HSV-1 Single-Cell Analysis Reveals the Activation of Anti-Viral And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structure and Expression of Class II Defective Herpes Simplex Virus

JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY, Aug. 1982, p. 574-593 Vol. 43, No. 2 0022-538X/82/080574-20$02.00/0 Structure and Expression of Class II Defective Herpes Simplex Virus Genomes Encoding Infected Cell Polypeptide Number 8 HILLA LOCKER,1t NIZA FRENKEL,l* AND IAN HALLIBURTON2 Department ofBiology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637,1 and Department of Microbiology, University ofLeeds, Leeds, England' Received 12 February 1982/Accepted 13 May 1982 Defective genomes present in serially passaged virus stocks derived from the tsLB2 mutant of herpes simplex virus type 1 were found to consist of repeat units in which sequences from the UL region, within map coordinates 0.356 and 0.429 of standard herpes simplex virus DNA, were covalently linked to sequences from the end of the S component. The major defective genome species consisted of repeat units which were 4.9 x 106 in molecular weight and contained a specific deletion within the UL segment. These tsLB2 defective genomes were stable through more than 35 sequential virus passages. The ratios of defective virus genomes to helper virus genomes present in different passages fluctuated in synchrony with the capacity of the passages to interfere with standard virus replication. Cells infected with passages enriched for defective genomes overpro- duced the infected cell polypeptide number 8, which had previously been mapped within the UL sequences present in the tsLB2 defective genomes. In contrast, the synthesis of most other infected cell polypeptides was delayed and reduced. The abundant synthesis of infected cell polypeptide number 8 followed the , regula- tory pattern, as evident from kinetic studies and from experiments in which cycloheximide, canavanine, and phosphonoacetate were used. -

THE ROLE of the HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS TYPE 1 UL28 PROTEIN in TERMINASE COMPLEX ASSEMBLY and FUNCTION by Jason Don Heming Bachelor

THE ROLE OF THE HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS TYPE 1 UL28 PROTEIN IN TERMINASE COMPLEX ASSEMBLY AND FUNCTION by Jason Don Heming Bachelor of Science, Clarion University of Pennsylvania, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF MEDICINE This dissertation was presented by Jason Don Heming It was defended on April 18, 2013 and approved by Michael Cascio, Associate Professor, Bayer School of Natural and Environmental Sciences James Conway, Associate Professor, Department of Structural Biology Neal DeLuca, Professor, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Saleem Khan, Professor, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Dissertation Advisor: Fred Homa, Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics ii Copyright © by Jason Don Heming 2013 iii THE ROLE OF THE HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS TYPE 1 UL28 PROTEIN IN TERMINASE COMPLEX ASSEMBLY AND FUNCTION Jason Don Heming, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Herpes simplex virus type I (HSV-1) is the causative agent of several pathologies ranging in severity from the common cold sore to life-threatening encephalitic infection. During productive lytic infection, over 80 viral proteins are expressed in a highly regulated manner, resulting in the replication of viral genomes and assembly of progeny virions. Cleavage and packaging of replicated, concatemeric viral DNA into newly assembled capsids is critical to virus proliferation and requires seven viral genes: UL6, UL15, UL17, UL25, UL28, UL32, and UL33. Analogy with the well-characterized cleavage and packaging systems of double-stranded DNA bacteriophage suggests that HSV-1 encodes for a viral terminase complex to perform these essential functions, and several studies have indicated that this complex consists of the viral UL15, UL28, and UL33 proteins. -

Herpes Simplex Virus 1 ICP8 Mutant Lacking Annealing Activity Is Deficient for Viral DNA Replication

Herpes simplex virus 1 ICP8 mutant lacking annealing activity is deficient for viral DNA replication Savithri Weerasooriyaa,1, Katherine A. DiScipioa,b,1, Anthar S. Darwisha,b, Ping Baia, and Sandra K. Wellera,2 aDepartment of Molecular Biology and Biophysics, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT 06030; and bMolecular Biology and Biochemistry Graduate Program, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT 06030 Edited by Jack D. Griffith, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, and approved December 4, 2018 (received for review October 13, 2018) Most DNA viruses that use recombination-dependent mechanisms culating in patient populations (18–22). Additionally, it has long to replicate their DNA encode a single-strand annealing protein been recognized that viral replication intermediates are com- (SSAP). The herpes simplex virus (HSV) single-strand DNA binding posed of complex X- and Y-branched structures as evidenced by protein (SSB), ICP8, is the central player in all stages of DNA electron microscopy (10, 16) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis replication. ICP8 is a classical replicative SSB and interacts physi- (15, 23, 24). ′ ′ cally and/or functionally with the other viral replication proteins. The HSV exo/SSAP, composed of a 5 -to-3 exonuclease Additionally, ICP8 can promote efficient annealing of complemen- (UL12) and an SSAP (ICP8), is capable of promoting strand ex- tary ssDNA and is thus considered to be a member of the SSAP change in vitro (25, 26). More recently, we have shown that HSV infection stimulates single-strand annealing (27), and ICP8 has family. The role of annealing during HSV infection has been been reported to promote recombineering in transfected cells difficult to assess in part, because it has not been possible to (28). -

Type of the Paper (Article

Viruses 2018 – Breakthroughs in Viral Replication Faculty of Biology University of Barcelona Spain 7 – 9 February 2018 Conference Chair Eric O. Freed Conference Co-Chair Albert Bosch Organised by Conference Secretariat Antonio Peteira Man Luo George Andrianou Nikoleta Kiapidou Kristjana Xhuxhi Pablo Velázquez Lucia Russo Sara Martínez Lynn Huang Sarai Rodríguez Viruses 2018 – Breakthroughs in Viral Replication 1 CONTENTS Abridged Programme 5 Conference Programme 6 Welcome 13 General Information 15 Abstracts – Session 1 25 General Topics in Virology Abstracts – Session 2 45 Structural Virology Abstracts – Session 3 67 Virus Replication Compartments Abstracts – Session 4 89 Replication and Pathogenesis of RNA viruses Abstracts – Session 5 105 Genome Packaging and Replication/Assembly Abstracts – Session 6 127 Antiviral Innate Immunity and Viral Pathogenesis Abstracts – Poster Exhibition 147 List of Participants 297 Viruses 2018 – Breakthroughs in Viral Replication 3 Viruses 2018 – Breakthroughs in Viral Replication 7 – 9 February 2018, Barcelona, Spain Wednesday Thursday Friday 7 February 2018 8 February 2018 9 February 2018 S3. Virus S5. Genome Check-in Replication Packaging and Compartments Replication/Assembly Opening Ceremony S1. General Topics in Virology Morning Coffee Break S1. General Topics S3. Virus S5. Genome in Virology Replication Packaging and Compartments Replication/Assembly Lunch S2. Structural S4. Replication and S6. Antiviral Innate Virology Pathogenesis of Immunity and Viral RNA Viruses Pathogenesis Coffee Break Apéro and Poster Coffee Break Session S2. Structural S6. Antiviral Innate Virology Immunity and Viral Afternoon Conference Group Pathogenesis Photograph Closing Remarks Conference Dinner Wednesday 7 February 2018: 08:00 - 12:30 / 14:00 - 18:00 / Conference Dinner: 20:30 Thursday 8 February 2018: 08:30 - 12:30 / 14:00 - 18:30 Friday 9 February 2018: 08:30 - 12:30 / 14:00 - 18:15 Viruses 2018 – Breakthroughs in Viral Replication 5 Conference Programme Wednesday 7 February 08:00 – 08:45 Check-in 08:45 – 09:00 Opening Ceremony by Eric O. -

Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Oril Is Not Required for Virus Infection In

JOURNAL OF VIROLOGY, Nov. 1987, p. 3528-3535 Vol. 61, No. 11 0022-538X/87/113528-08$02.00/0 Copyright C 1987, American Society for Microbiology Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 oriL Is Not Required for Virus Replication or for the Establishment and Reactivation of Latent Infection in Mice MARYELLEN POLVINO-BODNAR, PAULO K. ORBERG, AND PRISCILLA A. SCHAFFER* Laboratory of Tumor Virus Genetics, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 Received 11 May 1987/Accepted 31 July 1987 During the course of experiments designed to isolate deletion mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the gene encoding the major DNA-binding protein, ICP8, a mutant, d61, that grew efficiently in ICP8-expressing Vero cells but not in normal Vero cells was isolated (P. K. Orberg and P. A. Schaffer, J. Virol. 61:1136-1146, 1987). d61 was derived by cotransfection of ICP8-expressing Vero cells with infectious wild-type viral DNA and a plasmid, pDX, that contains an engineered 780-base-pair (bp) deletion in the ICP8 gene, as well as a spontaneous -55-bp deletion in OriL. Gel electrophoresis and Southern blot analysis indicated that d61 DNA carried both deletions present in pDX. The ability of d61 to replicate despite the deletion in OriL suggested that a functional OriL is not essential for virus replication in vitro. Because d61 harbored two mutations, a second mutant, ts+7, with a deletion in oriL-associated sequences and an intact ICP8 gene was constructed. Both d61 and ts+7 replicated efficiently in their respective permissive host cells, although their yields were slightly lower than those of control viruses with intact oriL sequences. -

Topological Analysis of the Gp41 MPER on Lipid Bilayers Relevant to the Metastable HIV-1 Envelope Prefusion State

Topological analysis of the gp41 MPER on lipid bilayers relevant to the metastable HIV-1 envelope prefusion state Yi Wanga,b, Pavanjeet Kaurc,d, Zhen-Yu J. Sune,1, Mostafa A. Elbahnasawya,b,2, Zahra Hayatic,d, Zhi-Song Qiaoa,b,3, Nhat N. Buic, Camila Chilea,b,4, Mahmoud L. Nasre,5, Gerhard Wagnere, Jia-Huai Wanga,f, Likai Songc, Ellis L. Reinherza,b,6, and Mikyung Kima,g,6 aLaboratory of Immunobiology, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02115; bDepartment of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; cNational High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306; dDepartment of Physics, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306; eDepartment of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; fDepartment of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02215; and gDepartment of Dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215 Edited by Peter Palese, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, and approved September 23, 2019 (received for review July 18, 2019) The membrane proximal external region (MPER) of HIV-1 envelope immunologically vulnerable epitopes targeted by several of the most glycoprotein (gp) 41 is an attractive vaccine target for elicitation of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) developed during the broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) by vaccination. However, course of natural HIV-1 infection (10–13). Insertion, deletion, current details regarding the quaternary structural organization of and mutations of residues in the MPER defined the functional the MPER within the native prefusion trimer [(gp120/41)3] are elu- importance of the MPER in Env incorporation, viral fusion, and sive and even contradictory, hindering rational MPER immunogen infectivity (14–16). -

Viroporins: Structures and Functions Beyond Cell Membrane Permeabilization

Editorial Viroporins: Structures and Functions beyond Cell Membrane Permeabilization José Luis Nieva 1,* and Luis Carrasco 2,* Received: 17 September 2015 ; Accepted: 21 September 2015 ; Published: 29 September 2015 Academic Editor: Eric O. Freed 1 Biophysics Unit (CSIC, UPV/EHU) and Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), P.O. Box 644, 48080 Bilbao, Spain 2 Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa (CSIC, UAM), c/Nicolás Cabrera, 1, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.L.N.); [email protected] (L.C.); Tel.: +34-94-601-3353 (J.L.N.); +34-91-497-8450 (L.C.) Viroporins represent an interesting group of viral proteins that exhibit two sets of functions. First, they participate in several viral processes that are necessary for efficient production of virus progeny. Besides, viroporins interfere with a number of cellular functions, thus contributing to viral cytopathogenicity. Twenty years have elapsed from the first review on viroporins [1]; since then several reviews have covered the advances on viroporin structure and functioning [2–8]. This Special Issue updates and revises new emerging roles of viroporins, highlighting their potential use as antiviral targets and in vaccine development. Viroporin structure. Viroporins are usually short proteins with at least one hydrophobic amphipathic helix. Homo-oligomerization is achieved by helix–helix interactions in membranes rendering higher order structures, forming aqueous pores. Progress in viroporin structures during the last 2–3 years has in some instances provided a detailed knowledge of their functional architecture, including the fine definition of binding sites for effective inhibitors. -

How Influenza Virus Uses Host Cell Pathways During Uncoating

cells Review How Influenza Virus Uses Host Cell Pathways during Uncoating Etori Aguiar Moreira 1 , Yohei Yamauchi 2 and Patrick Matthias 1,3,* 1 Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, 4058 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Life Sciences, School of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TD, UK; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Sciences, University of Basel, 4031 Basel, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Influenza is a zoonotic respiratory disease of major public health interest due to its pan- demic potential, and a threat to animals and the human population. The influenza A virus genome consists of eight single-stranded RNA segments sequestered within a protein capsid and a lipid bilayer envelope. During host cell entry, cellular cues contribute to viral conformational changes that promote critical events such as fusion with late endosomes, capsid uncoating and viral genome release into the cytosol. In this focused review, we concisely describe the virus infection cycle and highlight the recent findings of host cell pathways and cytosolic proteins that assist influenza uncoating during host cell entry. Keywords: influenza; capsid uncoating; HDAC6; ubiquitin; EPS8; TNPO1; pandemic; M1; virus– host interaction Citation: Moreira, E.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Matthias, P. How Influenza Virus Uses Host Cell Pathways during 1. Introduction Uncoating. Cells 2021, 10, 1722. Viruses are microscopic parasites that, unable to self-replicate, subvert a host cell https://doi.org/10.3390/ for their replication and propagation. Despite their apparent simplicity, they can cause cells10071722 severe diseases and even pose pandemic threats [1–3]. -

An Exploration of the Interplay Between HSV-1 and the Non-Homologous End Joining Proteins PAXX and DNA-Pkcs

An exploration of the interplay between HSV-1 and the non-homologous end joining proteins PAXX and DNA-PKcs Benjamin James Trigg Gonville and Caius College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 2. Abstract An exploration of the interplay between HSV-1 and the non-homologous end joining proteins PAXX and DNA-PKcs Benjamin James Trigg Abstract DNA damage response (DDR) pathways are essential in maintaining genomic integrity in cells, but many DDR proteins have other important functions such as in the innate immune sensing of cytoplasmic DNA. Some DDR proteins are known to be beneficial or restrictive to viral infection, but most remain uncharacterised in this respect. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is a mechanism of double stranded DNA (dsDNA) repair that functions to rapidly mend broken DNA ends. The NHEJ machinery is well characterised in the context of DDR but recent studies have linked the same proteins to innate immune DNA sensing and, hence, anti-viral responses. The aim of this thesis is to further investigate the interplay between herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), a dsDNA virus, and two NHEJ proteins, DNA protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA- PKcs) and paralogue of XRCC4 and XLF (PAXX). PAXX was first described in the literature as a NHEJ protein in 2015, but whether it has any role in the regulation of virus infection has not been established. Here we show that PAXX acts as a restriction factor for HSV-1 because PAXX-/- (KO) cells produce a consistently higher titre of HSV-1 than the respective wild type (WT) cells. -

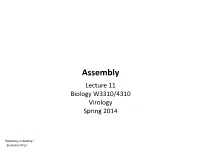

Assembly Lecture 11 Biology W3310/4310 Virology Spring 2014

Assembly Lecture 11 Biology W3310/4310 Virology Spring 2014 “Anatomy is des.ny.” --SIGMUND FREUD All virions complete a common set of assembly reac3ons * common to all viruses common to many viruses ©Principles of Virology, ASM Press The structure of a virus parcle determines how it is formed ©Principles of Virology, ASM Press Assembly is dependent on host cell machinery • Cellular chaperones • Transport systems • Secretory pathway • Nuclear import and export machinery Concentrang components for assembly: Nothing happens fast in dilute solu1ons • Viral components oSen visible by light microscopy (‘factories’ or ‘inclusions’) • Concentrate proteins on internal membranes (poliovirus) • Negri bodies (rabies virus) Viral proteins have ‘addresses’ built into their structure • Membrane targeYng: Signal sequences, fa\y acid modificaons • Membrane retenYon signals • Nuclear localizaYon sequences (NLS) • Nuclear export signals 414 Localiza3on of viral proteins to the nucleus CHAPTER 12 Golgi apparatus Ribosome Rough endoplasmic reticulum Plasma membrane Py(VP1) + VP2/3 Ad hexon + 5 100 kDa Nuclear envelope: Outer nuclear membrane Inner nuclear membrane Nucleus Nuclear pore complex Mitochondrion Cytoskeleton: Influenza virus NP Intermediate filament Microtubule Actin filament bundle Extracellular matrix ©Principles of Virology, ASM Press Figure 12.1 Localization of viral proteins to the nucleus. The nucleus and major membrane-bound compartments of the cytoplasm, as well as components of the cytoskeleton, are illustrated schematically and not to scale. Viral proteins destined for the nucleus are synthesized by cytoplasmic polyribosomes, as illustrated for the infl uenza virus NP protein. They engage with the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear pore complex and are translocated into the nucleus by the protein import machinery of the host cell. -

(Infected Cell Protein 8) of Herpes Simplex Virus L*

THEJOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY Vol. 262, No. 9, Issue of March 25, pp. 4260-4266, 1987 0 1987 by The American Society of Biological Chemists, Inc Printed in U.S. A. Interaction between theDNA Polymerase and Single-stranded DNA- binding Protein (Infected Cell Protein 8) of Herpes Simplex Virus l* (Received for publication, September 22, 1986) Michael E. O’DonnellS, Per EliasQ,Barbara E. Funnellll, and I. R. Lehman From the Department of Biochemistry, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California 94305 The herpes virus-encoded DNA replication protein, ICP8 completely inhibits replication of singly primed ssDNA infected cell protein 8 (ICPS), binds specifically to templates by the herpespolymerase. On the other hand, ICP8 single-stranded DNA with a stoichiometry of one ICPS strongly stimulates replication of duplex DNA. It does so, molecule/l2 nucleotides. In the absence of single- however, onlyin the presence of anuclear extract from stranded DNA, it assembles into long filamentous herpes-infected cells. structures. Binding of ICPS inhibits DNA synthesis by the herpes-induced DNA polymerase on singly primed EXPERIMENTALPROCEDURES single-stranded DNA circles. In contrast, ICPS greatly Materials-DNase I and venom phosphodiesterase were obtained stimulates replication of circular duplex DNA by the from Worthington. The syntheticoligodeoxynucleotide (44-mer) was polymerase. Stimulation occurs only in the presence of synthesized by the solid-phase coupling of protected phosphoramidate a nuclear extract from herpes-infected cells. Appear- nucleoside derivatives (11).3H-Labeled #X ssDNA was a gift from ance of the stimulatory activity in nuclear extracts Dr. R. Bryant (this department). pMOB45 (10.5 kilobases) linear coincides closely with the time of appearance of her- duplex plasmid DNA was a gift from Dr. -

The Neural F-Box Protein NFB42 Mediates the Nuclear Export of the Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Replication Initiator Protein (UL9 Protein) After Viral Infection

The neural F-box protein NFB42 mediates the nuclear export of the herpes simplex virus type 1 replication initiator protein (UL9 protein) after viral infection Chi-Yong Eom*, Won Do Heo†, Madeleine L. Craske†, Tobias Meyer†, and I. Robert Lehman*‡ Departments of *Biochemistry and †Molecular Pharmacology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305-5307 Contributed by I. Robert Lehman, February 3, 2004 The neural F-box 42-kDa protein (NFB42) is a component of the in nonneural tissues (11). The factors required for ubiquitination SCFNFB42 E3 ubiquitin ligase that is expressed in all major areas of and subsequent degradation of target proteins are found the brain; it is not detected in nonneuronal tissues. We previously throughout the cell, including the cytosol, nucleus, endoplasmic identified NFB42 as a binding partner for the herpes simplex virus reticulum, and cell-surface membranes (9, 12). 1 (HSV-1) UL9 protein, the viral replication-initiator, and showed Because NFB42 is found primarily in the cytosol (11), whereas that coexpression of NFB42 and UL9 in human embryonic kidney the UL9 protein is located predominantly in the nucleus (13), it (293T) cells led to a significant decrease in the level of UL9 protein. was important to determine the mechanism that permits their We have now found that HSV-1 infection promotes the shuttling interaction. We report here that HSV-1 infection promotes the of NFB42 between the cytosol and the nucleus in both 293T cells shuttling of NFB42 between the cytosol and the nucleus in both and primary hippocampal neurons, permitting NFB42 to bind to the 293T cells and in primary hippocampal neurons, and that NFB42 phosphorylated UL9 protein, which is localized in the nucleus.