Extirpation and Reintroduction of the Corsican Red Deer Cervus Elaphus Corsicanus in Corsica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fium'orbu Castellu Est Composée De 13 Communes

Fium’orbu Castellu Communauté de communes de Fium’orbu Castellu L'intercommunalité de Fium'orbu Castellu est composée de 13 communes. Elle s'étend de la mer Tyrrhénienne à l'Est au massif du Monte Renosu à l'Ouest. Sa densité de population est faible : 20 habitants au km², les zones de montagne atténuant le peuplement du littoral. En 2015, elle abrite 12 800 habitants, huit sur dix résident à Ghisonnaccia, Ventiseri et Solaro. Sa croissance démographique se fait au même rythme que celle de la région. Depuis 2010, elle est due exclusivement à l'apport migratoire, le solde naturel étant nul. Le revenu disponible des ménages se situe en deçà du niveau régional, 23 % d'entre eux vivent sous le seuil de pauvreté contre 20 % en Corse. Située sur la plaine orientale, l'EPCI a une économie fortement tournée vers l'agriculture : agrumes, vignes, kiwis… Le BTP y est également plus développé qu'au niveau régional tout comme l'industrie, notamment agroalimentaire et énergétique, cette dernière étant liée à l'implantation du barrage hydroélectrique de Sampolo sur le cours d'eau du Fium'orbo. Ainsi, parmi les 5 700 actifs de la communauté de commune, se dégage une présence marquée d'ouvriers et d'employés. Ils sont en outre huit sur dix à travailler et résider sur le territoire. Avec sa façade maritime et ses zones montagneuses propres aux randonnées, l'intercommunalité attire de nombreux touristes. Elle dispose de 7 700 lits touristiques marchands, soit 5 % de l'offre régionale. Cet hébergement est surtout centré sur les C IGN - Insee 2018 campings. -

Liste Des Électeurs Sénatoriaux En Haute-Corse

PRÉFECTURE DE LA HAUTE-CORSE ÉLECTIONS SÉNATORIALES du 27 septembre 2020 ********** Liste des électeurs sénatoriaux (dressé en application des dispositions de l'article R. 146 du code électoral) 1 / 49 1 – SÉNATEUR - CASTELLI Joseph 2 – DÉPUTÉS - ACQUAVIVA Jean-Félix - CASTELLANI Michel 3 - CONSEILLERS A L’ASSEMBLÉE DE CORSE - ARMANET Guy - ARRIGHI Véronique - BENEDETTI François - CARLOTTI Pascal - CASANOVA-SERVAS Marie-Hélène - CECCOLI François-Xavier - CESARI Marcel - COGNETTI-TURCHINI Catherine - DELPOUX Jean-Louis - DENSARI Frédérique - GHIONGA Pierre - GIUDICI Francis - GIOVANNINI Fabienne - GRIMALDI Stéphanie - MARIOTTI Marie-Thérèse - MONDOLONI Jean-Martin - MOSCA Paola - NIVAGGIONI Nadine - ORLANDI François - PADOVANI Marie-Hélène - PAOLINI Julien - PARIGI Paulu-Santu - PIERI Marie-Anne - POLI Antoine - PONZEVERA Juliette - POZZO di BORGO Louis - PROSPERI Rosa - SANTUCCI Anne-Laure - SIMEONI Marie - SIMONI Pascale - TALAMONI Jean-Guy - TOMASI Anne - TOMASI Petr’Antone - VANNI Hyacinthe 4 - DÉLÉGUÉS DES CONSEILS MUNICIPAUX -AGHIONE a) Délégué élu - CASANOVA André b) Suppléants - VIELES Francis - BARCELO Daniel - KLEINEIDAM Hervé -AITI a) Délégué élu - ORSONI Gérard b) Suppléants - ANGELI Marius -ALANDO a) Délégué élu - MAMELLI Guy b) Suppléants - IMPERINETTI Jean-Raphaël - POLETTI Cécile - BERNARDI Jean-François Albert -ALBERTACCE a) Délégué élu - ALBERTINI Pierre-François b) Suppléants - SANTINI Pasquin - ALBERTINI Catherine - ZAMBARO Flavia -ALERIA a) Délégués élus - LUCIANI Dominique - TADDEI Laurence - CHEYNET Patrick - HERMÉ -

Compte-Rendu Suivi De Projet

Compte-rendu Client : DREAL Corse Emetteur : Edwige REVELAT - BURGEAP Pierre PORTALIER N°Affaire : A34012 Date émission : 14/02/2014 N° contrat : CACISE131414 Lieu : Bastia Atelier n°2 – Transports Routiers Bastia – 03 février 2014 Objet du suivi : - Planning - Technique - Financier Résumé/Suite à donner Prochaine étape : La finalisation des fiches actions et la rédaction du projet de PPA Documents joints Exposé présenté par BURGEAP Ordre du jour 1. Introduction 2. Réduction des émissions du secteur Transports de Marchandises 3. Politique de livraison 4. Discussions sur les fiches actions issues de l’atelier 1 du 9 décembre 2013 5. Conclusions Compte-rendu – Bastia – Atelier n°2 – Thématique : Transports maritimes et ferroviaires – 3 février 2014 Page 1 sur 8 Listes des personnes présentes Nicolas BERNARDI – Qualitair Corse Jean-Luc SAVELLI – Qualitair Corse Patrick LANZALAVI – DDTM 2B Anthony CROCE – DDTM 2B Céline POTIER – LAPEYRE – Mairie de Bastia Hilaire TROJANI – Mairie de Lucciana Isabelle SALVADORI – Département de Haute-Corse Daniel SPAZZOLA - Département de Haute-Corse Ariel RISO – CTC, direction des routes Jean-Baptiste BARTOLI – Chemins de fer de la Corse Sophie FINIDORI – Agence d’Aménagement Durable, de Planification et d’Urbanisme de la Corse (AAUC) Stéphane CHEMINAN – CEREMA, Direction Territoriale Méditerranée Joseph MATTEI – ARS Corse Frédéric ABRAHAM – BURGEAP Edwige REVELAT – BURGEAP Christian PRADEL – DREAL Corse Pierre PORTALIER – DREAL Corse Valérie ROMANI – Communauté d’Agglomération de Bastia, service des transports urbains Cynthia CAVALLI – CTC, directrice des transports Compte-rendu – Bastia – Atelier n°2 – Thématique : Transports maritimes et ferroviaires – 3 février 2014 Page 2 sur 8 Plan de protection de l’atmosphère de la région bastiaise 1- Introduction La séance est ouverte par Monsieur Christian PRADEL de la DREAL Corse. -

Appel a Candidatures Du 08 J

Publication effectuée en application des articles L 141-1, L 141-3, L 143-3 et R 142-3 du Code Rural. La SAFER CORSE se propose, sans engagement de sa part, d’attribuer par RETROCESSION ou SUBSTITUTION, tous les Biens désignés ci-après qu’elle possède ou qu’elle envisage d’acquérir. La propriété ci-après désignée est mise en attribution sous réserve de la bonne finalité de l’opération d'acquisition par la SAFER Corse. ALERIA : Lieudit Ferragine : Section E n° 1126 – Lieudit Sualello : Section E n° 1121 (en partie), S.A.T. : 20a00ca à prendre sous réserve d’un Document d’Arpentage (DA), la superficie pourra varier dans une tolérance de plus ou moins 10%. (Présence d’une servitude de passage) En nature de : terre et friches (sans bâtiment) Classification dans un document d'urbanisme : Zone UD au P.L.U. de la Commune ALERIA : Lieudit Sualello : Section E n° 1121 (en partie), S.A.T. : 7 600 m² environ à prendre sous réserve d’un Document d’Arpentage (DA), la superficie pourra varier dans une tolérance de plus ou moins 10%. En nature de : terres et friches (sans bâtiment) Classification dans un document d'urbanisme : Environ 6 200 m², (superficie à prendre sous réserve), en Zone UD et environ 1 400 m² en Zone Agricole au P.L.U. de la Commune ALERIA : 13 a 03 ca : Lieudit Calviani : Section A n° 796-813 En nature de : terres et friches (sans bâtiment) Classification dans un document d'urbanisme : La parcelle A n°796 est classée en Zone Agricole au PLU de la Commune. -

Escapades En Haute-Corse

Escapades en Haute-Corse en solo, à deux, entre amis ou en famille, la Haute-Corse vous attend ! 2 Cap Corse Sport, nature, découverte A cheval Brando • U Cavallu di Brando Musée Tél : 04 95 33 94 02 Ersa • Le Centre equestre «Cabanné» Canari • «Conservatoire du costume corse» Tél : 06 10 70 65 21 - 04 95 35 63 19 Collection de costumes corses datant du 19e siècle réalisés par l’atelier de couture «Anima Canarese» Pietracorbara • U Cavallu di Pietracorbara Tél : 04 95 37 80 17 Tél : 06 13 89 56 05 Luri • Musée du Vin «A Mémoria di u Vinu» Rogliano-Macinaggio • U Cavallu di Rogliano Ce petit musée du vin propose de découvrir le travail du Ouverture toute l’année - Tél : 04 95 35 43 76 vigneron corse d’antan ainsi qu’un atelier d’initiation à la dégustation - Tél : 04 95 35 06 44 Sisco • Equinature (Ouvert toute l’année) Tél : 06 81 52 62 85 Luri • «Les Jardins Traditionnels du Cap Corse» L’Association Cap Vert : Conservatoire du Patrimoine Sisco • «A Ferrera» - Tél : 04 95 35 07 99 Végétal : du 15/04 au au 30/09 visites guidées ou libres : maison du goût (dégustations), et des expostions, jardin de plantes potagères, collections fruitières, espaces boisés A pied et flore sauvage - Tél : 04 95 35 05 07 Luri • «L’Amichi di u Rughjone» (infos randonée) Tél : 04 95 35 01 43 Nonza• «Eco musée du Cédrat» Tél : 04 95 37 82 82 Luri • Point Information Randonnée Cap Corse Tél : 04 95 35 05 81 Luri • «Altre Cime Randonnées» Tél : 04 95 35 32 59 Artisans-artistesMorsiglia • Sculpture bois - Tél : 04 95 35 65 22 Luri • Club de randonnée de «l’Alticcione» -

Corte and Corsica, Your New Home

DISCOVER YOUR CITY Campus France will guide you through your first steps in France and exploring Corte and Corsica, your new home. WELCOME TO CORTE/CORSICA - JULY 2021. - JULY Rubrik C (91) - Photos: DR - Cover photo: ©AdobeStock @olezzo photo: ©AdobeStock @olezzo Rubrik (91) - Photos: DR Cover C Production: YOUR ARRIVAL HOUSING INCORTE/CORSICA / IN CORTE/CORSICA / Student Welcome services at Université de Corse There are numerous solutions for housing in (Università di Corsica Pasquale Paoli) Corte: Student-only accommodations managed by CROUS, student housing and private residences, The first point of contact at Université de Corse and rooms in private homes. is the Mobility Office (Bureau de la mobilité) run What’s most important is to take care of this as by the International Relations Service (SRI) for early as possible, before your arrival: Corte is a free-mover international students (non-exchange small town with limited accommodation options, it students). is therefore essential to organize accommodation The Service des Relations Internationales has before arriving in Corse. set up a “rotating” Welcome Desk where several different services (CPAM, CROUS, CAF, Préfecture) work in turn to simplify administrative procedures A FEW TIPS for international students. Short-term housing Address: Université de Corse, Edmond Simeoni • The search engine on the Corte Tourist Building (level 1), Service des Relations Office websitemay help you find short-term Internationales, Mobility Office, Mariani Campus, accommodation: http://www.corte-tourisme.com/ -

Page 1 of 8 Comprehensive Report Species

Comprehensive Report Species - Cervus elaphus Page 1 of 8 << Previous | Next >> View Glossary Cervus elaphus - Linnaeus, 1758 Elk Taxonomic Status: Accepted Related ITIS Name(s): Cervus elaphus Linnaeus, 1758 (TSN 180695) French Common Names: wapiti Unique Identifier: ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.102257 Element Code: AMALC01010 Informal Taxonomy: Animals, Vertebrates - Mammals - Other Mammals © Larry Master Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Animalia Craniata Mammalia Artiodactyla Cervidae Cervus Genus Size: C - Small genus (6-20 species) Check this box to expand all report sections: Concept Reference Concept Reference: Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (editors). 2005. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference. Third edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Two volumes. 2,142 pp. Available online at: http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/. Concept Reference Code: B05WIL01NAUS Name Used in Concept Reference: Cervus elaphus Taxonomic Comments: In recent decades, most authors have included Cervus canadensis in C. elaphus; i.e., North American elk has been regarded as conspecific with red deer of western Eurasia. Geist (1998) recommended that C. elaphus and C. canadensis be regarded as distinct species. This is supported by patterns of mtDNA variation as reported by Randi et al. (2001). The 2003 Texas Tech checklist of North American mammals (Baker et al. 2003) adopted this change. Grubb (in Wilson and Reeder 2005) followed here included canadensis in C. elaphus. Conservation Status NatureServe Status Global Status: G5 Global Status Last Reviewed: 19Nov1996 Global Status Last Changed: 19Nov1996 Rounded Global Status: G5 - Secure Nation: United States National Status: N5 (05Sep1996) Nation: Canada National Status: N5 (06Mar2013) U.S. -

Arrêté 2B-2021-08-20-00001 Du 20 Août 2021

Arrêté n° 2B-2021-08-20-00001 en date du 20 août 2021 plaçant les unités hydrographiques du département de la Haute-Corse en « vigilance » ou en « alerte » sécheresse et portant mesures de limitation des usages de l’eau sur les territoires des communes situées dans les unités hydrographiques placées en « alerte » sécheresse. Le préfet de la Haute-Corse Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite, Chevalier des Palmes académiques Vu le Code de l’environnement, notamment son article L.211-3, relatif aux mesures de limitation provisoires des usages de l’eau en cas de sécheresse ou de risque de pénurie d’eau ; Vu le Code de la santé publique, notamment ses articles L.1321-1 à L.1321-10 ; Vu le Code rural et de la pêche maritime, notamment son article L.665-17-5 qui prescrit l’interdiction de l'irrigation des vignes aptes à la production de raisins de cuve du 15 août à la récolte ; Vu le décret n°2021-795 du 23 juin 2021 relatif à la gestion quantitative de la ressource en eau et à la gestion des situations de crise liées à la sécheresse ; Vu le décret du 7 mai 2019 portant nomination du préfet de la Haute-Corse – Monsieur François RAVIER ; Vu l’arrêté préfectoral n°2B-2018-07-18-001 du 18 juillet 2018 portant mise en place de mesures coordonnées et progressives de limitation des usages de l’eau en cas de sécheresse dans le département de la Haute-Corse ; Vu les conclusions du comité départemental ressources en eau, réuni en séance le 18 août 2021 à la préfecture de Bastia. -

Populations Légales En Vigueur À Compter Du 1Er Janvier 2020

Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2020 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 2B HAUTE-CORSE INSEE - décembre 2019 Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2020 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 2B - HAUTE-CORSE RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE SOMMAIRE Ministère de l'Économie et des Finances Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques Introduction..................................................................................................... 2B-V 88 avenue Verdier CS 70058 92541 Montrouge cedex Tableau 1 - Population des arrondissements ................................................ 2B-1 Tél. : 01 87 69 50 00 Directeur de la Tableau 2 - Population des cantons et métropoles ....................................... 2B-2 publication Jean-Luc Tavernier Tableau 3 - Population des communes.......................................................... 2B-3 INSEE - décembre 2019 INTRODUCTION 1. Liste des tableaux figurant dans ce fascicule Tableau 1 - Population des arrondissements Tableau 2 - Population des cantons et métropoles Tableau 3 - Population des communes, classées par ordre alphabétique 2. Définition des catégories de la population1 Le décret n° 2003-485 du 5 juin 2003 fixe les catégories de population et leur composition. La population municipale comprend les personnes ayant leur résidence habituelle sur le territoire de la commune, dans un logement ou une communauté, les personnes détenues dans les établissements pénitentiaires -

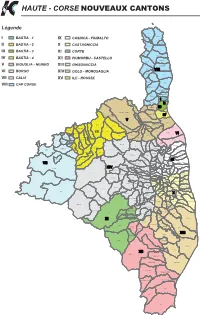

Decoupage Ok2014cantons Commune.Mxd

HAUTE - CORSE NOUVEAUX CANTONS Légende ERSA I IX ROGLIANO BASTIA - 1 CASINCA - FIUMALTO CENTURI II X TOMINO BASTIA - 2 CASTAGNICCIA MORSIGLIA MERIA III BASTIA - 3 XI CORTE PINO LURI IV BASTIA - 4 XII FIUMORBU - CASTELLO CAGNANO BARRETTALI V XIII BIGUGLIA - NEBBIO GHISONACCIA PIETRACORBARA CANARI VIIIVIII VI BORGO XIV GOLO - MOROSAGLIA OGLIASTRO SISCO VII CALVI XV ILE - ROUSSE OLCANI NONZA BRANDO VIII CAP CORSE OLMETA-DI-CAPOCORSO SANTA-MARIA-DI-LOTA SAN-MARTINO-DI-LOTA FARINOLE I BASTIA 1 PATRIMONIO IIII BASTIA 2 BARBAGGIO IIIIII BASTIA 3 SAINT-FLORENT SANTO-PIETRO-DI-TENDA POGGIO-D'OLETTA BASTIA 4 RAPALE IVIV SAN-GAVINO-DI-TENDA V OLETTA BIGUGLIA PALASCA OLMETA-DI-TUDA L'ILE-ROUSSE URTACA MONTICELLO VALLECALLE CORBARA BELGODERE XV NOVELLA RUTALI BORGO SANTA-REPARATA-DI-BALAGNA VIVI ALGAJOLA PIGNA SORIO LAMA MURATO AREGNO VILLE-DI-PARASO SANT'ANTONINO PIEVE COSTA OCCHIATANA SPELONCATO LUCCIANA LUMIO LAVATOGGIO CATERI SCOLCA VIGNALE AVAPESSA PIETRALBA BIGORNO VESCOVATO MURO NESSA LENTO CAMPITELLO FELICETO OLMI-CAPPELLA VOLPAJOLA MONTEGROSSO CASTIFAO PRUNELLI-DI-CASACCONI CALVI VENZOLASCA OLMO PIOGGIOLA VALLICA CAMPILE SORBO-OCAGNANO ZILIA CANAVAGGIA BISINCHI MONTE LORETO-DI-CASINCA CASTELLARE-DI-CASINCA MONCALE MAUSOLEO CROCICCHIA CASTELLO-DI-ROSTINO IXIX PENTA-ACQUATELLA MOLTIFAO PENTA-DI-CASINCA SILVARECCIO VIIVII VALLE-DI-ROSTINO ORTIPORIO PORRI CASABIANCA PIANO GIOCATOJO TAGLIO-ISOLACCIO MOROSAGLIA CASALTA XIVXIV PIEDIGRIGGIO CALENZANA POGGIO-MARINACCIO PRUNO TALASANI POPOLASCA QUERCITELLO SCATA CASTINETA FICAJA SAN-GAVINO-D'AMPUGNANIPERO-CASEVECCHIE -

9782402546041.Pdf

GHISONI GHISONI. — Partie sud-est. Partie nord et route vers Ghisonaccia MONOGRAPHIE DES COMMUNES DE CORSE GHISONI par Marc-François MARTELLI Ingénieur Général Honoraire de la ville de Paris Officier de la Légion d'Honneur Ancien Maire de Ghisoni 1960 1 ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES DE LA CORSE De tous temps, les peuples civilisés ont pris soin de conserver les titres établissant leurs droits et les documents qui témoi- gnent de leur passé. (ARCHIVES NATIONALES.) J'avais éteint mon flambeau, et la lune avec tous ses rayons entrait dans ma chambre et m'éclairait comme en plein jour. Je me levais et regardais la campagne, je voyais les chèvres marcher dans les sentiers du maquis et sur les collines ; çà et là, des feux de bergers, j'enten- dais leurs chants ; il faisait si beau qu'on eût dit le jour, mais un jour tout étrange, un jour de lune... Le ciel semblait haut, haut, et la lune avait l'air d'être lancée et perdue au milieu ; tout alentour elle éclairait l'azur, le pénétrait de blancheur, laissait tomber sur la vallée en pluie lumineuse ses vapeurs d'argent qui, une fois arrivées à terre, semblaient remonter vers elle comme de la fumée. G. FLAUBERT : Œuvres complètes : Par les champs et par les grèves, Pyrénées, Corse. Ghisoni (octobre 1840). La route entre Zonza et Ghisoni est très belle. J'aurais vingt ans de moins, je viendrais m'installer à Ospedale, Cozzano ou Ghisoni, dans la forêt de châtaigniers. A. GIDE : Journal (27 août 1930). CHAPITRE 1 Premières notions depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à la fin du XIV siècle Origine du nom - Descriptions des lieux Légende des Kyrie et Christe Eleison Dans sa notice historique sur l'île de Corse, l'abbé Letteron, ancien professeur agrégé au lycée de Bastia, écrit qu'il faut arriver à l'an 500 avant J.-C. -

Sylvoécorégion K13 Corse Orientale

Sylvoécorégion K13 Corse orientale La SER K 13 : Corse orientale K13 Corse orientale Mer de Ligurie regroupe cinq régions forestières Limite de région forestière nationales : 2B1 Cap corse - le Cap corse (2B.1) au nord ; 2B5 Nebbio et pays de Tende ¯ 2B4 Sillon de Corte - le Nebbio et pays de Tende 2B3 Castagniccia (2B.5) au nord-ouest ; 2B2 Plaine corse orientale 01020km le Sisco - le Sillon de Corte (2B.4) à Parc naturel régional l’ouest ; Limite de département 2B1 - la Castagniccia (2B.3) au centre ; - la Plaine corse orientale (2B.2) à l’est et au sud. St-Florent Région côtière tout entière com- prise dans le département de la 2B5 Haute-Corse, limitée à l’ouest par la SER K 12 : Montagne corse et, au nord-ouest et au sud-est, par la SER Calvi 2B4 K 11 : Corse occidentale, elle corres- 2B3 pond à la Corse schisteuse, distincte du reste de l’île, qui est cristallin. Omessa La corse orientale comprend les par- Haute-Corse ties éponymes du parc naturel régio- Corte nal (PNR) de Corse, en Castagniccia, Mer Tyrrhénienne au nord, et au sud de Ghisonaccia. golfe de Porto Porto Corse Crédit photo : E. Bruno, IGN. Bruno, E. Crédit photo : Venaco 2B2 Aléria Ghisonaccia golfe de Sagone Corse- du-Sud golfe Solenzara d'Ajaccio Sources : BD CARTO® IGN, BD CARTHAGE® IGN Agences de l'Eau, MNHN. Les régions forestières nationales de la SER K 13 : Corse orientale Caractéristiques particulières à la SER Cette région est la seule partie non cristalline de la Corse, d’où son ap- pellation de Corse schisteuse.