This Is the Fire Brigades Union's (FBU)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Challenge to the Trade Unions

The Conservative Government’s Proposed Strike Ballot Thresholds: The Challenge to the Trade Unions Salford Business School Research Working Paper August 2015 Professor Ralph Darlington Salford Business School, University of Salford, and Dr John Dobson Riga International College of Economics and Business Administration Corresponding author: Professor Ralph Darlington, Salford Business School, University of Salford, Salford M5 4WT; [email protected]; 0161-295-5456 Ralph Darlington is Professor of Employment Relations at the University of Salford. His research is concerned with the dynamics of trade union organisation, activity and consciousness in Britain and internationally within both contemporary and historical settings. He is author of The Dynamics of Workplace Unionism (Mansell, 1994) and Radical Unionism (Haymarket, 2013); co-author of Glorious Summer: Class Struggle in Britain, 1972, (Bookmarks, 2001); and editor of What’s the Point of Industrial Relations? In Defence of Critical Social Science (BUIRA, 2009). He is an executive member of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association and secretary of the Manchester Industrial Relations Society. John Dobson has published widely on the operation of labour markets in Central and Eastern Europe and is currently Associated Professor at Riga International College of Economics and Business Administration, Latvia. He was previously a senior lecturer in Industrial Relations at the University of Salford, where he was Head of the School of Management (2002-6) and President -

Dinosaurs and Donkeys: British Tabloid Newspapers

DINOSAURS AND DONKEYS: BRITISH TABLOID NEWSPAPERS AND TRADE UNIONS, 2002-2010 By RYAN JAMES THOMAS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY The Edward R. Murrow College of Communication MAY 2012 © Copyright by RYAN JAMES THOMAS, 2012 All rights reserved © Copyright by RYAN JAMES THOMAS, 2012 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of RYAN JAMES THOMAS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. __________________________________________ Elizabeth Blanks Hindman, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________________ Douglas Blanks Hindman, Ph.D. __________________________________________ Michael Salvador, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation, not to mention my doctoral degree, would not be possible with the support and guidance of my chair, Dr. Elizabeth Blanks Hindman. Her thoughtful and thorough feedback has been invaluable. Furthermore, as both my MA and doctoral advisor, she has been a model of what a mentor and educator should be and I am indebted to her for my development as a scholar. I am also grateful for the support of my committee, Dr. Douglas Blanks Hindman and Dr. Michael Salvador, who have provided challenging and insightful feedback both for this dissertation and throughout my doctoral program. I have also had the privilege of working with several outstanding faculty members (past and present) at The Edward R. Murrow College of Communication, and would like to acknowledge Dr. Jeff Peterson, Dr. Mary Meares, Professor Roberta Kelly, Dr. Susan Dente Ross, Dr. Paul Mark Wadleigh, Dr. Prabu David, and Dr. -

Register of Interests of Members’ Secretaries and Research Assistants

REGISTER OF INTERESTS OF MEMBERS’ SECRETARIES AND RESEARCH ASSISTANTS (As at 11 July 2018) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register In accordance with Resolutions made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985 and 28 June 1993, holders of photo-identity passes as Members’ secretaries or research assistants are in essence required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £380 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass. Any gift (eg jewellery) or benefit (eg hospitality, services) that you receive, if the gift or benefit in any way relates to or arises from your work in Parliament and its value exceeds £380 in the course of a calendar year.’ In Section 1 of the Register entries are listed alphabetically according to the staff member’s surname. Section 2 contains exactly the same information but entries are instead listed according to the sponsoring Member’s name. Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. An Exploration of Culture and Change in the Scottish Fire Service: The Effect of Masculine Identifications Brian M. Allaway PhD by Research The University of Edinburgh 2010 1 Abstract This study examines the organisational culture of the Scottish Fire Service, and the political pressures for change emanating from the modernisation agenda of both the United Kingdom and Scottish Governments. Having completed a preliminary analysis of the Fire Service‟s culture, by examining the cultural history of the Scottish Fire Service and the process through which individuals are socialised into the Service, the study analyses the contemporary culture of the Service through research in three Scottish Fire Brigades. This research concludes that there is a clearly defined Fire Service culture, which is predicated on the operational task of fighting fire, based on strong teams and infused with masculinity at all levels. -

Influences on Trade Union Organising Effectiveness in Great Britain

Abstract This paper brings together data from the 1998 Workplace Employee Relations Survey, National Survey of Unions and TUC focus on recognition survey to investigate influences on union organising effectiveness. Organising effectiveness is defined as the ability of trade unions to recruit and retain members. Results suggest that there are big differences in organising effectiveness between unions, and that national union recruitment policies are an important influence on a union’s ability to get new recognition agreements. However local factors are a more important influence on organising effectiveness in workplaces where unions have a membership presence. There are also important differences in organising effectiveness among blue and white-collar employees. These differences suggest that unions will face a strategic dilemma about the best way to appeal to the growing number of white-collar employees. JEL classification: J51 Key words: Trade union objectives and structures, organising effectiveness This paper was produced under the ‘Future of Trade Unions in Modern Britain’ Programme supported by the Leverhulme Trust. The Centre for Economic Performance acknowledges with thanks, the generosity of the Trust. For more information concerning this Programme please email [email protected] Influences on Trade Union Organising Effectiveness in Great Britain Andy Charlwood August 2001 Published by Centre for Economic Performance London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE Ó Andy Charlwood, submitted June 2001 ISBN 0 7530 1492 0 Individual copy price: £5 Influences on Trade Union Organising Effectiveness in Great Britain Andy Charlwood Introduction 1 1. Organising Effectiveness: Concepts and Measures 2 2. Influences on Union Organising Effectiveness 5 3. -

Trade Unions and Climate Politics: Prisoners of Neoliberalism Or Swords of Climate Justice?

Trade unions and climate politics: prisoners of neoliberalism or swords of climate justice? 6 March 2015 Paper presented to the Political Studies Association Conference 2015, Sheffield, 30 March 2015 Dr Paul Hampton Head of Research and Policy Fire Brigades Union [email protected] 07740403240 02084811511 Dr Paul Hampton is Research and Policy Officer at the Fire Brigades Union. He is the author of numerous publications, including Lessons of the 2007 Floods ‐ the FBU’s contribution to the Pitt review (2008), Climate Change: Key issues for the fire and rescue service (2010) and Inundated: Lessons of recent flooding for the fire and rescue service (2015). He holds a PhD in climate change and employment relations, focusing on the role of trade unions in tackling global warming. His book, Workers and Unions for Climate Solidarity is due to be published by Routledge this year. This is a work in progress. Please do not quote or distribute. 1 Introduction The early decades of the twenty‐first century have witnessed the failure of climate change politics. The failure is not principally with the physical science evidence for climate change, which as a scientific hypothesis is increasingly robust, although still evolving and variously contested. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports articulate the widely‐ held but conservative consensus around the physical science of climate change: the climate system is now warming significantly and is likely to continue, human activities are the major cause of it and potentially large impacts are likely (IPCC 2013). The fifth IPCC report predicts significant increases in surface warming and sea level by the end of this century. -

Fbu Supports Homerton Eleven 2

ESTABLISHED 1918 JOURNAL OF THE FIRE BRIGADES UNION F ir e F ig h t e r VOL 28 NO. 1 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2000 FBU SUPPORTS HOMERTON ELEVEN 2 CONFERENCE TRESSELL FESTIVAL 2000 HE Robert Tressell Centre has been set up, with the support of Trade Unions both locally and nationally, to preserve and promote the memory of Robert Tressell author HE Annual Conference this Tof the classic working class novel, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist. One of the year will have many significant major undertakings of the group is the Robert Tressell Festival, the second of which will be Telements contained within it, held over the weekend of the 27th/28th May 2000. The inaugural event last year was a great apart from the fact that it will be success with trade unionists and other enthusiasts travelling from around the country to the first of the new millennium. Hastings. Apart from the Festival the group are trying to introduce a whole new generation To mark this occasion it is of readers to this wonderful work via schools and libraries. For further information please proposed to produce for the week contact Dee Daly at the Robert Tressell Centre, 84 Bohemia Road, St Leonards on Sea, East of Conference, in print and on the Sussex, TN37 6RN or visit the website at: www.1066.net/tressell Website, a Conference 2000 special edition of Firefighter. To do this the Executive Council need your help. THOMPSONS & THE FBU The Journal will hopefully contain articles, letters, and photos of how UNION LEGAL SERVICES this Union has grown and evolved over the 20th Century and also NION legal services are substantially cheaper than any other legal expenses look forward to how it will progress insurance, according to a TUC survey, Focus on Union Legal Services. -

No.9 Trade Unions and Other Employees' Associations

This Information Note lists trade unions and other employees' associations representing the interests of workers in Northern Ireland. The Agency updates the list as frequently as possible and is therefore grateful to receive notification of any additions or amendments required. INFORMATION NOTE NO 9 MARCH 2015 TRADE UNIONS AND OTHER EMPLOYEES’ ASSOCIATIONS IRISH CONGRESS OF TRADE UNIONS (NORTHERN IRELAND COMMITTEE) Mr. Peter Bunting, Assistant General Secretary 4-6 Donegall Street Place, Belfast, BT1 2FN Phone: 02890 247940 Fax: 02890 246898 Website: www.ictuni.org UNITE Regional secretary Mr. Jimmy Kelly: 26 – 34 Antrim Road, Belfast, BT15 2AA Phone: 02890 232381 Fax: 02890 748052 Regional Women's Officer Ms Taryn Trainor: 26 – 34 Antrim Road, Belfast, BT15 2AA Phone: 02890 232381 Fax: 02890 748052 Branch Secretaries Mr Maurice Cunningham: (BELFAST) Mr David McMurray: (BELFAST) 26 – 34 Antrim Road, Belfast, BT15 2AA Phone: 028 9023 2381 Fax: 02890 748052 Mr Davey Thompson: (BALLYMENA) The Pentagon, 2 Ballymoney Road, Ballymena, BT43 5BY Phone: 028 2565 6216 Fax: 028 2564 6334 1 Organisers Mr Dessie Henderson 26 – 34 Antrim Road, Belfast, BT15 2AA Phone: 028 9023 2381 Fax: 02890 748052 Regional Officers Mr Jackie Pollock 26 – 34 Antrim Road, Belfast, BT15 2AA Phone: 028 9023 2381 Fax: 02890 748052 Mr Philip Oakes 4 Foyle Road, Londonderry, BT48 6SR Phone: 028 71220214 Fax: 028 7137 3171 Mr Kevin McAdam 26 – 34 Antrim Road, Belfast, BT15 2AA Phone: 028 9023 2381 Fax: 02890 748052 Mr Gareth Scott: (Londonderry and District) 4 Foyle Road, -

Trade Union Facility Time

TRADE UNION FACILITY TIME Facility time arrangements at the Isle of Wight Council The Isle of Wight council whilst having statutory obligations to comply with employment legislation to make provision for trade union facility time believes in the benefits that can be realised by positive employee relations. All facility time arrangements are set out in an agreement in which all parties can make a positive contribution to the efficient and effective management of council services by setting out the consultation processes, conditions of recognition and facilities which will be made available to Union representatives and specifying how reasonable time off for union duties and activities, training and for health and safety, can work to the mutual advantage of both parties. The agreement takes account of current practices within the council; employment protection legislation; the ACAS Code of Practice 3 for time off for trade union duties and activities, the health and safety commission code of practice on safety representatives and appropriate national agreements. The council affords reasonable time off with pay to trade union representatives, subject to the needs of the service, to carry out duties concerned with employee relations and the members they represent. The purpose for this time off must be either to carry out official union duties or to undergo relevant training as approved by the TUC or Trade Union. The amount of time-off a steward may take to undertake official union duties in their particular constituency should not normally exceed one day per month, with an additional two hours per month plus travelling time being allowed to attend Union meetings to discuss employee relations matters concerning the Council. -

Investigation Into the King's Cross Underground Fire

Investigation into the King's Cross Underground Fire Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Transport by Command of Her Majesty November 1988 1 THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT LONDON HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE £19.50 net Investigation into the King's Cross Underground Fire Inspector: Department of Transport Mr Desmond Fennell OBE QC 2 Marsham Street London SWlP 3EB 21 October 1988 The Rt Hon. Paul Channon MP Secretary of State for Transport Department of Transport 2 Marsham Street London SWlP 3EB Dear Secretary of State, King's Cross Underground Fire Investigation I was appoipted by you on 23 November 2987 to hold a formal Investigation into the circumstances of the King's Cross Underground fire. I have completed the Investigation and enclose my Report. Yours sincerely, Desmond Fennell T022b8O 000Lb75 AT7 W Contents Page CHAPTER 1 Executive Summary ................................................................. 15 CHAPTER 2 Introduction and Scope of the Investigation .................. 21 CHAPTER 3 London Regional Transport and London Underground Limited ................................................................25 CHAPTER 4 The Ethos of London Underground ................................. 29 CHAPTER 5 London Underground Organisation and Management 33 CHAPTER 6 King's Cross Station ............................................................ 37 CHAPTER 7 Escalators on the Underground ..................................... 41 CHAPTER 8 Staff on duty at King's Cross on 18 November 1987 47 CHAPTER 9 Timetable and Outline -

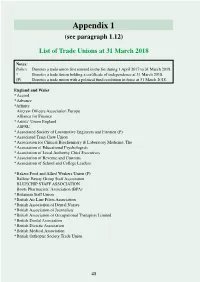

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Executive Council's Report 2020

EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REPORT 2020 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REPORT 2020 COUNCIL’S REPORT EXECUTIVE Bradley House 68 Coombe Road Kingston upon Thames Surrey KT2 7AE twitter: @fbunational website: www.fbu.org.uk CREDIT: FRASER SMITH 20304 FBU Exec Council Rep 2020 COVER.indd 1 27/05/2020 15:36 Established 1 October 1918 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REPORT 2020 President: Ian Murray Vice-president: Andy Noble General secretary: Matt Wrack Assistant general secretary: Andy Dark Treasurer: Jim Quinn National offi cers: Dave Green Tam McFarlane Mark Rowe Sean Starbuck Bradley House Telephone: 020 8541 1765 68 Coombe Road website: www.fbu.org.uk Kingston upon Thames email: offi [email protected] Surrey twitter: @fbunational KT2 7AE FBU EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REPORT 2020 1 20304 FBU Intro pages Exec Council Rep 2020.indd 1 27/05/2020 15:56 Established 1 October 1918 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REPORT 2020 President: Ian Murray Vice-president: Andy Noble General secretary: Matt Wrack Assistant general secretary: Andy Dark Treasurer: Jim Quinn National offi cers: Dave Green Tam McFarlane Mark Rowe Sean Starbuck Bradley House Telephone: 020 8541 1765 68 Coombe Road website: www.fbu.org.uk Kingston upon Thames email: offi [email protected] Surrey twitter: @fbunational KT2 7AE FBU EXECUTIVE COUNCIL’S REPORT 2020 1 20304 FBU Intro pages Exec Council Rep 2020.indd 1 27/05/2020 15:56 CONTENTS PRESIDENT’S INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................7