PB 80–04–2 December 2004 Vol. 17, No. 2 from the Commandant Special Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Bolton 7 Wood, Donald Tedford, Henty On

• ,K,-. ip PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 28, 19B7 11 Average Dally Net Press Run The Weather illanrh^Hl^r lEirpttfnn ii^ralb T For the Week Ended PWMSrt H D.-B. W estker July' *7, 1987 James R. Carrara, son of Mr. and Mrs. James V. Carrara, 44 MUden letemltteat^Usfit rets to- About Town Prospect St. a student at the Uni 12.002 night. Lo^r 88-M. Friday mild, feW' versity of Utah, la one of 700 ehowera meatl.v Is feremood* High , "MUieheatcr Orange, No. 81. haa Member ht the Andit Naval Reserve midshipmen who IV ■«»»• .v’ Bnrean at Oreolstion In 70s. N t the date of Wedneartav. Sept. received three weeks Indoctrina 4. for a mj-atery ride. The group tion this month under the AUan Manche$ter^A City of Village Charm ................................... .......... will leave from Orange Hall at tic Amphibious Training Com 7 pjn. AirCrengcra who plan mand. V • DOUBLE GREEN to attend ahouU contact Mra. ZM VOL. LX X V I, NO. 281 (TWENTY PAGES) M a n c h e s t e r , c o n n ., T h u r s d a y , a u g u s t 29.1957 (Ciasslfled Advertising on Fage IS) PRICE FIVE CENTS Olive Murphy, 34 Weat St., or Mra. Haael Anderaon, 1S3 High S t ------ ------- ^------------------------ 1 : : , ^ I Two^ Here. Picked Membera of Rockville Emblem Club, No. 4, will meet at 7:30 this For Chapter Posts r STAMPS WITH ALL CASH Conferees evening at the Burke Funeral ------- 0 Rome, 76 Prospect St., Rockville, TV'o local nicn have been elected / jon Airs to pay their respects to former officers of the Hartford Society for mayor Raymond E. -

The Use of Trained Elephants for Emergency Logistics, Off-Road Conveyance, and Political Revolt in South and Southeast Asia

When Roads Cannot Be Used The Use of Trained Elephants for Emergency Logistics, Off-Road Conveyance, and Political Revolt in South and Southeast Asia Jacob Shell, Temple University Abstract Th is article is about the use of trained Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) for transportation, in particular across muddy or fl ooded terrain, clandestine off - road transportation, and during guerrilla operations or political revolts. In a sense, these are all in fact the same transport task: the terrestrial conveyance of people and supplies when, due to weather or politics or both, roads cannot be used. While much recent work from fi elds such as anthropology, geography, history, and conservation biology discusses the unique relationship between humans and trained elephants, the unique human mobilities opened up by elephant-based transportation has been for the most part overlooked as a re- search topic. Looking at both historical and recent (post–World War II) exam- ples of elephant-based transportation throughout South and Southeast Asia, I suggest here that this mode of transportation has been especially associated with epistemologically less visible processes occurring outside of state-recog- nized, formal institutions. Keywords 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Asian elephants, Kachin confl ict, mahouts, Sepoy Mutiny, smuggling, upland Southeast Asia Introduction Since World War II, transportation by way of trained Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) has been the only mode of transport with which the world’s wealth- iest countries have had virtually no local experience.1 My aim, in this article, is to approach this much overlooked, and imperiled, method of conveyance by focusing on those transport tasks for which—so recent human experience Transfers 5(2), Summer 2015: 62–80 ISSN 2045-4813 (Print) doi: 10.3167/TRANS.2015.050205 ISSN 2045-4821 (Online) When Roads Cannot Be Used suggests—the mode seems to be intrinsically and uniquely useful. -

Endorsers | US Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott Of

http://www.usacbi.org/endorsers/ Organizing Collective FAQs What You Can Do Our Activities Boycott News Donate search search Endorsers USACBI Endorsements from Colleagues at American Institutions: HELP SUPPORT USACBI! Your donation to USACBI Mission Statement Note: institutional names are for identification purposes only. allows us to print materials, publish information, and build Endorse Our Call to Boycott 1. Elizabeth Aaronsohn, Central Connecticut State University support among academics and cultural workers for the 2. Elmaz Abinader, Mills College* boycott of Israel. Click the Endorsers 3. Rabab Abdulhadi, San Francisco State University*** button below to donate! 4. Suad Abdulkhabeer, Purdue University Reports and Resources 5. Mohammed Abed, California State University, Los Angeles 6. Thomas Abowd, Colby College RECENT BDS NEWS FAQs 7. Khaled Abou El Fadl, University of California, Los Angeles, Law School Boycott Israel 8. Feras Abou-Galala, University of California, Riverside*** Guidelines for Applying the Movement Erupts in International Academic Boycott of 9. Matthew Abraham, DePaul University the US Academy: A Israel 10. Wahiba Abu-Ras, Adelphi University Statement on the ASA vote to endorse the academic 11. Georgia Acevedo, University of Hawaii at Manoa boycott of Israeli Universities Take Action 12. Deanna Adams, Syracuse University USACBI congratulates the American 13. Fawzia Afzal-Khan, Montclair State University Studies Association (ASA) for its USACBI Speakers Bureau 14. Kritika Agarwal, SUNY Buffalo unprecedented vote endorsing the 15. Tahereh Aghdasifar, Emory University Palestinian call for an academic Academic Boycott Resolutions 16. Roberta Ahlquist, San Jose State University boycott of Israeli universities.... Stop Technion/Cornell 17. Patty Ahn, University of Southern California Collaboration! 18. -

Energy Insights Back-To-School Virtual Energy Seminar Finale RBC Capital Markets Hosted the Finale of Its Back-To-School Energy Seminar Yesterday

RBC Global Equity Team Click here for contributing analysts' contact information September 3, 2020 Energy Insights Back-to-School Virtual Energy Seminar Finale RBC Capital Markets hosted the finale of its Back-to-School Energy Seminar yesterday. The event consisted of a number of panel discussions and fireside chats. Discussions were lively and touched on a broad array of topics, the highlights of which are summarized below, with more detail included within this report. The summary from Day 1 can be found here. EQUITY RESEARCH Thematic Highlights Framing the Global Oil Landscape. Renewables would be the clear winner if Joe Biden is elected in November, though natural gas could receive significant under-the-radar support, as its development assists key climate and foreign policy objectives. Perhaps most consequential for near-term balances if Biden is elected would be an American re-entry into the 2015 JCPOA nuclear deal that could bring 1 mb/d+ of Iranian exports back onto the market by 2H 2021. Gulf producers contend that they are well positioned for the looming energy transition, as they have the lowest-cost and greenest barrels. LNG Insights and Perspective. We hosted a conversation with Shell’s Director of Integrated Gas & New Energies, Maarten Wetselaar, which ran through some key takeaways on the current status of the LNG market and longer-term dynamics. We found Shell more bullish on LNG than in our recent conversations, particularly around medium-term gas pricing (2023+). Renewable and Alternative Energy Panel. Algonquin and NextEra emphasized the increasing role of ESG in conversations, from investor dialogue to financing discussions. -

Toungoo Dynasty: the Second Burmese Empire (1486 –1752)

BURMA in Perspective TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: GEOGRAPHY......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Geographic Divisions .............................................................................................................. 1 Western Mountains ........................................................................................................... 2 Northern Mountains .......................................................................................................... 2 Shan Plateau ..................................................................................................................... 3 Central Basin and Lowlands ............................................................................................. 3 Coastal Strip ..................................................................................................................... 4 Climate ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bodies of Water ....................................................................................................................... 5 Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) River ........................................................................................ 6 Sittang River .................................................................................................................... -

Journal of the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association Table of Contents

Journal of the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association Table of Contents VOLUME 88 WINTER 2020 NUMBER 1 Preface Gov. John Bel Edwards............................................................ 3 Foreword Kyle R. “Chip” Kline Jr. and Lawrence B. Haase................... 4 Introduction Syed M. Khalil and Gregory M. Grandy............................... 5 A short history of funding and accomplishments post-Deepwater Horizon Jessica R. Henkel and Alyssa Dausman ................................ 11 Coordination of long-term data management in the Gulf of Mexico: Lessons learned and recommendations from two years of cross-agency collaboration Kathryn Sweet Keating, Melissa Gloekler, Nancy Kinner, Sharon Mesick, Michael Peccini, Benjamin Shorr, Lauren Showalter, and Jessica Henkel................................... 17 Gulf-wide data synthesis for restoration planning: Utility and limitations Leland C. Moss, Tim J.B. Carruthers, Harris Bienn, Adrian Mcinnis, Alyssa M. Dausman .................................. 23 Ecological benefits of the Bahia Grande Coastal Corridor and the Clear Creek Riparian Corridor acquisitions in Texas Sheri Land ............................................................................... 34 Ecosystem restoration in Louisiana — a decade after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill Syed M. Khalil, Gregory M. Grandy, and Richard C. Raynie ........................................................... 38 Event and decadal-scale modeling of barrier island restoration designs for decision support Joseph Long, P. Soupy -

Deciphering the Landscape of International Humanitarian Law In

International Review of the Red Cross (2019), 101 (911), 737–770. Children and war doi:10.1017/S1816383120000107 Deciphering the landscape of international humanitarian law in the Asia-Pacific Suzannah Linton* Suzannah Linton is an Adjunct Professor at the School of International Law, China University of Political Science and Law, and a member of the Expert Committee of the International Academy of the Red Cross and Red Crescent at Suzhou University. Abstract The 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Geneva Conventions on 12 August 1949 provided an opportunity for reflection on international humanitarian law (IHL). This article continues that reflection and presents some fresh scholarship about and from the Asia-Pacific region. The region’s plurality leads to a complex and diverse landscape where there is no single “Asia-Pacific perspective on IHL” but there are instead many approaches and trajectories. This fragmented reality is, however, not a mess of incoherence and contradiction. In the following pages, the author argues for and justifies the following assessments. The first is that the norm of humanity in armed conflict, which underpins IHL, has deep roots in the region. This, to some extent, explains why there is no conceptual resistance to IHL, in the way that exists with the human rights doctrine. The second is that there has been meaningful participation of certain States from the region in IHL law-making. Thirdly, some Asia-Pacific States are among those actively contributing to the development of new or emerging areas relevant to IHL, such as outer space, cyberspace and the protection of the environment in armed conflict. -

Corpus Christi College the Pelican Record

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LIII December 2017 CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE THE PELICAN RECORD Vol. LIII December 2017 i The Pelican Record Editor: Mark Whittow Acting Editor: Neil McLynn Assistant Editors: Sara Watson, David Wilson Design and Printing: Mayfield Press Published by Corpus Christi College, Oxford 2017 Website: http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk Email: [email protected] Front cover: Detail from the Oglethorpe Bible, bequeathed to Corpus Christi by James Oglethorpe (d. 1785), founder of the American colony of Georgia. Back cover: Corpus Christi College from an original oil painting by Ceri Allen, featured in the 2017 edition of the Oxford Almanack. ii The Pelican Record CONTENTS President’s Report .................................................................................. 3 Dr. Mark Whittow – A Tribute Neil McLynn ............................................................................................. 7 Rededication of the College Chapel Judith Maltby ............................................................................................ 14 Foundation Dinner 2017 Keith Thomas ............................................................................................ 18 Creating the Corpus Christi Quincentenary Salt Angela Cork .............................................................................................. 26 A Year of Celebration: Corpus Turns 500 Sarah Salter ............................................................................................... 29 Review: As You Like It -

1981 Journal

OCTOBER TERM, 1981 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics n General in Appeals in Arguments in Attorneys iv Briefs iv Certiorari v Costs vi Judgments, Mandates and Opinions vi Miscellaneous vni Original Cases vni Parties x Records x Rehearings xi Rules xi Stays and Bail xi Conclusion xi (i) II STATISTICS AS OF JULY 2, 1982 In Forma Paid Original Pauperis Total Cases Cases Number of cases on docket 22 2,935 2,354 5,311 Cases disposed of 6 2,390 2,037 4,433 Remaining on docket 16 545 317 878 Cases docketed during term: Paid cases 2,413 In forma pauperis cases 2,004 Original cases , 5 Total 4,422 Cases remaining from last term 889 Total cases on docket 5,311 Cases disposed of 4,433 Number remaining on docket 878 Petitions for certiorari granted: In paid cases 152 In in forma pauperis cases 7 Appeals granted: In paid cases 51 In in forma pauperis cases 0 Total cases granted plenary review 210 Cases argued during term 184 Number disposed of by full opinions *170 Number disposed of by per curiam opinions **10 Number set for reargument next term 4 Cases available for argument at beginning of term 102 Disposed of summarily after review was granted 8 Original cases set for argument 2 Cases reviewed and decided without oral argument 126 Total cases available for argument at start of next term ***126 Number of written opinions of the Court 141 Opinions per curiam in argued cases **9 Number of lawyers admitted to practice as of October 3, 1982: On written motion 4,077 On oral motion 1,002 Total 5,079 * Includes No. -

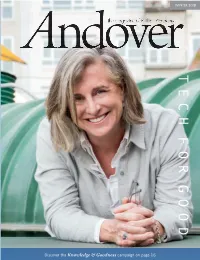

T E C H F O R G O

WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER 2 018 -

Burma and Superpower Rivalries in the Asia-Pacific Andrew Selth

Naval War College Review Volume 55 Article 4 Number 2 Spring 2002 Burma and Superpower Rivalries in the Asia-Pacific Andrew Selth Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Selth, Andrew (2002) "Burma and Superpower Rivalries in the Asia-Pacific," Naval War College Review: Vol. 55 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol55/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Selth: Burma and Superpower Rivalries in the Asia-Pacific Andrew Selth is a visiting fellow at the Australian National University’s Strategic and Defence Studies Center. He has published widely on strategic and Asian affairs, including Transforming the Tatmadaw: The Burmese Armed Forces since 1988 (Canberra, 1996) and Burma’s Secret Military Partners (Canberra, 2000). He has just completed a comprehensive study entitled Burma’s Armed Forces: Power without Glory, which is due to be published in the United States later this year. This article is drawn from Burma: A Strategic Perspec- tive, Asia Foundation Working Paper 13 (San Fran- cisco, 2001). A shorter version was presented at the conference on “Strategic Rivalries on the Bay of Bengal: The Burma/Myanmar Nexus,” held in Washington, D.C., on 1 February 2001 and sponsored by the Asian Studies Center and Center for Peace and Security Studies, Georgetown University; the Center for Strategic Studies of the CNA Corporation; the Asia Foundation; and the Sasakawa Peace Foundation. -

The Rochester Sentinel

1 The Rochester Sentinel 2012 Monday, January 2, 2012 No Paper – Holiday Tuesday, January 3, 2012 Lynda Bennett Lynda BENNETT, 51, 17607 Kenilworth Road, Argos, died at 5:58 p.m. Sunday at Indiana University Health Goshen Hospital. Arrangements are pending with the Earl-Grossman Funeral Home, Argos. Annamae T. Carnett Annamae T. CARNETT, 90, Winamac, died at 9:42 a.m. Friday at Pulaski Memorial Hospital, Winamac. Survivors include four sons, Clyde Carnett, of Highland, Donald Dooley, San Angelo, Texas, Dick Carnett, of Hammond, and Joe Carnett, of Hiram, Ga.; and three daughters, Carla Clark, of Pasedena, Fla., Linda Hotuyec, of Joliet, Ill., and Marty Acosta, of Joliet, Ill. Services are at 10:30 a.m. EST, 11:30 a.m. CST Wednesday at the Odom Funeral Home, Culver, with visitation from 9-10:30 a.m. EST, 10-11:30 a.m. CST at the funeral home. Mary Ellen Davis Mary Ellen DAVIS, 88, 635 Oakhill Ave., Plymouth, died at 11 a.m. Saturday at Miller's Merry Manor, Plymouth. Survivors include one daughter, Sherry Hite, of Oakland, Calif.; three sons, John Hite, of Hurst, Texas, Rick Hite, of Plymouth, and Carl Hite, of North Carolina; one brother, Jim Workman, of Kokomo; and one sister, Ann Baker, of Osceola. 2 Services are at 10 a.m. Wednesday at the First Baptist Church, Argos, with visitation from 4-8 p.m. today at the Earl-Grossman Funeral Home, Argos. Wednesday, January 4, 2012 Derek Jan Anglin Sept. 23, 1958-Jan. 3, 2012 Derek Jan ANGLIN, of 7009 W. Crystal Lake Road, Warsaw, passed away at 6:12 a.m.