LTBMU Final Pre-Scoping Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Center Comments to the California Department of Fish and Game

July 24, 2006 Ryan Broderick, Director California Department of Fish and Game 1416 Ninth Street, 12th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Improving efficiency of California’s fish hatchery system Dear Director Broderick: On behalf of the Pacific Rivers Council and Center for Biological Diversity, we are writing to express our concerns about the state’s fish hatchery and stocking system and to recommend needed changes that will ensure that the system does not negatively impact California’s native biological diversity. This letter is an update to our letter of August 31, 2005. With this letter, we are enclosing many of the scientific studies we relied on in developing this letter. Fish hatcheries and the stocking of fish into lakes and streams cause numerous measurable, significant environmental effects on California ecosystems. Based on these impacts, numerous policy changes are needed to ensure that the Department of Fish and Game’s (“DFG”) operation of the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not adversely affect California’s environment. Further, as currently operated, the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not comply with the California Environmental Quality Act, Administrative Procedures Act, California Endangered Species Act, and federal Endangered Species Act. The impacts to California’s environment, and needed policy changes to bring the state’s hatchery and stocking program into compliance with applicable state and federal laws, are described below. I. FISH STOCKING NEGATIVELY IMPACTS CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE SALMONIDS, INCLUDING THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES Introduced salmonids negatively impact native salmonids in a variety of ways. Moyle, et. al. (1996) notes that “Introduction of non-native fish species has also been the single biggest factor associated with fish declines in the Sierra Nevada.” Moyle also notes that introduced species are contributing to the decline of 18 species of native Sierra Nevada fish species, and are a major factor in the decline of eight of those species. -

DONNER LAKE - AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES MANDATORY SELF-INSPECTION LAUNCH CERTIFICATE PERMIT Town of Truckee Ordinance 2020-03 Chapter 14.01

DONNER LAKE - AQUATIC INVASIVE SPECIES MANDATORY SELF-INSPECTION LAUNCH CERTIFICATE PERMIT Town of Truckee Ordinance 2020-03 Chapter 14.01 Must Complete, sign, and date this Launch Certification Permit and keep in the vessel. If this is the first inspection of the year, the owner or operator of the vessel shall submit a self-inspection form to the Town of Truckee and obtain an inspection sticker for the vessel. *All motorized watercraft STILL require an inspection before launching into Donner Lake. Non-motorized watercraft are also capable of transporting aquatic invasive species. It is highly recommended to complete a self-inspection on all watercraft. Vessel Registration Number: Zip Code: Date: Boat Type (circle one): Ski/Wake Sail PWC/Jet Ski Fishing Pleasure Boat Wooden Non-Moto Other: Last Waterbody visited with this watercraft: 1. Is your vessel, trailer and all equipment clean of all mud, dirt, plants, fish or animals and drained of all water including all bilge areas, fresh-water cooling systems, lower outboard units, ballast tanks, live-wells, buckets, etc. and completely dry? YES, my vessel is Clean, Drain and Dry No, my vessel is NOT Clean, Drain and Dry. Vessel must be cleaned, drained and completely dry before it will be permitted to launch. Do not clean or drain your vessel by the lake or at the launch ramp. See below for details on how to properly clean your vessel and equipment prior to launching. 2. Has your vessel been in any of the infested waters listed on the back page of this form within the last 30 days? YES, my vessel has been in an infested body of water: Go to question 3 No, my vessel has NOT been in an infested body of water: You are ready to launch. -

Renew the Government T a ATES OF

NT O ME F T EN R E A R P G E Y D • • U N A I C T I E R D E S M Renew the Government T A ATES OF U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Summary of Projects and Lessons Learned U.S. Department of Energy • Sandia National Laboratories • Bureau of Land Management National Park Service • USDA Forest Service Partners in Expanding the use of Renewable Energy SAND98-1943 Click here to see a listing of government Projects by State (Excel database) RENEW THE GOVERNMENT SUMMARY OF PROJECTS AND LESSONS LEARNED ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A special thanks goes to Jim Rannels, DOE Office of Photovoltaic and Wind Technology, and Anne Sprunt Crawley, DOE Federal Energy Management Program, without whose support the Renew the Government effort would not have been possible. We also wish to express our appreciation to Doug DeNio, National Park Service (retired), and Fred Bloom, formerly Tonto National Forest, for their commitment and enthusiasm in setting the groundwork that allowed this effort to go forward. Gabriella Cisneros and Vern Risser of the Southwest Technology Development Institute helped develop the project information database. Anne Van Arsdall and Connie Brooks, Sandia National Laboratories, provided significant editorial assistance and Subia was responsible for the publication design. Our biggest thanks, however, goes to the many Park, BLM, and Forest participants who chose to get involved in using photovoltaics and to the U.S. photovoltaics industry who provided the quality systems that made this endeavor successful. Hal Post and Mike Thomas Trent Duncan Photovoltaic Systems Assistance Center Utah State Office Sandia National Laboratories Bureau of Land Management Pat Fleming Andrew Dziobek Denver Service Center Tonto National Forest National Park Service USDA Forest Service ABSTRACT For the past several years, the Photovoltaic Systems Assistance Center at Sandia National Laboratories has maintained collaborative partnerships with the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and USDA Forest Service. -

LWCF Projects 1964 to 2019

FiscalYear CountyName AgencyName ProjectNumber ProjectName ProjectScope GrantAmount ProjectAddress ProjectCity ProjectZipCod Latitude Longitude e 2018/19 Kern City of Bakersfield 06-01827 Kaiser Permanente Construct 4 new football fields, a restroom and concession $3,000,000 9001 Ashe Road Bakersfield 93313 NULL NULL Sports Village stand, exercise outdoor gym area, 3 parking lots, Project installation of sports field lighting, and landscaping at the Kaiser Permanente Sports Village in the City of Bakersfield. 2018/19 Humboldt City of Eureka 06-01826 Sequoia Park Construct new trails, playground facilities, off-street ADA $1,525,000 3414 W Street Eureka 95503 NULL NULL Redwood Canopy compliant parking and new restrooms and renovate trails Walk and Trail in Sequoia Park in the City of Eureka. Project 2018/19 Riverside City of Indio 06-0130 South Jackson Park Construct a new approximately 0.5 mile trail with exercise $652,500 83100 Date Indio 92201 NULL NULL Accessibility stations and plant approximately 50 new trees, renovate Avenue Improvements existing playgrounds and provide ADA improvements at South Jackson Park in the City of Indio. 2018/19 Los Angeles City of Long Beach 06-01828 Davenport Park Construct a new multi-use sports field, shaded outdoor $2,016,000 2910 East 55th Long Beach 90805 NULL NULL Phase II seating area, and install exercise equipment with signage Way in Davenport Park in the City of Long Beach. 2018/19 Madera County of Madera 06-01829 Courthouse Park Construct a new playground, exercise stations, and picnic $203,747 210 W. Yosemite Madera 93637 NULL NULL Project area at Courthouse Park in the City of Madera. -

Assessing Willow Flycatcher Population Size and Distribution to Inform Meadow Restoration Priorities in the Sierra Nevada and Southern Cascades

Produced by The Institute for Bird Populations’ Sierra Nevada Bird Observatory ASSESSING WILLOW FLYCATCHER POPULATION SIZE AND DISTRIBUTION TO INFORM MEADOW RESTORATION PRIORITIES IN THE SIERRA NEVADA AND SOUTHERN CASCADES September 25, 2014 Helen Loffland and Rodney Siegel Chris Stermer The Institute for Bird Populations Staff Environmental Scientist P.O. Box 1346 California Department of Fish and Wildlife Point Reyes Station, CA 94956 1812 Ninth Street www.birdpop.org Sacramento, CA 95811 Ryan Burnett and Brent Campos Tina Mark Point Blue Conservation Science Wildlife, Aquatics, Rare Plant Program Manager P.O. Box 634 Tahoe National Forest Chester, CA 96020 631 Coyote Street www.pointblue.org Nevada City, CA 95959 Above: Willow Flycatcher (inset) and breeding habitat at Red Lake Peak, Alpine County. The Institute for Bird Populations Willow Flycatcher Population Status in the Sierra Nevada Recommended citation: Loffland, H. L., R. B. Siegel, R. D. Burnett, B. R. Campos, T. Mark, C. Stermer 2014. Assessing Willow Flycatcher population size and distribution to inform meadow restoration in the Sierra Nevada and Southern Cascades. The Institute for Bird Populations, Point Reyes Station, California. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank countless agencies and individuals for conducting recent and historic Willow Flycatcher surveys and sharing data for this synthesis. This project was made possible by a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and was conducted by The Institute for Bird Populations’ Sierra Nevada Bird Observatory. This is Contribution No. 483 of The Institute for Bird Populations. i The Institute for Bird Populations Willow Flycatcher Population Status in the Sierra Nevada Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... -

Tahoe's Seven Summits

Birds return to Lake Tahoe, page 4 Summer 2014 Drought offers TAHOE’S SEVEN SUMMITS good news, bad By Jeff Cowen news for Lake Tahoe In Depth By Jim Sloan The Lake may be this Region’s Tahoe In Depth most famous geographic feature, but it is Tahoe’s peaks that define our From the shoreline, a long-term landscapes and, at times, the course or severe drought seems to put of our lives. Daily, we glimpse them Lake Tahoe in dire straits. The water towering over our tedium, indelible recedes, streams dry up and the reminders of nature’s greatness and our shoreline beaches expand to expose own impermanence. Succumbing to a bathtub ring along the 72-mile their power, we climb them. shoreline. Some climbers are peak collectors, But from the water, things don’t “bagging” the major summits one by always look so bad. During a one. Others climb on a lark, impulsively drought, many of the pollutants joining friends and unprepared for the that affect Lake Tahoe’s clarity can’t Photo © Steve Dunleavy experience ahead. Regardless of our Pyramid Peak rises above the fog-choked Tahoe Basin. find their way to the Lake. Droughts paths, once we reach their summits, we slow down the rate of urban runoff, feel at once tiny and expansive, earth and rodents. Trees become shorter and neighborhoods. reducing erosion and the flow of fine and time stretching in all directions wider, until they disappear entirely. Our Climbers of even our most benign sediment and other water-clouding below us, the experience undeniably bodies change too. -

Lake Tahoe West Update

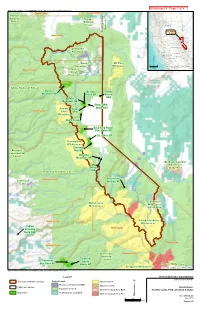

LAKE TAHOE WEST LANDSCAPE RESTORATION STRATEGY AUGUST 2019 Lake Tahoe’s west shore is one of America’s treasured landscapes, with towering forests, clear blue lakes, and snow- covered alpine peaks. Yet wildfire, drought, insect outbreaks, and flooding—all amplified by climate change—threaten this 60,000-acre landscape. The Lake Tahoe West Restoration Partnership (Lake Tahoe West) is changing this. By pooling resources and collaborating across jurisdictions, Lake Tahoe West is taking an all lands approach to restoring the resilience of the west shore to disturbance. This includes the forests, communities, recreational opportunities, and watersheds that stretch from the shoreline all the way to the ridgetops, from Emerald Bay north to Tahoe City. As described in the Lake Tahoe West Landscape Resilience Assessment (2017), west shore forests are Lake Tahoe West will: overly dense, uniform, and susceptible to high severity fire, especially in lower elevations and canyons. Trees 1. Plan restoration actions based on landscape- specific scientific analysis and modeling. and plants are dense near the ground, creating ladder fuels that could carry flames into the tree tops. These 2. Coordinate restoration at the landscape scale, unhealthy conditions also leave large areas of forest across land ownerships. at high risk to insects and disease. Eighty percent of 3. Restore the resilience of forests, watersheds, streams on the west shore have barriers that may block and communities in the face of climate change. fish from passing upstream. 4. Explore new methods for treatments in areas that are challenging to manage, such as steep With so many acres to treat, land managers are relying slopes and streams. -

Attachment 4 Page 1 of 4

Path: Z:\Projects\TahoeSierraIRWMP\Events\F 2-2 Federal Lands and State Parks.mxd Plumas County Lassen County Del Norte Plumas a Siskiyou Modoc i National a Toiyabe n d Forest r National a o Shasta a i f v a Trinity n Forest i Redding d !( Lassen r e Humboldt l a o f v i N a e l N a C Tehama T-S IRWM C Region Plumas Sierra County Mendocino Glenn Butte Sierra !( Reno Nevada !( Colusa Truckee !( Carson Placer Lake City South Lake Tahoe !( Yolo El Dorado Sonoma Napa !( Sacramento Stampede Alpine Solano Mono Reservoir San Tuolumne !( Francisco Stockton !( !( Oakland Alameda !( Modesto San Jose Mariposa !( Santa Madera ¢ Clara Merced Boca Mt. Rose Fresno 0 25 50 !( Fresno Reservoir Wilderness Sources: USaSn GS, Esri, TANA, Monterey Benito Miles AND Tulare Nevada County Prosser Creek Reservoir Tahoe National Forest Donner Burton Kings Memorial SP Creek SP Beach Antone SRA Meadows NP Tahoe SRA Granite Tahoe - Skylandia Placer County Chief SRA Wilderness Ward Creek Ed Z'berg Sugar Pine Point SP D.L. Bliss SP Desolation Wilderness Emerald Blodgett Bay SP Experimental Washoe Forest Meadows SP Burbank Canyons Lake Wilderness Valley Study Area SRA Eldorado National Forest El Dorado County Grover Hot Jenkinson Springs SP Lake Slinkard Mokelumne Wilderness Wilderness Study Area Amador County Carson-Iceberg Wilderness Indian Alpine County Grinding Rock SHP Mono County Calaveras County Stanislaus Tuolumne County National Calaveras Forest Calaveras South Big Trees SP Grove NP Hoover Wilderness Emigrant Wilderness Sources: USGS, Esri, TANA, AND Source: National Atlas of the united States, 2005 and California State Parks, 2011 Legend Kennedy/Jenks Consultants Tahoe-Sierra IRWMP Tahoe-Sierra IRWM Boundary Federal Lands Wilderness FS Bureau of Reclamation BOR Wilderness NPS California Counties Jurisdictions: National Forest FS Wilderness Study Area BLM Federal Lands, Parks (Federal & State) State Parks Public Domain Land BLM Wilderness Study Area FS ³ K/J 1270036.00 0 4 8 July 2013 Miles Figure 2-2 U.S. -

Draft Revised Land and Resource Management Plan

United States Department of Agriculture Draft Revised Forest Land and Resource Management Plan Service Pacific Southwest Volume III – Region DEIS and Draft Plan Appendices R5-MB-241C June 2012 Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit Cover photo: Eagle Falls Trail located on National Forest System lands on Lake Tahoe’s southwest shore. The trailhead and parking lot kiosk, across US Highway 89 from the Emerald Bay overlook, offer information about hiking into Desolation Wilderness, looking westward toward Eagle Lake, a popular short, but steep, hike (less than half an hour). Credit – all photos, graphs and maps: U.S. Forest Service staff, Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit may be duplicated for public use (not for profit) The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720- 6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

American Black Bears in California State Parks

Thanks to the following agencies merican for their assistance: A El Dorado County U.S. Forest Service, Black bears (Ursus americanus) BNamelack Bears of in Park Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit California Department of Fish and Game are an important component U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of California’s ecosystems and a CaliforniaState StatePark Parks Tahoe Council for Wild Bears Yosemite National Park valuable natural legacy for the Sequoia National Park people of California. The black California State Parks, Sierra District: bear is the only species of bear Mono Lake Tufa SNR remaining in California and Bodie SHP Grover Hot Springs SP Nevada. The common name Lake Valley SRA “black bear” is misleading; Washoe Meadows SP Emerald Bay SP California black bears may be DL Bliss SP Ed Z’berg Sugar Pine Point SP black, brown, cinnamon, even Ward Creek Unit blonde. Some bears have a Tahoe SRA Burton Creek SP white patch on the chest. Kings Beach SRA Donner Memorial SP Plumas Eureka SP Malakoff Diggins SHP Empire Mine SHP South Yuba River SP For more information contact: Photo: Park Office, Campground Entry Station or Janice Clark California State Parks Sierra District Headquarters State Parks and Campgrounds in the P. O. Box 266 7360 West Lake Blvd. (Highway 89) Sierra District are situated in areas Tahoma, CA 96142 that are also black bear habitat. (530) 525-7232 © 2008 California State Parks (Rev. 2010) Bear enCounters - Never approach a bear! In the campground: Do not run. Be aggressive; assert your dominance by standing tall Strict regulations are in place to and making noise to scare the bear away. -

Genus ID Species ID Full Name Collection Observation DB Record

Genus_ID Species_ID Full_Name Collection Observation DB_Record Pub_Record Pub_Record_Collection V_Country V_State/Province V_County Verbatim_Locality Other_Verbatim_Descriptor V_Habitat V_Elevation Date_Collected Month _Collected Year_Collected V_Determined_by V_Det_Year Male Female Adult_Unknown Larvae Pupae Exuvium V_Collector Inferred_Waterbody Inf_Latitude Inf_Longitude Inf_ Elev (ft) Max Error Neohermes Neohermes USU USA AZ Cochise South Fork Cave Creek EPA01-302 Targeted Riffle 22 V 2001 1 31.85199928 -109.1940002 Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise riffle #2 22 VI 2005 K. Bayley 2010 1 M. Bogan 31.99079 -109.15004 1.5miles Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise Ash Canyon riffle #3 19 III 2005 K. Bayley 2010 2 M. Bogan 31.38051 -110.24241 5600 2000feet Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise Ash Cyn Range: Galiuro riffle #2 19 III 2005 K. Bayley 2010 1 M. Bogan 31.38203 -110.24554 5300 3000feet Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise riffle #3 24 III 2005 K. Bayley 2010 1 M. Bogan 31.48989 -110.50812 5300 4000feet Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise Chiricahua WTU riffle #1 27 IV 2004 K. Bayley 2010 1 M. Bogan 31.86422 -109.35919 6000 3500feet Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise riffle #2 24 III 2005 K. Bayley 2010 4 M. Bogan 31.86422 -109.35919 6000 3500feet Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise Pinery Canyon, Chiricahua Rustler Park Rd. Riffle kick 6 XI 2006 K. Bayley 2010 4 M. Bogan 31.92470 -109.26464 7500 2500feet Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise Chiricahuas ETU riffle #1 22 IV 2004 K. Bayley 2010 1 M. Bogan 31.99079 -109.15004 1.5miles Neohermes Neohermes MTB USA AZ Cochise Chiricahua riffle #3 22 III 2005 K. -

Attachment a 303(D) List for Bodies of Water from RWQCB Basin Plans in Southern California

Attachment A 303(d) List for Bodies of Water from RWQCB Basin Plans in Southern California Regulatory_Issues_Trends.doc Attachment A-1 Lahontan RWQCB Basin Plan 303(d) List Regulatory_Issues_Trends.doc 2006 CWA SECTION 303(d) LIST OF WATER QUALITY LIMITED SEGMENTS REQUIRING TMDLS LAHONTAN REGIONAL WATER QUALITY CONTROL BOARD USEPA APPROVAL DATE: JUNE 28, 2007 CALWATER POTENTIAL ESTIMATED PROPOSED TMDL REGION TYPE NAME WATERSHED POLLUTANT/STRESSOR SOURCES SIZE AFFECTED COMPLETION 6 R Big Meadow Creek 63410011 Pathogens 1.4 Miles 2019 Range Grazing-Riparian and/or Upland Natural Sources Recreational and Tourism Activities (non-boating) 6 R Blackwood Creek 63420021 Iron 5.9 Miles 2015 Erosion/Siltation Natural Sources Nonpoint Source Nitrogen 5.9 Miles 2008 Nitrogen loading from creek to be addressed during development of Lake Tahoe TMDL, but a more specific TMDL may be needed for Blackwood Creek. Silviculture Resource Extraction Hydromodification Streambank Modification/Destabilization Erosion/Siltation Atmospheric Deposition Natural Sources Nonpoint Source Phosphorus 5.9 Miles 2008 Phosphorus loading from creek to be addressed during development of Lake Tahoe TMDL, but a more specific TMDL for creek may be needed. Grazing-Related Sources Silviculture Resource Extraction Hydromodification Streambank Modification/Destabilization Erosion/Siltation Natural Sources Nonpoint Source Page 1 of 26 2006 CWA SECTION 303(d) LIST OF WATER QUALITY LIMITED SEGMENTS REQUIRING TMDLS LAHONTAN REGIONAL WATER QUALITY CONTROL BOARD USEPA APPROVAL DATE: JUNE 28, 2007 CALWATER POTENTIAL ESTIMATED PROPOSED TMDL REGION TYPE NAME WATERSHED POLLUTANT/STRESSOR SOURCES SIZE AFFECTED COMPLETION Sedimentation/Siltation 5.9 Miles 2008 Creek affected by past gravel quarry operations and other watershed disturbance including grazing and timber harvest.