UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spreckels Mansion

THE SPRECKELS MANSION HISTORIC BEACH HOME At the time the house was built in the early 20th century, most of the homes being built in Coronado were Victorian-style architecture, constructed out of wood with an ornate design. At the time John D. Spreckels built his beach house, a mix of humble Italian Renaissance Revival and Beaux-Arts architectural styles, it stood in stark contrast to the neighboring homes. Today, it is one of the city’s few remaining examples possessing the distinctive characteristics of construction using reinforced concrete that has not been substantially altered. The 17,990 square-foot compound—nearly one-half acre, built on three contiguous 6,000 square-foot lots, includes a main house, a guest house and caretakers living quarters for a total of 12,750 square feet with a total of nine bedrooms, eight full bathrooms and three half bathrooms. The 6,600 square-foot main house originally featured six bedrooms, a Main House 1940’s basement and an attic has been modernized and restored to its turn of the century charm. A semi-circle drive fronted the home, while a central pergola was built atop the flat red-tiled roof as a third floor—an ideal setting to view the After recent restoration of the most historic home of Coronado, it retains Pacific Ocean. The smooth, cream-colored stucco façade completed the the most commanding vista on the island taking in America’s most Italian Renaissance look. The symmetrical appearance was further beautiful beach, the Coronado Islands, Point Loma, and romantic sunsets enhanced by chimneys at both ends of the home’s two adjoining wing. -

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson the Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER of EVERYTHING

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER OF EVERYTHING JACOB ADLER and ROBERT M. KAMINS Open Access edition funded by the National En- dowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non- commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copy- righted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824883669 (PDF) 9780824883676 (EPUB) This version created: 5 September, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1986 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Thelma C. Adler and Shirley R. Kamins In Phaethon’s Chariot … HAETHON, mortal child of the Sun God, was not believed by his Pcompanions when he boasted of his supernal origin. He en- treated Helios to acknowledge him by allowing him to drive the fiery chariot of the Sun across the sky. Against his better judg- ment, the father was persuaded. The boy proudly mounted the solar car, grasped the reins, and set the mighty horses leaping up into the eastern heavens. For a few ecstatic moments Phaethon was the Lord of the Sky. -

DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial

State of California & The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # DISTRICT RECORD Trinomial Page 1 of 32 *NRHP Status Code *Resource Name or # (Assigned by recorder) Potrero Point Historic District D1. Historic Name Potrero Point/Lower Potrero D2. Common Name: Central Waterfront *D3. Detailed Description (Discuss coherence of the district, its setting, visual characteristics, and minor features. List all elements of district.): The Potrero Point Historic District (also referred to as the Central Waterfront) is located in the Potrero Hill district of San Francisco on the western side of San Francisco Bay in the City of San Francisco between Mission Creek on the north and Islais Creek to the south. The approximately 500-acre area is more precisely described as a roughly rectangular district bounded by Sixteenth Street to the north, San Francisco Bay to the east, Islais Creek to the south, and U.S. Interstate 280 to the west. The area measures approximately 1.3 miles from north to south, and approximately 0.6 miles wide from east to west. (See Continuation Sheet, Pg. 2) *D4. Boundary Description (Describe limits of district and attach map showing boundary and district elements.): The Potrero Point (Central Waterfront) area is enclosed within a rectangle formed by the following streets and natural features: Beginning at the northwest corner of Pennsylvania and Sixteenth streets, the northern boundary of the area extends east along Sixteenth Street into San Francisco Bay. The boundary turns ninety degrees and heads south through the bay encompassing the entirety of Piers 70 and 80. At Islais Creek Channel, the boundary makes a ninety degree turn and heads west along the southern shore of the channel. -

Lots for Salei

'' ' g n THE PACIFIC COMMERCIAL ADKHTISKR: .HONOLULU; DECEMBER 2 1900 LlMiTPr. OF HAWAII. LTD. Incorporated MSy!lSK V under th territory ot ot wHWfe!? &1L . Capital, $250,000. PAID IIP rAn.-r.- :,,AL-5600,- 0 President Cecil Brown RESERVE Vice President M. P. Robinson UNDIVDED Cashier w. rw.no PROHTS. io8' ... a OFFICER Q tx-- Principal Office: Tort, near Merchant " u nTnw, Street. Charles M. Col Branoh Office: Hilo, v- Hawaii. -. n. t.OQKe "-- Tei . Business was particularly lively it would be on account of her Atherton ab'sV.;:- '- cq shortcomings in respect. iCiSacisaGfCEralBaiitiiiEBisiflEss .Henry Waterhou.: " W along the waterfront yesterday as ihe this May. Others s.ay that she is easily handled AT HONOLULU Macfarlane, E. n Tenney. 1 of or nothing-havin- AND HLLO. Candless. J. a. result little been in ballast or with a full load and that done on the day previous, Christmas she is to defy the elements Solicits the I built HAviwua DEPOSITS received and Porations. Trusts, day. through a long and prosperous careor. nterest allowed r yearly deposits at lffj.i upon or per Those Island steamers in the habit of There is one point which all me raie cent per annum. business. connecSft, to nautical men, who have viewed the Rules and of Bavings de departing on their regular runs en partment -- bark, agree, and that is that the Kaiu-la- ni furnish d upon application For New Year's Tuesday waited until yesterday, when can give many an older and more a in- away they got to the other islands, famous vessel cards and spades at Fail- nn "PARTMENT rdinarv ' tending to hustle, most of them, to gt ing with a fair wind. -

The Suburbanization of Manufacturing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850-1940

INDUSTRY BUILDS OUT THE CITY: THE SUBURBANIZATION OF MANUFACTURING IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA, 1850-1940 By Richard A. Walker Department of Geography University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected] Published version (with maps) in The Manufactured Metropolis edited by Robert Lewis Temple University Press 2004 pp. 92-123 ANYONE MAY DOWNLOAD AND USE THIS PAPER WITH THE USUAL COURTESY OF CITATION. COPYRIGHT 2004. 2 ABSTRACT The San Francisco Bay Area provides a clear example of industrial dispersal creating the sprawling form of the American metropolis. Neither change in transport modes nor residential suburbanization is principally responsible for shaping the outward spiral of urbanization. Manufacturing began its outward march from the outset of the city’s industrialization, establishing peripheral nodes of employment and working class residence within San Francisco, then beyond the city limits in South San Francisco and especially the East Bay. The primary cause of decentralization has been industrial shifts, or the outbreak of new activities in new places; these have normally taken the form of industrial districts, at various spatial scales. A second cause has been the orchestration of development by business leaders through property ownership and political maneuvering guided by a general vision of metropolitan expansion (whether in cooperation or competition with one another). List of Figures 1. Bay Area manufacturing (employment & output), 1860-1940 2. Bird’s eye view of San Francisco -- lithograph by Currier & Ives, c. 1880 3. Schematic map of industrial zones of San Francisco, c. 1890 4. Bird’s eye view of Bay Area -- San Francisco Daily Commercial News, c. -

Received Omb No

1137 N PS FORM 10-900 RECEIVED OMB NO. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior JUL - 6 2004 National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES OHP REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 1 6A). Complete each item by marking "X" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1 . Name of Property historic name: Gate Park other names/site number: N/A 2. Location street & number: Bounded by Fulton St., Stanyan St., Fell St., Baker St., Oak St., Lincoln Way, and The Great Highway not for publication: N/A city or town: San Francisco vicinity: Sunset and Richmond Districts state: California code: CA county: San Francisco code: 075 zip code: 94117 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority und er the National Historic P reservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request fa r determination of eligibil ity meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National fiteoister of Historic PI; ices ahdfmeets the proce dural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The House That Vicente Built and Some Aptos History by Allen Collins

The House That Vicente Built and Some Aptos History by Allen Collins n 1855, for his twentieth birthday, Vicente Castro’s father gave him 700 Who was Vicente Castro? I acres of land north of today’s Aptos Vicente Castro’s great-grandfather, Joaquín Village. He built his first home on the Ysidro Castro, was one of the twenty-eight, southern tip of his land, between the steep soldiers of the Spanish Army who trekked, banks of Trout and Valencia Creeks. He with his wife and eight children, from Tubac, married Jesus Fuentes in 1858. She died of Mexico, to San Francisco, California, in 1776. pneumonia in that home six years later, Joaquín was part of the historically famous shortly after their third son was born. Anza Party, 240 brave souls, determined to A few months before Vicente’s second settle Alta California. marriage, to Vicenta Pico in 1867, he started a Vicente’s grandfather, José Joaquín long program of selling-off selected parcels of Castro, was five or six years old when he the land his parents had given him. A week trekked with his parents to California in 1776. after his second marriage, he purchased from José Joaquin was granted Rancho San Andres his parents a seven plus acre apple orchard in 1833, a Mexican land grant of nearly across the Coast Road (Soquel Drive) from 9,000-acres along the Santa Cruz County today’s Rancho Del Mar Shopping Center. coast extending from north of La Selva Beach Vicenta Castro came from a huge to near Watsonville. -

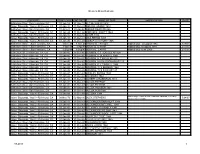

Western Ships Built List SHIPYARD START DATE END DATE NAME OF

Western Ships Built List SHIPYARD START DATE END DATE NAME OF SHIP MODIFICATION DATE Bethlehem Steel--San Francisco, CA 01-Jan-18 31-Dec-18 A C BEDFORD 1918 Kaiser Shipyards, Yard 2--Richmond, CA 01-Jan-43 31-Dec-43 ABIGAIL ADAMS 1943 Bethlehem Steel--San Francisco, CA 01-Oct-41 30-Apr-42 ABNER READ DD-526 Kaiser Shipyards, Yard 2--Richmond, CA 01-Jan-44 31-Dec-44 ABRAM S HEWITT 1944 Bethlehem Steel--San Francisco, CA 01-Jan-16 31-Dec-16 ACME 1916 Kaiser Shipyards, Yard 2--Richmond, CA 01-Jan-44 31-Dec-44 ADA REHAN 1944 Kaiser Shipyards, Yard 2--Richmond, CA 01-Jan-45 31-Dec-45 ADELPHI VICTORY 1945 Bethlehem Steel -- San Francisco, CA 1-Dec-47 1-Dec-48 ADM D.W. TAYLOR Added ship - scrapped 1974 2/17/11 Bethlehem Steel -- San Francisco, CA 1-Apr-48 1-Apr-49 ADM F.B. UPHAM Added ship -scrapped 1984 2/17/11 Bethlehem Steel -- San Francisco, CA 1-Sep-44 1-Sep-45 ADM W.L. CAPPS Added ship -sunk 2000 2/17/11 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-45 31-Dec-45 ADMIRAL C F HUGHES AP-124 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-45 31-Dec-45 ADMIRAL E W EBERLE 1945 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-45 31-Dec-45 ADMIRAL H T MAYO AP-125 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-45 31-Dec-45 ADMIRAL HUGH RODMAN AP-126 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-44 31-Dec-44 ADMIRAL R E COONTZ 1944 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-44 31-Dec-44 ADMIRAL W S BENSON 1944 Bethlehem Steel--Alameda, CA, CA 01-Jan-45 31-Dec-45 ADMIRAL W S SIMS AP-127 Kaiser Shipyards, Yard 2--Richmond, CA 01-Jan-43 31-Dec-43 ADOLPH SUTRO 1943 Kaiser Shipyards, Yard -

The History and Significance of the Adolph Sutro Historic District: Excerpts from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form Prepared in 2000

The History and Significance of the Adolph Sutro Historic District: excerpts from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form prepared in 2000. James P. Delgado Denise Bradley Paul M. Scolari Stephen A. Haller I. SIGNIFICANCE The area located on point Lobos and Lands End overlooking the Pacific Ocean in the westernmost portion of San Francisco has since the 1850s been developed and used by San Franciscans and visitors to the city to experience the scenery and recreational opportunities associated with the shoreline, beach, and ocean. Characteristics of this cultural landscape have combined activities related to the natural features of the area — scenic panoramic views, access to the beach and ocean for hiking and swimming, opportunities to see plant and animal communities — with “tourist” activities — restaurants, swimming, museums, buying souvenirs, and “having been there.” The foundation of this cultural landscape has always been the natural features — ocean, beach, cliffs, views, plant materials, animal life, and the sites, sounds, smells of the ocean. These have provided the reasons that people wanted to come to site and have wanted to shape it to reflect recreational attitudes of the specific time. Through the years the landscape has evolved, specific structures built to provide recreational- related activities have come and gone or changed, but the Sutro Historic Landscape District continues to be a vital place for San Franciscans and regional, national, and international visitors to the city to come and do all the things people have always done in this landscape by the sea. The Sutro Historic Landscape District is located just west of the Golden Gate, on a dramatic promontory overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where the rugged Point Lobos coastline turns abruptly south. -

Bourdette Building 90-92 Second Street / 600-600½ Mission Street

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Bourdette Building 90-92 Second Street / 600-600½ Mission Street Initiated by the Historic Preservation Commission, July 1, 2015 Approved by the Board of Supervisors, May 10, 2016 Signed by Mayor Edwin M. Lee, May 20, 2016 City and County of San Francisco Planning Department Landmark No. Edwin M. Lee, Mayor John Rahaim, Director 271 Cover: View of fires from Nob Hill, April 18, 1906 (upper left); Bourdette Building amid the ruins, May 15, 1906 (right); Bourdette Building 1929 (lower left). Sources: Bancroft Library and California Historical Library The Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) is a seven-member body that makes recommendations to the Board of Supervisors regarding the designation of landmark buildings and districts. The regulations governing landmarks and landmark districts are found in Article 10 of the Planning Code. The HPC is staffed by the San Francisco Planning Department. CONTENTS OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 BUILDING DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Ground Floor Commercial Spaces ........................................................................................................................ 5 Second Story ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Claus Spreckels: a Biographical Case Study of Nineteenth-Century American Immigrant Entrepreneurship

Claus Spreckels: A Biographical Case Study of Nineteenth-Century American Immigrant Entrepreneurship Uwe Spiekermann Claus Spreckels (1828–1908) was perhaps the most successful German-American immigrant entrepreneur of the late nineteenth century. The career of the ―sugar king‖ of California, Hawaii, and the American West consisted of building and breaking monopolies in sugar, transport, gas, electricity, real estate, newspapers, banks, and breweries. This essay uses a biographical approach to discuss central questions of American immigrant entrepreneurship. First, it analyzes the family and ethnic background of Spreckels‘ business. Second, it examines the business development of his widespread investments. Finally, it discusses the significance of Spreckels‘ immigrant status and experience for his successful career. Claus Spreckels was perhaps the most successful German-American immigrant entrepreneur of the late nineteenth century.1 When the self- made man unofficially retired in 1905, his estate was valued at approximately $50 million. The ―sugar king‖ of Hawaii and the West was one of the ten richest Americans of his time. In 1998, he was ranked 1 Whether Frederik Weyerhaeuser was even more successful is still an open question. See Michael Klepper and Robert Gunther, The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present (Secaucus, N.J., 1996) or—with different information—―Fr. Weyer- haeuser, Lumber King, Dead,‖ New York Times, 5 April 1914. Similarly, Spreckels‘ fortune was often overestimated. See Thomas William Herringshaw, ―Claus Spreckels,‖ in Herringshaw, The Biographical Review of Prominent Men and Women of the Day (Chicago, 1889), 491-92, at 491, who speculated about an estate of from one to two hundred million dollars. -

Argonaut Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society

J OURNAL OF THE S AN F RANCI O S C M U S E M AND H I ORICAL S T S OCIETY V OL . 31 31 . N O . 1 . Volume 31 No. 1 Summer 2020 THE ARGONAUT Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles A. Fracchia EDITOR Lana Costantini PHOTO AND COPY EDITOR Lorri Ungaretti GRapHIC DESIGNER Romney Lange PUBLIcatIONS COMMIttEE Hudson Bell Lee Bruno Lana Costantini Charles Fracchia John Freeman Chris O’Sullivan David Parry Ken Sproul Lorri Ungaretti BOARD OF DIREctORS John Briscoe, President Tom Owens, Vice President Kevin Pursglove, Secretary Jack Lapidos,Treasurer Joe Barkett Chris O’Sullivan Rodger Birt David Parry Noah Griffin Christopher A. Patz Richard S. E. Johns Edith L. Piness, Ph.D. Brent Johnson Darlene Plumtree-Nolte Rick Lenat Adriene Roche Robyn Lipsky Ken Sproul Bruce M. Lubarsky Paul J. Su James Marchetti Diana Whitehead Charles A. Fracchia, Founder & President Emeritus of SFHS DIREctOR OF EDUcatION AND PUBLIcatIONS Lana Costantini CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER Darlene Plumtree-Nolte The Argonaut is published by the San Francisco Historical Society, P.O. Box 420470, San Francisco, CA 94142-0470. Changes of address should be sent to the above address. Or, for more information call us at 415.537.1105. TA FC BLE O ONTENTS THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE GERMAN-SPEAKING COMMUNITY in San Francisco, 1850–1924 by Stefanie E. Williams ..........................................................................................................................6 SUTRO’S SAN FRANCISCO— What’s Left? by William R. Huber ...........................................................................................................................52 WORLD WAR I AND THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO by Alan Ziajka ......................................................................................................................................72 Cover photo: Adolph Sutro.