Changes in Israel's Countryside and Agriculture: the Opinions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beit Berl English Times 5Th Issue 2013 - 2014 the Faculty of Education English Department

The Beit Berl English Times 5th Issue 2013 - 2014 The Faculty of Education English Department Student Conference, the English Department - 2014 Book of Abstracts PARALLEL WORKSHOPS A Taste of Debate - Learn How to Argue Like the Boss Alon Cohen, Bar Ilan University, Netanya Academic College, YCI Center for Debating and Rhetoric Abstract: In this workshop we will briefly learn how to construct a convincing claim and then practice it in different ways. Alon Cohen is the project director at the YCI center for debating and Rhetoric. He has been coaching and teaching debate for the last five years and was the chief adjudicator of the first English tournament for high school students in 2012 conducted by the Ministry of Education. He teaches debating in Bar Ilan University, Netanya Academic College and coaches the Israeli national high school team. Debating achievements: Winner of the 2012 national championship in Hebrew, Winner of the 2011 English Open in Israel. (Biggest English tournament held in Israel preparing for the European Universities debating Championship) Quarter finalist in 2011 EUDC in Galway. Semi Finalist in the 2010 Red Sea Open. Winner of the 2010 Shantou University debating tournament (Held in China as part of the University's English Festival) The Assessment Battery of Basic Literacy in English kit (ABLE) Dr. Susie Russak, Beit Berl Academic College The Beit Berl English Times 5th Issue 2013 - 2014 The Faculty of Education English Department Abstract: The Assessment Battery of Basic Literacy in English kit (ABLE) The focus of English as a foreign language (EFL) instruction in the early elementary years is on acquiring basic literacy skills. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Sukkot Real Estate Magazine

SUKKOT 2020 REAL ESTATE Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Living the high Life LETTER FROM THE EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Readers, With toWers Welcome to the Sukkot edition of The Jerusalem THE ECONOMY: A CHALLENGING CONUNDRUM ....................08 Post’s Real Estate/Economic Post magazine. Juan de la Roca This edition is being published under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic. Although not all the articles herein are related to the virus, it is a reality BUILDING A STRONGER FUTURE ............................................... 12 that cannot be ignored. -

Yarqon River Basin Total Population

OUR VISION To create a region, the Central Yarqon, that will be the pride of its surrounding population by strengthening and deepening their involvement in planning, REHABILITATION OF THE CENTRAL YARQON RIVER developing and participation in its management. Connecting the surrounding population to the river area - Building civil society awareness, knowledge and participation in the Central Yarqon project by forming community groups based on thematic issues of interest that will participate in the project’s planning process and implementation as well as the management of the area in the future. This will build and enhance local patriotism and a sense of responsibility towards the area. Ecology and environment - Rehabilitate the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems of the streams and their corridors to a high degree of reliability. Hydrology – Planning of water resource management from a trans-boundary watershed perspective, comprised of rainwater and surface runoff management, and flood Planned Housing alleviation in both developed and open areas. Joint regional management – Creating a joint management committee comprised of representatives from the public, local authorities and the additional stakeholders. Hod Hasharon Planned Housing DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT AREA AND MAIN REASONING FOR ITS CHOICE Planned Housing Planned Housing The project area is in the heart of the Yarqon River basin, in the center of the most densely populated area in Israel, home to approx. 1.3 mill. people living in 12 municipalities that surround the area. The municipalities include major cities whose P & Industry Hod Hasharon inhabitants are from a variety of sectors, including two Jewish religious municipalities, three from the Arab sector and P several from lower socio-economic statuses. -

Le Voice of the Southern African Community in Israel

"le voice of the Southern African Community in Israel cjv-idi) ® m m n a i l Mf10 ° a WMifc 0DD ra?scjipses Telfed's newest housing project appeals to veteran and new immigrants alike. T ■ asa "rZ ' ■ ^ , / C " ™ ■ m laMgaaW ■ t„ ■ ^ m ■ 11 ■ - T B " " ■ 'II ■ M '-^mm ■' K.jL m mm* f mm » I ■ > w m ■ ■ w ■ ■■:l ' Education and the Law iEATiURE^lHam The past revisKed Femme Fatale lossad legend laid to rest Denunciation liMliljMi Maureen Fain depicts the palft i The Wondering Jew Dr. Isaac Kaplan's entertaining anecdotes ■NUPTIAl^.i^NE-W ■ARRIVALS.; A South African Zionist Federation (Israel) publication ' TELFED MAGAZINE "The voice of the Southern African Community in Israel" Thirty years of connecting with the community. 1975-2005 With its finger on the pulse, Telfed magazine has for three decades kept its readership abreast of news of interest to the Southern African community in Israel. The mouthpiece of the SAZF (ISRAEL), it has served in bringing to the attention of the community its projects and activities, as it is presently performing in promoting Teifed's iatest housing project in Modi'in,(See enclosed flyer) Please join us in ceiebrating this momentous milestone by placing" your personal or business message of good wishes in the next Telfed Magazine. Your contributions will help our magazine main tain its high standard and hopefuliy expand its horizons. 1. Add your name to the good wishes page NIS 50.00 2. Send a personal or business message 1 / 8 p a g e N I S 2 0 0 . -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”............................................................................. -

Overseas Travel — May 2019 PIRSA Chief Executive

Overseas Travel — May 2019 PIRSA Chief Executive No of Destination Reasons for Travel Outcomes of Travel Travel Total Cost Travel travellers Itinerary.' of Travel2 Receipts3 1 Israel The mission had a Enhancing the commercialisation of See $26.464.58 See strong focus on AgTech innovation and adoption of attached attached (24 May 2019 to AgTech, agricultural new technologies by South 3 June 2019) research Australian primary producers is a key development and priority for the Primary Industries corn mercialisation. portfolio, and will assist to achieve the Government's ambition to increase agricultural production and support the Government's 3% economic growth target. Approved for publication Example disclaimer - Note: These details are correct as at the date approved for publication. Figures may be rounded and have not been audited. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (BY) 3.0 Australia Licence htto://creativecomrnons.oroilicensesiby/3.01aut To attribute this material, cite Government of South Australia I Scanned copies of itineraries to be attached. 2 Excludes salary costs. 3 Scanned copies of all receipts/invoices to be attached. minumx-tnnw, -Irma 1130 M3N7P1X1 13`771 P3 Australia-Israel Israel-Australia, New Zealand & Oceania Chamber of Commerce Chamber Of Commerce AICC (SA) Trade Mission to Israel PARTICIPATION BY: HON. TIM WHETSTONE MP MINISTER FOR PRIMARY INDUSTRIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT (SA) MARK ALLISON CEO - ELDERS Saturday 25th May Saturday 1st June, 2019 11 Page AICC SA TRADE DELEGATE LIST: Delegates • Company 1. Hon. Tim Whetstone MP —Minister Minister for Primary Industries & Regional Development (SA) Mr. Scott Ashby Chief Executive Primary Industries and Regions . -

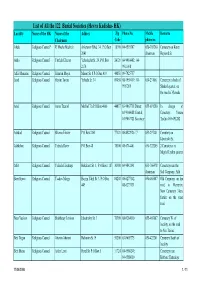

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

The Dairy Industry in Israel 2006

THE DAIRY INDUSTRY IN ISRAEL 2006 Israel Cattle Breeders Association Israel Dairy Board The Dairy Industry in Israel 2006 Editors: Daniel Hojman – Extension Service, Ministry of Agriculture Yossi Malul – Israel Cattle Breeders Association Tova Avrech – Israel Dairy Board Design and Production: Moshe Mirsky Aknowledgments: Rachel Borushek – Israel Farmers’ Federation Ephraim Ezra – ICBA, Israeli Herdbook Israel Flamenbaum – Extension Service, Ministry of Agriculture Shmuel Friedman – IDB – National Service for Udder Health and Milk Quality Boaz Hanochi – ICBA Ezra Shoshani – Extension Service, Ministry of Agriculture Liron Tamir – Israel Dairy Board Joel I. Weller – Department of Genetics, Institute of Animal Sciences, A.R.O. Yoel Zeron – Sion A.I. Company Doron Zilcer – Tnuva Dairy Industry Sponsorships: “Hahaklait”, Mutual Society for Clinical Veterinary Services Sion A.I. Company S.A.E. Afikim Ambar Feed Mills Lachish Industries Ltd. S.C.R. Engineers Ltd. Tnuva Contents PART 1 The Israeli Dairy Industry Map of the Dairy Industry in Israel 4 The Dairy Industry in Israel 5 The Agriculture Sector in Israel – Rachel Borushek 6 Dairy Farming in Israel 7 PART 2 Milk Production in Israel The Israeli Dairy Board – Tova Avrech 8 Structure of Israel Dairy Board 9 Annual Milk Quota and Milk Supply – Liron Tamir 10 The Reforme in the Israeli Dairy Farms 1999-2006 11 National Service for Udder Health & Milk Quality – Shmuel Fridmann 12 Milk Quality 13 Milk Marketing – Tova Avrech 15 Annual Marketed Milk 16 Research Fund 2006 17 Dairy Processing -

Imagining the Border

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1. -

Alternative NGO Report: Information for Establishing List of Issues for The

Alternative NGO Report: Information for Establishing List of Issues for the State of Israel before the The Committee on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Submitted by Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality (NCF) April 2012 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................3 II. List of Tables and Maps..........................................................................................................4 II. Introduction.............................................................................................................................5 Presentation of NGO..............................................................................................................5 Methodology of Report..........................................................................................................5 Historical Context ..................................................................................................................6 Current Socio-economic Situation…………………………………………………………..7 Government-planned towns .....................................................................................7 Newly recognized townships ....................................................................................7 “Unrecognized villages”: non-existent and illegal .................................................7 IV. Substantive Section ...............................................................................................................9