The Study of Bird Migration Across the Western Sahara; a Contribution with Sound Luring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

THE BUG RIVER VALLEY for NATURE LOVERS Eastern Poland with a Difference

THE BUG RIVER VALLEY FOR NATURE LOVERS Eastern Poland with a difference By Olivier Dochy, Belgium From 21st until 25th of June, I got the chance to join a study visit to the valley of the Bug river on the border of Poland and Belarus, in the far east of Poland. The purpose of this visit was tot evaluate local initiatives for sustainable tourism, oriented to "riverside & country- side" tourism. This visit was organized by a Flemish-Polish exchange project with the prov- inces of West-Vlaanderen en Lubelski (Poland), but also the flemish initiative vzw De Boot (www.deboot.be). My task was to evaluate which topics in the region could be interesting for nature-lovers in general and keen nature-specialists in particular, such as birders. Well, there is a lot ! It is not like the wild expanses of the well-known Biebrza valley or the untouched forests of Bia- lowieza, but rather a small-scale (agri)cultural landscape. But it still has all the biodiversity that once flourished in Western-Europe and now all (but) disappeared. Here follow a number of tips voor those who want to visit the region. There is a lot of in- formation great and small on the internet about the region, but you have to surf a lot to find it all. Anyway, there certainly is a lot to discover for naturalists with a pioneer drive ! You can find pictures of our visit here: http://picasaweb.google.com/Odee.fotos/BugRiverPoland?feat=directlink 1 WHERE IS IT ? The province of Lubelski is in the extreme east of Poland. -

Spatial Behaviour and Density of Three Species of Long-Distance Migrants Wintering in a Disturbed and Non-Disturbed Woodland in Northern Ghana

Bird Conservation International (2018) 28:59–72. © BirdLife International, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0959270917000132 Spatial behaviour and density of three species of long-distance migrants wintering in a disturbed and non-disturbed woodland in northern Ghana MIKKEL WILLEMOES, ANDERS P. TØTTRUP, MATHILDE LERCHE-JØRGENSEN, ERIK MANDRUP JACOBSEN, ANDREW HART REEVE and KASPER THORUP Summary Changes in land-use and climate are threatening migratory animals worldwide. In birds, declines have been widely documented in long-distance migrants. However, reasons remain poorly under- stood due to a lack of basic information regarding migratory birds’ ecology in their non-breeding areas and the effects of current environmental pressures there. We studied bird densities, spatial and territorial behaviour and habitat preference in two different habitat types in northern Ghana, West Africa. We study three common Eurasian-African songbirds (Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus, Melodious Warbler Hippolais polyglotta and Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca) in a forested site, heavily disturbed by agricultural activities, and a forest reserve with no agriculture. The three species differed in non-breeding spatial strategies, with Willow Warblers having larger home ranges and being non-territorial. Home ranges (kernel density) of the three species were on average 1.5–4 times larger in the disturbed site than in the undisturbed site. Much of the birds’ tree species selection was explained by their preference for tall trees, but all species favoured trees of the genus Acacia. The overall larger home ranges in the disturbed site were presumably caused by the lower density of tall trees. Density of Pied Flycatchers was 24% lower in disturbed habitat (not significantly different from undisturbed) but Willow Warbler density in the disturbed habi- tat was more than 2.5 times the density in undisturbed. -

SB 31(1) TXT 4/2/11 11:14 Page 23

SB 31(1) TXT 4/2/11 11:14 Page 23 Short Notes Tim Harrison, of the BTO Garden Bird Feeding only those using food or water. More participants Survey (GBFS), has commented that there have in the BTO Garden BirdWatch would be partic- only been five gardens in which Common ularly welcome in Scotland www.bto.org/gbw. Crossbills have been observed feeding during the 40 years of the survey. Four of these (in It may be that Common Crossbills are more likely Norfolk, Dorset, Powys and Hertfordshire) are to come to feeders in areas where tree cover is not in Scotland, while the exact location of the scarce or absent. On Shetland, Mike Pennington fifth is unclear. However, as the GBFS is spread notes that they tend to ignore feeders, but in one across the UK, with c. 250 gardens per winter, invasion about 10 years ago, once they had areas in which garden rarities such as Crossbills found his feeder there were up to a dozen daily might be common could be poorly represented. in the garden, with 15 ringed over two days. Participants in the GBFS are recruited from the larger BTO Garden BirdWatch, a year-round survey that records all birds in gardens rather than Observations on Lesser Whitethroat singing and roosting behaviour in Ayrshire during May 2010 The Lesser Whitethroat Sylvia curruca is on the about 1.5–2 seconds and has an interval of north-western edge of its breeding range in about 8 seconds between song bursts, and (b) a Scotland. Observers have commented on the warbling/twittering sub-song, containing many relatively short song period of male birds in soft warbling notes and quiet chattering Scotland which can make censusing this species segments, only audible at a range of less than difficult (see the species account in Forrester et 10 m. -

Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK

Technical Assistance Report Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK - Sapo National Park -Vision Statement By the year 2010, a fully restored biodiversity, and well-maintained, properly managed Sapo National Park, with increased public understanding and acceptance, and improved quality of life in communities surrounding the Park. A Cooperative Accomplishment of USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon- USDA Forest Service May 29, 2005 to June 17, 2005 - 1 - USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Protected Area Development Management Plan Development Technical Assistance Report Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon 17 June 2005 Goal Provide support to the FDA, CI and FFI to review and update the Sapo NP management plan, establish a management plan template, develop a program of activities for implementing the plan, and train FDA staff in developing future management plans. Summary Week 1 – Arrived in Monrovia on 29 May and met with Forestry Development Authority (FDA) staff and our two counterpart hosts, Theo Freeman and Morris Kamara, heads of the Wildlife Conservation and Protected Area Management and Protected Area Management respectively. We decided to concentrate on the immediate implementation needs for Sapo NP rather than a revision of existing management plan. The four of us, along with Tyler Christie of Conservation International (CI), worked in the CI office on the following topics: FDA Immediate -

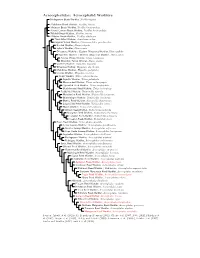

Acrocephalidae Species Tree

Acrocephalidae: Acrocephalid Warblers Madagascan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas typica ?Subdesert Brush-Warbler, Nesillas lantzii ?Anjouan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas longicaudata ?Grand Comoro Brush-Warbler, Nesillas brevicaudata ?Moheli Brush-Warbler, Nesillas mariae ?Aldabra Brush-Warbler, Nesillas aldabrana Thick-billed Warbler, Arundinax aedon Papyrus Yellow Warbler, Calamonastides gracilirostris Booted Warbler, Iduna caligata Sykes’s Warbler, Iduna rama Olivaceous Warbler / Eastern Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna pallida Isabelline Warbler / Western Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna opaca African Yellow Warbler, Iduna natalensis Mountain Yellow Warbler, Iduna similis Upcher’s Warbler, Hippolais languida Olive-tree Warbler, Hippolais olivetorum Melodious Warbler, Hippolais polyglotta Icterine Warbler, Hippolais icterina Sedge Warbler, Titiza schoenobaenus Aquatic Warbler, Titiza paludicola Moustached Warbler, Titiza melanopogon ?Speckled Reed-Warbler, Titiza sorghophila Black-browed Reed-Warbler, Titiza bistrigiceps Paddyfield Warbler, Notiocichla agricola Manchurian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla tangorum Blunt-winged Warbler, Notiocichla concinens Blyth’s Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla dumetorum Large-billed Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla orina Marsh Warbler, Notiocichla palustris African Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla baeticata Mangrove Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla avicenniae Eurasian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla scirpacea Caspian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla fusca Basra Reed-Warbler, Acrocephalus griseldis Lesser Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus gracilirostris Greater Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Skomer Island Bird Report 2017

Skomer Island Bird Report 2017 Page 1 Published by: The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales The Nature Centre Fountain Road Tondu Bridgend CF32 0EH 01656 724100 [email protected] www.welshwildlife.org For any enquiries please contact: Skomer Island c/o Lockley Lodge Martins Haven Marloes Haverfordwest Pembrokeshire SA62 3BJ 07971 114302 [email protected] Skomer Island National Nature Reserve is owned by Natural Resources Wales and managed by The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. More details on visiting Skomer are available at www.welshwildlife.org. Seabird monitoring on Skomer Island NNR is supported by JNCC. Page 3 Table of Contents Skomer Island Bird Report 2017 ............................................................................................................... 5 Island rarities summary 2017 .......................................................................................................................... 5 Skomer Island seabird population summary 2017 .......................................................................................... 6 Skomer Island breeding landbirds population summary 2017 ....................................................................... 7 Systematic list of birds ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Rarity Report ................................................................................................................................................ -

Migration of Birds Circular 16

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migration of Birds Circular 16 Migration of Birds Circular 16 by Frederick C. Lincoln, 1935 revised by Steven R. Peterson, 1979 revised by John L. Zimmerman, 1998 Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS Associate editor Peter A. Anatasi Illustrated by Bob Hines U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE D E R P O A I R R E T T M N EN I T OF THE U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE..............................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................2 EARLY IDEAS ABOUT MIGRATION............................................................4 TECHNIQUES FOR STUDYING MIGRATION..........................................6 Direct Observation ....................................................................................6 Aural ............................................................................................................7 Preserved Specimens ................................................................................7 Marking ......................................................................................................7 Radio Tracking ..........................................................................................8 Radar Observation ....................................................................................9 EVOLUTION OF MIGRATION......................................................................10 -

Migrant Birds and Environmental Change in the Sahel

!"#$% &'(% )*"#+(% "#$% ,-+."#/% 0-.$'% -#% /*(% '"*(!1% !"#"$!%&' (!)"*' + Migrant t 5IF4BIFMJTBOJNQPSUBOUGPSUSBOT4BIBSBONJHSBOUCJSETJOUIF &VSPQFBOXJOUFS.BOZPGUIFTFTQFDJFTBSFJOEFDMJOF Birds and t *OUIF4BIFM CJSETPDDVSPOMBOEJOUFOTJWFMZVTFEGBSNMBOET HSBTTMBOETBOEXPPEMBOET t -BOEVTFJOUIF4BIFMJTDIBOHJOHJOSFTQPOTFUPBXJEFSBOHFPG Environmental TPDJBM FDPOPNJDBOEFOWJSPONFOUBMGBDUPST t 5IFNPTUJNQPSUBOUMBOEVTFDIBOHFTGPSCJSETJOWPMWFDIBOHFT JOUIFFYUFOUPGUSFFTBOETDSVCJOSVSBMMBOETDBQFT5IFJNQBDUT Change in PGMBOETDBQFDIBOHFNBZCFQPTJUJWFPSOFHBUJWFGPSEJòFSFOU TQFDJFT t .PSFSFTFBSDIJTOFFEFEPOUIFJNQBDUTPGMBOEVTFDIBOHFPO the NJHSBOUCJSETJOUIF4BIFM Sahel Over 2 billion songbirds migrate between Europe and Africa1, many concentrating south of the Sahara in the farming and grazing lands of the semi-arid Sahel zone. Migrant birds are exposed to threats in breeding grounds in Europe, on migration, and in their wintering grounds in Africa. Many trans-Saharan migrants are falling in numbers2. It is not know why, but it is widely believed that changes in non-breeding and staging areas in Africa are important. The Sahel is subject to pressure from human-in!uenced climate change and increasingly intensive economic exploitation. There is still limited understanding of the implications of present and future land use change in the Loss of trees and scrub will impact even open country species such as Northern Wheatear (© Paul Hilllion) Sahel for African-Eurasian migrant birds3. Land Use Change in the Sahel There have been profound changes in land use in the Climatic Variability and Birds Sahel in the last four decades. As farmers, livestock keepers It is beyond doubt that Sahel rainfall has a major impact on and other landholders have responded to drought and migrant bird numbers. Rainfall in the Sahel is 200-600mm economic and social change8. per year, and is highly variable between years. There was t Agriculture has extended onto previously uncultivated an intense drought from 1968-74, and another in the early land, and become more intensive (with shorter fallow 1980s. -

Identification of Arabian Warbler

Identification of Arabian Warbler Hadoram Shirihai Illustrated by Alan Harris he Arabian Warbler Sylvia leucomelaena was originally placed in the Tgenus Parisoma. Meinertzhagen (1949), Williamson (1960) and others placed it in the genus Sylvia owing to its morphological similarities to this genus. Afik (1984) was convinced that this was incorrect, however, as its biological characteristics and nesting range differed from other Sylvia species. In the British Museum (Natural History), Tring, I compared the genera Parisoma and Sylvia. I believe that the Arabian Warbler represents a link between these two genera. Morphologically it resembles Parisoma in wing shape, tail-to-wing ratio, and tail pattern; the bill shape, however, is more similar to that of Orphean Warbler S. hortensis. The Arabian Warbler occurs on both sides of the Red Sea—in Arabia, Somalia and Sudan—between the genus Parisoma in Africa and the genus Sylvia in the Palearctic. In the 1960s, it was found to breed in the Arava Valley, Israel (Zahavi & Dudai 1974; Inbar 1977); this is the northernmost limit of its world range. The population in Israel is resident, making only short-distance movements. Three subspecies have been described: S. 1. blanfordi in Sudan, S. I. leucomelaena in Arabia and S. I. somaliensis in Somalia. A comparison between specimens from Israel and those in the British Museum shows the Israeli birds to differ both in plumage and, to a lesser extent, in size from these three races. They are most similar to the Arabian S. I. leucomelaena, but may be isolated from that race and thus may require recognition as a separate subspecies, S.