Million Dollar Quartet” by Colin Escott & Floyd Mutrux at the Hippodrome Theatre Through December 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHOOL BOARD MEETING May 20, 2014 5:00 P.M. School

Lynchburg City Schools 915 Court Street Lynchburg, Virginia 24504 Lynchburg City School Board SCHOOL BOARD MEETING May 20, 2014 5:00 p.m. Regina T. Dolan-Sewell School Administration Building School Board District 1 Board Room Mary Ann Hoss School Board District 1 A. CLOSED MEETING Michael J. Nilles School Board District 3 1. Notice of Closed Meeting Jennifer R. Poore Scott S. Brabrand. Page 1 School Board District 2 Discussion/Action Katie Snyder School Board District 3 2. Certification of Closed Meetng Scott S. Brabrand. Page 2 Treney L. Tweedy School Board District 3 Discussion/Action J. Marie Waller School Board District 2 B. PUBLIC COMMENTS Thomas H. Webb 1. Public Comments School Board District 2 Scott S. Brabrand. Page 3 Charles B. White Discussion/Action (30 Minutes) School Board District 1 C. SPECIAL PRESENTATION School Administration Scott S. Brabrand 1. Student Recognitions Superintendent Scott S. Brabrand. Page 4 Discussion William A. Coleman, Jr. Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction 2. LCS: Why We Stand Out Ben W. Copeland Scott S. Brabrand. Page 5 Assistant Superintendent of Discussion Operations and Administration Anthony E. Beckles, Sr. D. FINANCE REPORT Chief Financial Officer Wendie L. Sullivan 1. Finance Report Clerk Anthony E. Beckles, Sr. .Page 6 Discussion E. CONSENT AGENDA 1. School Board Meeting Minutes: May 6, 2014 (Regular Meeting) F. STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE COMMENTS G. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 1. Carl Perkins Funds: 2014-15 William A. Coleman, Jr. Page 11 Discussion/Action 2. School Board Retreat Scott S. Brabrand. Page 14 Discussion/Action 3. Update Extra-Curricular Supplements and Stipends Ben W. -

HOW GREAT THOU ART: the GOSPEL of ELVIS PRESLEY PASSENGER INFORMATION (1St Traveler) PASSENGER INFORMATION (2Nd Traveler)

HOW GREAT THOU ART: THE GOSPEOLc toOberF 14 ,E 20L2V1 IS PRESLEY (Please fill out and return with payment to secure your spot) HOW GREAT THOU ART: THE GOSPEL OF ELVIS PRESLEY PASSENGER INFORMATION (1st Traveler) PASSENGER INFORMATION (2nd Traveler) First Name: First Name: Last Name(s): Last Name(s): Phone: (h) (c) Phone: (h) (c) Email: Email: CREDIT CARD PAYMENTS (tour cost subject to 3% credit card transaction fee): Tour Cost *: $135 per person (Please Note: The charge will appear on your statement as Windstar Lines) *Tour cost subject to 3% credit card transaction fee. Visa Mastercard In the amount of: Full payment is required with your registration form in order to hold your spot. Credit Card Number: REGISTRATION CLOSES: AUGUST 10, 2021 Exp. Date: / Security Code: month / year DEPOSIT PAYMENT INFORMATION: Name as it appears on card: Enclosed is my check, made payable to: Star Destinations In the amount of: Mail Check to: Star Destinations P.O. Box 456, Carroll, IA 51401 Tour requires a minimum of 25 passengers to operate. PLEASE TURN OVER FOR SIGNATURE DAY 1 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 14 ROCK ISLAND, IL (Lunch) We’ll board our motorcoach this morning and relax on the drive to the Circa ‘21 Dinner INCLUSIONS Playhouse for lunch and a performance of How Great Thou Art: The Gospel of Elvis Presley Deluxe Motorcoach Transportation From starring Robert Shaw and The Lonely Street Band! From the earliest days of his boyhood until his Cedar Rapids/Iowa City untimely death, gospel music always held a special place in the heart of Elvis Presley. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

SUN STUDIO Inspelningsteknik Och Sound

Högskoleexamen SUN STUDIO Inspelningsteknik och sound Författare: Jacob Montén Handledare: Karin Eriksson Examinator: Karin Larsson Eriksson Termin: HT 2019 Ämne: Musikvetenskap Nivå: Högskoleexamen Kurskod: 1MV706 Abstrakt Detta är en uppsats som handlar om Sun Studio under 1950 talet i USA, hur studion kom till och om dess grundare Sam Phillips och de tekniska tillgångarna och begränsningar som skapade ”soundet” för Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ike Turner och många fler. Sam Phillips producerade många tidlösa inspelningar med ljudkaraktäristiska egenskaper som eftertraktas än idag. Med hjälp av litteratur-, ljud- och bildanalys beskriver jag hur musikern och producenten bakom musiken skapade det så kallade ”Sun Soundet”. Ett uppvaknande i musikvärlden för den afroamerikanska musiken hade skett och ingen skulle få hindra Phillips från att göra den hörd. För att besvara mina frågeställningar har texter, tidigare forskning och videomaterial analyserats. Genom den hermeneutiska metoden har intervjumaterial och dokumentärer varit en viktig källa i denna studie. Nyckelord Sun Records, Sam Phillips, Slapback Echo, Soundet, Sun Studio, Analog Tack Stort tack till min handledare Karin Eriksson för den feedback och stöd jag har fått under arbetets gång. Tack till min familj för er uppmuntran och tålamod. Innehållsförteckning Innehållsförteckning.................................................................................................................1 1.Inledning...............................................................................................................................2 -

Pobierz Ten Artykuł Jako

�������������������������� pop/rock Jerry Lee Lewis Gordon Haskell Hionides The Black Crowes Mean Old Man One Day Soon Croweology Verve 2010 Gordon Haskell Hionides 2010 Silver Arrow Records 2010 Dystrybucja: Universal Music Polska Muzyka: §§§§¨ Muzyka: §§§§§ Muzyka: §§§§§§ Realizacja: §§§§¨ Realizacja: §§§§¨ Realizacja: §§§§¨ Już cztery lata temu Jerry Lee Lewis Na początek trzy mocne punkty. Utwór Album kolejnego wykonawcy sięga- doczekał się dowodu uznania od kolegów otwierający płytę jest godnym następ- jącego w przeszłość, chociaż nie aż tak z branży w postaci albumu „Last Man cą „Harry’s Bar” – hitu, który kilka lat odległą jak ta, do której ostatnio wracają Standing”. Towarzyszyli mu na nim m.in. temu odnowił zainteresowanie słucha- Phil Collins czy Eric Clapton. Grupa ( e Jimmy Page, B.B. King, Bruce Spring- czy angielskim wykonawcą, szczycą- Black Crowes, znana przede wszystkim steen i Neil Young. Płyta okazała się suk- cym się krótką współpracą z zespołem z „Shake Your Money Maker” (1990), cesem, więc Lewis powrócił do koncepcji King Crimson. Piosenki „( e Fools of z okazji 20-lecia ukazania się ich debiu- nagrań z udziałem sław. Yesterday” nie powstydziliby się najlepsi tanckiej płyty, nagrała jeszcze raz swoje Może lista gości na „Mean Old Man” rockmani. Choć należy dodać, że solowe najpopularniejsze piosenki – tym razem jest mniej spektakularna, ale i tak robi dokonania autora „One Day Soon” nie w wersjach akustycznych – i wydała je na wrażenie. Jak na poprzednim krążku mają prawie nic wspólnego z nagraniami podwójnym albumie „Croweology”. usłyszymy tu trzech Stonesów, Erica grupy kierowanej przez Roberta Frippa. Co mamy w efekcie? Kolejny zbiór nie- Claptona i Ringo Starra. Nowi goście to: Gordon Haskell słynie bowiem z melo- co inaczej brzmiących hitów? Ależ skąd! Sheryl Crow, Slash czy John Mayer. -

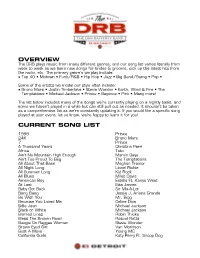

DRB Master Song List.Pages

OVERVIEW The DRB plays music from many different genres, and our song list varies literally from week to week as we learn new songs for brides & grooms, pick up the latest hits from the radio, etc. The primary genre’s we play include: • Top 40 • Motown • Funk/R&B • Hip Hop • Jazz • Big Band/Swing • Pop • Some of the artists we model our style after include: • Bruno Mars • Justin Timberlake • Stevie Wonder • Earth, Wind & Fire • The Temptations • Michael Jackson • Prince • Beyonce • Pink • Many more! The list below includes many of the songs we’re currently playing on a nightly basis, and some we haven’t played in a while but can still pull out as needed. It shouldn’t be taken as a comprehensive list as we’re constantly updating it. If you would like a specific song played at your event, let us know, we’re happy to learn it for you! CURRENT SONG LIST 1999 Prince 24K Bruno Mars 7 Prince A Thousand Years Christina Perri Africa Toto Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Summer Long Kid Rock All Blues Miles Davis American Boy Estelle Ft. Kanye West At Last Etta James Baby Got Back Sir Mix-A-Lot Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande Be With You Mr. Bigg Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Billie Jean Michael Jackson Black or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bust A Move Young MC California Gurls Katy Perry Ft. -

ELVIS PRESLEY BIOGRAPHY and Life in Pictures Compiled by Theresea Hughes

ELVIS PRESLEY FOREVER ELVIS PRESLEY FOREVER ELVIS PRESLEY FOREVER ELVIS PRESLEY BIOGRAPHY and life in pictures compiled by Theresea Hughes. Sample of site contents of http://elvis-presley-forever.com released in e-book format for your entertainment. All rights reserved. (r.r.p. $27.75) distributed free of charge – not to be sold. 1 Chapter 1 – Elvis Presley Childhood & Family Background Chapter 2 – Elvis’s Early Fame Chapter 3 – Becoming the King of Rock & Roll Chapter 4 – Elvis Presley Band Members http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-band-members.html Chapter 5 – Elvis Presley Girlfriends & Loves http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-girlfriends.html Chapter 6 – Elvis Presley Memphis Mafia http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-memphis-mafia.html Chapter 7 – Elvis Presley Spirit lives on… http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-spirit.html Chapter 8 – Elvis Presley Diary – Calendar of his life milestones http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-diary.html Chapter 9 – Elvis Presley Music & Directory of songs & Lyrics http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-music.html Chapter 10 – Elvis Presley Movies directory & lists http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-biography-elvis-presley-movies.html Chapter 11 – Elvis Presley Pictures & Posters http://elvis-presley-forever.com/elvis-presley-pictures-poster-shop.html Elvis Presley Famous Quotes by -

Jay Richardson Brushes Away Snow That's Drifted Around

When popular Beaumont deejay J.P. Richardson died on Feb. 3, 1959, with Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens, he left behind more than ‘Chantilly Lace’ … he left a briefcase of songs never sung, a widow, a daughter and unborn son, and a vision of a brave new rock world By RON FRANSCELL Feb. 3, 2005 CLEAR LAKE, IOWA –Jay Richardson brushes away snow that’s drifted around the corpse-cold granite monument outside the Surf ballroom, the last place his dead father ever sang a song. Four words are uncovered: Their music lives on. But it’s just a headstone homily in this place where they say the music died. A sharp wind slices off the lake under a steel-gray sky. It’s the dead of winter and almost nothing looks alive here. The ballroom – a rock ‘n’ roll shrine that might not even exist today except for three tragic deaths – is locked up for the weekend. Skeletal trees reach their bony fingers toward a low and frozen quilt of clouds. A tattered flag’s halyard thunks against its cold, hollow pole like a broken church bell. And not a word is spoken. Richardson bows his head, as if to pray. This is a holy place to him. “I wish I hadn’t done that,” he says after a moment. Is he still haunted by the plane crash that killed a father he never knew? Can a memory be a memory if it’s only a dream? Why does it hurt him to touch this stone? “Cuz now my damn hand is cold,” Richardson says, smiling against the wind. -

Sam Phillips: Producing the Sounds of a Changing South Overview

SAM PHILLIPS: PRODUCING THE SOUNDS OF A CHANGING SOUTH OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did the recordings Sam Phillips produced at Sun Records, including Elvis Presley’s early work, reflect trends of urbanization and integration in the 1950s American South? OVERVIEW As the U.S. recording industry grew in the first half of the 20th century, so too did the roles of those involved in producing recordings. A “producer” became one or more of many things: talent scout, studio owner, record label owner, repertoire selector, sound engineer, arranger, coach and more. Throughout the 1950s, producer Sam Phillips embodied several of these roles, choosing which artists to record at his Memphis studio and often helping select the material they would play. Phillips released some of the recordings on his Sun Records label, and sold other recordings to labels such as Chess in Chicago. Though Memphis was segregated in the 1950s, Phillips’ studio was not. He was enamored with black music and, as he states in Soundbreaking Episode One, wished to work specifically with black musicians. Phillips attributed his attitude, which was progressive for the time, to his parents’ strong feelings about the need for racial equality and the years he spent working alongside African Americans at a North Alabama farm. Phillips quickly established his studio as a hub of Southern African-American Blues, recording and producing albums for artists such as Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King and releasing what many consider the first ever Rock and Roll single, “Rocket 88” by Jackie Breston and His Delta Cats. But Phillips was aware of the obstacles African-American artists of the 1950’s faced; regardless of his enthusiasm for their music, he knew those recordings would likely never “crossover” and be heard or bought by most white listeners. -

What the Experts Say About Mississippi Music

What The Experts Say Blues in Mississippi *Alan Lomax in his book , The Land Where the Blues Began, said, AAlthough this has been called the age of anxiety, it might better be termed the century of the blues, after the moody song style that was born sometime around 1900 in the Mississippi Delta.@ Lomax goes on to credit black Delta blues musicians by saying, ATheir productions transfixed audiences; and white performers rushed to imitate and parody them in the minstrel show, buck dancing, ragtime, jazz, as nowadays in rock, rap, and the blues.@ *While there was indeed anxiety between blacks and whites in Mississippi, at least one venue demanded mutual respect - - - - music. Robert M. Baker, author of A Brief History of the Blues, said, A...blues is a native American musical and verse form, with no direct European and African antecedents of which we know. In other words, it is a blending of both traditions.@ However, there is no question that rhythmic dance tunes brought over by slaves influenced greatly the development of the blues. Blacks took the instruments and church music from Europe and wove them with their ancestral rhythms into what we know as the blues. *Christine Wilson, in the Mississippi Department of Archives publication, All Shook Up, Mississippi Roots of American Popular Music, said, A Music that emerged from Mississippi has shaped the development of popular music of the country and world. Major innovators created new music in every form - - - gospel, blues, country, R&B, rock, and jazz.@ *William Farris in Blues From the Delta wrote, ABlues shape both popular and folk music in American culture; and blues-yodeling Jimmie Rodgers, Elvis Presley, and the Rolling Stones are among many white performers who incorporate blues in their singing styles.@ For another example, Joachim Berendt=s book, The Jazz Book, outlines the development of jazz from its blues roots. -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

Behind the Gear Studios and I Worked There for Three Weeks

brothers - I’d had enough. So then I went to A&M Behind The Gear Studios and I worked there for three weeks. The studio This Issue’s Guru of Gadgets sucked then. There was sort of a bad, lean-on-the- by Larry Crane shovel attitude. I felt like everyone there was just collecting paychecks - I like to work. So I went to the Jonathan Little Village Recorders, which is a nice studio. It was owned by Geordie Hormel. I worked there from 1984 to 1987. I’d gotten to know Jimmy Iovine and Shelly Yakus from the Cherokee days. They were working at Cherokee and we did the Tom Petty record Southern Accents and the Eurythmics [Be Yourself Tonight], one of those Talking Heads records [True Stories] with Eric Thorngren engineering, Robbie Robertson’s first [self-titled] solo record with Daniel Lanois and a lot of records with Gary Katz. Being a tech was nice because I didn’t have From the first moment another engineer Phase-Corrected Speaker Systems” (which later I put in to sit in the room all the time, but back then you were raved about a Little Labs DI to me, I knew the end of the IBP manual). I sent that out with my pretty involved in the whole process. I built my first that this company was onto something resume, saying, “This is some of my work.” Tom Lubin, mic pre while I was there. Tchad Blake and Mitchell special. It turns out Little Labs is the editor of RE/P Magazine, said to come see him in Froom really liked it.