Home Team Robert F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

Big League Expansion

WEDNESDAY, MAY 1, 1961 With South High winning its fourth straight shutout and North losing to Mira Costa, 4-2, the two Torrance schools are tied for the Bay League baseball lead with 11-3 records. Big League Mira Costa scored four runs in the first inning to beat the Saxons. Costa has a|' 4-8 record. Expansion Dick Foulk, who went eight innings to edge Mira Costa, Smith ...........ir...........11 1-0, a week ago, came back Hawthorn* ......10 Veteran baseball front office executive Bill Veeck' Redondo ........ 6 Monday for an 11-0 whitewash 8»nto Monica , unveiling his proposal for a sweeping realignment of' of Redondo. Dennis RectorlMir* o»u....... 4 the major leagues, submits a plan that place the New hurled two innings of the win. In«"1""x><Vond.y'. ' " Mlr» CosU 4. North 1 York Yankees and New York Mets together in one divi The Spartans got their first South H. RndondoO sion, the Chicago White "Sox and Chicago Cubs together two runs in the first frame Hawthorn* 9, B*nU MnnJ<m 4 Today'* damn In another, and the Los Angeles Dodgers, Anahcim and picked up five more in South «t 8*1**. Monlc* the third. Infrlewood at North Angels, San Francisco Giants and Oakland Athlet'cs in Steve Shrader cleaned the yet another division composed entirely of West Ccast bases with a triple as part of teams. the 5-run spree. Elaborating on his ideas in an article in the current MikeHrehor'and Brent Bar- Triple by ron both had two hits for the Issue of Sport Magazine, Veeck proposes the following Spartans. -

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

After One of the Worst Starts Ever to a Baseball Career, John J. Mcgraw Became a Sports Legend As a Champion Player and Manager in the Early 20Th Century

After one of the worst starts ever to a baseball career, John J. McGraw became a sports legend as a champion player and manager in the early 20th century. John Joseph McGraw was born in Truxton, Cortland County, on April 7, 1873. His relationship with his father grew strained after John’s mother and four siblings died during an epidemic in the winter of 1884-5. John left home while still in school, where he starred on the baseball team. Obsessed with the game, he spent the money he earned from odd jobs on baseball equipment and rulebooks. In 1890, John decided to make a career of baseball. He started out earning $5 a game for the Truxton Grays. When the Grays’ manager took over the Olean franchise of the New York-Penn League, John became his third baseman. He committed eight Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction errors in his rst game with Olean. After six games, he number LC-DIG-ggbain-34093] was cut from the team. McGraw kept trying. He played shortstop for Wellsville in the Western New York League and showed skill as a hitter and baserunner. After the 1890 season, McGraw joined the American All-Stars, a team that toured the southern states and Cuba during the winter. In 1891, a team of All-Stars and Florida players challenged the Cleveland Spiders of the American Association, one of the era’s two major leagues, to a spring-training exhibition game. Cleveland won, but McGraw got three hits in ve at-bats. Coverage of the game in The Sporting News inspired several teams to offer McGraw contracts. -

Home Team: the Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants Online

9mges (Ebook free) Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants Online [9mges.ebook] Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants Pdf Free Robert F. Garratt DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #146993 in Books NEBRASKA 2017-04-01Original language:English 8.88 x 1.07 x 6.25l, .0 #File Name: 080328683X264 pagesNEBRASKA | File size: 27.Mb Robert F. Garratt : Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A GRAND SLAMBy alain robertIf you are looking for a coffee table book filled with color pictures,this book is not for you.However,if you want to know about the team's turbulent sixty year history and those legendary CANDLESTICK stories that became a trademark of the city, this book will please you.There are also anecdotes about the team's early stars like MAYS,MARICHAL,CEPEDA and WILLIE THE STRETCHER McCOVEY.Well done from beginning to end.Any true baseball fan should enjoy.In case you don't remember,THE BEATLES's last concert was at CANDLESTICK in 1966.3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Giant Fans Will Love This BookBy Dominic CarboniThe author did an outstanding job describing the Giant's move from New York to their present home. His story brought back fond memories of us teenagers sneaking into Seals stadium to watch the new home team. -

San Francisco Giants

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2016 END OF SEASON NOTES 24 Willie Mays Plaza • San Francisco, CA 94107 • Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com • sfgigantes.com • sfgiantspressbox.com • @SFGiants • @SFGigantes • @SFG_Stats THE GIANTS: Finished the 2016 campaign (59th in San Francisco and 134th GIANTS BY THE NUMBERS overall) with a record of 87-75 (.537), good for second place in the National NOTE 2016 League West, 4.0 games behind the first-place Los Angeles Dodgers...the 2016 Series Record .............. 23-20-9 season marked the 10th time that the Dodgers and Giants finished in first and Series Record, home ..........13-7-6 second place (in either order) in the NL West...they also did so in 1971, 1994 Series Record, road ..........10-13-3 (strike-shortened season), 1997, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2012, 2014 and 2015. Series Openers ...............24-28 Series Finales ................29-23 OCTOBER BASEBALL: San Francisco advanced to the postseason for the Monday ...................... 7-10 fourth time in the last sevens seasons and for the 26th time in franchise history Tuesday ....................13-12 (since 1900), tied with the A's for the fourth-most appearances all-time behind Wednesday ..................10-15 the Yankees (52), Dodgers (30) and Cardinals (28)...it was the 12th postseason Thursday ....................12-5 appearance in SF-era history (since 1958). Friday ......................14-12 Saturday .....................17-9 Sunday .....................14-12 WILD CARD NOTES: The Giants and Mets faced one another in the one-game April .......................12-13 wild-card playoff, which was added to the MLB postseason in 2012...it was the May .........................21-8 second time the Giants played in this one-game playoff and the second time that June ...................... -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

City 'Scapes Online

qjbsS [Free read ebook] City 'Scapes Online [qjbsS.ebook] City 'Scapes Pdf Free Craig Carrozzi audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3736193 in eBooks 2012-08-10 2012-08-10File Name: B008WV8VNW | File size: 68.Mb Craig Carrozzi : City 'Scapes before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised City 'Scapes: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Woulda Coulda ShouldaBy Howlin' CoyoteThe San Francisco Giants had the best record in Major League Baseball in the 1960s--but they failed to win a World Series and won only one National League Pennant after a hectic three game playoff with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1962. Yet, despite the failures, this was aruguably one of the most exciting teams of that or any era and packed in the fans all over the National League. Hall of Fame stars such as Willie Mays, Willie McCovery, and Orlando Cepeda slammed baseballs off and over fences all over the league. Great pitchers such as Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry made their mark, Marichal with one of the most unusual pitching motions in baseball history and Gaylord Perry with his infamous spitball.Yet, "City 'Scapes" isn't your usual baseball book, filled with wooden facts and relying on the oft-times predjudiced and spin-oriented pronouncements of former major league players and executives. It is a story--faction if you will--that recreates the excitement of an actual game and era, Giants vs. Cincinnati Reds in 1961, as told through the eyes of a diverse group of fans with loyalties in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Cincinnati, and who battle by virtue of their opinions as hard as the players on the field while the game is in progress. -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Braves.com Braves' Top 5 center fielders: Bowman's take By Mark Bowman No one loves a good debate quite like baseball fans, and with that in mind, we asked each of our beat reporters to rank the top five players by position in the history of their franchise, based on their career while playing for that club. These rankings are for fun and debate purposes only … if you don’t agree with the order, participate in the Twitter poll to vote for your favorite at this position. Here is Mark Bowman’s ranking of the top 5 center fielders in Braves history. Next week: Right fielders. 1. Andruw Jones, 1996-2007 Key fact: Stands with Roberto Clemente, Willie Mays and Ichiro Suzuki as the only outfielders to win 10 consecutive Gold Glove Awards The 60.9 bWAR (Baseball Reference’s WAR model) Andruw Jones produced during his 11 full seasons (1997-2007) with Atlanta ranked third in the Majors, trailing only Alex Rodriguez (85.7) and Barry Bonds (79.2). Chipper Jones was fourth at 58.9. Within this span, the Braves center fielder led all Major Leaguers with a 26.7 Defensive bWAR. Hall of Fame catcher Ivan Rodriguez ranked second with 16.5. The next closest outfielder was Mike Cameron (9.6). Along with establishing himself as one of the greatest defensive outfielders baseball has ever seen during his time with Atlanta, Jones became one of the best power hitters in Braves history. He ranks fourth in franchise history with 368 homers, and he set the club’s single-season record with 51 homers in 2005. -

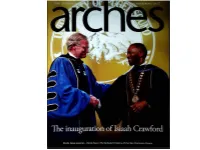

Spring 2017 Arches 5 WS V' : •• Mm

1 a farewell This will be the last issue o/Arches produced by the editorial team of Chuck Luce and Cathy Tollefton. On the cover: President EmeritusThomas transfers the college medal to President Crawford. Conference Women s Basketball Tournament versus Lewis & Clark. After being behind nearly the whole —. game and down by 10 with 3:41 left in the fourth |P^' quarter, the Loggers start chipping away at the lead Visit' and tie the score with a minute to play. On their next possession Jamie Lange '19 gets the ball under the . -oJ hoop, puts it up, and misses. She grabs the rebound, Her second try also misses, but she again gets the : rebound. A third attempt, too, bounces around the rim and out. For the fourth time, Jamie hauls down the rebound. With 10 seconds remaining and two defenders all over her, she muscles up the game winning layup. The crowd, as they say, goes wild. RITE OF SPRING March 18: The annual Puget Sound Women's League flea market fills the field house with bargain-hunting North End neighbors as it has every year since 1968 All proceeds go to student scholarships. photojournal A POST-ELECTRIC PLAY March 4: Associate Professor and Chair of Theatre Arts Sara Freeman '95 directs Anne Washburn's hit play, Mr. Burns, about six people who gather around a fire after a nationwide nuclear plant disaster that has destroyed the country and its electric grid. For comfort they turn to one thing they share: recollections of The Simpsons television series. The incredible costumes and masks you see here were designed by Mishka Navarre, the college's costumer and costume shop supervisor. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

2019 Topps Diamond Icons BB Checklist

AUTOGRAPH AUTOGRAPH CARDS AC-AD Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® AC-AJU Aaron Judge New York Yankees® AC-AK Al Kaline Detroit Tigers® AC-AP Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® AC-ARI Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® AC-ARO Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® AC-BG Bob Gibson St. Louis Cardinals® AC-BJ Bo Jackson Kansas City Royals® AC-BL Barry Larkin Cincinnati Reds® AC-CF Carlton Fisk Boston Red Sox® AC-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ AC-CK Corey Kluber Cleveland Indians® AC-CKE Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® AC-CR Cal Ripken Jr. Baltimore Orioles® AC-CS Chris Sale Boston Red Sox® AC-DE Dennis Eckersley Oakland Athletics™ AC-DMA Don Mattingly New York Yankees® AC-DMU Dale Murphy Atlanta Braves™ AC-DO David Ortiz Boston Red Sox® AC-DP Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® AC-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® Rookie AC-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ AC-FF Freddie Freeman Atlanta Braves™ AC-FL Francisco Lindor Cleveland Indians® AC-FM Fred McGriff Atlanta Braves™ AC-FT Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® AC-FTJ Fernando Tatis Jr. San Diego Padres™ Rookie AC-GSP George Springer Houston Astros® AC-HA Hank Aaron Atlanta Braves™ AC-HM Hideki Matsui New York Yankees® AC-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ AC-JA Jose Altuve Houston Astros® AC-JBA Jeff Bagwell Houston Astros® AC-JBE Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® AC-JC Jose Canseco Oakland Athletics™ AC-JD Jacob deGrom New York Mets® AC-JDA Johnny Damon Boston Red Sox® AC-JM Juan Marichal San Francisco Giants® AC-JP Jorge Posada New York Yankees® AC-JS John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ AC-JSO Juan Soto Washington Nationals® AC-JV Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® AC-JVA Jason Varitek Boston Red Sox® AC-KB Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® AC-KS Kyle Schwarber Chicago Cubs® AC-KT Kyle Tucker Houston Astros® Rookie AC-LB Lou Brock St.