2019 - 2021 EW Sparrow Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 New Physicians

munsonhealthcare.org more than 1,200 providers representing 76 specialties. 76 representing providers 1,200 than more with partners it network, health regional a As Michigan. northern in counties 30 from patients Munson Healthcare and affiliated hospitals serve serve hospitals affiliated and Healthcare Munson 2020 New Physicians New That network just got bigger. got just network That Michigan. lower northern in physicians of network largest the have We Sleep Medicine Ferris Alkazir, MD Hospital: Munson Medical Center Education: American University of Antigua Residency: Western Michigan University Fellowship: Detroit Medical Center/Wayne State University Joined: Munson Sleep Disorders Center Contact: 231-935-9307 Urology Diane B. Young, MD Hospital: Munson Medical Center Education: Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Shreveport Residency: University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences State University Joined: Bay Area Urology Contact: 231-935-0322 Vitreoretinal Surgery Nathan D. Farley, MD Hospital: Munson Medical Center Education: Wayne State University Residency: Henry Ford Hospital/Wayne State University Joined: Associated Retinal Consultants Contact: 231-938-0710 (P): Primary Hospital *Also reads for other hospitals in the Munson Healthcare system Anesthesiology Orthopaedic Surgery Trent J. Rook, MD Rebecca A. Hess, MD Thomas Walbridge, DO Daniel K. Wilcox, MD Hospital: Munson Medical Center Hospital: Munson Healthcare Cadillac Hospital: Munson Medical Center Hospital: Mackinac Straits Health System Education: Pennsylvania -

Summer Events Guide Project1 Layoutbe a 1Tourist 4/1/19 10:44 in AM Your Page 1 Own Town, Margarita Fest, Jazz Fest, Fireworks and More

A Newspaper for the rest of us • www.lansingcitypulse.com FREE May 29 - June 4, 2019 Summer Events Guide Project1_LayoutBe a 1Tourist 4/1/19 10:44 in AM Your Page 1 Own Town, Margarita Fest, Jazz Fest, fireworks and more ... See page 14 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • May 29, 2019 City Pulse • May 29, 2019 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 Favorite Things THE EDGE OF THINGS: Lansing artist ERI VK and her DISSIDENT ART UNDER mannequin coffee table REPRESSIVE REGIMES Join us for the opening reception of The Edge of Things: Dissident Art Under Repressive Regimes, an exhibtion of experimental artworks made by artists from Argentina, Brazil, and Chile in resistence to Regina Vater, Mulher Mutante (Mutant Woman), 1968. oppresive social and Courtesy Galeria Jaqueline Martins. political conditions. MAY 31, 6–8pm I was a manager at American lot because I am an artist and am Apparel, which is now gone. When always having fun with the space. the store was closing, we got all Sometimes it is a coffee table. these cool mannequins. These were Sometimes I stack it on top of up along the walls on the shelves. another thing to have fun with it. 1 They used to model men’s under- I also use this shelf at art shows to JUNE wear like briefs. I guess I could exhibit my stuff. , . dress briefs on them now. I haven’t I would eventually like to get into Y P.M A O 5 thought about that before. set design or prop styling like this. D . -

BRT Newsletter

CORRIDOR OF Capitol Ave Grand Ave Delta St Abbot Rd Charles St Cedar St/Larch St 8th St Sparrow Hospital Lathrop St Clemens Ave Foster Ave Detroit St Morgan Ln Cowley Ave Harrison Rd Collingwood Dr POSSIBILITIES 2015 Bogue St Stoddard Ave Hagadorn Rd Michigan Ave Brookfield Dr Grand River Ave Northwind Dr Campus Hill Dr Montrose Ave Okemos Rd Meridian Mall Rd MICHIGAN AVENUE/ GRAND RIVER AVENUE 1 2 3 4 5 PUBLIC HEARING AND REVIEW The public will be given an opportunity Journal and the City Pulse at least where the draft EA document can be FPO to ask questions, get answers and 30 days in advance of the hearing. reviewed. The draft will be available for comment on the draft EA document at Information will also be posted on the review and comment 15 days before (NEED HI-RES) an upcoming public hearing and during project website at www.cata-brt.org and 15 days after the public hearing, the review period. When the date of the and at www.cata.org. The notice will for a total of 30 days. hearing is set, a notice of availability include the date, time and location of will be published in the Lansing State the public hearing, as well as locations ILLUSTRATION OF PROPOSED STATION DESIGN. Stay abreast of BRT-related developments at CATA-BRT.ORG rideCATA @rideCATA PROJECT NEED PROJECT PURPOSE Crowded buses, busy sidewalks and traffic congestion are The purpose of the BRT is to address travel delays for indicative of the high travel demand within this corridor. -

Existing and Future Conditions Inventory

Michigan / Grand River Avenue Transportation Study TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM From: URS Consultant Team To: CATA Project Staff and Technical Committee Date: October 28, 2009 Topic: Technical Memorandum #2 – Existing/Future Conditions Inventory 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Existing/Future Conditions Inventory is the second in a series of technical memorandums for the Michigan/Grand River Avenue Transportation Corridor. This information will be referred to as part of the development and evaluation of alternatives and, ultimately the definition of a Locally Preferred Alternative for improving transit service and overall multimodal transportation service in the Michigan / Grand River Avenue Transportation Corridor (Map 1-1). This Technical Memorandum is divided into the following sections: Section 2 provides an inventory of the Corridor’s existing transportation network characteristics and conditions. Section 3 describes population and household trends impacting transportation in the Corridor. Section 4 gives an overview of existing employment clusters and projected trends for future job growth in the Region and Corridor. Section 5 provides a summary of the land uses and development trends in the Corridor. Section 6 gives an overview of cultural resource needs analysis in Region and Corridor. Section 7 provides a summary of natural environment concerns including floodplains, wetlands, 4(f) and 6(f) impacts, and groundwater Section 8 describes hazardous materials/waste site analysis needs in the Corridor Technical Memorandum #2: 10/28/2009 1 Existing/Future Conditions Analysis Michigan Ave/Grand River Ave Multimodal Corridor Studies Section 9 provides an overview of air quality analysis needs and the process to identify the regulatory framework for the Corridor air quality Section 10 discusses noise and vibration analysis needs within the Corridor 2.0 TRANSPORTATION CHARACTERISTICS Communities in the Michigan / Grand River Corridor are experiencing a host of transportation related problems and needs. -

REO Town Historic Survey

HISTORIC RESOURCE SURVEY REPORT R E O T O W N LANSING, INGHAM COUNTY, MICHIGAN Prepared for Michigan State Historic Preservation Office April 26th, 2019 Prepared by Joe Parks Emily Stanewich Zach Tecson Jacob Terrell Urban and Regional Planning Practicum School of Planning, Design and Construction Michigan State University REO Town, Lansing, Michigan Historic Resource Survey Report _____________________________________________________________________________________________ SECTION I Acknowledgements This project has been supported immensely by faculty and staff at Michigan State University and the City of Lansing. We would like to express our appreciation to our instructors, Lori Mullins and Patricia Machemer, for their valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this report. We also wish to acknowledge the assistance and guidance provided by the City of Lansing’s Economic Development and Planning Office and Historic District Commission through Bill Rieske and Cassandra Nelson. The contents and opinions herein do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of Michigan State University or the City of Lansing, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products herein constitute endorsement or recommendation by Michigan State University or the City of Lansing. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 REO Town, Lansing, Michigan Historic Resource Survey Report _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Executive Summary This Historic Resource Survey Report on REO Town, Lansing was commissioned by the City of Lansing. The scope of this project includes three main components: collect physical and historical data for each building within the proposed REO Town Historic District, compose a final survey report that includes an intensive level survey analysis, and create an excel database with detailed property information. -

Agenda 1301 S

Potter Park Zoo Advisory Board AGENDA 1301 S. Pennsylvania Avenue ~ Lansing, MI 48912 Telephone: 517.342.2776; Fax: 517.316.3894 The Board information packet is available on-line by going to www.ingham.org, selecting “Monthly Calendar,” and clicking on “Wednesday, June 10, 2020”. POTTER PARK ZOO ADVISORY BOARD MEETING Wednesday, June 10, 2020 6:00 PM Via Zoom 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of May 13, 2020 Meeting Minutes. 3. Limited Public Comment – Limited to 3 minutes with no discussion 4. Late Items/Deletions/Consent Items 5. Director’s Report a. May 2020 Finance Report – Delphine Breeze b. Director’s Report – Cynthia Wagner/Amy Morris 6. New Business a. Resolution – Ingham County Parks and Zoo Rules b. 2021 Budget Discussion 7. Old Business a. Zoo Reopening Plan b. Strategy Subcommittee – Mary Leys c. External Relations Subcommittee – Cheryl Bergman d. Financial Sustainability Subcommittee – Kyle Binkley 8. Board Comments 9. Limited Public Comment - Limited to 3 minutes with no discussion 10. Upcoming Meeting a. Zoo Advisory Board Meeting July 8, 2020 at 6:00 PM 11. Adjournment Official minutes are stored and available for inspection at the address noted at the top of this agenda. Potter Park Zoo will provide necessary reasonable auxiliary aids and services, such as interpreters for the hearing impaired and audio tapes of printed materials being considered at the meeting for the visually impaired, for individuals with disabilities at the meeting upon five (5) working days’ notice to the Zoo. Individuals with disabilities requiring auxiliary aids or services should contact the Zoo by writing to: Zoo Director, 1301 S. -

Celebrating 15 Years

Celebrating 15 years “The number of properties, projects and people that have been ‘touched’ and transformed into viable outcomes and striking successes is a testament to the concentrated efforts of the Land Bank and the partners we work with.” – Roxanne Case, Executive Director, Ingham County Land Bank STRENGTHENING THE REGION In 2005, the Ingham County Land Bank was the second county land bank established in Michigan—now more than half of Michigan counties have a land bank. 15 years later, we are proud of the accomplishments we’ve made. BEFORE AFTER Invested $58,000,000 through federal, state and local funds Renovated 255 single-family homes Constructed 42 new Established nearly Completed nearly single-family homes 200 garden parcels 800 demolitions Sold over 20 commercial Sold over Created a pipeline of over properties for redevelopment 500 vacant lots 200 properties sold to nonprofits and investors for development and/or renovations “The Ingham County Land Bank has had a tremendous impact on the revitalization of our neighborhood over the last 15 years. The Land Bank has chosen several strategically-located, tax-foreclosed houses to renovate and this has improved the overall appearance of many areas. This has helped to boost property values and helped this area to be a more functional place to be proud of. Houses that would not sell 15 years ago are now being sold and the neighborhood continues to improve.” – Dale Schrader, Walnut Neighborhood Organization CREATING BETTER COMMUNITIES Building great places one small step at a time… -

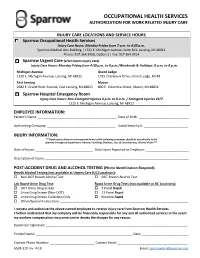

Sparrow Occupational Health Services Authorization for Work

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH SERVICES AUTHORIZATION FOR WORK RELATED INJURY CARE INJURY CARE LOCATIONS AND SERVICE HOURS Sparrow Occupational Health Services Injury Care Hours: Monday-Friday from 7 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Sparrow Medical Arts Building | 1322 E. Michigan Avenue, Suite 101, Lansing, MI 48912 Phone: 517.364.3900, Option 1 | Fax: 517.364.3914 Sparrow Urgent Care (after-hours injury care) Injury Care Hours: Monday-Friday from 4:30 p.m. to 8 p.m./Weekends & Holidays: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Michigan Avenue Grand Ledge 1120 E. Michigan Avenue, Lansing, MI 48912 1015 Charlevoix Drive, Grand Ledge, MI 48 East Lansing Mason 2682 E. Grand River Avenue, East Lansing, MI 48823 800 E. Columbia Street, Mason, MI 48854 Sparrow Hospital Emergency Room Injury Care Hours: Non-Emergent Injuries 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. / Emergent Injuries 24/7 1215 E. Michigan Avenue, Lansing, MI 48912 EMPLOYEE INFORMATION: Patient’s Name: ____________________________________________ Date of Birth: ____________________________ Authorizing Company: ______________________________________ Social Security #: _________________________ INJURY INFORMATION: ***Head Injuries that are accompanied by any of the following symptoms should be sent directly to the Sparrow Emergency Department: Nausea, Vomiting, Dizziness, Loss of Consciousness, Blurred Vision*** Date of Injury: ________________________________ Date Injury Reported to Employer: ________________________ Description of Injury: ________________________________________________________________________________ POST-ACCIDENT DRUG AND ALCOHOL -

Special Sparrow Michigan Athletic Club

elcome and thank you for joining us today for the 21st Anniversary of the Capital Area Health Alliance. The Alliance was incorporated in 1993 as a coalition of organizations, Wbusinesses, health care professionals, and volunteers from Clinton, Eaton, and Ingham counties to facilitate improvements in healthy living, access, quality, and cost, in health resources in the tri-county area. This year, the work of the Alliance has enabled accomplishments such as: The Capital Area Community Nursing Network’s celebration of Nurses Week with a continuing education program. This committee has highlighted nursing practice and workforce issues and expanded available nursing teaching and learning opportunities. The Capital Area Physician Experience (CAPE) sponsored its 6th “Dine Around” to introduce MSU medical students to local physicians to enhance recruitment and retention of physicians. In spring of 2015, CAPE will offer a speaker panel on regional activities to recruit physicians. The End-of-Life Care Committee has been addressing issues associated with best practices and opportunities for interdisciplinary integration for end-of-life issues and is planning a symposium for spring 2015. The Healthy Lifestyles Committee (HLC) was renewed for funding for the 2015 Michigan Health and Wellness 4 x 4 Grant. Through the 4 x 4 grant, the HLC is working to increase access to physical activity opportunities, work with local restaurants to highlight healthy menu items, and engage worksites to adopt new policies related to health and wellness. The Mental Health Partnership Council worked to advocate for availability and equality for mental health patients. This year, hundreds of people attended presentations dealing with numerous mental health issues. -

AGENDA Tuesday, January 16, 2018 5:30Pm PARKS & RECREATION

Ingham County Parks & Recreation Commission 121 E. Maple Street, P.O. Box 178, Mason, MI 48854 AGENDA Telephone: 517.676.2233; Fax: 517.244.7190 The packet is available on-line by going to www.ingham.org, choosing the “Monthly Calendar,” and clicking on Tuesday, January 16, 2018 Tuesday, January 16, 2018 5:30pm PARKS & RECREATION COMMISSION MEETING Main Shelter Lake Lansing Park North 6260 E. Lake Drive Haslett, Michigan 1. Call to Order 2. Pledge of Allegiance Note due to Holiday 3. Approval of Minutes meeting will be held on Minutes of December 11, 2017 regular meeting will be considered-Page 3 3 Tuesday instead of 4. Limited Public Comment ~ Limited to 3 minutes with no discussion Monday 5. APPROVE THE AGENDA Late Items / Changes/ Deletions 6. Check Presentation – Meridian Township Donation to the Friends of Ingham County Parks for the Lake Lansing Bandshell - Page 16 7. ELECTION OF 2018 OFFICERS A. Chair, Park Commission B. Vice-Chair, Park Commission C. Secretary, Park Commission 8. ADMINISTRATIVE REPORTS A. Director - Page 19 B. Park Managers - Page 20 C. Administrative Office - Page 24 D. Millage Coordinator Report - Page 26 E. FLRT Trail Ambassador Report - Lauren Ross - Page 27 9. ACTION ITEMS A. Resolution to Comply with Provisions of the Open Meetings Act Setting Parks & Recreation Commission Meetings for January 2018 through December 2018 - Page 28 B. Resolution Honoring Shirley Rodgers - Page 31 C. Master Plan Action Program Items – Page 32 D. Motion to Amend Recommendation for Funding for the Lansing Bank Stabilization-Washington Avenue Application - Page 46 10. DISCUSSION ITEMS A. -

5-Year Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021

Charter Township of Meridian Department of Parks and Recreation Creating Community through People, Parks, and Programs 5-Year Parks & Recreation Master Plan 2017-2021 Adopted February 2017 Meridian Township Parks and Recreation Master Plan 1 Park Commission 2017-2021 Michael McDonald, Acting Chair Mark Stephens, Commissioner Richard Baker, Commissioner Amanda Lick, Commissioner Annika Brixie Schaetzl, Commissioner Parks and Recreation Staff LuAnn Maisner, Parks & Recreation Director Robin Faust, Administrative Assistant II Jane Greenway, Senior Parks and Land Management Coordinator Mike Devlin, Parks & Recreation Specialist Darcie Weigand, Parks & Recreation Specialist Kit Rich, Senior Park Naturalist, Harris Nature Center Kati Adams, Senior Park Naturalist, Harris Nature Center Kelsey Dillon, Stewardship Coordinator Dennis Antone, Facilities Superintendent Cheri Wisdom, Senior Center Coordinator Department of Parks and Recreation Meridian Township Parks and Recreation Master Plan 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction 8 I . Community Description 16 A. Location Description and Population Information 16 Map A: Location Map 18 B. Meridian Township Residents 19 C. Summary of The National Citizen Survey 2015 19 D. Township Millages & Ordinances 19 II. Administrative Structure 21 A. Role of the Township Board 21 B. Role of Park Commission 21 C. Role of Land Preservation Advisory Board 21 D. Role of Parks and Recreation Department 22 E. Parks and Recreation Administrative Staff 23 F. Organizational Chart 28 G. Funding Sources and Budget 29 H. Role of Volunteers 31 I. Relationships with School Districts, Other Public Agencies and Private Organizations 34 J. Role of the Environmental Commission 35 K. Other Environmental Planning Organizations 35 L. Communications 35 III. Parks and Recreation Inventory and Evaluation 37 A. -

Michigan Regional Trauma Resources

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH Michigan Regional Trauma Resources Region 1 Report prepared by Theresa Jenkins RN, BSN Region 1 Trauma Coordinator August 2013 Contents Introduction to Region 1 ............................................................................................................................... 1 Injury……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………..………..…………..… 2-4 Regional Trauma System Infrastructure ....................................................................................................... 5 Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and Medical Control Authorities ..................................................... 5 Regional Trauma Coordinator .................................................................................................................. 6 Regional Trauma Network ........................................................................................................................ 6 Regional Trauma Advisory Committee ..................................................................................................... 7 Professional Standards Review Organization……………………………………………………………………………………….8 Governance .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Hospitals………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………….………………..…9 MDCH 2013 Trauma Needs Assessment …………………………………………………………………..………….………….10-14 Summary ....................................................................................................................................................