Dvoretsky Lessons 89

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grandmaster Opening Preparation Jaan Ehlvest

Grandmaster Opening Preparation By Jaan Ehlvest Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Preface This book is about my thoughts concerning opening preparation. It is not a strict manual; instead it follows my personal experience on the subject of openings. There are many opening theory manuals available in the market with deep computer analysis – but the human part of the process is missing. This book aims to fill this gap. I tried to present the material which influenced me the most in my chess career. This is why a large chapter on the Isolated Queen’s Pawn is present. These types of opening positions boosted my chess understanding and helped me advance to the top. My method of explaining the evolution in thinking about the IQP is to trace the history of games with the Tarrasch Defence, from Siegbert Tarrasch himself to Garry Kasparov. The recommended theory moves may have changed in the 21st century, but there are many positional ideas that can best be understood by studying “ancient” games. Some readers may find this book answers their questions about which openings to play, how to properly use computer evaluations, and so on. However, the aim of this book is not to give readymade answers – I will not ask you to memorize that on move 23 of a certain line you must play ¤d5. In chess, the ability to analyse and arrive at the right conclusions yourself is the most valuable skill. I hope that every chess player and coach who reads this book will develop his or her understanding of opening preparation. -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937, 1927, 552 Pages, Alexander Alekhine, 0486249417, 9780486249414, Dover Publications, 1927

My Best Games of Chess, 1908-1937, 1927, 552 pages, Alexander Alekhine, 0486249417, 9780486249414, Dover Publications, 1927 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1OiqRxa http://goo.gl/RTzNX http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=My+Best+Games+of+Chess%2C+1908-1937 One of chess's great inventive geniuses presents his 220 best games, with fascinating personal accounts of the dazzling victories that made him a legend. Includes historic matches against Capablanca, Euwe, and Bogoljubov. Alekhine's penetrating commentary on strategy, tactics, and more — and a revealing memoir. Numerous diagrams. DOWNLOAD http://t.co/6HPUQSukXD http://ebookbrowsee.net/bv/My-Best-Games-of-Chess-1908-1937 http://bit.ly/1haFYcA Games played in the world's Championship match between Alexander Alekhin (holder of the title) and E. D. Bogoljubow (challenger) , Frederick Dewhurst Yates, Alexander Alekhine, Efim Dmitrievich Bogoljubow, W. Winter, 1930, World Chess Championship, 48 pages. Championship chess , Philip Walsingham Sergeant, Jan 1, 1963, Games, 257 pages. Alexander Alekhine's Best Games , Alexander Alekhine, Conel Hugh O'Donel Alexander, John Nunn, 1996, Games, 302 pages. This guide features Alekhine's annotations of his own games. It examines games that span his career from his early encounters with Lasker, Tarrasch and Rubenstein, through his. From My Games, 1920-1937 , Max Euwe, 1939, Chess, 232 pages. Masters of the chess board , Richard Réti, 1958, Games, 211 pages. The book of the Nottingham International Chess Tournament 10th to 28th August, 1936. Containing all the games in the Master's Tournament and a small selection of games from the Minor Tournament with annotations and analysis by Dr. -

Ultimate Tarrasch Sample

The Ultimate Tarrasch Defense by Eric Schiller Published by Sid Pickard & Son, Dallas All text copyright 2001 by Eric Schiller. Portions of the text materials and chess analysis are taken from Complete Defense to Queen Pawn Openings by Eric Schiller, Published by Cardoza Publishing. Additional material is adapted from Play the Tarrasch by Leonid Shamkovich and Eric Schiller, published by Pergamon Press in 1984. Some game annotations have previously appeared in various books and publications by Eric Schiller. This document is distributed as part of The Ultimate Tarrasch CD-Rom, published by Pickard & Son, Publishers (www.ChessCentral.com). Additional analysis on the Tarrasch Defense can be found at http://www.chesscity.com/. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................2 What is the Tarrasch Defense ..................................................................................................................................................2 Who plays the Tarrasch Defense .............................................................................................................................................3 How to study the Tarrasch Defense.........................................................................................................................................3 Dr. Tarrasch and his Defence ......................................................................................................................................................4 -

A Conversation with a Ten Year Old Author

YOUNG GUNS Oliver Boydell came up with a simple plan: language because my goal was to teach the 1. Pick exciting games from the past important chess concepts 2. Make the notes breezy and brief and this is best done when 3. Use lots of diagrams the language is clear and 4. Have questions for the reader with answers everyone – kids and adults – in the back of the book can understand. 5. Have a “lesson” or two, a concept, to take with them that they should remember How do you go through a about playing good chess game? Do you take notes? 6. Give a favorite move – one that might Do you use a chess engine stick with the reader. as you go? I take notes on what I think For the miserable types that give a is interesting. I might go disapproving “harumph” to all this, you’ve over it several times to By Pete Tamburro forgotten what it is to be a kid. make sure I didn’t make any mistakes, like missing an Our chat was fun and we share it here. obvious tactic. I would use the engine several times, even different engines, to make sure I agreed with ack in 2010, I was assigned to How does it feel to be an the evaluation. I also look write a review of a 14-year- author? for certain ideas I can write old boy’s first chess book, I’m proud of myself and am about, like doubling rooks Mastering Positional Chess. really excited. I had never attacking games. -

World Chess Hall of Fame Brochure

ABOUT US THE HALL OF FAME The World Chess Hall of Fame Additionally, the World Chess Hall The World Chess Hall of Fame is home to both the World and U.S. Halls of Fame. (WCHOF) is a nonprofit, collecting of Fame offers interpretive programs Located on the third floor of the WCHOF, the Hall of Fame honors World and institution situated in the heart of that provide unique and exciting U.S. inductees with a plaque listing their contributions to the game of chess and Saint Louis. The WCHOF is the only ways to experience art, history, science, features rotating exhibitions from the permanent collection. The collection, institution of its kind and offers a and sport through chess. Since its including the Paul Morphy silver set, an early prototype of the Chess Challenger, variety of programming to explore inception, chess has challenged artists and Bobby Fischer memorabilia, is dedicated to the history of chess and the the dynamic relationship between and craftsmen to interpret the game accomplishments of the Hall of Fame inductees. As of May 2013, there are 19 art and chess, including educational through a variety of mediums resulting members of the World Hall of Fame and 52 members of the U.S. Hall of Fame. outreach initiatives that provide in chess sets of exceptional artistic context and meaning to the game skill and creativity. The WCHOF seeks and its continued cultural impact. to present the work of these craftsmen WORLD HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES and artists while educating visitors 2013 2008 2003 2001 Saint Louis has quickly become about the game itself. -

Carl August Walbrodt

Вальбродт, Карл Август Карл Август Вальбродт Carl August Walbrodt приблизительно в 1895—1902 годах Страны: Германия Дата 28 ноября 1871 рождения: Место Амстердам рождения: Дата смерти: 3 октября 1902 (30 лет) Место смерти: Берлин Карл Август Вальбродт (нем. Carl August Walbrodt; 28 ноября 1871,Амстердам — 3 октября 1902, Берлин) — немецкий шахматист. Разделил 1-2-е место с К. Барделебеном на национальном турнире вКиле (1893). Участник международных турниров: Дрезден (1892) иЛейпциг (1894, турниры Германского шахматного союза) — 4-5- е;Гастингс (1895) — 11-е; Нюрнберг (1896) — 7-8-е; Будапешт (1896) — 6- 7-е; Берлин (1897) — 2-е места. Выиграл матчи у Э. Шаллопа (1891) — 5½ : 3½ (+5 −3 =1), К. Барделебена (1892) — 7 : 2 (+5 −0 =4) и В. Кона (1894) — 5 : 0; в 1894 закончил матч с Ж. Мизесом — 6½ : 6½ (+5 −5 =3). Литература Шахматы : энциклопедический словарь / гл. ред. А. Е. Карпов. — М.:Советская энциклопедия, 1990. — С. 53. — 624 с. — 100 000 экз. — ISBN 5-85270-005-3. Ссылки Партии Карла Вальбродта в базе Chessgames Личная карточка Карла Вальбродта на сайте 365chess.com Karl August Walbrodt Number of games in database: 183 Years covered: 1891 to 1900 Overall record: +65 -59 =56 (51.7%)* * Overall winning percentage = (wins+draws/2) / total games Based on games in the database; may be incomplete. 3 exhibition games, odds games, etc. are excluded from this statistic. MOST PLAYED OPENINGS With the White pieces: With the Black pieces: Ruy Lopez (34) Ruy Lopez (17) C77 C67 C80 C65 C83 C77 C65 C67 C72 C62 French Defense (13) French Defense -

José Raúl Capablanca Y Graupera 3Rd Classical World Champ from 1921-1927

José Raúl Capablanca y Graupera 3rd classical world champ from 1921-1927 José Raúl Capablanca, y Graupera (19 November 1888 – 8 March 1942) nicknamed “The Human Chess Machine, was a Cuban chess player who was world chess champion from 1921 to 1927. A chess prodigy, he is considered by many as one of the greatest players of all time, widely renowned for his exceptional endgame skill and speed of play. His skill in rapid chess lent itself to simultaneous exhibitions. José Raúl Capablanca, the second surviving son of a Spanish army officer,[3] was born in Havana on November 19, 1888.[4] According to Capablanca, he learned to play chess at the age of four by watching his father play with friends, pointed out an illegal move by his father, and then beat his father.[5] Between November and December 1901, he beat Cuban champion Juan Corzo in a match on 17 November 1901, two days before his 13th birthday.[1][2] However, in April 1902 he came in fourth out of six in the National Championship, losing both his games with Corzo.[7] In 1905 Capablanca joined the Manhattan Chess Club, and was soon recognized as the club's strongest player.[4] He was particularly dominant in rapid chess, winning a tournament ahead of the reigning World Chess Champion, Emanuel Lasker, in 1906.[4] He represented Columbia on top board in intercollegiate team chess.[8] In 1908 he left the university to concentrate on chess.[4][6] His victory over Frank Marshall in a 1909 match earned him an invitation to the 1911 San Sebastian tournament, which he won ahead of players such as Akiba Rubinstein, Aron Nimzowitsch and Siegbert Tarrasch. -

The Fidelity Chessmaster 2100

_~HE FIDELIT'0~ HESS ASTE Table of Contents 1. Let's Play Chess ........... ................ 3 (Provided by the U.S. Chess Federation. It's your official Introduction to the play of the game. If you already know how to play chess. you may wan t to skip this section.) 2 . A History of Chess ......................... 9 (Everyth ing you ever wanted to know. a nd more, about how the game came to be.) 3. World Champions and Their Play.... 12 (The inside story about the greatest "Wood Pushers' in the world - and the nuttiest.) 4 . Chess and Machines ..................... 28 (Trace your chess-playin g computer's antecedents back to Maelzel' s Turk, a famous trick Inven ted in 1763.) 5 . Library of Classic Games ............... 33 (Here's a fascinating collection of 11 0 hard fo ught games as played by the greatest masters in h istory. The Ch essmaster 2 100 will replay th em for you on comman d.) 6 . Bralnteasers ................................ 51 (Some instructive problems th at may teach you a few sneaky tricks.) 7 . Algebraic Notation ....................... 53 (e4. Nxf3 ... what's it all about? Chess shorthand explained.) Copyright © 1988 The Software Toolworks. Printed In U.S.A. by Priority Software All Righ ts Reserved. Packaging. Santa Ana, California. 3 Let's Play Chess The Pieces Chess is a game for two players. one with White always moves first. and then the the "White" pieces and one with the players take turns movlng. Only one "Black" - no matter what colors your set piece may be moved at each turn (except actually uses. -

The Lasker Method to Improve in Chess

Gerard Welling and Steve Giddins The Lasker Method to Improve in Chess A Manual for Modern-Day Club Players New In Chess 2021 Contents Explanation of symbols...........................................6 Introduction....................................................7 Chapter 1 General chess philosophy and common sense.........11 Chapter 2 Chess strategy and the principles of positional play....14 Chapter 3 Endgame play .....................................19 Chapter 4 Attack ............................................36 Chapter 5 Defence...........................................58 Chapter 6 Knights versus bishops .............................71 Chapter 7 Amorphous positions ..............................75 Chapter 8 An approach to the openings....................... 90 Chapter 9 Games for study and analysis.......................128 Chapter 11 Combinations and tactics ..........................199 Chapter 12 Solutions.........................................215 Index of openings .............................................233 Index of names ............................................... 234 Bibliography ..................................................238 5 Introduction The game of chess is in a constant state of flux, and already has been for a long time. Several books have been written about the advances made in chess, about Wilhelm Steinitz, who is traditionally regarded as having laid the foundation of positional play (although Willy Hendriks expresses his doubts about this in his latest revolutionary book On the Origin of good -

Common Sense in Chess, Emanuel Lasker, Courier Dover Publications, 1965, 1965, 0486214400, 9780486214405, 139 Pages

Common Sense in Chess, Emanuel Lasker, Courier Dover Publications, 1965, 1965, 0486214400, 9780486214405, 139 pages DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1WZ61vS http://goo.gl/RyLmu http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=Common+Sense+in+Chess From the day when he won the World's Chess Championship from Steinitz in 1894 to his defeat by Capablanca in 1921, Emanuel Lasker reigned as the undisputed chess genius of the world. Though surely his unique talent cannot be transmitted, the basic principles upon which his chess mastery was based are outlined clearly and succinctly for the benefit of all chess enthusiasts in his "Common Sense in Chess." DOWNLOAD http://tiny.cc/TAzcUm http://bit.ly/1tgiCdo Meet the Masters - The Modern Chess Champions and Their Most Characteristic Games - With Annotations and Biographies , Max Euwe, 2010, Games, 302 pages. Further steps in chess , Owen Hindle, 1970, Games, 116 pages. Colle's Chess Masterpieces , Fred Reinfeld, 1936, Chess, 92 pages. Chess , Robert Frederick Green, 1973, Chess, 113 pages. The Art of Chess Combination A Guide for All Players of the Game, Eugene Znosko-Borovsky, EvgeniД Aleksandrovich Znosko-BorovskiД, 1959, Games, 212 pages. A short history of the ballet and a review of Balanchine's own career as ballet master and choreographer accompany the stories of more than four hundred ballets. Lasker's Chess Magazine, Volume 2 , Emanuel Lasker, 1905, Chess, . Four Famous Chess Matches Janowsky V. Marshall, Both Match and Return Match, Lasker V. Tarrasch and Lasker V. Schlechter, David Janowski, Frank James Marshall, Emanuel Lasker, Siegbert Tarrasch, C. Schlechter, 1908, Chess, 124 pages. -

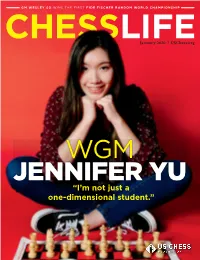

“I'm Not Just a One-Dimensional Student.”

GM WESLEY SO WINS THE FIRST FIDE FISCHER RANDOM WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP January 2020 | USChess.org WGM JENNIFER YU “I’m not just a one-dimensional student.” The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com The Agile London System Kaufman’s New Repertoire for Black and White A Solid but Dynamic Chess Opening Choice for White A Complete, Sound and User-friendly Chess Opening Repertoire Alfonso Romero & Oscar de Prado 336 pages - $29.95 Larry Kaufman 464 pages - $32.95 The secrets behind sharp ideas such as the Barry Attack, the A lucidly explained, ready-to-go and easy-to-digest Jobava Attack and the hyper-aggressive Pereyra Attack. repertoire with sound, practi cal lines that do not go out of “With plenty of fresh material that should ensure that it will date rapidly. Suitable for masters while perfectly accessible be the reference work on the complete London System for for amateurs. You always get two opti ons and don’t have to play the sharpest lines. As this is the fi rst opening book years to come.” – GM Glenn Flear NEW! “Encyclopedic in scope.” – John Hartmann, ChessLife that is primarily based on Monte Carlo Search, it’s a real goldmine of improvements on existi ng theory. Winning in the Chess Opening The Hippopotamus Defence 700 Ways to Ambush Your Opponent A Deceptively Dangerous Universal Chess Opening System for Black Nikolay Kalinichenko 464 pages - $24.95 Alessio De Santi s 320 pages - $32.95 “Practi ce tacti cs while learning about various openings “Litt le short of a revelati on.