A Geography of Participation in IT-Mediated Crowds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gep Outlook Report 2019

INDEX INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 GLOBAL BUSINESS AND MACROECONOMIC TRENDS 7 Introduction 7 The Macro Indicators 7 Key Drivers of Supply Chain and Price Volatility 10 Implications of Global Economic and Geopolitical Trends 14 2019 TRENDS IN PROCUREMENT DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION 16 Digital-First Mindset 16 “Agile” Procurement as Main Partner to Technology and Overall Business 17 Continued Market Domination of Source-to-Pay Applications 17 Guided Workflows to Enhance Procurement Results and End-User Experience 18 Expansion of Cloud Procurement Solutions Into Direct Procurement and Supply Chain 19 Category-Centric Transformation 19 Disruptive Technologies to Strengthen Data Science Capabilities 20 Disruptive Technologies to Strengthen Smart Automation Capabilities 22 Digitally Savvy, Economically Aware and Analytically Capable Talent 23 SUPPLY MARKET TRENDS AND INSIGHTS BY CATEGORY 24 Direct Materials and Commodities 24 Logistics 27 Information Technology and Telecommunications 31 General and Professional Services 34 Marketing and Advertising 38 CAPEX and Construction 41 MRO 43 Packaging 46 Chemicals 48 Introduction “Praemonitus praemunitus.” Loosely translated from Latin, this means: To be forewarned is to be forearmed. That is, in essence, the mission of our annual GEP Outlook, now in its seventh year of publication. And in today’s climate of sustained volatility, busy procurement and supply chain executives need every available tool they can get to help navigate global supply markets and to guide their teams through opinion and hype. Our annual Outlook report is designed to be a practical planning tool with respect to both macro- level supply chain dynamics as well as category and commodity trends and innovations. It is based on GEP’s collective experience in managing over $125 billion in spend across all sectors and geographies. -

Boosting Creativity Through Digital Disruption? the Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field. Original Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field. / Monaci, Sara. - In: WESTMINSTER PAPERS IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE. - ISSN 1744-6716. - ELETTRONICO. - 11(1)(2016), pp. 49-64. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2656317 since: 2016-11-18T14:44:35Z Publisher: Westminster University Press Published DOI:10.16997/wpcc.218 Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 06 December 2018 Monaci, S. (2016). Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 11(1), 49–64, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.218 RESEARCH ARTICLE Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field Sara Monaci Politecnico di Torino, Italy [email protected] Web technologies transformed the media production field in many aspects: audio- visual contents in particular, are at the centre of a reshaping process involv- ing their use, creative production, distribution and consumption. The effects of digital disruption are revealed though a media production field characterized by an increasing complexity. Co-creation environments emerge as new digital inter- mediaries, which may integrate the open collaboration of peers with the need to identify new ways of recognising and enhancing creativity in a sustainable way. -

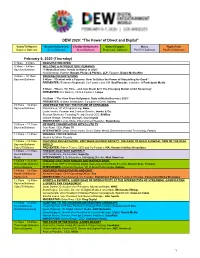

DEW 2020: “The Power of Direct and Digital”

DEW 2020: “The Power of Direct and Digital” Video/TV/Movies Brands/Advertising Creators/Influencers Games/Esports Music RightsTech Bayview Ballroom Sierra Ballroom Sierra Ballroom Promenade Ballroom Pacific II Ballroom Pacific III Ballroom February 6, 2020 (Thursday) 8:30am – 9:30am REGISTRATION OPEN 9:30am – 9:40am WELCOME & INTRODUCTORY REMARKS Bayview Ballroom “5 Media Business Trends to Watch in 2020” Ned Sherman, Partner, Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP; Founder, Digital Media Wire 9:40am – 10:10am OPENING PRESENTATIONS Bayview Ballroom 9:40am - “Content with a Purpose: How To Utilize the Power of Storytelling for Good” PRESENTER: Shabnam Mogharabi, Co-Founder and GM, SoulPancake, a division of Participant Media 9:50am - “Music, TV, Film... and now Street Art? The Emerging Market of Art Streaming” PRESENTER: Dot Bustelo, CEO & Founder, Loupe 10:00am - “The View From Hollywood: State of Media Business 2020” PRESENTER: Andrew Wallenstein, Co-Editor-in-Chief, Variety 10:15am – 10:45am VIEW FROM THE TOP: THE FUTURE OF STREAMING Bayview Ballroom Rob Holmes, VP of Programming, Roku Leslie Iwerks, Founder and Creative Director, Iwerks & Co. Soumya Sriraman, Founding President and CEO, BritBox Joanne Waage, General Manager, Crunchyroll MODERATOR: Lucas Shaw, Entertainment Reporter, Bloomberg 10:45am – 11:15am KEYNOTE CONVERSATION WITH PLUTO TV Bayview Ballroom Tom Ryan, CEO, Pluto TV INTERVIEWER: Dawn Chmielewski, Senior Editor Media, Entertainment and Technology, Forbes 11:15am – 11:45am MORNING COFFEE BREAK Hosted by Music Reports 11:45am – 12:15pm FEATURED PRESENTATION: SOFTWARE DEFINED SOCIETY: THE RACE TO BUILD A DIGITAL TWIN OF THE REAL Bayview Ballroom WORLD Video/TV/Movies PRESENTER: Robert Tercek, CEO and Co-Founder, VIA: Venture Intellect Associates 11:45am – 12:15pm FIRESIDE CHAT WITH SUPERFLY Sierra Ballroom Rich Goodstone, Co-Founder, Superfly Music INTERVIEWER: Seth Schachner, Managing Director, Strat Americas 11:45am – 12:15pm FIRESIDE CHAT WITH ROBLOX AND WARNER BROS. -

Shortlist (Entertainment Lions)

Shortlist (Entertainment Lions) Cat. En Title Client Product Entrant Country Agency Production No try Company Company No A01 (Cinema & Theatrical: Fiction Film) A01/ 00 CANDIES TARJETA TARJETA BBDO ARGENTI BBDO 002 11 NARANJA NARANJA ARGENTINA NA ARGENTINA 9 Buenos Aires Buenos Aires A01/ 01 CINERGÍA II GAS CINERGÍA ARENA MEDIA SPAIN ARENA EL TERRAT 007 75 NATURAL II Madrid MEDIA Madrid Barcelona 0 FENOSA A02 (Cinema & Theatrical: Non-Fiction Film) A02/ 01 FREE THE UNILEVER PERSIL / MULLENLOWE UNITED MULLENLOW RSA FILMS 003 00 KIDS OMO GROUP London KINGDO E GROUP London 5 M London A04 (TV & Broadcast: Fiction 15 minutes or under in Length) A04/ 00 ORANGEAID - NTUC ORANGEA BBH SINGAPO BBH DOGHOUSE7 008 32 LAST DAY OF INCOME ID SINGAPORE RE SINGAPORE 3 PICTURES 0 SCHOOL BURSARY Selangor AWARD A04/ 01 MOG'S SAINSBUR SUPERMA AMVBBDO UNITED AMVBBDO OUTSIDER 013 39 CALAMITY Y'S RKET London KINGDO London London 7 M A05 (TV & Broadcast: Fiction 15 minutes or over in Length) A05/ 00 LOVE LIKE MONDELÉ LACTA OGILVYONE GREECE OGILVYONE FOSS 001 59 THERE'S NO Z WORLDWIDE WORLDWIDE PRODUCTIO 1 TOMORROW INTERNATI ATHENS ATHENS NS Athens ONAL A06 (TV & Broadcast: Non-Fiction Series ) A06/ 00 RISE NIKE NIKE RISE AKQA London UNITED AKQA London FIRECRACKE 005 21 PHILIPPINES BASKETBA KINGDO R FILMS 8 LL M London / CENTRAL DIGITAL Makati A07 (TV & Broadcast: Non-Fiction 15 minutes or under in Length) A07/ 01 BEHIND THE IBCC CORPORA OGILVY BRAZIL OGILVY CONSPIRAÇ 002 62 T-SHIRT TE IMAGE BRASIL São BRASIL São ÃO FILMES 2 Paulo Paulo São Paulo / JAMUTE AUDIO -

Local Clients Choose Television Over Other Media

www.cablespots.net Published Daily For Subscriptions, call 1-888-884-2630 [email protected] $300 Per Year Copyright 2018 Wednesday, July 11, 2018 LOCAL CLIENTS CHOOSE TELEVISION OVER OTHER MEDIA BROADCAST, CABLE TV TOP DIGITAL SPENDING ADVERTISER NEWS Digital may have more buzz than television in 2018, but PepsiCo’s fiscal second-quarter earnings beat analysts’ both broadcast and cable TV are leading where it really expectations as sales of Cheetos and other salty snacks matters. Each gets far more ad dollars, on average, from continued to offset its slumping soft drinks business. The local advertisers than any form of online media. maker of Pepsi, Gatorade, Mountain Dew and Tropicana Borrell Associates’ annual survey of small- and said yesterday that sales volume declined for its North medium-sized businesses in local markets across the U.S. American beverage unit in the second quarter. CEO Indra shows they spend an average of $176,105 on Nooyi last quarter placed the blame for slow- broadcast TV each year, far outpacing all other ing sales on Coca-Cola’s increased spending marketing options. Local cable TV advertising on advertising. PepsiCo’s net revenue rose 2.4 ranks second, capturing slightly more than a percent to $16.09 billion, of which $5.19 billion third of what broadcast does. Borrell found local came from its beverage business and beat Wall clients allocated an average of $68,123 to cable Street expectations. The company said that it TV spots each year. will increase the marketing budget behind Pepsi The survey also says local advertisers are going into the second half of the year.. -

2015 Sponsorship Overview and Opportunities

2015 Sponsorship Overview and Opportunities 1 // 2015 Sponsorship Overview and Opportunities ABOUT THE ANA 2015 CONFERENCE PORTFOLIO The ANA (Association of National Advertisers) provides leadership that advances Brand Masters marketing excellence and shapes the future of the industry. Founded in 1910, February 4–6 // The Ritz Carlton- Laguna Niguel // Dana Point, CA the ANA’s membership includes more than 640 companies with 10,000 brands that collectively spend over $250 billion in marketing and advertising. The ANA Media Leadership also includes the Business Marketing Association (BMA) and the Brand Activation March 4–6 // The Diplomat Resort & Spa // Hollywood, FL Association (BAA) which operate as divisions of the ANA. The ANA advances the Advertising Law & Public Policy interests of marketers and promotes and protects the well-being of the marketing March 31–April 1 // The Four Seasons // Washington, DC community. For more information, visit www.ana.net, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram. **BAA Annual Marketing Conference April 13–15 // The Westin Chicago River North // Chicago, IL ABOUT SPONSORING WITH THE ANA Advertising Financial Management April 26–29 // Arizona Biltmore // Phoenix, AZ Sponsorship with the ANA allows companies to have exposure and engage with **BMA Annual Conference senior level client side marketers – our members. Conference sponsorships at May 27–29 // Sheraton Chicago Hotel & Towers // Chicago, IL our national industry conferences provide opportunities to have access to ANA members -

Organizing for Growth in a Digital Age Looking at a Changing Agency

the international ist FOR ADVERTISING, MARKETING + MEDIA PROFESSIONALS Global Alliance With NUMBER75 2015 innovators 2015 Organizing for Growth in a Digital Age Looking at a Changing Agency Business in a New Light The Race for Accountability in an Era of Transformation Warning to Global Marketers about Media Agency Management www.internationalistmagazine.com 8 | Organizing for Growth in a Digital Age the 12 | Lenovo’s CMO David Roman Embraces a “Never Stand Still” Brand Attitude 14 | Dentsu’s Tim Andree Looks at a Changing Agency Business in a New inteLightr nationalist FEATURES 17 | GE’s Andy Markowitz Discusses the Race for Accountability in an Era of Transformation www.internationalistmagazine.com 22 | Meet the 2015 Innovators! This extraordinary group of 30 individuals from all corners of the globe are embracing change and making a difference for their agencies and for their clients. 46 | COMMENTARY: John Billett Issues a Stern Warning to Global Marketers about Media Agency Management 2015: 75 SUBSCRIBE ONLINE Group discounts Editor’s Letter | 4 available for bulk shipping. Frontlines | 6 Globetrotters | 18 DEPARTMENTS People & Places | 50 50 ©2015. STAFF Excerpts may be quoted with proper attribution deborah malone FOUNDER [email protected] to the internationalist. erin oates CONTRIBUTING EDITOR [email protected] The internationalist is amanda crowley CONTRIBUTING EDITOR [email protected] a publication for and by international les margulis CONTRIBUTING EDITOR [email protected] -

Digital Cinema and the Legacy of George Lucas

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Digital cinema and the legacy of George Lucas Willis, Daniel Award date: 2021 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information. -

Brand Masters Conference

2014 ANA Brand Masters Conference February 26–28 | The Westin Diplomat Resort & Spa | Hollywood, Fla. Download the ANA mobile app — e.ana.net We’ll be live tweeting throughout the conference (@ANAMarketers), as well as posting photos and other information at facebook.com/ANA. Join the conversation online using the hashtag #ANABrand. www.ana.net Table of Contents 2014 ANA Brand Masters Conference presented by Mashable Agenda ............................................................................ pg 3 Speaker Bios .................................................................... pg 7 Attendee List ..................................................................pg 15 ANA Member Benefits .................................................... pg 33 Sponsor Information ........................................................pg 37 www.ana.net 1 Agenda 2014 ANA Brand Masters Conference presented by Mashable WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 26 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 27 WELCOME/OPENING REMARKS Seth Rogin Registration Opens (3:00 p.m.) Breakfast (7:30 a.m.) Chief Revenue Officer Sponsored by Cardlytics Mashable Preconference Session (4:00 p.m.) Roger Adams (Host) SPEAKING TO THE CONSUMER Senior Vice President, Chief Marketing Officer BRANDING IN A DIGITAL WORLD IN B-TO-B MARKETING USAA What does it take for brands to cut B-to-B Marketing used to be simple: Bob Liodice through the clutter? How do brands living up to its nickname of “Boring President and Chief Executive Officer truly engage with and win loyalty from to Boring,” it was formulaic and, full ANA consumers in the digital age? ANA’s of product facts and proof points. We Marketing2020 partner EffectiveBrands were forgetting that B-to-B buyers are TACO BELL: will share key learnings from the people first. Reaching through to the AD AGE MARKETER OF THE YEAR Marketing2020 study, and review a “consumer” in your target business framework for assessing, building, and audience may be the best way to influ- Taco Bell, named 2013 Ad Age embedding winning brand characteris- ence behavior. -

Shortlist (PR Lions)

Shortlist (PR Lions) Cat. No Entry No Title Client Product Entrant Company Country Agency Media Agency Production Company A01 (Food & Nutrition) A01/004 01188 THIS IS WHOLESOME HONEY MAID SNACKS DROGA5 New York USA DROGA5 New York / WEBER SHANDWICK JEFFERSON Los Angeles / Chicago, IL BRAINWASH FILMS Santa Monica A01/014 01000 ALMOST IDENTICAL MONDELEZ INTERNATIONAL BELDENT INFINIT DEL CAMPO SAATCHI & ARGENTINA DEL CAMPO SAATCHI & SAATCHI Buenos Aires AGOSTO BUENOS AIRES SAATCHI Buenos Aires A01/017 00905 OREO TRENDING VENDING MONDELEZ INTERNATIONAL OREO RUDER FINN New York USA RUDER FINN New York TONGAL Los Angeles A02 (Automotive and Transport) A02/002 01175 KOMBI LAST WISHES VOLKSWAGEN DO BRASIL VOLKSWAGEN BUS ALMAPBBDO São Paulo BRAZIL ALMAPBBDO São Paulo SPRAY FILMES São Paulo A02/007 00467 DACIA SPONSOR DAY RENAULT ITALIA DACIA PUBLICIS CONSULTANTS ITALY PUBLICIS CONSULTANTS ITALIA Milan OMD Rome BEDESCHI FILM Milan ITALIA Milan A02/015 00026 THE CANADIAN TIRE ICE CANADIAN TIRE CORPORATION MOTOMASTER CANADIAN TIRE CANADA CANADIAN TIRE CORPORATION Toronto / NORTH TOUCHE! PHD Montréal NOTCH VIDEO Toronto TRUCK ELIMINATOR BATTERY CORPORATION Toronto STRATEGIC Toronto A02/023 00740 HARLEY-DAVIDSON GLOBAL HARLEY-DAVIDSON MOTOR HARLEY-DAVIDSON HARLEY-DAVIDSON EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM LEXIS London 110TH ANNIVERSARY COMPANY LTD London CELEBRATION A03 (Healthcare & Wellbeing) A03/009 01718 DAD'S PREGNANT TOO KIMBERLY CLARK HUGGIES OGILVY & MATHER ARGENTINA OGILVY & MATHER ARGENTINA Buenos Aires MINDSHARE Buenos Aires ORUGA CINE Buenos Aires ARGENTINA -

Shortlist (PR Lions)

Shortlist (PR Lions) Cat. No Entry No Title Client Product Entrant Company Country Agency Media Agency Production Company A01 (Food & Nutrition) A01/004 01188 THIS IS WHOLESOME HONEY MAID SNACKS DROGA5 New York USA DROGA5 New York / WEBER SHANDWICK JEFFERSON Los Angeles / Chicago, IL BRAINWASH FILMS Santa Monica A01/014 01000 ALMOST IDENTICAL MONDELEZ INTERNATIONAL BELDENT INFINIT DEL CAMPO SAATCHI & ARGENTINA DEL CAMPO SAATCHI & SAATCHI Buenos Aires AGOSTO BUENOS AIRES SAATCHI Buenos Aires A01/017 00905 OREO TRENDING VENDING MONDELEZ INTERNATIONAL OREO RUDER FINN New York USA RUDER FINN New York TONGAL Los Angeles A02 (Automotive and Transport) A02/002 01175 KOMBI LAST WISHES VOLKSWAGEN DO BRASIL VOLKSWAGEN BUS ALMAPBBDO São Paulo BRAZIL ALMAPBBDO São Paulo SPRAY FILMES São Paulo A02/007 00467 DACIA SPONSOR DAY RENAULT ITALIA DACIA PUBLICIS CONSULTANTS ITALY PUBLICIS CONSULTANTS ITALIA Milan OMD Rome BEDESCHI FILM Milan ITALIA Milan A02/015 00026 THE CANADIAN TIRE ICE CANADIAN TIRE CORPORATION MOTOMASTER CANADIAN TIRE CANADA CANADIAN TIRE CORPORATION Toronto / NORTH TOUCHE! PHD Montréal NOTCH VIDEO Toronto TRUCK ELIMINATOR BATTERY CORPORATION Toronto STRATEGIC Toronto A02/023 00740 HARLEY-DAVIDSON GLOBAL HARLEY-DAVIDSON MOTOR HARLEY-DAVIDSON HARLEY-DAVIDSON EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM LEXIS London 110TH ANNIVERSARY COMPANY LTD London CELEBRATION A03 (Healthcare & Wellbeing) A03/009 01718 DAD'S PREGNANT TOO KIMBERLY CLARK HUGGIES OGILVY & MATHER ARGENTINA OGILVY & MATHER ARGENTINA Buenos Aires MINDSHARE Buenos Aires ORUGA CINE Buenos Aires ARGENTINA -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field. Original Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field / Monaci, Sara. - In: WESTMINSTER PAPERS IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE. - ISSN 1744-6716. - ELETTRONICO. - 11(1)(2016), pp. 49-64. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2656317 since: 2016-11-18T14:44:35Z Publisher: Westminster University Press Published DOI:10.16997/wpcc.218 Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 29 September 2021 Monaci, S. (2016). Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 11(1), 49–64, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.218 RESEARCH ARTICLE Boosting Creativity through Digital Disruption? The Role of Co-Creation Platforms in the Media Production Field Sara Monaci Politecnico di Torino, Italy [email protected] Web technologies transformed the media production field in many aspects: audio- visual contents in particular, are at the centre of a reshaping process involv- ing their use, creative production, distribution and consumption. The effects of digital disruption are revealed though a media production field characterized by an increasing complexity. Co-creation environments emerge as new digital inter- mediaries, which may integrate the open collaboration of peers with the need to identify new ways of recognising and enhancing creativity in a sustainable way.