Spring Passerine Migrants Stopping Over in the Sahara Are Not Fall-Outs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Khalladi-Bpp Anexes-Arabic.Pdf

Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 107 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 108 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 109 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 110 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 111 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 112 Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 113 The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria are intended to be an easily and widely understood system for classifying species at high risk of global extinction. The IUCN Red List is categorized in the following Categories: • Extinct (EX): A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form. Khalladi Windfarm and Power Line Projects 114 Biodiversity Protection Plan, July 2015 • Extinct in the Wild (EW): A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. -

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

Spatial Behaviour and Density of Three Species of Long-Distance Migrants Wintering in a Disturbed and Non-Disturbed Woodland in Northern Ghana

Bird Conservation International (2018) 28:59–72. © BirdLife International, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0959270917000132 Spatial behaviour and density of three species of long-distance migrants wintering in a disturbed and non-disturbed woodland in northern Ghana MIKKEL WILLEMOES, ANDERS P. TØTTRUP, MATHILDE LERCHE-JØRGENSEN, ERIK MANDRUP JACOBSEN, ANDREW HART REEVE and KASPER THORUP Summary Changes in land-use and climate are threatening migratory animals worldwide. In birds, declines have been widely documented in long-distance migrants. However, reasons remain poorly under- stood due to a lack of basic information regarding migratory birds’ ecology in their non-breeding areas and the effects of current environmental pressures there. We studied bird densities, spatial and territorial behaviour and habitat preference in two different habitat types in northern Ghana, West Africa. We study three common Eurasian-African songbirds (Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus, Melodious Warbler Hippolais polyglotta and Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca) in a forested site, heavily disturbed by agricultural activities, and a forest reserve with no agriculture. The three species differed in non-breeding spatial strategies, with Willow Warblers having larger home ranges and being non-territorial. Home ranges (kernel density) of the three species were on average 1.5–4 times larger in the disturbed site than in the undisturbed site. Much of the birds’ tree species selection was explained by their preference for tall trees, but all species favoured trees of the genus Acacia. The overall larger home ranges in the disturbed site were presumably caused by the lower density of tall trees. Density of Pied Flycatchers was 24% lower in disturbed habitat (not significantly different from undisturbed) but Willow Warbler density in the disturbed habi- tat was more than 2.5 times the density in undisturbed. -

Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK

Technical Assistance Report Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK - Sapo National Park -Vision Statement By the year 2010, a fully restored biodiversity, and well-maintained, properly managed Sapo National Park, with increased public understanding and acceptance, and improved quality of life in communities surrounding the Park. A Cooperative Accomplishment of USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon- USDA Forest Service May 29, 2005 to June 17, 2005 - 1 - USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Protected Area Development Management Plan Development Technical Assistance Report Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon 17 June 2005 Goal Provide support to the FDA, CI and FFI to review and update the Sapo NP management plan, establish a management plan template, develop a program of activities for implementing the plan, and train FDA staff in developing future management plans. Summary Week 1 – Arrived in Monrovia on 29 May and met with Forestry Development Authority (FDA) staff and our two counterpart hosts, Theo Freeman and Morris Kamara, heads of the Wildlife Conservation and Protected Area Management and Protected Area Management respectively. We decided to concentrate on the immediate implementation needs for Sapo NP rather than a revision of existing management plan. The four of us, along with Tyler Christie of Conservation International (CI), worked in the CI office on the following topics: FDA Immediate -

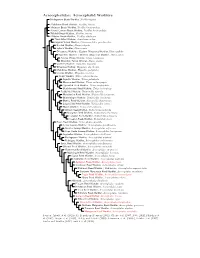

Acrocephalidae Species Tree

Acrocephalidae: Acrocephalid Warblers Madagascan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas typica ?Subdesert Brush-Warbler, Nesillas lantzii ?Anjouan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas longicaudata ?Grand Comoro Brush-Warbler, Nesillas brevicaudata ?Moheli Brush-Warbler, Nesillas mariae ?Aldabra Brush-Warbler, Nesillas aldabrana Thick-billed Warbler, Arundinax aedon Papyrus Yellow Warbler, Calamonastides gracilirostris Booted Warbler, Iduna caligata Sykes’s Warbler, Iduna rama Olivaceous Warbler / Eastern Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna pallida Isabelline Warbler / Western Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna opaca African Yellow Warbler, Iduna natalensis Mountain Yellow Warbler, Iduna similis Upcher’s Warbler, Hippolais languida Olive-tree Warbler, Hippolais olivetorum Melodious Warbler, Hippolais polyglotta Icterine Warbler, Hippolais icterina Sedge Warbler, Titiza schoenobaenus Aquatic Warbler, Titiza paludicola Moustached Warbler, Titiza melanopogon ?Speckled Reed-Warbler, Titiza sorghophila Black-browed Reed-Warbler, Titiza bistrigiceps Paddyfield Warbler, Notiocichla agricola Manchurian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla tangorum Blunt-winged Warbler, Notiocichla concinens Blyth’s Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla dumetorum Large-billed Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla orina Marsh Warbler, Notiocichla palustris African Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla baeticata Mangrove Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla avicenniae Eurasian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla scirpacea Caspian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla fusca Basra Reed-Warbler, Acrocephalus griseldis Lesser Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus gracilirostris Greater Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus -

The Study of Bird Migration Across the Western Sahara; a Contribution with Sound Luring

The study of bird migration across the Western Sahara; a contribution with sound luring Marc Herremans Royal Museum for Central Africa, Leuvensesteenweg 17, 3080 Tervuren, Belgium; e-mail: [email protected] Report of field research in Mauritania during spring and autumn 2003 in association with the Sahara project of the Swiss Ornithological Institute (Vogelwarte Sempach). Abstract During spring and autumn migration 2003, the Swiss Ornithological Institute set up a concerted project in Mauritania to study bird migration across the Sahara (see www.vogelwarte.ch/sahara/). I participated with a side project using artificial induction of landfall with sound luring in an attempt to overcome the potential problem of low sample sizes for random trapping of natural landfall. A comparison with sound lured samples was also expected to provide more insights into the motivation of birds to stop or fly. In total, 9.467 migrants of 55 species were ringed, 590 birds recaptured locally and 49 ringed in Europe were recovered. Sound luring was more effective in autumn, when samples became, however, heavily dominated by Reed Warblers (Acrocephalus scirpaceus) and Garden Warblers (Sylvia borin). In autumn, adults migrated ahead of juveniles, and in Reed and Garden Warblers, most adults travelled over the interior of the Sahara, while juveniles were concentrated along the coast; no such effect was seen in species that avoided the interior (Nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos, Grasshopper Warbler Locustella naevia). Local recapture rates were low (6%), particularly inland in autumn (1%), where many more birds (12%) made longer stopovers in spring. In autumn, there were many more birds in poor condition along the coast than inland; birds in poor condition had much higher recapture rates, and birds in good condition (fat score >3, muscle score=3) rarely made a stopover. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Skomer Island Bird Report 2017

Skomer Island Bird Report 2017 Page 1 Published by: The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales The Nature Centre Fountain Road Tondu Bridgend CF32 0EH 01656 724100 [email protected] www.welshwildlife.org For any enquiries please contact: Skomer Island c/o Lockley Lodge Martins Haven Marloes Haverfordwest Pembrokeshire SA62 3BJ 07971 114302 [email protected] Skomer Island National Nature Reserve is owned by Natural Resources Wales and managed by The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. More details on visiting Skomer are available at www.welshwildlife.org. Seabird monitoring on Skomer Island NNR is supported by JNCC. Page 3 Table of Contents Skomer Island Bird Report 2017 ............................................................................................................... 5 Island rarities summary 2017 .......................................................................................................................... 5 Skomer Island seabird population summary 2017 .......................................................................................... 6 Skomer Island breeding landbirds population summary 2017 ....................................................................... 7 Systematic list of birds ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Rarity Report ................................................................................................................................................ -

Downloaded From

The harmonization of Red Lists for threatened species in Europe Iongh, H.H. de; Banki, O.S.; Bergmans, W.; Van der Werff ten Bosch, M.J. Citation Iongh, H. H. de, Banki, O. S., Bergmans, W., & Van der Werff ten Bosch, M. J. (2003). The harmonization of Red Lists for threatened species in Europe. Leiden: Bakhuijs Publishers. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15728 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15728 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Red List Book oktober. 11/13/03 12:31 PM Pagina 1 THE HARMONIZATION OF RED LISTS FOR THREATENED SPECIES IN EUROPE Red List Book oktober. 11/13/03 12:31 PM Pagina 2 Red List Book oktober. 11/13/03 12:31 PM Pagina 3 The harmonization of Red Lists for threatened species in Europe Proceedings of an International Seminar in Leiden, 27 and 28 November 2002 Editors H.H. de Iongh O.S. Bánki W. Bergmans M.J. van der Werff ten Bosch Mededelingen No. 38 November 2003 Red List Book oktober. 11/13/03 12:31 PM Pagina 4 NEDERLANDSE COMMISSIE VOOR INTERNATIONALE NATUURBESCHERMING Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection Secretariaat: dr. H.P. Nooteboom National Herbarium of the Netherlands/Hortus Botanicus Einsteinweg 2 POB 9514 2300 RA Leiden The Netherlands Mededelingen No. 38, 2003 Editors: H.H. de Iongh, O.S. Bánki, W. Bergmans and M.J. van der Werff ten Bosch Lay out: Sjoukje Rienks Cover design: Sjoukje Rienks Front cover photograph: Common crane (Grus grus): F. -

The Contribution to Wildlife Conservation of an Italian Recovery

Nature Conservation 44: 1–20 (2021) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.44.65528 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://natureconservation.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation The contribution to wildlife conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre Gabriele Dessalvi1, Enrico Borgo2, Loris Galli1 1 Department of Earth, Environmental and Life Sciences (DISTAV), Genoa University, Corso Europa 26, 16132, Genoa, Italy 2 Museum of Natural History “Giacomo Doria”, Via Brigata Liguria, 9, 16121, Genoa, Italy Corresponding author: Loris Galli ([email protected]) Academic editor: Christoph Knogge | Received 5 March 2021 | Accepted 20 April 2021 | Published 10 May 2021 http://zoobank.org/F5D4BBF2-A839-4435-A1BA-83EAF4BA94A9 Citation: Dessalvi G, Borgo E, Galli L (2021) The contribution to wildlife conservation of an Italian Recovery Centre. Nature Conservation 44: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.44.65528 Abstract Wildlife recovery centres are widespread worldwide and their goal is the rehabilitation of wildlife and the subsequent release of healthy animals to appropriate habitats in the wild. The activity of the Genoese Wild- life Recovery Centre (CRAS) from 2015 to 2020 was analysed to assess its contribution to the conservation of biodiversity and to determine the main factors affecting the survival rate of the most abundant species. In particular, the analyses focused upon the cause, provenance and species of hospitalised animals, the sea- sonal distribution of recoveries and the outcomes of hospitalisation in the different species. In addition, an in-depth analysis of the anthropogenic causes was conducted, with a particular focus on attempts of preda- tion by domestic animals, especially cats. -

Improving the Conservation Status of Migratory Landbirds in the African-Eurasian Region

CMS Distr: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/Resolution 10.27 MIGRATORY SPECIES Original: English IMPROVING THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF MIGRATORY LANDBIRDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION Adopted by the Conference of the Parties at its Tenth Meeting (Bergen, 20-25 November 2011) Concerned at the rapid decline in many African-Eurasian migratory landbird species; Recognizing that Article II of the Convention requires all Parties to endeavour to conclude Agreements covering the conservation and management of migratory species listed in Appendix II of the Convention; Noting that CMS Article IV encourages Parties to conclude Agreements regarding populations of migratory species; Aware that five African-Eurasian migratory landbirds are listed on Appendix I of CMS, four of which are among 85 African-Eurasian migratory landbirds listed on Appendix II; Further aware that the species listed in Appendix I and Appendix II include more than 13 of the common trans-Saharan migrants known to have suffered the most severe population declines, such as several species of warblers, Sylviidae, the European Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca, the Spotted Flycatcher Muscicapa striata, the Northern Wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe, the Whinchat Saxicola rubetra, the Common Nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos, the European Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur turtur and the European Bee- eater Merops apiaster; Further recognizing that the five African-Eurasian landbird species listed on CMS Appendix I are all categorized as either Endangered or Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List 2010 (the Basra Reed-warbler Acrocephalus griseldis, the Spotted Ground-thrush Zoothera guttata, the Syrian Serin Serinus syriacus, the Blue Swallow Hirundo atrocaerulea and the Aquatic Warbler Acrocephalus paludicola) and that two Near Threatened species (the European Roller Coracias garrulus and the Semi-collared Flycatcher Ficedula semitorquata) are listed on Appendix II. -

Field-Identification of Hippolais Warblers by D.I M

Field-identification of Hippolais warblers By D.I M. Wallace INTRODUCTION THE GENUS HIPPOLAIS is a small one of only six species. Two of these, the Icterine Warbler H. icterina and the Melodious Warbler H. polyglotta, are now proven annual vagrants to Great Britain and Ireland; another two, the Olivaceous Warbler H.pallida and the Booted Warbler H. caligata, occur here as rare stragglers; and the final pair, the Olive-tree Warbler H. olivetorum and Upcher's Warbler H. languida, might conceivably reach us in the future. All except the last breed in Europe, though the Booted Warbler does so no further west than Russia. For many years the members of this genus have been labelled difficult to identify, in much the same way as other groups where plumage pattern alone is not always sufficient for certain diagnosis. Williamson (i960) included all the species and races in the first of his systematic guides to the warblers, but the detailed information he gave was primarily intended to aid ringers with birds in the hand and, although some general comments on the genus (at times dangerously misleading if applied to individual species) were made by Alexander (1955), no descriptive treatment so far published is adequate for accuracy in field identification. I do not presume to be able to meet this need fully, but I have watched all six species on migration in Europe or the Near East (Jordan) and have more thoroughly studied three of them in both their European breeding-habitats and their African winter-quarters. In addition, I have discussed Hippolais identification with many field ornithologists and have investigated all the records published in this journal and several observatory reports over the last ten years.