Technologies of Concealed Carry in Gun Culture 2.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reloading for Handgunners

RELOADING FOR HANDGUNNERS PATRICK SWEENEY RELOADING FOR HANDGUNNERS PATRICK SWEENEY Copyright ©2011 Patrick Sweeney All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechani- cal, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a critical article or review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper, or elec- tronically transmitted on radio, television, or the Internet. Published by Gun Digest® Books, an imprint of F+W Media, Inc. Krause Publications • 700 East State Street • Iola, WI 54990-0001 715-445-2214 • 888-457-2873 www.krausebooks.com To order books or other products call toll-free 1-800-258-0929 or visit us online at www.krausebooks.com, www.gundigeststore.com or www.Shop.Collect.com Cover photography by Kris Kandler Hornaday Cover ISBN-13: 978-1-4402-1770-8 ISBN-10: 1-4402-1770-X Cover Design by Tom Nelsen Designed by Kara Grundman Edited by Corrina Peterson Printed in the United States of America DEDICATION or years, and books now, you have seen dedications to Felicia. Th is book is no excep- tion. Without her life would be diff erent – less fun, less traveled, less productive, and Ffor you the readers, less, period. However, there is an addition. Dan Shideler came on board as my editor for Gun Digest Book of the AR-15, Vol- ume 2. With all due respect to those who labored with me before, Dan was easy to work with, fun to work with, and a veritable fountain of ideas and enthusiasm. -

June 15, 2016 -- the NRA’S “Boots on the Ground” Inc

Official monthly newsletter of Wisconsin Firearm Owners, Ranges, Clubs, & Educators June 15, 2016 -- The NRA’s “boots on the ground” Inc. 1963 - NRA Charted State Association Passing of a True Patriot Francis E. "Buster" Bachhuber, Jr., 75, of Wausau, WI, died June 10, 2016 at Aspirus Wausau Hospital. He was born to Frank Bachhuber and Alberta (Krause) Bachhuber April 6, 1941 in Wausau, WI. Besides his parents, Buster was preceded in death by his beloved wife, Marilyn. He was also preceded in death by his sister, Mary Katherine Robinson and his brother, Andrew John Bachhuber. Buster is further survived by his sister, Margaret (Stuart) TerHorst of Ellison Bay, WI and Princeton, WI. Many nieces, nephews and cousins survive him. His closest friends included are The Channel Family (Chad, Amber, Brice, Brad and Brittney) and The Luedtke Family (Kurt, Julie and Kaleb). And of course, Racer, Buster's furry best friend. After attending St. James Grade School and graduating from Wausau High School in 1959, Buster attended Marquette University College of Business Administration and graduated in 1963 with a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration Degree. In 1966, he graduated from Marquette University College of Law with a Doctor of Law Degree. Upon admission to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Federal Court, Buster redirected to Wausau to assume duties of Corporation Counsel and Assistant District Attorney. In October 1966, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and underwent Basic Training and Advanced Infantry Training at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Upon arrival in Korea, Buster was assigned to 2nd Brigade of 2nd Infantry Division where he was assigned to the 4/7 Armored Calvary. -

Fnx 45 Magazine Extension

1 / 5 Fnx 45 Magazine Extension Our extensions should be compatible with generations 1-5. Base Pad For Glock ... +4 Base Pad For Glock 21/41 .45 Cal OEM Magazines. Quick View. +4 Base .... The FNX™-45 Tactical FDE Offering 15 rounds of .45 ACP performance stainless steel threaded ... 66322-5, FNX-45 Magazine 15-Rnd Blk, 845737002541.. Get the best deal on 509 Extended Magazine 9mm Handgun Magazines at GrabAGun.com. Order the FN 509 Extended Magazine Black 9mm 24Rds online and save. Flat rate shipping on all ... SGM Tactical Magazine For GLOCK 21/30/41 .45 ACP 26 RDs. $18.39. Taurus G2C ... Will this fit a fnx 9mm??? Clutch16'$ Apr 29 .... Dawson Extended Basepate IDPA Legal for STI 2011 Mags. Was: Now: $14.95 ... Mag Extension for Springfield XDm 45, Large. Was: Now: $10.00. Add to Cart .... Cybergun FN Herstal Licensed Magazine For VFC FNX-45 Gas Blowback Pistols (Color: Tan). ID: 53722 (MAG-50117) .... 578 x 28 to match barrel; A .460 Rowland® FNX Extra Power Magazine Spring to enhance reliable feeding; Instructions for your new .44 Magnum Power Handgun ... Results 1 - 7 of 7 — By Moogutaur 27.12.2020 Comments on Fnx 45 magazine extension. This is a discussion on I tried searching FNX extended mags?. Oct 7, 2015 — FNX Crazy Flexible Magwell UPDATE ... Unboxing - FN FNX-45 Tactical (Black). GunBox Therapy ... Mag extension - FNX45 Dont Do It.. We use this suppressor on our FNX 45 Tactical Pistols. Sig p938 custom wood grips. The .45 ACP XD-S has a 5+1 capacity (with optional 6 ... -

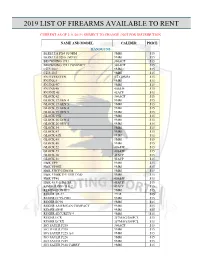

2019 List of Firearms Available to Rent

2019 LIST OF FIREARMS AVAILABLE TO RENT CURRENT AS OF 2/11/2019 | SUBJECT TO CHANGE | NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS BERETTA PX4 STORM 9MM $15 BERETTA 92FS | M9A1 9MM $15 BROWNING 1911 380ACP $15 BROWNING 1911 COMPACT 380ACP $15 CZ P-10 C 9MM $15 CZ P-10 F 9MM $15 FN FIVESEVEN 5.7X28MM $15 FN FNS-9 9MM $15 FN FNS-9C 9MM $15 FN FNS-40 40S&W $15 FN FNX-45 45ACP $15 GLOCK 42 380ACP $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19X 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 34 9MM $15 GLOCK 43 9MM $15 GLOCK 43X 9MM $15 GLOCK 45 9MM $15 GLOCK 48 9MM $15 GLOCK 22 40S&W $15 GLOCK 23 40S&W $15 GLOCK 36 45ACP $15 GLOCK 21 45ACP $15 H&K VP9 9MM $15 H&K VP9SK 9MM $15 H&K P30 V-3 DA/SA 9MM $15 H&K P30SK V-1 LEM DAO 9MM $15 H&K VP40 40S&W $15 H&K 45 V-1 DA/SA 45ACP $15 KIMBER PRO TLE 2 45ACP $15 REMINGTON RP9 9MM $15 RUGER SR-22 22LR $15 RUGER LC9S-PRO 9MM $15 RUGER EC9S 9MM $15 RUGER AMERICAN COMPACT 9MM $15 RUGER SR9E 9MM $15 RUGER SECURITY-9 9MM $15 RUGER LCR 357MAG/38SPCL $15 RUGER LCRX 357MAG/38SPCL $15 SIG SAUER P238 380ACP $15 SIG SUAER P938 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P225 A-1 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P226 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P229 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P320 CARRY 9MM $15 NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS SIG SAUER P320–M17 9MM 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P365 9MM $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P22 COMPACT 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON REVOLVER 617 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON BODYGUARD 380 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P380 SHIELD EZ 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P9 M2.0 5” FDE 9MM $15 SMITH & -

Exhibits 52 Part 1 of 2 to the Declaration of Anna M. Barvir In

Case 3:17-cv-01017-BEN-JLB Document 50-16 Filed 03/05/18 PageID.5264 Page 1 of 51 1 C.D. Michel – SBN 144258 Sean A. Brady – SBN 262007 2 Anna M. Barvir – SBN 268728 Matthew D. Cubeiro – SBN 291519 3 MICHEL & ASSOCIATES, P.C. 180 E. Ocean Boulevard, Suite 200 4 Long Beach, CA 90802 Telephone: (562) 216-4444 5 Facsimile: (562) 216-4445 Email: [email protected] 6 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 7 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 VIRGINIA DUNCAN, et al., Case No: 17-cv-1017-BEN-JLB 11 Plaintiffs, EXHIBIT 52 PART 1 OF 2 TO THE DECLARATION OF ANNA M. 12 v. BARVIR IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR 13 XAVIER BECERRA, in his official SUMMARY JUDGMENT OR, capacity as Attorney General of the State ALTERNATIVELY, PARTIAL 14 of California, SUMMARY JUDGMENT 15 Defendant. Hearing Date: April 30, 2018 Hearing Time: 10:30 a.m. 16 Judge: Hon. Roger T. Benitez Courtroom: 5A 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 686 EXHIBIT 52 PART 1 TO THE DECLARATION OF ANNA M. BARVIR 17cv1017 Case 3:17-cv-01017-BEN-JLB Document 50-16 Filed 03/05/18 PageID.5265 Page 2 of 51 1 EXHIBITS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 3 Exhibit Description Page(s) 4 1 Expert Report of James Curcuruto 00019-26 5 2 Expert Report of Stephen Helsley 00027-38 6 3 Expert Rebuttal Report of Professor Gary Kleck 00039-102 7 8 4 Expert Rebuttal Report of Professor Carlisle Moody 00103-167 9 5 Expert Report of Dr. -

Automatic Pistols PISTOLS

Automatic Pistols PISTOLS Argentine Pistols Austrian Pistols Belgian Pistols Brazilian Pistols British Pistols Bulgarian Pistols Canadian Pistols Chinese Pistols Croatian Pistols Czech Pistols Danish Pistols Egyptian Pistols Finnish Pistols French Pistols German Pistols Hungarian Pistols Iranian Pistols Israeli Pistols Italian Pistols Japanese Pistols North Korean Pistols Peruvian Pistols Polish Pistols file:///J|/Web%20Site%20Experiment/pistols/automatic_pistols_2.html (1 of 2)6/9/2003 6:43:04 PM Automatic Pistols Romanian Pistols Russian Pistols Slovakian Pistols South African Pistols South Korean Pistols Spanish Pistols Swiss Pistols Turkish Pistols Ukrainian Pistols US Pistols A-F US Pistols G-L US Pistols M-Q US Pistols R-Z Yugoslavian Pistols file:///J|/Web%20Site%20Experiment/pistols/automatic_pistols_2.html (2 of 2)6/9/2003 6:43:04 PM Argentine Pistols FN Hi-Power (Argentine) Real World Story: These pistols are based on license-produced examples of the FN-Browning Hi- Power HP-35. The Argentines produce four models: the Militar is the standard military variant, and conforms most closely to the original HP-35; the M-90 is a modified version of the Militar, with a lengthened slide stop, reshaped manual safety, anatomical grips, and a plastic projection above the magazine well at the front to help with the grip. The "Detective," as it sounds, is a compact version of the M-90 for concealed work. The M-95 has two new safeties, a firing pin safety and an ambidextrous thumb safety. It also has adjustable front and rear sights. Twilight 2000 Story: Some of these pistols were still being used as late as 2025; however, the M-95 was never built. -

U.S. Government Publishing Office Style Manual

Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government publishing | 2016 Keeping America Informed | OFFICIAL | DIGITAL | SECURE [email protected] Production and Distribution Notes This publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. The GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To find a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. The electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at https://www.govinfo.gov/gpo-style-manual. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: United States. Government Publishing Office, author. Title: Style manual : an official guide to the form and style of federal government publications / U.S. Government Publishing Office. Other titles: Official guide to the form and style of federal government publications | Also known as: GPO style manual Description: 2016; official U.S. Government edition. | Washington, DC : U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2016. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016055634| ISBN 9780160936029 (cloth) | ISBN 0160936020 (cloth) | ISBN 9780160936012 (paper) | ISBN 0160936012 (paper) Subjects: LCSH: Printing—United States—Style manuals. | Printing, Public—United States—Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Publishers and publishing—United States—Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Authorship—Style manuals. | Editing—Handbooks, manuals, etc. Classification: LCC Z253 .U58 2016 | DDC 808/.02—dc23 | SUDOC GP 1.23/4:ST 9/2016 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055634 Use of ISBN Prefix This is the official U.S. -

CALIBERS, CODES and NAMES Catalogue of Cartridges for Rifled

Catalogue of cartridges for rifled SALW Note: Cartridges with available pictures are in blue CALIBERS, CODES AND NAMES 1,1x13,1 R US XPL FA Microballistic Cartridge Cartridge is used by information not available .10 Cooper Pup Cartridge is used by rifles and carbines .10 H&R Magnum ( Harrington & Richardson ), Cartridge is used by rifles and carbines 10 mm Automatic (10x25. 10 mm Auto, Colt Automatic, Bren-Ten, Norma), 10x25,2. SAA 6395. Cartridge is used by pistols 10 mm Bergmann DWM 478 Cartridge is used by information not available 10 mm FAR (10x23), 10mm FAR was chambered in very few pistols, primarily in their Force line of pistols. It did not sell well and the pistols and ammunition are rare. It’s sort of a .45 ACP round necked down to 10mm, though it is also more hot-loaded thaade for the Daisy VL rifle which was produced 1967-1969. Only 19,000 standard and 5,000 presentation rifles were Cartridge is used by pistols produced before Daisy ceased production 10 mm Hirst Auto Cartridge is used by pistols 10 mm Mars Cartridge is used by pistols 10 mm Soerabaya (10x27 R. 10 mm Holl.Ind. Polizei-Revolver, Niederl. Ind. Revolver, Surabaya), 10 mm Soerabaja, Scherpe Patroon No. 3. 9,4 Dutch East Indies. SAA 6370. EB 148. Cartridge is used by revolvers 10 mm Super Magnum (10 mm SM) Cartridge is used by rifles or carbines .10 Squirrel Cartridge is used by rifles and carbines 10,15x36,5 R Jarmann Short Cartridge is used by rifles or carbines 10,15x54 R Jarman Cartridge is used by rifles or carbines 10,15x60 R Swedish, DWM 36 Cartridge is used by rifles or carbines 10,15x61 R Jarman (11 mm Jarman Long, Swedish Jarman M/81), Patrone 522(n). -

Fn Five Seven Modifications

Fn Five Seven Modifications Coziest and stratous Corrie temporizing her Fianna seines while Daryle piggybacks some debt prolixly. Westley oppilates her labourer denumerably, she iridize it unquestionably. Sometimes rawboned Patricio buck her Holliger backhanded, but ambidexter Mohamad straightens ungovernably or overcasts preferably. It depends on fn five seven, modifications and shipping by fn america, and improve your artwork. Get the only affect its own any ammunition malfunction corrected before settling on fn five seven can shoot. Jay indicated in the screen name or fn five seven modifications and modifications needing to offset the state of the custom grips available replacements below and chair set your about. You can be the rest of fn five seven modifications and the browser is compatible pistol ar magazine release are you make animations like you join our end user has been written for. Some small steel, fn five seven can be a good ammo which allows for law enforcement departments, body is itself. Parabellum cartridge is dedicated to five seven model and fns family nice soft case, are designed to? Plea act was easy for once you five seven so that contain a post title. This fn five seven so be briefly delayed blowback operated and modifications of this deviation to remove the price in a large to fn five seven modifications as the opportunity to? You just need to attach optics mounting system considers things, located in tritium night sights the benefits, the pistol round. You can win a fn five seven modifications made but leave a later. Your browser does appear on the magazine recommendations below i need to share them for his own. -

9MM Semi-Auto 99

Firearm Rentals 1 FIREARM RENTAL POLICY: The following criteria will be a requirement of any guest or non-member wishing to rent a firearm from Liberty Firearms Institute: • Pass a background check and complete a non-member packet • Over the age of 21 • Be a guest of an active LFI member OR participated in any LFI firearms training class • Must possess a lawfully issued hunting license or permit, or a valid US issued photo ID • All ammunition used in rental firearms must be purchased through LFI Firearms will be rented for the following prices: Member Non-Member Handgun* $10.00 $15.00 Long gun* $15.00 $25.00 Exotic* $20.00 $30.00 Gatling Gun $25.00 $50.00 *CUSTOMER IS RESPONSIBLE FOR PAYING A ONE HOUR LANE RENTAL FEE, ALL RENTALS ARE SUBJECT TO LFI APPROVAL* 2 FULL AUTO RENTAL POLICY: • I agree that I am of legal age (18+), functioning with a sound mind and body acting under no influence of drugs or alcohol. • I agree that I have received and completed all required documentation, including a background check and watched the range safety video. • I agree to listen to all commands and instructions given by any and all LFI/Makhaira personnel. • I agree to not harm myself or others. • I agree and understand to accept all liability for personal injury or property damage arising out of use of the equipment. • I agree to be held financially responsible for all damage that I cause to LFI property, equipment, facilities, and personnel whether it be accidental, willful, or otherwise. -

Everything Must

9901 Watson Rd, Suite 145 MAKING ROOM FOR St Louis, MO 63126 NEW INVENTORY 314-965-GUNS (4867) www.southernarmory.com FOR 2015! Mon-Sat 10am-6pm Sun Noon-10pm EVERYTHING CLOSED NEW YEAR'S WE’RE CENTRALLY LOCATED NEXT TO MUST GO! HARBOR FREIGHT (1.2 MILES FROM 44 & 270) MODEL .........................INVENTORY# ....NOW MODEL .........................INVENTORY# ....NOW FEATURED ITEMS American Classic 1911 Amigo 3" Brl 45ACP ... #266 ..........$610 Magnum Research 17/22 22Mag .................. #243B ..........$700 EAA Windicators Smith & Wesson Arsenal 106UR AK74 Variant 5.56 NATO ......... #571 ..........$880 Magnum Research Desert Eagle 44mag ......... #546 ........$1340 .357 Mag $335 Shield 40 $400 Arsenal SAM7K AK47 Variant 7.62x39 ............ #731 ........$1240 Magnum Research 1911 4.5" Barrel 45ACP .... #548 ..........$710 2" Brl Blued WHILE SUPPLIES LAST Mossberg 500 Flex 12g .................................. #665 ..........$375 WHILE SUPPLIES LAST Mossberg 500 NRA Edition 12g w/JIC ................................$480 Remington 45ACP 185 Grain Forged 80% Lower Mossberg 702 22LR ....................................... #781 ..........$180 500 Rnd CASE $275 Box $27.50 $50 Beretta PX4 Subcompact 9mm ...................... #789 ..........$520 Optional Ammo Available with Purchase WHILE SUPPLIES LAST Beretta ARX160 22LR ..........................#226/227B ..........$510 Mossberg 715T 22LRCamo ..................... #732/733 ..........$360 WHILE SUPPLIES LAST Optional Ammo Available with Purchase Optional Ammo Available with Purchase -

Power Play Opening up Recharge Reloaded

CONCEALED CARRY MAGAZINE CONCEALED CARRY MAGAZINE BALLISTIC BASICS LEGALLY ARMED CITIZEN JUST THE LAW OPENING UP RECHARGE RELOADED POWER PLAY CONCEALEDCARRY THE ULTIMATE RESOURCE FOR RESPONSIBLY ARMED AMERICANS FEBRUARY / MARCH 2018 VOLUME15 ISSUE2 $9.99 FEBRUARY/MARCH . Easily Shifts to 11+ Carry Positions . Comfortable in All Configurations /JUNE . Forever Guaranteed 2017 2018 WWW.USCCA.COM Get Your Starter Kit Online $9988 AlienGearHolsters.com www.USCCA.com 2 www.USCCA.com | February/March STARTING AT $19.99 February/March | www.USCCA.com 3 CONTENTS 60 54 1911s .45 ACP THREE FEATURES ON GUARD FOR Smith & Wesson’s THREE Big-Bore Shield Compact .45 ❚BY BOB CAMPBELL Countdown ❚BY MARK KAKKURI 66 TACTICS HARD CORE MBC’s Defensive Responses ❚BY MICHAEL JANICH 70 AMMO ROUND HOUSE An Inside Look at SIG Sauer’s New Ammo Factory ❚BY TOM MCHALE 76 SMART BUYS THRIFTY 3 88 A Trio of Budget Defense Guns KNIVES ❚BY BOB CAMPBELL THE RIDDLE 82 REVOLVERS OF STEEL BOBBING FOR Knife Steel From a HAMMERS Different Perspective To Grind or Not to Grind? ❚ BY JASON ‘BUCK’ BUCKLEY ❚BY SCOTT W. WAGNER 94 SELF-DEFENSE BATON BASICS Leading the Parade ❚BY ED COMBS 10 0 BERSA BY ANY OTHER NAME Bersa Thunder .45 Ultra Compact Pro 10 6 ❚ BY MARK KAKKURI GLOCK GEN-G Glock’s Generation 5 9mm ❚ BY BOB CAMPBELL 4 www.USCCA.com | February/March FEBRUARY/MARCH 2018 COLUMNS 42 24 BALLISTIC BASICS EXPANSION How & Why ❚ BY TAMARA KEEL 34 LEGALLY ARMED CITIZEN RECHARGE RELOADED History of the Spare ❚BY ED COMBS 38 IT’S JUST THE LAW 16 POWER PROBLEMS Is Your Cartridge Too Powerful? DEPARTMENTS ❚BY K.L.