Magic Realism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-Notes on the Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita Author unknown e-Notes on The Master and Margarita From the archive section of The Master and Margarita http://www.masterandmargarita.eu Webmaster Jan Vanhellemont Klein Begijnhof 6 B-3000 Leuven +3216583866 +32475260793 Table of Contents 1. Master and Margarita: Introduction 2. Mikhail Bulgakov Biography 3. One-Page Summary 4. Summary and Analysis 5. Quizzes 6. Themes 7. Style 8. Historical Context 9. Critical Overview 10. Character Analysis 11. Essays and Criticism 12. Suggested Essay Topics 13. Sample Essay Outlines 14. Compare and Contrast 15. Topics for Further Study 16. Media Adaptations 17. What Do I Read Next? 18. Bibliography and Further Reading 1. INTRODUCTION The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov is considered one of the best and most highly regarded novels to come out of Russia during the Soviet era. The book weaves together satire and realism, art and religion, history and contemporary social values. It features three story lines. The main story, taking place in Russia of the 1930s, concerns a visit by the devil, referred to as Professor Woland, and four of his assistants during Holy Week; they use black magic to play tricks on those who cross their paths. Another story line features the Master, who has been languishing in an insane asylum, and his love, Margarita, who seeks Woland's help in being reunited with the Master. A third story, which is presented as a novel written by the Master, depicts the crucifixion of Yeshua Ha-Notsri, or Jesus Christ, by Pontius Pilate. Using the fantastic elements of the story, Bulgakov satirizes the greed and corruption of Stalin's Soviet Union, in which people's actions were controlled as well as their perceptions of reality. -

Narrative Structure in Literature

ELA Virtual Learning English II April 27, 2020 English II Lesson: April 27, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: ● I can analyze how an author’s choices in story structure impact the reader. BELL RINGER The night was calm, but a storm -- full of Timing is everything, especially when it rain and budding anger -- began to swell A in the distance. comes to writing and storytelling. But what if your timing is off? John felt excited. Afterall, it was his B sixteenth birthday. Take a look at the story details to the left. Place the lettered sections in order from Mrs. Peabody saw him snake through the lowest point of tension to the highest and yard from her kitchen window. And that’s answer the prompt below in a quick write: what she told police during the missing C ● Why does this order create the most amount person investigation. of tension? Explain. John was grounded, but snuck out the back door. The door’s creak seemed D louder than a siren. BELL RINGER ANSWER KEY (Answers will vary) John felt excited. Afterall, it was his Our story begins with a character, likely our protagonist, named sixteenth birthday. John. We learn it’s his 16th birthday, a milestone for many B teenagers but not a whole lot of tension so it may come first. John was grounded, but snuck out the Looks like John has gotten himself into trouble in the past and the back door. The door’s creak seemed tension rises a bit because he is breaking the rules. D louder than a siren. -

AESTHETIC PERSPECTIVE in POETRY FILM: a STUDY of CHARLES BUKOWSKI’S “BLUEBIRD” POEM and ITS VISUAL FORM ADAPTATION by MICHAT STENZEL Abeer M

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.6, No.9, pp.54-70, September 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) AESTHETIC PERSPECTIVE IN POETRY FILM: A STUDY OF CHARLES BUKOWSKI’S “BLUEBIRD” POEM AND ITS VISUAL FORM ADAPTATION BY MICHAT STENZEL Abeer M. Refky M. Seddeek1, Amira Ehsan (PhD)2 1Associate Professor, Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport (AASTMT), P.O. Box: 1029, Gamal Abdel Nasser Avenue, Miami, Alexandria, Egypt 2College of Language and Communication (CLC), Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport (AASTMT), P.O. Box: 1029, Gamal Abdel Nasser Avenue, Miami, Alexandria, Egypt ABSTRACT: This paper is divided into two parts; the first aims at investigating how poetry film fuses spoken word poetry with visual images and sound to create meanings, connotations and associations stronger than those produced by each genre on its own. The paper studies the stream of consciousness flow of images and nonlinear narrative style as the main features of that genre in addition to the editing/montage aesthetics and the spatio-temporal continuity. It also highlights William Wees’ notion that in the cinema the union of words and images strengthens the film’s ties to realism and sheds light on the Russian film-director Andrei Tarkovsky who developed the filming strategy poetic logic and made poetry assert the potential of the cinematic image as a form of artistic expression. In the second part the paper explores Charles Bukowski’s poem “Bluebird” (1992) and Michat Stenzel’s short film “Bluebird” (2017) by analyzing the verbal and visual forms to prove whether the filmmaker has succeeded in transferring the poet’s message and feelings or not through various tools and techniques. -

Alexis Wright's Carpentaria and the Swan Book

Exchanges: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal Climate Fiction and the Crisis of Imagination: Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria and The Swan Book Chiara Xausa Department of Interpreting and Translation, University of Bologna, Italy Correspondence: [email protected] Peer review: This article has been subject to a Abstract double-blind peer review process This article analyses the representation of environmental crisis and climate crisis in Carpentaria (2006) and The Swan Book (2013) by Indigenous Australian writer Alexis Wright. Building upon the groundbreaking work of environmental humanities scholars such as Heise (2008), Clark (2015), Copyright notice: This Trexler (2015) and Ghosh (2016), who have emphasised the main article is issued under the challenges faced by authors of climate fiction, it considers the novels as an terms of the Creative Commons Attribution entry point to address the climate-related crisis of culture – while License, which permits acknowledging the problematic aspects of reading Indigenous texts as use and redistribution of antidotes to the 'great derangement’ – and the danger of a singular the work provided that the original author and Anthropocene narrative that silences the ‘unevenly universal’ (Nixon, 2011) source are credited. responsibilities and vulnerabilities to environmental harm. Exploring You must give themes such as environmental racism, ecological imperialism, and the slow appropriate credit violence of climate change, it suggests that Alexis Wright’s novels are of (author attribution), utmost importance for global conversations about the Anthropocene and provide a link to the license, and indicate if its literary representations, as they bring the unevenness of environmental changes were made. You and climate crisis to visibility. -

"WHAT IS a SECT?" in EAST WEST Perspectivel Edward G

THE SECTARIAN IN US. QUESTIONS ON THE QUESTION "WHAT IS A SECT?" IN EAST WEST PERSPECTIVEl Edward G. Farrugia, SJ Until before Vatican II the answer to the question what a sect is seemed to present, for many in the Catholic Church, no special difficulties. Whoever cut himself or herself off from the one true Church belonged, in ascending order of distance from the one true Church, to one of three categories: a) schismatics, b) heretics or c) sects. Schismatics had basically rescinded only communion while practically retaining the whole truth; heretics, while giving up some basic truths, had kept many others; and sects ];lad disfigured the truth to such an extent that they could hardly claim to be Christians any longer, in spite of some Christian elements in their new beliefs and could be described as a Christian sect primarily in view of the Christian Church from which they broke off. o. Formulating the problem Our concern here is to formulate a problem in view of a dogmatic aspect which has been insufficiently discussed - sects considered not in thems<:?lves, but insofar as they provide elements for a differentiation between East and West. Given such a methodological self-restriction, it cannot be the purpose of this brief contribution to discuss so many studies on the theme, much less so regarding the question of the definition of sect. The study of L. Greenslade, Schism in the Early Church: What light can the past throw? (London 1984) could here be mentioned, as representative. I. Abbreviations: ALGERMISSEN =K. Algermissen, Konfessionskunde, (Revised by H. -

УДК 81.33 an ARTISTIC IMAGE METAPHORICITY: CULTURAL MEMORY and TRANSLATION V.A. Razumovskaya, E.B. Grishaeva . Abstract the A

УДК 81.33 AN ARTISTIC IMAGE METAPHORICITY: CULTURAL MEMORY AND TRANSLATION V.A. Razumovskaya, E.B. Grishaeva . Abstract The article presents a complementary semantic-semiotic analysis of an artistic image in the framework of a literary text. The analysis is followed by post-translation descriptions. Being generated and functioning within a literary text an artistic image is considered to be an extended metaphoric formation primarily destined to fulfill the aesthetic function. Particular attention is paid to the cultural information and memory embodied in a unique cultural code presented in an artistic image and closely connected with its metaphoric characteristics. The present research was conducted on the material of the “strong” text of the Russian culture – “The Master and Margarita” by M. Bulgakov. The artistic image of Bulgakov’s tom-cat Behemoth is a heterogeneous metaphoric formation combining the cultural memory of a Biblical monster Behemoth, zoo-metaphorical characteristics of a hippopotamus (as a real fauna representative) and various connotations of a black tom-cat in its real and mythological hypostases. The research methodology assumes integrated analysis combining mythopoetic, hermeneutic and comparative methods. In the situation of literary translation, a literary image can be considered as a regular unit of translation, the reconstruction of which in “other” languages and cultures requires special translator’s decisions and application of effective translation techniques and strategies. Keywords: “Strong” text; artistic image; cultural information and memory; cultural code; metaphor; aesthetic effect; intertextuality; “The Master and Margarita”; Behemoth; cognitive equivalence. Introduction Any literary text is the unique result of individual perception, image comprehension and artistic reflection of the real or fiction life. -

Profile Winter 03

Volume 15 Number 1 Winter 2003 profileThe Frostburg State University Magazine HOMEGROWN HERO Congressional Medal of Honor Recipient Capt. James A. Graham, ’63 lee teter inside: Frostburg State or Frostbite Falls 14 What does Bullwinkle Moose™ have to do with FSU? Millions of TV viewers recently found out. See “Noted and Quoted.” ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ profile Vol. 15 No. 1 Winter 2003 TM Vice President for University Advancement Gary Horowitz Associate Vice President/ Director of Alumni Programs The Beall Papers Colleen Peterson The official documents of Editor 16 Ty DeMartino U.S. Senators J. Glenn Beall Contributing Writers Sr. and J. Glenn Beall, Jr. Liz Douglas Medcalf, staff writer have come “home” to Frostburg Sara Mullins, staff writer Chris Starke, Sports Information and are now part of the Beall Jack Aylor, FSU Foundation Archives in the FSU Ort Library. Becky Coleman, ClassNotes Kerri Burtner, Alumni/Parent Programs Leatrice Burphy, intern Graphic Design Colleen Stump, FSU Publications Ann Townsell, Homecoming scrapbook Photographers Ty DeMartino “Grounds” for Action Liz Douglas Medcalf An alumna “woke up and smelled Mark Simons 19 the coffee” when she paid back a 50-year-old “loan” to purchase a Profile is published for alumni, parents, friends, campus java urn. faculty and staff of Frostburg State University. Editorial offices are located in 228 Hitchins, FSU, 101 Braddock Road, Frostburg, MD 21532-1099. Office of University Advancement: 301/687-4161 Office of Alumni Programs: 301/687-4068 FAX: 301/687-4069 Frostburg State University is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity institution. Admission as well as all policies, programs and activities of the University are determined without regard to race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age or handicap. -

Mikhail Bulgakov's the Master and Margarita Vladimir Lakshin

Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita Vladimir Lakshin In the essay that follows, Lakshin presents an overview of The Master and Margarita and the novel's place in modern Russian literature Published in Twentieth-Century Russian Literary Criticism, edited by Victor Erlich, pp. 247-83. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1975. From the archive section of The Master and Margarita http://www.masterandmargarita.eu Webmaster Jan Vanhellemont Klein Begijnhof 6 B-3000 Leuven +3216583866 +32475260793 Where there is no love of art, there is no criticism either. " Do you want to be a connoisseur of the arts ?" Winckelmann says. " Try to love the artist, look for beauty in his creations. " Pushkin 1 On a strange, fantastic moonlit night after Satan's Ball when Margarita is united with her beloved by the power of magic charms, the omnipotent Woland asks the Master to show him his novel about Pontius Pilate. The Master is in no position to do this. He has burned his novel in the stove. "This cannot be," retorts Woland. "Manuscripts don't burn." And at that moment the cat, holding in his paws a thick manuscript, offers Messire with a bow a neat copy of the destroyed book. "Manuscripts don't burn" Mikhail Bulgakov died with this belief in the stubborn, indestructible power of art, at the time when all his major works lay unpublished in his desk drawers only to reach the reader one at a time after a quarter of a century. "Manuscripts don't burn"--these words served the author as an incantation against the destructive work of time, against the dismal fate of his last and, to him, most precious work, the novel The Master and Margarita. -

Introducing I-Docs to Geography: Exploring Interactive Documentary’S Nonlinear Imaginaries

1 Introducing i-Docs to Geography: Exploring interactive documentary’s nonlinear imaginaries Abstract This paper introduces interactive documentaries, or i-Docs, to Geography through an analysis of one i-Doc; Gaza Sderot. Interactive Documentary is an increasingly popular documentary form. I-Docs are defined by ‘nonlinear’ spatiotemporal organisation as their interactive capacities enable multiple pathways through documentary footage and materials. It is often argued that this nonlinearity is politicized by i-Docs to enable polyvocality and the destabilisation of dominant narratives. I argue that i-Docs deserve Geographical attention for two key reasons. Firstly, if Geographers have long explored articulations and reformulations of space-time through media then i-Docs offer an insight into contemporary constructions of nonlinear spatiotemporal imaginaries through interactive medium. Secondly, nonlinearity and its politics has also become foundational to Geography’s own approaches to space-time, making pertinent the explorations of nonlinearity and its socio-political implications that engagement with i-Docs enables. In this context, I analyse Gaza Sderot to explore its construction of a nonlinear spatiotemporal imaginary and question the political perspectives that imaginary generates for its subject of the Gaza conflict. In concluding, I also suggest that i-Docs could be a valuable methodological tool for Geographers. Key Words: Interactive Documentary, Nonlinearity, Space-time, Gaza Sderot, Imaginaries, Politics 2 Introduction Interactive documentary is a new form of documentary that is swiftly gaining prominence. I- Docs can take many digital forms but are defined by their ‘nonlinear’ spatiotemporal organisation and interactive capacities. Rather than presenting footage in a predetermined order, i-Docs offer collections of material such as video clips and still images which users can navigate in various ways. -

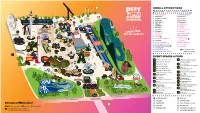

Map of Playland

RIDES & ATTRACTIONS ■ Extreme Rides ■ Kids & Family Rides ■ Attractions 1 Westcoast Wheel 22 Haunted Mansion* 2 Pirate Ship 23 Hell’s Gate 3 Crazy Beach Party 24 Dizzy Drop 4 Atmosfear 25 Drop Zone* ATM 5 Music Express 26 Revelation* 6 Gladiator 27 Bug Whirled 7 Breakdance 28 Choppers 8 Enterprise 29 Teacups 9 Glass House 30 Merry-Go-Round SHARE YOUR 10 Hellevator 31 Flutterbye 11 Rock-N-Cars 32 Honeybee Express #PLAYLANDPICS 12 Scrambler 33 Face Painting* 13 Flume 34 Kettle Creek 14 Tats Temporary Tattoos* Mine Coaster 15 The Beast 35 Cap’n KC 16 Sea-to-Sky Swinger 36 Balloon Explorers 17 Pacific Adventure Golf 37 Cool Cruzers 18 Wooden Roller Coaster 38 Super Slide 19 Climbing Wall 20 Play Quarters Arcade* Ride Photo Available ATM 21 Bonanza Shooting Gallery* *Additional Charge EVENT SPACES & FOOD A Kettle Creek Events Tent M Candy & Snack Concession Candy apples, candy floss, popcorn, B Atmosfear Events Tent sno-cones, cold drinks C Flume Picnic Area N Coaster Dogs Gourmet hot dogs with tons of toppings D Lagoon Picnic Area O Triple O’s E Ride Side Event Area Fresh burgers, chicken strips & hand-scooped shakes F FunDunkers Mini Donuts NPQR STUV Unforgettable mini donuts & churros P Fresh Squeezed Lemonade The real thing G What the Fudge ATM Fudge & sweets Q BeaverTails Classic Canadian pastry & poutine H Gone Fishing R Cheese Please British-style Oceanwise fish & chips Grilled cheese sandwiches I Scoops S Honeybee Express Hand-made waffle cones, ice cream & shakes Candy & snacks J Candy Shoppe T Buen Gusto Tacos & Totchos Fun & fancy -

Ambiguity and Meaning in the Master and Margarita: the Role of Afranius

ARTICLES RICHARD W. F. POPE Ambiguity and Meaning in The Master and Margarita: The Role of Afranius Perhaps the most mysterious and elusive figure in Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita1 is Afranius, a man who has been in Judea for fifteen years working in the Roman imperial service as chief of the procurator of Judea's secret police. He is present in all four Judean chapters of the novel (chapters 2, 16, 25, 26) as one of the myriad connecting links, though we really do not know who he is for certain until near the end of the third of these chapters, "How the Procurator Tried to Save Judas of Karioth." We first meet him in chapter 2 (which is re lated by Woland and entitled "Pontius Pilate") simply as "some man" (kakoi-to chelovek), face half-covered by a hood, in a darkened room in the palace of Herod the Great, having a brief whispered conversation with Pilate, who has just finished his fateful talk with Caiaphas (E, p. 39; R, pp. 50-51). Fourteen chapters later, in the chapter dreamed by Ivan Bezdomnyi and entitled "The Execution" (chapter 16), we meet him for the second time, now bringing up the rear of the convoy escorting the prisoners to Golgotha and identified only as "that same hooded man with whom Pilate had briefly conferred in a darkened room of the palace" (E, p. 170; R, p. 218). "The hooded man" attends the en tire execution sitting in calm immobility on a three-legged stool, "occasionally out of boredom poking the sand with a stick" (E, p. -

E Shadows of Imberfewon a Study of Self-Reflexivitv Iman Rushdie's

e Shadows of ImberfeWonem .* . œ A study of Self-reflexivitv 1n R. K. Npyan9sThe Taslima Nasrin's Lq~a.m. ad Sa Iman Rushdie's Midnipht 's Children Apma V. Zambare Thesis Submitted in partial hilfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Atts (English) Acadia University Fall Convocation 1999 O by Apama Vasant Zambare, 1999 I, Aparna V. Zambare, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan, or distrubute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. Signature of Author Date II Chapter I - Introduction ------------ 1 III Chapter II - A Precursor of Self-reflexivity: R. K. Narayan's The aide -------- 19 IV Chapter III - The Imitation of Non-Literary Discourse An Analysis of Taslima Nasrin's Laja ---- 42 V Chapter - N The Chutnification of Narrative Salrnan Rushdie's Midnight S Children ------ 66 VI Chapter - V Conclusion ------------ 93 This thesis aims at examinhg the complex narrative mode of self-reflexivity, ascertainhg how it senes the postcolonial agenda of destabilizing the power of Eurocentric lit- discourse, the discourse that marginalized Literary traditions of subject peoples. Denved fiom mcient literary traditions, self-reflexive narrative asserts the cul- identity of colonized societies. In particular, this thesis focuses on three self- reflexive novels fiom the indian subcontinent: R. K. Narayan's The Guide, Taslima Nasrin's LuJa, and Salman Rushdie's Midnight 's Children. The self-reflexive techniques employed in each of these narratives Vary a great deal. Narayan's nte Guide is modeled on various ancient patterns of storytelling and on mythic haditions.