Prioritization of Variants for Investigation of Genotype-Directed Nutrition in Human Superpopulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snps Related to Vitamin D and Breast Cancer Risk

Huss et al. Breast Cancer Research (2018) 20:1 DOI 10.1186/s13058-017-0925-3 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access SNPs related to vitamin D and breast cancer risk: a case-control study Linnea Huss1* , Salma Tunå Butt1, Peter Almgren 2, Signe Borgquist3,4, Jasmine Brandt1, Asta Försti5,6, Olle Melander2 and Jonas Manjer1 Abstract Background: It has been suggested that vitamin D might protect from breast cancer, although studies on levels of vitamin D in association with breast cancer have been inconsistent. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to be associated with vitamin D. The aim of this study was to investigate such vitamin D-SNP associations in relation to subsequent breast cancer risk. A first step included verification of these SNPs as determinants of vitamin D levels. Methods: The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study included 17,035 women in a prospective cohort. Genotyping was performed and was successful in 4058 nonrelated women from this cohort in which 865 were diagnosed with breast cancer. Levels of vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) were available for 700 of the breast cancer cases and 643 of unaffected control subjects. SNPs previously associated with vitamin D in GWASs were identified. Logistic regression analyses yielding ORs with 95% CIs were performed to investigate selected SNPs in relation to low levels of vitamin D (below median) as well as to the risk of breast cancer. Results: The majority of SNPs previously associated with levels of vitamin D showed a statistically significant association with circulating vitamin D levels. Heterozygotes of one SNP (rs12239582) were found to have a statistically significant association with a low risk of breast cancer (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68–0.99), and minor homozygotes of the same SNP were found to have a tendency towards a low risk of being in the group with low vitamin D levels (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52–1.00). -

Nicotinamide Riboside Kinases Display Redundancy in Mediating Nicotinamide Mononucleotide and Nicotinamide Riboside Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle Cells

Original Article Nicotinamide riboside kinases display redundancy in mediating nicotinamide mononucleotide and nicotinamide riboside metabolism in skeletal muscle cells Rachel S. Fletcher 1,2, Joanna Ratajczak 3,4, Craig L. Doig 1,2, Lucy A. Oakey 2, Rebecca Callingham 5, Gabriella Da Silva Xavier 5, Antje Garten 1,6, Yasir S. Elhassan 1,2, Philip Redpath 7, Marie E. Migaud 7, Andrew Philp 8, Charles Brenner 9, Carles Canto 3,4, Gareth G. Lavery 1,2,* ABSTRACT þ Objective: Augmenting nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD ) availability may protect skeletal muscle from age-related metabolic decline. þ Dietary supplementation of NAD precursors nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR) appear efficacious in elevating þ þ muscle NAD . Here we sought to identify the pathways skeletal muscle cells utilize to synthesize NAD from NMN and NR and provide insight into mechanisms of muscle metabolic homeostasis. þ Methods: We exploited expression profiling of muscle NAD biosynthetic pathways, single and double nicotinamide riboside kinase 1/2 (NRK1/ þ 2) loss-of-function mice, and pharmacological inhibition of muscle NAD recycling to evaluate NMN and NR utilization. Results: Skeletal muscle cells primarily rely on nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), NRK1, and NRK2 for salvage biosynthesis of þ þ NAD . NAMPT inhibition depletes muscle NAD availability and can be rescued by NR and NMN as the preferred precursors for elevating muscle þ cell NAD in a pathway that depends on NRK1 and NRK2. Nrk2 knockout mice develop normally and show subtle alterations to their NADþ metabolome and expression of related genes. NRK1, NRK2, and double KO myotubes revealed redundancy in the NRK dependent þ metabolism of NR to NAD . -

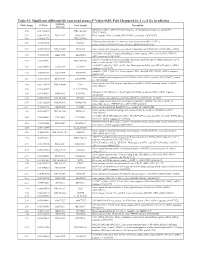

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Open Data for Differential Network Analysis in Glioma

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Open Data for Differential Network Analysis in Glioma , Claire Jean-Quartier * y , Fleur Jeanquartier y and Andreas Holzinger Holzinger Group HCI-KDD, Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation, Medical University Graz, Auenbruggerplatz 2/V, 8036 Graz, Austria; [email protected] (F.J.); [email protected] (A.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 27 October 2019; Accepted: 3 January 2020; Published: 15 January 2020 Abstract: The complexity of cancer diseases demands bioinformatic techniques and translational research based on big data and personalized medicine. Open data enables researchers to accelerate cancer studies, save resources and foster collaboration. Several tools and programming approaches are available for analyzing data, including annotation, clustering, comparison and extrapolation, merging, enrichment, functional association and statistics. We exploit openly available data via cancer gene expression analysis, we apply refinement as well as enrichment analysis via gene ontology and conclude with graph-based visualization of involved protein interaction networks as a basis for signaling. The different databases allowed for the construction of huge networks or specified ones consisting of high-confidence interactions only. Several genes associated to glioma were isolated via a network analysis from top hub nodes as well as from an outlier analysis. The latter approach highlights a mitogen-activated protein kinase next to a member of histondeacetylases and a protein phosphatase as genes uncommonly associated with glioma. Cluster analysis from top hub nodes lists several identified glioma-associated gene products to function within protein complexes, including epidermal growth factors as well as cell cycle proteins or RAS proto-oncogenes. -

Metabolic Tracing of NAD Precursors Using Strategically Labelled Isotopes of NMN

A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Metabolic tracing of NAD+ precursors using strategically labelled isotopes of NMN by Lynn-Jee Kim Supervisors Dr. Lindsay E. Wu (Primary) Prof. David A. Sinclair (Joint-Primary) Dr. Lake-Ee Quek (Co-supervisor) School of Medical Sciences Faculty of Medicine Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name: Kim Given Name/s: Lynn-Jee Abbreviation for degree as give in PhD the University calendar: Faculty: Faculty of Medicine School: School of Medical Sciences + Thesis Title: Metabolic tracing of NAD precursors using strategically labelled isotopes of NMN Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an important cofactor and substrate for hundreds of cellular processes involved in redox homeostasis, DNA damage repair and the stress response. NAD+ declines with biological ageing and in age-related diseases such as diabetes and strategies to restore intracellular NAD+ levels are emerging as a promising strategy to protect against metabolic dysfunction, treat age-related conditions and promote healthspan and longevity. One of the most effective ways to increase NAD+ is through pharmacological supplementation with NAD+ precursors such as nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) which can be orally delivered. Long term administration of NMN in mice mitigates age-related physiological decline and alleviates the pathophysiologies associated with a high fat diet- and age-induced diabetes. Despite such efforts, there are certain aspects of NMN metabolism that are poorly understood. In this thesis, the mechanisms involved in the utilisation and transport of orally administered NMN were investigated using strategically labelled isotopes of NMN and mass spectrometry. -

Polymorphisms in GC and NADSYN1 Genes Are Associated with Vitamin

Foucan et al. BMC Endocrine Disorders 2013, 13:36 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6823/13/36 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Polymorphisms in GC and NADSYN1 Genes are associated with vitamin D status and metabolic profile in Non-diabetic adults Lydia Foucan1,2,9*, Fritz-Line Vélayoudom-Céphise1,3, Laurent Larifla1, Christophe Armand1, Jacqueline Deloumeaux1, Cedric Fagour1, Jean Plumasseau4, Marie-Line Portlis5, Longjian Liu6, Fabrice Bonnet7 and Jacques Ducros8 Abstract Background: Our aim was to assess the associations between vitamin D (vitD) status, metabolic profile and polymorphisms in genes involved in the transport (Group-Component: GC) and the hydroxylation (NAD synthetase 1: NADSYN1) of 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) in non-diabetic individuals. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study with 323 individuals recruited from the Health Center of Guadeloupe, France. The rs2282679 T > G and rs2298849 T > C in GC and rs12785878 G > T in NADSYN1 were genotyped. Results: Mean age was 46(range 18–86) years. 57% of participants had vitD insufficiency, 8% had vitD deficiency, 61% were overweight and 58% had dyslipidemia. A higher frequency of overweight was noted in women carrying rs2298849T allele v CC carriers (71% v 50%; P = 0.035). The rs2282679G allele was associated with increased risks of vitD deficiency and vitD insufficiency (OR =3.53, P = 0.008, OR = 2.34, P = 0.02 respectively). The rs2298849 TT genotype was associated with vitD deficiency and overweight (OR =3.4, P = 0.004 and OR = 1.76, P = 0.04 respectively) and the rs12785878 GG genotype with vitD insufficiency and dyslipidemia (OR = 1.80, P = 0.01 and OR = 1.72, P = 0.03 respectively). -

The Role of Natural Selection in Human Evolution – Insights from Latin America

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 39, 3, 302-311 (2016) Copyright © 2016, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2016-0020 Review Article The role of natural selection in human evolution – insights from Latin America Francisco M. Salzano1 1Departamento de Genética, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Abstract A brief introduction considering Darwin’s work, the evolutionary synthesis, and the scientific biological field around the 1970s and subsequently, with the molecular revolution, was followed by selected examples of recent investiga- tions dealing with the selection-drift controversy. The studies surveyed included the comparison between essential genes in humans and mice, selection in Africa and Europe, and the possible reasons why females in humans remain healthy and productive after menopause, in contrast with what happens in the great apes. At the end, selected exam- ples of investigations performed in Latin America, related to the action of selection for muscle performance, acetylation of xenobiotics, high altitude and tropical forest adaptations were considered. Despite dissenting views, the influence of positive selection in a considerable portion of the human genome cannot presently be dismissed. Keywords: natural selection, human evolution, population genetics, human adaptation, history of genetics. Received: February 10, 2016; Accepted: May 8, 2016. History deniably indicated that we had derived from -

Vitamin D Status and Associated Genetic Polymorphisms in a Cohort of UK Children with Non- Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

ORIGINALRESEARCH doi:10.1111/ijpo.12293 Vitamin D status and associated genetic polymorphisms in a cohort of UK children with non- alcoholic fatty liver disease P. S. Gibson1,3, A. Quaglia2, A. Dhawan3,H.Wu1, S. Lanham-New1, K. H. Hart1, RESEARCH E. Fitzpatrick3,† and J. B. Moore1,4,† 1Department of Nutritional Sciences, School of Summary Biosciences and Medicine, Faculty of Health and Background: Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with non-alcoholic fatty Medical Sciences, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK; 2Institute of Liver Studies, King’s College liver disease (NAFLD). However, the role of polymorphisms determining vitamin D ORIGINAL London School of Medicine at King’s College status remains unknown. Hospital, London, UK; 3Pediatric Liver, GI and Objectives: The objectives of this study were to determine in UK children with Nutrition Centre, King’s College London School of Medicine at King’s College Hospital, London, biopsy-proven NAFLD (i) their vitamin D status throughout a 12-month period and UK; 4School of Food Science and Nutrition, (ii) interactions between key vitamin D-related genetic variants (nicotinamide adenine University of Leeds, Leeds, UK dinucleotide synthase-1/dehydrocholesterol reductase-7, vitamin D receptor, group-specific component, CYP2R1) and disease severity. †Joint senior authors. Methods: In 103 paediatric patients with NAFLD, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D Address for correspondence: (25OHD) levels and genotypes were determined contemporaneously to liver biopsy Dr. J Bernadette Moore, University of and examined in relation to NAFLD activity score and fibrosis stage. Leeds, School of Food Science and Nutrition, West Yorkshire, Leeds Results: Only 19.2% of children had adequate vitamin D status; most had mean fi < À1 fi LS2 9JT, UK. -

Cell Culture-Based Profiling Across Mammals Reveals DNA Repair And

1 Cell culture-based profiling across mammals reveals 2 DNA repair and metabolism as determinants of 3 species longevity 4 5 Siming Ma1, Akhil Upneja1, Andrzej Galecki2,3, Yi-Miau Tsai2, Charles F. Burant4, Sasha 6 Raskind4, Quanwei Zhang5, Zhengdong D. Zhang5, Andrei Seluanov6, Vera Gorbunova6, 7 Clary B. Clish7, Richard A. Miller2, Vadim N. Gladyshev1* 8 9 1 Division of Genetics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard 10 Medical School, Boston, MA, 02115, USA 11 2 Department of Pathology and Geriatrics Center, University of Michigan Medical School, 12 Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 13 3 Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 14 MI 48109, USA 15 4 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 16 48109, USA 17 5 Department of Genetics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10128, USA 18 6 Department of Biology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627, USA 19 7 Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA 02142, US 20 21 * corresponding author: Vadim N. Gladyshev ([email protected]) 22 ABSTRACT 23 Mammalian lifespan differs by >100-fold, but the mechanisms associated with such 24 longevity differences are not understood. Here, we conducted a study on primary skin 25 fibroblasts isolated from 16 species of mammals and maintained under identical cell culture 26 conditions. We developed a pipeline for obtaining species-specific ortholog sequences, 27 profiled gene expression by RNA-seq and small molecules by metabolite profiling, and 28 identified genes and metabolites correlating with species longevity. Cells from longer-lived 29 species up-regulated genes involved in DNA repair and glucose metabolism, down-regulated 30 proteolysis and protein transport, and showed high levels of amino acids but low levels of 31 lysophosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylethanolamine. -

Genome-Wide Association Study of Vitamin D Levels in Children: Replication in the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study

Genes and Immunity (2014) 15, 578–583 © 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1466-4879/14 www.nature.com/gene SHORT COMMUNICATION Genome-wide association study of vitamin D levels in children: replication in the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) study D Anderson1, BJ Holt1, CE Pennell2, PG Holt1, PH Hart1 and JM Blackwell1 This genome-wide association study (GWAS) utilises data from the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study for 25- hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels measured in blood collected at age 6 years (n = 673) and at age 14 years (n = 1140). Replication of significantly associated genes from previous GWASs was found for both ages. Genome-wide significant associations were found both at age 6 and 14 with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chromosome 11p15 in PDE3B/CYP2R1 (age 6: rs1007392, P = 3.9 × 10 − 8; age14: rs11023332, P = 2.2 × 10 − 10) and on chromosome 4q13 in GC (age 6: rs17467825, P = 4.2 × 10 − 9; age14: rs1155563; P = 3.9 × 10 − 9). In addition, a novel association was observed at age 6 with SNPs on chromosome 7p15 near NPY (age 6: rs156299, P = 1.3 × 10 − 6) that could be of functional interest in highlighting alternative pathways for vitamin D metabolism in this age group and merits further analysis in other cohort studies. Genes and Immunity (2014) 15, 578–583; doi:10.1038/gene.2014.52; published online 11 September 2014 INTRODUCTION RESULTS AND DISCUSSION In humans, vitamin D is obtained primarily through exposure to Descriptive statistics of the study participants are shown in ultraviolet B radiation from sunlight and secondarily through a Table 1. -

393LN V 393P 344SQ V 393P Probe Set Entrez Gene

393LN v 393P 344SQ v 393P Entrez fold fold probe set Gene Gene Symbol Gene cluster Gene Title p-value change p-value change chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21b /// chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21a /// chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21c 1419426_s_at 18829 /// Ccl21b /// Ccl2 1 - up 393 LN only (leucine) 0.0047 9.199837 0.45212 6.847887 nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin- 1447085_s_at 18018 Nfatc1 1 - up 393 LN only dependent 1 0.009048 12.065 0.13718 4.81 RIKEN cDNA 1453647_at 78668 9530059J11Rik1 - up 393 LN only 9530059J11 gene 0.002208 5.482897 0.27642 3.45171 transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily 1457164_at 277328 Trpa1 1 - up 393 LN only A, member 1 0.000111 9.180344 0.01771 3.048114 regulating synaptic membrane 1422809_at 116838 Rims2 1 - up 393 LN only exocytosis 2 0.001891 8.560424 0.13159 2.980501 glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 1433716_x_at 14586 Gfra2 1 - up 393 LN only 2 0.006868 30.88736 0.01066 2.811211 1446936_at --- --- 1 - up 393 LN only --- 0.007695 6.373955 0.11733 2.480287 zinc finger protein 1438742_at 320683 Zfp629 1 - up 393 LN only 629 0.002644 5.231855 0.38124 2.377016 phospholipase A2, 1426019_at 18786 Plaa 1 - up 393 LN only activating protein 0.008657 6.2364 0.12336 2.262117 1445314_at 14009 Etv1 1 - up 393 LN only ets variant gene 1 0.007224 3.643646 0.36434 2.01989 ciliary rootlet coiled- 1427338_at 230872 Crocc 1 - up 393 LN only coil, rootletin 0.002482 7.783242 0.49977 1.794171 expressed sequence 1436585_at 99463 BB182297 1 - up 393 -

NAD Metabolism in Health and Disease

Review TRENDS in Biochemical Sciences Vol.32 No.1 NAD+ metabolism in health and disease Peter Belenky, Katrina L. Bogan and Charles Brenner* Departments of Genetics and of Biochemistry and Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, NH 03756, USA Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is both a developing the nutritional deficiency pellagra unless their coenzyme for hydride-transfer enzymes and a substrate diet is supplemented with one of the classical vitamin for NAD+-consuming enzymes, which include ADP- precursors of NAD+, nicotinic acid (Na) or nicotinamide ribose transferases, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases, (Nam), which are collectively termed niacin. As shown in cADP-ribose synthases and sirtuins. Recent results Figure 2, the salvage pathways for the two niacins are establish protective roles for NAD+ that might be applic- encoded by different genes and, thus, might not be able therapeutically to prevent neurodegenerative con- expressed equally in all vertebrate tissues. The blood– ditions and to fight Candida glabrata infection. In borne bacterium Haemophilus influenza can not synthe- addition, the contribution that NAD+ metabolism makes size NAD+ de novo or salvage niacins (see Glossary). to lifespan extension in model systems indicates that Instead, it depends on uptake of nicotinamide riboside therapies to boost NAD+ might promote some of the (NR) and a bacterial pathway that converts NR to NAD+ beneficial effects of calorie restriction. Nicotinamide by phosphorylation and subsequent adenylylation [1]. riboside, the recently discovered nucleoside precursor Recently, it has become apparent that fungi and verte- of NAD+ in eukaryotic systems, might have advantages brates encode eukaryotic NR kinases (Nrk isozymes) to as a therapy to elevate NAD+ without inhibiting sirtuins, salvage NR, a third vitamin precursor of NAD+, which which is associated with high-dose nicotinamide, or occurs in milk [2].