Making Meaning Together: Information, Rumor, and Propaganda in British Fiction of the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

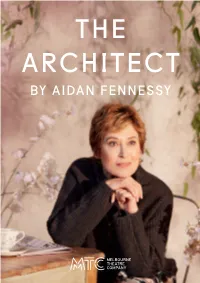

THE ARCHITECT by AIDAN FENNESSY Welcome

THE ARCHITECT BY AIDAN FENNESSY Welcome The Architect is an example of the profound role theatre plays in helping us make sense of life and the emotional challenges we encounter as human beings. Night after night in theatres around the world, audiences come together to experience, be moved by, discuss, and contemplate the stories playing out on stage. More often than not, these stories reflect the goings on of the world around us and leave us with greater understanding and perspective. In this world premiere, Australian work, Aidan Fennessy details the complexity of relationships with empathy and honesty through a story that resonates with us all. In the hands of Director Peter Houghton, it has come to life beautifully. Australian plays and new commissions are essential to the work we do at MTC and it is incredibly pleasing to see more and more of them on our stages, and to see them met with resounding enthusiasm from our audiences. Our recently announced 2019 Season features six brilliant Australian plays that range from beloved classics like Storm Boy to recent hit shows such as Black is the New White and brand new works including the first NEXT STAGE commission to be produced, Golden Shield. The full season is now available for subscription so if you haven’t yet had a look, head online to mtc.com.au/2019 and get your booking in. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. -

H. G. Wells Science and Philosophy the Time

H. G. Wells Science and Philosophy Friday 28 September Imperial College, London Saturday 29 September 2007 Library, Conway Hall, Red Lion Square, London Programme ____________________________________________________________________________ Friday 28 September 2007 – Room 116, Electrical Engineering Building, Imperial College, South Kensington, London 2.00-2.25 Arrivals 2.25-2.30 Welcome (Dr Steven McLean) 2.30-3.30 Papers: Panel 1: - Science in the Early Wells Chair: Dr Steven McLean (Nottingham Trent University) Dr Dan Smith (University of London) ‘Materiality and Utopia: The presence of scientific and philosophical themes in The Time Machine’ Matthew Taunton (London Consortium) ‘Wells and the New Science of Town Planning’ 3.30-4.00 Refreshments 4.00-5.00 Plenary: Stephen Baxter (Vice-President, H. G. Wells Society) ‘The War of the Worlds: A Controlling Metaphor for the 20th Century’ Saturday 29 September 2007 - Library. Conway Hall, Red Lion Square, London 10.30-10.55 Arrivals 10.55-11.00 Welcome (Mark Egerton, Hon. General Secretary, H. G. Wells Society) 11.00-12.00 Papers: Panel 2: - Education, Science and the Future Chair: Professor Patrick Parrinder (University of Reading) Professor John Huntington (University of Illinois, Chicago) ‘Wells, Education, and the Idea of Literature’ Anurag Jain (Queen Mary, London) ‘From Noble Lies to the War of Ideas: The Influence of Plato on Wells’s Utopianism and Propaganda’ 12.00-1.30 Lunch (Please note that, although coffee and biscuits are freely available, lunch is not included in this year’s conference fee. However, there are a number of local eateries within the vicinity). 1.30- 2.30 Papers: Panel 3: Wells, Modernism and Reality Chair: Professor Bernard Loing (Chair, H. -

War and the Future

War and the Future H. G. Wells War and the Future Table of Contents War and the Future..................................................................................................................................................1 H. G. Wells.....................................................................................................................................................1 THE PASSING OF THE EFFIGY................................................................................................................1 THE WAR IN ITALY.................................................................................................................................10 I. THE ISONZO FRONT.............................................................................................................................10 II. THE MOUNTAIN WAR........................................................................................................................13 III. BEHIND THE FRONT..........................................................................................................................16 THE WESTERN WAR (SEPTEMBER, 1916)...........................................................................................21 I. RUINS......................................................................................................................................................21 II. THE GRADES OF WAR........................................................................................................................25 III. THE WAR -

Thorstein Veblen and HG Wells

020 brant (453-476) 1/30/08 9:14 AM Page 453 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks PATRICK BRANTLINGER AND RICHARD HIGGINS Waste and Value: Thorstein Veblen and H. G. Wells Trashmass, trashmosh. On a large enough scale, trashmos. And— of course—macrotrashm! . Really, just think of it, macrotrashm! Stanislaw Lem, The Furturological Congress INTRODUCING FILTH: DIRT, DISGUST, and Modern Life, William Cohen declares: “polluting or filthy objects” can “become conceivably productive, the discarded sources in which riches may lie.”1 “Riches,” though, have often been construed as “waste.” The reversibility of the poles—wealth and waste, waste and wealth— became especially apparent with the advent of a so-called consumer society dur- ing the latter half of the nineteenth century. A number of the first analysts of that economistic way of understanding modernity, including Thorstein Veblen and H. G. Wells, made this reversibility central to their ideas.2 But such reversibility has a much longer history, involving a general shift from economic and social the- ories that seek to make clear distinctions between wealth and waste to modern ones where the distinctions blur, as in Veblen and Wells; in some versions of post- modernism the distinctions dissolve altogether. Cohen also writes: “As it breaches subject/object distinctions . filth . covers two radically different imaginary categories, which I designate polluting and reusable. The former—filth proper—is wholly unregenerate.”3 Given the reversibility of the poles (and various modes of the scrambling or hybridization of values), what is the meaning of “filth proper”? Proper filth? Filthy property? Is there any filth that is not potentially “reusable” and, hence, valuable? Shit is valu- able as fertilizer, and so on. -

HG Wells and Dystopian Science Fiction by Gareth Davies-Morris

The Sleeper Stories: H. G. Wells and Dystopian Science Fiction by Gareth Davies-Morris • Project (book) timeline, Fall 2017 • Wells biography • Definitions: SF, structuralism, dystopia • “Days to Come” (models phys. opps.) • “Dream of Arm.” (models int. opps.) • When the Sleeper Wakes • Intertextuality: Sleeper vs. Zemiatin’s We • Chapter excerpt Herbert George Wells (1866-1946) The legendary Frank R. Paul rendered several H. G. Wells narratives as covers for Hugo Gernsback’s influential pulp magazine Amazing Stories, which reprinted many of Wells’s early SF works. Clockwise from top: “The Crystal Egg” (1926), “In the Abyss” (1926), The War of the Worlds (1927), and When the Sleeper Wakes (1928) Frank R. Paul, cover paintings for Amazing Stories, 1926-1928. “Socialism & the Irrational” -- Wells-Shaw Conference, London School of Economics Fall 2017 Keynote: Michael Cox Sci-Fi artwork exhibit at the Royal Albert Hall! Fabian stained -glass window in LSE “Pray devoutly, hammer stoutly” Gareth with Professor Patrick Parrinder of England’s U. of Reading • Studied at the Normal School (now Imperial College London) with T.H. Huxley. • Schoolteacher, minor journalist until publication of The Time Machine (1895). • By 1910, known worldwide for his “scientific romances” and sociological forecasting. • By the 1920s, syndicated journalist moving in the highest social circles in England and USA. • Met Lenin, Stalin, and several US Presidents. • Outline of History (1920) a massive best-seller. • World State his philosophical goal; Sankey Declaration/UN -

The New Machiavelli

THE NEW MACHIAVELLI by H. G. Wells CONTENTS BOOK THE FIRST: THE MAKING OF A MAN CHAPTER THE FIRST ~~ CONCERNING A BOOK THAT WAS NEVER WRITTEN CHAPTER THE SECOND ~~ BROMSTEAD AND MY FATHER CHAPTER THE THIRD ~~ SCHOLASTIC CHAPTER THE FOURTH ~~ ADOLESCENCE BOOK THE SECOND: MARGARET CHAPTER THE FIRST ~~ MARGARET IN STAFFORDSHIRE CHAPTER THE SECOND ~~ MARGARET IN LONDON CHAPTER THE THIRD ~~ MARGARET IN VENICE CHAPTER THE FOURTH ~~ THE HOUSE IN WESTMINSTER BOOK THE THIRD: THE HEART OF POLITICS CHAPTER THE FIRST ~~ THE RIDDLE FOR THE STATESMAN CHAPTER THE SECOND ~~ SEEKING ASSOCIATES CHAPTER THE THIRD ~~ SECESSION CHAPTER THE FOURTH ~~ THE BESETTING OF SEX BOOK THE FOURTH: ISABEL CHAPTER THE FIRST ~~ LOVE AND SUCCESS CHAPTER THE SECOND ~~ THE IMPOSSIBLE POSITION CHAPTER THE THIRD ~~ THE BREAKING POINT Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com BOOK THE FIRST: THE MAKING OF A MAN Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com CHAPTER THE FIRST ~~ CONCERNING A BOOK THAT WAS NEVER WRITTEN 1 Since I came to this place I have been very restless, wasting my energies in the futile beginning of ill- conceived books. One does not settle down very readily at two and forty to a new way of living, and I have found myself with the teeming interests of the life I have abandoned still buzzing like a swarm of homeless bees in my head. My mind has been full of confused protests and justifications. In any case I should have found difficulties enough in expressing the complex thing I have to tell, but it has added greatly to my trouble that I have a great analogue, that a certain Niccolo Machiavelli chanced to fall out of politics at very much the age I have reached, and wrote a book to engage the restlessness of his mind, very much as I have wanted to do. -

AIF Battalion Commanders in the Great War the 14Th Australian Infantry Battalion – a Case Study by William Westerman

THE JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1980 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2017 NUMBER 108 www.westernfrontassociation.com 2017 Spring Conference and AGM MAY University of Northumbria, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 1XE Programme for the day 9.30am Doors open. Teas/coffees 10.15am Welcome by the Chairman 10.20am British casualty evacuation from the Somme, 6 July 1916: success or failure? by Jeremy Higgins 11.20am Winning With Laughter: Cartoonists at War by Luci Gosling Newcastle upon Tyne 12.20pm buffet lunch 1.20pm Politics and Command: Conflict and Crisis 1917 by John Derry 2.20pm Teas/coffees 2.45pm AGM 4.30pm Finish of proceedings FREE EVENT / BUFFET LUNCH AT COST A loose leaf insert will be sent out with the next Bulletin (107) giving full details. Contact the WFA office to confirm your attendance and reserve your place. JUNE 6th WFA JULY WFA York President’s Conference Conference Saturday 8th July 2017 Doors 09.00 Saturday 3rd June 2017 Start 09.45 until 16.15 Doors 09.00 Manor Academy, Millfield Lane, 3 Start 09.45 until 16.30 8 Nether Poppleton, York YO26 6AP Tally Ho! Sports and Social Club, Birmingham Birmingham B5 7RN York l An Army of Brigadiers: British Commanders l The Wider War in 1917: Prof Sir Hew Strachan at the Battle of Arras 1917: Trevor Harvey l British Propaganda and The Third Battle l Arras 1917 - The lost opportunity: of Ypres: Prof. Stephen Badsey Jim Smithson l If we do this, we do it properly: l Messines 1917 - The Zenith of Siege The Canadian Corps at Passchendaele 1917: Warfare: Lt. -

Civilian Specialists at War Britain’S Transport Experts and the First World War

Civilian Specialists at War Britain’s Transport Experts and the First World War CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS Civilian Specialists at War Britain’s Transport Experts and the First World War New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather Shore (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Jane Winters (School of Advanced Study, University of London) Founding co-editors: Simon Newman (University of Glasgow) and Penny Summerfield (University of Manchester) New Historical Perspectives Editorial Board Charlotte Alston, Northumbria University David Andress, University of Portsmouth Philip Carter, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Ian Forrest, University of Oxford Leigh Gardner, London School of Economics Tim Harper, University of Cambridge Guy Rowlands, University of St Andrews Alec Ryrie, Durham University Richard Toye, University of Exeter Natalie Zacek, University of Manchester Civilian Specialists at War Britain’s Transport Experts and the First World War Christopher Phillips LONDON ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS Published in 2020 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © Christopher Phillips 2020 The author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. H. G. Wells, Interview with the Weekly Sun Literary Supplement, 1 December 1895; reprinted in ‘A Chat with the Author of The Time Machine, Mr H. G. Wells’, edited with comment by David C. Smith, The Wellsian, n.s. 20 (1997), 3–9 (p. 8). 2. Wells himself labelled his early scientific fantasies as ‘scientific romances’ when he published a collection with Victor Gollancz entitled The Scientific Romances of H. G. Wells in 1933, thus ensuring the adoption of the term in subsequent critical discussions of his work. The term appears to have origi- nated with the publication of Charles Howard Hinton’s Scientific Romances (1886), a collection of speculative scientific essays and short stories. 3. It should be noted, however, that Wells’s controversial second scientific romance, The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), did not appear in a serialised form. However, The Invisible Man was published in Pearson’s Weekly in June and July 1897, When the Sleeper Wakes was published in The Graphic between January and May 1899, The First Men in the Moon was published in the Strand Magazine between December 1900 and August 1901 and A Modern Utopia was serialised in the Fortnightly Review between October 1904 and April 1905. 4. A number of Wells’s most significant scientific essays have been available for some time in an anthology, H. G. Wells: Early Writings in Science and Science Fiction, ed. by Robert M. Philmus and David Y. Hughes (London: University of California Press, 1975). 5. ‘A Chat with the Author of The Time Machine’, p. -

Literacy Skills Teacher's Guide for 1 of 3 the Time Machine (Unabridged) by H.G

Literacy Skills Teacher's Guide for 1 of 3 The Time Machine (Unabridged) by H.G. Wells Book Information The novel begins with the Time Traveller convening with a group of men mostly referred to by their H.G. Wells, The Time Machine (Unabridged) occupations. He speaks of scientific and geometric Quiz Number: 12799 TOR Books,1992 theories, then subtly hints at the purpose of their ISBN 0-8125-0504-2; LCCN gathering: to introduce them to the reality of time 120 Pages travel. The Time Traveller then produces a small, Book Level: 7.4 glittering, metallic item: a model of his Time Interest Level: UG Machine. To prove its authenticity, he has the Psychologist pull a lever and the little machine An incredible invention enables the Time Traveller to disappears. Most of the men ponder its reach year 802701. whereabouts and speculate over the possibility of some trick or illusion. He then shows the men his Topics: Adventure, Discovery/Exploration; Classics, Time Machine and agrees to show them more at a Classics (All); Popular Groupings, College later date. Bound; Power Lessons AR, Grade 7; Science Fiction, Future; Science Fiction, Once again, the men have gathered at the Time Time Travel Traveller's house. The Time Traveller arrives a bit late for supper, looking quite disheveled and Main Characters hungering for meat. One of the men asks him if he Eloi the carefree, fun-loving, and childlike species has been time travelling, and he replies that he has. of future human beings who live above ground After dining, he proceeds to tell the men of his Morlocks the frightening and mechanically-minded adventure into the future. -

Futures Studies and Alternative Military Futures

JOERNAAL/JOURNAL VREŸ FUTURES STUDIES AND ALTERNATIVE MILITARY FUTURES F Vreÿ* 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of Futures Studies is threefold: To discover or invent, examine and evaluate, and propose possible, probable and preferable futures.1 This triad of purposes is primarily addressed via futures research of which the essence is to generate alternative futures as choices for decision-makers.2 It is within the idea of alternatives, it can be argued, that the purpose of Futures Studies find meaning. This in turn raises the difficulty of clarifying the future and therefore the practice of rather presenting it as alternatives than a rigid prediction. History however, points out that this was not always the case. Viewing the future as unfolding alternatives only came about after the First and Second World Wars as the connection between war and how the future is to be perceived became more lucid.3 If the argument is upheld that the importance of Futures Studies increases as the world becomes a more complicated realm, then current military-strategic complexities facing defence decision-makers should not be excluded or marginalised. Furthermore, if the rate of global change and resultant complexities are to increase, demands for clarity about military futures ought to increase as well. Future change and military futures therefore have an enduring interface in spite of efforts to downplay this relationship. Although Spies4 avers that military futures are not more complex than non-military ones, history clearly illustrates the dangerous potential of the deep destruction of war. The future of this destructive potential is increasingly debated and questioned in contemporary times and a rationale for investigating the link between Futures Studies and military futures. -

WORLD WAR ONE WAR WORLD Research Guide World War One

WORLD WAR ONE WAR WORLD Research Guide World War One 1 King’s College London Archives & Special Collections Archives College London King’s Sections of this guide 1. Prelude to war 5 2. High Command & strategy 7 3. Propaganda 9 4. Military & naval campaigns 11 5. Technology of war 18 6. Empire & dominions 22 7. Health & welfare 24 8. Aftermath 27 9. Memorials 30 10. Writing the war 32 Library Services 2014 DESIGN & PRODUCTION Susen Vural Design www.susenvural.com 2 March 2014 Introduction Archives Online resources The Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives www.kcl.ac.uk/archivespec/collections/resources (LCHMA) holds nearly 200 collections These include: relating to World War One. They include The Serving Soldier portal, giving access to orders, reports, diaries, letters, telegrams, log thousands of digital copies of unique diaries, books, memoranda, photographs, memoirs, correspondence, scrapbooks, photographs and maps, posters, press cuttings and memorabilia. other LHCMA archive items, from the late For more information, please see the online 19th century to World War Two, scanned as LHCMA World War One A-Z listing under part of a JISC-funded project. research guides at www.kcl.ac.uk/archivespec King’s College London Archives are Lest We Forget, a website created by King’s among the most extensive and varied higher College London Archives and the University education collections in the UK. They include of the Third Age (U3A), to commemorate the institutional records of King’s since 1828, the 20th century war dead of King’s College records relating to King’s College Hospital and London and the institutions with which it the medical schools of Guy’s and St Thomas’ has merged, including the Medical Schools of Hospitals, and records relating to other Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals.