Desk Review: United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Capital Territory

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Imperial Acts Application Ordinance 1986 No. 93 of 1986 I, THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting with the advice of the Federal Executive Council, hereby make the following Ordinance under the Seat of Government (Administration) Act 1910. Dated 18 December 1986. N. M. STEPHEN Governor-General By His Excellency’s Command, LIONEL BOWEN Attorney-General An Ordinance relating to the application in the Territory of certain Acts of the United Kingdom Short title 1. This Ordinance may be cited as the Imperial Acts Application Ordinance 1986.1 Commencement 2. (1) Subject to this section, this Ordinance shall come into operation on the date on which notice of this Ordinance having been made is published in the Gazette. (2) Sub-section 4 (2) shall come into operation on such date as is fixed by the Minister of State for Territories by notice in Gazette. (3) Sub-section 4 (3) shall come into operation on such date as is fixed by the Minister of State for Territories by notice in the Gazette. Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au Imperial Acts Application No. 93 , 1986 2 Interpretation 3. (1) In this Ordinance, unless the contrary intention appears—“applied Imperial Act” means— (a) an Imperial Act that— (i) extended to the Territory as part of the law of the Territory of its own force immediately before 3 September 1939; and (ii) had not ceased so to extend to the Territory before the commencing date; and (b) an Imperial Act, other than an Imperial -

Crime (International Co-Operation) Act 2003

Source: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/32 Crime (International Co-operation) Act 2003 2003 CHAPTER 32 An Act to make provision for furthering co-operation with other countries in respect of criminal proceedings and investigations; to extend jurisdiction to deal with terrorist acts or threats outside the United Kingdom; to amend section 5 of the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981 and make corresponding provision in relation to Scotland; and for connected purposes. [30th October 2003] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— PART 1 MUTUAL ASSISTANCE IN CRIMINAL MATTERS CHAPTER 1 MUTUAL SERVICE OF PROCESS ETC. Service of overseas process in the UK 1Service of overseas process (1)The power conferred by subsection (3) is exercisable where the Secretary of State receives any process or other document to which this section applies from the government of, or other authority in, a country outside the United Kingdom, together with a request for the process or document to be served on a person in the United Kingdom. (2)This section applies— (a)to any process issued or made in that country for the purposes of criminal proceedings, (b)to any document issued or made by an administrative authority in that country in administrative proceedings, (c)to any process issued or made for the purposes of any proceedings on an appeal before a court in that country against a decision in administrative proceedings, (d)to any document issued or made by an authority in that country for the purposes of clemency proceedings. -

Fourteenth Report: Draft Statute Law Repeals Bill

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 211) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 140) STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor and the Lord Advocate by Command of Her Majesty April 1993 LONDON: HMSO E17.85 net Cm 2176 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the Law. The Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Brooke, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge, Q.C. Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon. Its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Lord Davidson, Chairman .. Dr E.M. Clive Professor P.N. Love, C.B.E. Sheriff I.D.Macphail, Q.C. Mr W.A. Nimmo Smith, Q.C. The Secretary of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr K.F. Barclay. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. .. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Mackay of Clashfern, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Q.C., Her Majesty's Advocate. In pursuance of section 3(l)(d) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, we have prepared the draft Bill which is Appendix 1 and recommend that effect be given to the proposals contained in it. -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission Working Paper No 62 Criminal Law Offences relating to the Administration of Justice LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 0 Crown copyright 7975 First published 7975 ISBN 0 11 730093 4 17-2 6-2 6 THE LAW COMMISSXON WORKING PAPER NO. 62 CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE CONTENTS Paras. I INTRODUCTION 1- 7 1 I1 PRESENT LAW 8- 25 5 Common Law 8- 17 5 Perverting the course of justice 8- 11 5 Examples of conspiracy charges 12- 13 8 Contempt of Court 14- 15 10 Escape and avoiding trial 16 11 Agreeing to indemnify bail 17 11 Statute ~aw 19- 25 12 Perjury 19- 20 12 Other statutory offences 21- 24 13 Summary 25 15 I11 PROPOSALS FOR REFORM 26-116 16 General 26- 33 16 Relationship with contempt of court 27- 29 17 Criminal and civil proceedings 30- 33 18 Outline of proposed offences 34- 37 20 1. Offences relating to all proceedings 38- 88 21 (i) Perjury 38- 60 21 iii Paras. Page Ihtroductory 38- 45 21 Should perjury be confined to false statements? 46 24 Oral evidence not on oath 47- 53 25 Extra-curial unsworn statements admissible as evidence 51- 59 28 Summary 60 31 (ii) Tampering with or fabricating evidence 61- 65 32 (iii)Preventing the attendance of witnesses 66- 67 34 (iv) Intimidation of a party 68- 84 35 (v) Improperly influencing a court 85- 91 43 2. Offences relating only to criminal matters 92-107 45 (i) Impeding the investigation of crime 93-101 45 (ii) Avoiding trial 102-105 50 (iii)Agreeing to indemnify bail 106-110 52 3. -

Get Licensed Contents

SIA licensing criteria January 2021 Get Licensed Contents Getting a Licence 5 Training and Qualifications 9 Criminal Records Checks 21 Relevant Offences for all Applicants 37 Refusing a Licence 41 Notifying Applicants of the SIA’s Conclusions 45 Conditions of a Licence 47 Revoking a Licence 51 Suspending a Licence 54 Annex A: List of relevant offences for all Applicants 57 SIA | Get Licensed January 2021 Introduction The Security Industry Authority (SIA) is the public body that regulates the private security industry in the United Kingdom. The Private Security Industry Act 2001 (“the Act”) established the SIA and sets out how regulation of the private security industry works. Section 3 of the Act makes it a criminal offence for individuals to engage in licensable conduct unless they have a licence. The SIA is responsible for granting, renewing and revoking these licences. Applicants and Licence Holders The people who are applying for licences whether someone can or cannot be are referred to as “Applicants” in this lawfully employed in regulated activities. document. They are called Applicants However, the SIA is not Applicants’ and even if they have had a licence in the Licence Holders’ employer. past and are applying for this licence to be renewed. The people who have active licenses are called “Licence Holders” even if they do not have a Criteria security job at the moment. The SIA uses rules called “criteria” to decide whether or not to grant a The relationship that Applicants and licence. Criteria are also used when the Licence Holders have with the SIA is a SIA applies its powers under the Act to relationship with a regulatory body. -

Perjury Act 1911

Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Perjury Act 1911. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) Perjury Act 1911 1911 CHAPTER 6 1 and 2 Geo 5 An Act to consolidate and simplify the Law relating to Perjury and kindred offences. [29th June 1911] Annotations: Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act amended by Criminal Justice Act 1967 (c. 80), s. 89(2) C2 Reference to penal servitude to be construed as reference to imprisonment: Criminal Justice Act 1948 (c. 58), s. 1(1) C3 Act amended as to mode of trial as to all offences (except offences under ss. 1, 3, 4) by Magistrates' Courts Act 1980 (c. 43), s. 106(2) 1 Perjury. (1) If any person lawfully sworn as a witness or as an interpreter in a judicial proceeding wilfully makes a statement material in that proceeding, which he knows to be false or does not believe to be true, he shall be guilty of perjury, and shall, on conviction thereof on indictment, be liable to penal servitude for a term not exceeding seven years, or to imprisonment . F1 for a term not exceeding two years, or to a fine or to both such penal servitude or imprisonment and fine. (2) The expression “judicial proceeding” includes a proceeding before any court, tribunal, or person having by law power to hear, receive, and examine evidence on oath. (3) Where a statement made for the purposes of a judicial proceeding is not made before the tribunal itself, but is made on oath before a person authorised by law to administer an oath to the person who makes the statement, and to record or authenticate the statement, it shall, for the purposes of this section, be treated as having been made in a judicial proceeding. -

Criminal Law

The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 96) CRIMINAL LAW OFFENCES RELATING TO INTERFERENCE WITH THE COURSE OF JUSTICE Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to heprinted 7th November 1979 LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 213 24.50 net k The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Kerr, Chairman. Mr. Stephen M. Cretney. Mr. Stephen Edell. Mr. W. A. B. Forbes, Q.C. Dr. Peter M. North. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr. J. C. R. Fieldsend and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION .......... 1.1-1.9 1 PART 11: PERJURY A . PRESENT LAW AND WORKING PAPER PROPOSALS ............. 2.1-2.7 4 1. Thelaw .............. 2.1-2.3 4 2 . The incidence of offences under the Perjury Act 1911 .............. 2.4-2.5 5 3. Working paper proposals ........ 2.6-2.7 7 B . RECOMMENDATIONS AS TO PERJURY IN JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS ........ 2.8-2.93 8 1. The problem of false evidence not given on oath and the meaning of “judicial proceedings” ............ 2.8-2.43 8 (a) Working paperproposals ...... 2.9-2.10 8 (b) The present law .......... 2.1 1-2.25 10 (i) The Evidence Act 1851. section 16 2.12-2.16 10 (ii) Express statutory powers of tribunals ......... -

Magistrates' Courts Act 1980 (C

Changes to legislation: Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 01 October 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 1980 CHAPTER 43 PART I CRIMINAL JURISDICTION AND PROCEDURE Jurisdiction to issue process and deal with charges 1 Issue of summons to accused or warrant for his arrest. [F1(1) On an information being laid before a justice of the peace that a person has, or is suspected of having, committed an offence, the justice may issue— (a) a summons directed to that person requiring him to appear before a magistrates' court to answer the information, or (b) a warrant to arrest that person and bring him before a magistrates' court.] (2) F2. (3) No warrant shall be issued under this section unless the information is in writing F3. (4) No warrant shall be issued under this section for the arrest of any person who has attained [F4 the age of 18 years] unless— (a) the offence to which the warrant relates is an indictable offence or is punishable with imprisonment, or (b) the person’s address is not sufficiently established for a summons to be served on him. [F5(4A) Where a person who is not a [F6relevant prosecutor authorised to issue requisitions] lays an information before a justice of the peace in respect of an offence to which this subsection applies, no warrant shall be issued under this section without the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions. -

Report Double Jeopardy

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG REPORT DOUBLE JEOPARDY This report can be found on the Internet at: <http://www.hkreform.gov.hk> February 2012 The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong was established by the Executive Council in January 1980. The Commission considers for reform such aspects of the law as may be referred to it by the Secretary for Justice or the Chief Justice. The members of the Commission at present are: Chairman: Mr Wong Yan-lung, SC, JP, Secretary for Justice Members: The Hon Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma Mr Eamonn Moran, JP, Law Draftsman Mr John Budge, SBS, JP The Hon Mr Justice Patrick Chan, PJ Mrs Pamela Chan, BBS, JP Mr Anderson Chow, SC Mr Godfrey Lam, SC Ms Angela W Y Lee, BBS, JP Mrs Eleanor Ling, SBS, JP Mr Peter Rhodes Professor Michael Wilkinson The Secretary of the Commission is Mr Stuart M I Stoker and its offices are at: 20/F Harcourt House 39 Gloucester Road Wanchai Hong Kong Telephone: 2528 0472 Fax: 2865 2902 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.hkreform.gov.hk THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG REPORT DOUBLE JEOPARDY ________________________________ CONTENTS Chapter Page Preface 1 Terms of reference 3 The sub-committee 3 Public consultation 4 Layout of the report 4 Acknowledgements 4 1. The rule against double jeopardy 6 The rule against double jeopardy 6 The autrefois doctrine: the pleas of autrefois acquit and 7 autrefois convict Relevant statutory provisions and cases in Hong Kong 8 Prerequisites for a plea of autrefois acquit or autrefois convict 9 The same offence 10 At risk of conviction; a valid verdict 13 A final verdict 14 Stay of proceedings 16 Procedure for making an autrefois plea 20 Conviction or acquittal by a foreign court 21 2. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by [F3section 33 of the Magistrates’Courts Act 1980)]] and to attempts to committ any 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Perjury Act, 1911. [1 & 2 GEO

R Perjury Act, 1911. [1 & 2 GEO. 5. CH. 6.] ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1911. Section. 1. Perjury. 2. False statements on oath made otherwise than in a judicial proceeding. 3. False statements, &c. with reference to marriage. 4. False statements, &c. as to births or deaths. 5. False statutory declarations and other false statements without oath. 6. False declarations, &c. to obtain registration, &c. for carrying on a vocation. 7. Aiders, abettors, suborners, &c. 8. Venue. 9. Power to direct a prosecution for perjury. 10. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 11. Application of Vexatious Indictments Act, 1859. 12. Form of indictment. 13. Corroboration. 14. Proof of certain proceedings on which perjury is assigned. 15. Interpretation, &c. 16. Savings. 17. Repeals. 18. Extent. 19. Short title and commencement. SCHEDULE. 1 [1 & 2 GEO. 5.] Perjury Act, 1911. [CH. 6.] CHAPTER 6. An Act to consolidate and simplify the Law relating to A.D. 1911. Perjury and kindred offences. [29th June 191.1.] E it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and B with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows : 1.-(1) If any person lawfully swt°rn as a witness or as an Perjury. interpreter in a judicial proceeding wilfully makes a statement material in that proceeding, which he knows to be false or does not believe to be true, he shall be guilty of perjury, and shall, on conviction thereof on indictment, be liable to penal servitude for a term not exceeding seven years, or to imprisonment with or without hard labour for a term. -

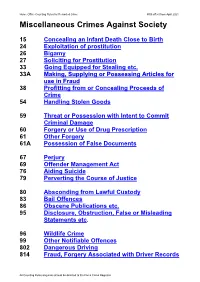

Counting Rules for Miscellaneous Crimes Against Society

Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 Miscellaneous Crimes Against Society 15 Concealing an Infant Death Close to Birth 24 Exploitation of prostitution 26 Bigamy 27 Soliciting for Prostitution 33 Going Equipped for Stealing etc. 33A Making, Supplying or Possessing Articles for use in Fraud 38 Profitting from or Concealing Proceeds of Crime 54 Handling Stolen Goods 59 Threat or Possession with Intent to Commit Criminal Damage 60 Forgery or Use of Drug Prescription 61 Other Forgery 61A Possession of False Documents 67 Perjury 69 Offender Management Act 76 Aiding Suicide 79 Perverting the Course of Justice 80 Absconding from Lawful Custody 83 Bail Offences 86 Obscene Publications etc. 95 Disclosure, Obstruction, False or Misleading Statements etc. 96 Wildlife Crime 99 Other Notifiable Offences 802 Dangerous Driving 814 Fraud, Forgery Associated with Driver Records All Counting Rules enquiries should be directed to the Force Crime Registrar Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime With effect from April 2021 15 Concealing an Infant Death Close to Birth (1 of 1) 15/00 Concealment of birth. (S) Offences against the Person Act 1861 Sec 60. General Rule: One crime for each child. Example 1: Twins are stillborn and the births are concealed. Two crimes (class 15). 24 Exploitation of Prostitution (1 of 1) For historic allegations committed under previous legislation, record and assign outcome as if committed today. 24/17 Causing or inciting prostitution for gain. 24/19 Keeping a brothel used for prostitution. (S/V) Sexual Offences Act 2003 Sec 52. (S) Sexual Offences Act 1956 Sec 33A (as added by Sexual Offences Act 2003 Sec 55).