancy HistoryWorks. In 2004 he became the first PhD graduate in New Zealand Studies through the Stout Research Centre. New Adjunct Professors John Weaver A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, John Weaver is delighted to be joining the Stout Centre as an Adjunct Research Professor. Currently he is working through the government archives on the economic reforms of Fourth Labour, in order to describe how radical measures were implemented. Since 1999, he has lectured several times at the Stout. His academic home is McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario where he is one of eight Distinguished University Professors. His recent books include The Great Land Rush and the Marking of the Modern World, 1650-1900 and A Sadly Troubled History: The Meanings of Suicide in the Modern Age. -

Whale Fishing and the Economic Development of Early Wellington

‘That Glorious Stinking Stuff . .’: Whale Fishing and the Economic Development of Early Wellington BRAD PAtterson Victoria University of Wellington For generations of New Zealand school children, brought up on texts such as Our Country or The Changing Land,1 the sealers and whalers were itinerants who came after the Maori canoe migration phase, but before European settlement proper began. And the depiction of whale fishing has been an overly romantic one, owing much to what might be termed the Herman Melville tradition.2 In the words of British whaling historian Gordon Jackson, there has been a tendency to portray pursuit of the marine Leviathan by puny men more as ‘an Act of God . than as capital in the pursuit of profit’.3 To date, with the exception of Harry Morton’s monumental The Whale’s Wake,4 there has been little substantial published scholarly writing on the nineteenth century New Zealand whaling industry. Certainly, in the early 1900s Robert McNab5 published several vital compilations of relevant documents. Then, in 1965, L.S. Rickard6 produced a short popular account of the trade. But apart from several small but detailed recent monographs by Rhys Richards,7 the whalers continue to feature almost as a footnote to general and regional histories. In the present paper the primary emphasis will be on what happened after the first systematic colonisers arrived, not before. It will be suggested that in at least one New Zealand settlement, Wellington (or Port Nicholson), whale fishing continued to be of major economic importance for most of the founding decade. It will also be contended that the industry helped ensure the viability of the settlement in the short term, and that there were long-term structural legacies for the evolving settler economy. -

Fobsc Newsletter 76 Nov13

FRIENDS of BOLTON STREET MEMORIAL PARK INCORPORATED PO BOX 12 426, WELLINGTON, 6144, NEW ZEALAND http://www.boltoncemetery.org.nz NEWSLETTER No 76 NOVEMBER 2013 Editor: David Dunsheath CEMETERY REPAIRS COMPLETED DURING 2012/13 Using the annual grant from the Early Settlers Fund within the budget of the Wellington City Council, the following repairs were made to tombstones and graves during the Council’s last financial year ending June 2013. While the Fund is expected to be fully utilised in the current financial year, provision has been made in the Council’s budget for on-going repairs as indicated in the Manager’s report in this issue. The Friends are extremely grateful for this commitment by the Council to the important heritage work in the cemetery. IN THIS ISSUE: Cemetery Repairs ……………....cover AGM Guest Presentation …………...2 Unknown Aileen …………………....3 William Beetham Portrait Artist ……4 Terry Brandon Obituary …………....5 Botanic Gardens Manager’s Report ..6 Working Bees ...…………………….8 Masonry repairs were undertaken by Kim Stops of Headstone World, who has mended many of our heritage graves. Recent breakages were repaired on marble memorials for Jane Elizabeth Allen by the Easdale fence, Alfred Canning Shaw on the Carr Path, Elizabeth & William Ebden on the Friends Path and Fred & Mary Tiller near Robertson Way. We also began to Restored Smith tombstone repair memorials with concrete back (N14-08). Photo: David Dunsheath supports which were now crumbling. FoBSMP newsletter 76 Nov2013.doc 1 Printing of this newsletter donated by www.boltoncemetery.org.nz These were for Jane Fitzgerald (Carr Path) and for Margaret & John Smith (on Robertson Way). -

Private Acts of Parliament

653 PRIVATE ACTS OF PARLIAMENT Rt Hon Sir Ivor Richardson* The article explains the role that Private Acts of Parliament have played and still play. It does so by recounting their historical development and then discussing some 70 Bills and their progress through the Parliamentary processes. The narrative follows a broad subject-matter classification of Private Bills which are promoted by private individuals, local institutions, companies, particular charities, associations and other corporate bodies for their own benefit, whereas Public Bills and Local Bills are directed to the functioning of Central Government and Local Government respectively. I INTRODUCTION Private Acts of Parliament have waxed and waned in their apparent significance and in the numbers of highlight cases since New Zealand gained responsible government in 1856. They remain a significant function of Parliament and it is worthwhile reflecting on their historical background and the role they have played and still play there as well as in the affairs of the particular individuals and corporate bodies. McGee classifies Bills into four categories: Government Bills, dealing with a matter of public policy initiated by a Minister; Member's Bills, dealing with a matter of public policy introduced by a Member who is not a Minister; Local Bills, promoted by a local authority and confined in their effects to a particular locality; and Private Bills, promoted by a person or body of persons for the particular interest of that person or body of persons.1 Burrows and Carter explain that the three main categories of Acts of Parliament are Public, Local and Private: Public Acts affect the public at large; * Distinguished Fellow, VUW Faculty of Law. -

St Pauls Papanui Cemetery

St. Paul’s Anglican Cemetery Tour Papanui Compiled by Richard L. N. Greenaway June 2007 St. Paul’s Papanui Cemetery 2007 1 Area 1 Row A No 1 Shead Just to the left as one enters St. Paul’s cemetery there is a gravestone with the wording: ‘In loving memory of Thomas Edward Shead, beloved son of J. and A. Shead, died 11 October 1882, aged 11 years and six months. Late of Phila., Penn., U.S.A.’ Atop the monument there is a striking sculpture of a handsome vigorous boy. It would seem that Thomas died of an illness. His parents, Joseph and Annie Shead, were living in Papanui at the time of their son’s death but do not appear to have remained long. No. 15 Thomson Edinburgh-born and the son of a printer, William Thomson worked as an accountant in Glasgow. He emigrated with his family, arrived in Canterbury in 1853 on the Hampshire, a vessel of about 600 tons. Theirs had been ‘a protracted voyage of five months’. Thomson attended the ball on Queen Victoria’s birthday – on 24 May – in Highland costume. The Lyttelton Maori ‘hearing of his costume, gathered along Norwich Quay to see the Taipo coming – rather peculiar considering their style of dress’. Thomson bought a property, ‘Hemingford’, at Governors Bay. It became the famous and beautiful property of sheepfarmer, scientist and conservationist T. H. Potts and was - and is - known as ‘Ohinetahi’. To get home the family had to travel by boat or walk along a very narrow track and pass through the big and little Rapaki Maori pas. -

Wellington Civil Proceedings Action Register January 1874 to December 1878 Archives New Zealand Reference AAOM 6043 W3265 2/1A

Pandora Research www.nzpictures.co.nz Wellington Civil Proceedings Action Register January 1874 to December 1878 Archives New Zealand Reference AAOM 6043 W3265 2/1A This Register covers a similar time period to that of AAOM 6043 W3265 1/1 and appears to record the dates of various legal processes for each case. Many cases are probably the same but not all and for this reason a complete index to this volume will be undertaken up to c1880. Date No. Plaintiff Defendant 1874 Jan 09 826 Francis Henry Bradey, Wellington, settler Mary Nevin and Duncan Nevin, Wellington, settlers 1874 Jan 09 827 William Tonks jun., and John Beck, Wellington David Macquarie Newcastle, shipowner 1874 Jan 12 828 John Tully Ngatuere, Wi Tutere, Eraita te Here, Raniera Roimata & others 1874 Jan 14 829 Archibald & Campbell Colquhoun, infants (by Peter Campbell) John Houghton and John Campbell 1874 Jan 16 830 Ann Evans, Waihi, Taranaki, widow Richard Lynch, Patea, Taranaki, settler 1874 Jan 16 831 George Henry Tribe, Wanganui, newspaper proprietor William Hogg Watt, Wanganui, newspaper proprietor 1874 Jan 22 832 Samuel Lowden Broadbent & Jerry Hayes Siggs, Hawera, settlers William Evans Dive, Hoods Bay, Pelorus Sound 1874 Jan 22 833 John Duthie, Wanganui, merchant William Hogg Watt, Wanganui, settler 1874 Jan 22 834 John Duthie, Wanganui, merchant Thomas Watson Ferry, Wanganui, newspaper publisher 1874 Jan 24 835 John Sutherland, Mataikuna, farmer George Crawford, Wellington, merchant 1874 Jan 24 836 Sarah Roberts admix. H. B. Roberts, Wanganui, solicitor Celia Atkinson, Wanganui, widow 1874 Jan 24 837 Sarah Roberts admix., H. B. Roberts, Wanganui, solicitor Celia Atkinson, executrix David Atkinson, Wanganui 1874 Feb 07 838 John Davis, Foxton, sheepfarmer Charles Howe, Wirokino, shoemaker 1874 Feb 12 839 Thomas Burt, Upper Hutt, storekeeper William Booth, Upper Hutt, Mill Sawyer 1874 Mar 11 840 Archibald Paisley Stuart, Wellington, merchant Walter & James Gibson, Waipapa, sheepfarmers & E.