Conservation Assessment for Yellowwood (Cladrastis Kentukea (Dum.-Cours.) Rudd)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going Clonal: Beyond Seed Collecting

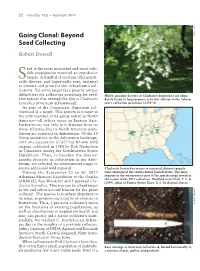

22 Arnoldia 75/3 • February 2018 Going Clonal: Beyond KYLE PORT Seed Collecting Robert Dowell eed is the most important and most valu- able propagation material an expedition Stargets. A handful of seed can offer geneti- cally diverse, and logistically easy, material to procure and grow for the Arboretum’s col- lections. Yet some target taxa present unique difficulties for collectors searching for seed. White, pea-like flowers of Cladrastis kentuckea are abun- One species that exemplifies this is Cladrastis dantly borne in long racemes, as in this old tree in the Arbore- kentukea (American yellowwood). tum’s collection (accession 16370*A). As part of the Campaign, American yel- lowwood is a target. This species is unique as the only member of its genus native to North America—all others occur in Eastern Asia. Furthermore, not only is it disjunct from its Asian relatives, but its North American popu- lations are scattered in distribution. Of the 13 living accessions in the Arboretum landscape, only one (accession 51-87) has known wild origins, collected in 1986 by Rob Nicholson in Tennessee during the Southeastern States Expedition. Thus, to broaden the species’ genetic diversity in cultivation in the Arbo- retum, we selected its westernmost range to source additional wild material. Cladrastis kentuckea occurs in scattered, disjunct popula- During the September 22 to 30, 2017 tions throughout the south-central United States. The large Arkansas-Missouri Expedition to the Ozarks expanse in the westernmost part of the species range served as the source of the 2017 collection. Modified from Little, E. L. Jr. -

Guidance Document for Tree Conservation, Landscape, and Buffer Requirements Article III Section 3.2

Guidance Document For Tree Conservation, Landscape, and Buffer Requirements Article III Section 3.2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Revision History ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Technical Standards ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Tree Measurements .......................................................................................................................... 2 2. Specimen Trees ................................................................................................................................. 4 3. Boundary Tree ................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Tree Density Calculation ................................................................................................................... 5 Tree Removal Requirements ...................................................................................................................... 11 Tree Care ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 1. Planting ........................................................................................................................................... 12 2. Mulching ........................................................................................................................................ -

Denumire Științifică: Cladrastis Kentukea

Denumire științifică: Ordin: Fabales Cladrastis kentukea (Dum.Cours.) Rudd Denumire populară: Arborele cu lemn galben Familie: Fabacae Descriere: Este un arbore de mărime mică-medie, cu o coroană rotundă şi largă şi cu scoarţă (ritidom) netedă şi gri. Frunzele sunt compus penate, cu 5-11 foliole alterne, cu marginea întreagă şi fiecare cu un vârf ascuţit. Toamna frunzele se colorează într-un amestec de galben, auriu şi orange. Florile sunt albe, parfumate, în raceme de 15-30 cm lungime. Înfloreşte primăvara devreme, cu o puternică înflorire o dată la 2-3 ani. Fructul este o păstaie cu 2-6 seminţe. Origine și răspândire: Nativ în estul S.U.A. Utilizări: Este larg răspândit ca arbore Cultură: Suportă toate tipurile de soluri şi necesită un bun ornamental datorită florilor sale. Au fost create drenaj şi un sol umed. Poate creşte şi pe solurile foarte alcaline. multe varietăţi decorative. Numele de lemn Nu tolerează umbra. Inmultirea este dificilă. galben derivă de la măduva sa galbenă, folosită de unii specialişti pentru mobilier. Description: It is a small to medium-sized tree, with a broad, rounded crown and smooth gray bark. The leaves are compound pinnate, with 5-11 alternately arranged leaflets, each leaflet with an acute apex, with an entire margin and a thinly to densely hairy underside. In the fall, the leaves turn a mix of yellow, gold, and orange. The flowers are fragrant, white, arranged in racemes 15-30 cm long. Blooms in early summer and is variable from year to year, with heavy flowering every second or third year. The fruit is a pod containing 2-6 seeds. -

Reconstructing the Deep-Branching Relationships of the Papilionoid Legumes

SAJB-00941; No of Pages 18 South African Journal of Botany xxx (2013) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect South African Journal of Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Reconstructing the deep-branching relationships of the papilionoid legumes D. Cardoso a,⁎, R.T. Pennington b, L.P. de Queiroz a, J.S. Boatwright c, B.-E. Van Wyk d, M.F. Wojciechowski e, M. Lavin f a Herbário da Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (HUEFS), Av. Transnordestina, s/n, Novo Horizonte, 44036-900 Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil b Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20A Inverleith Row, EH5 3LR Edinburgh, UK c Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape, Modderdam Road, \ Bellville, South Africa d Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P. O. Box 524, 2006 Auckland Park, Johannesburg, South Africa e School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501, USA f Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA article info abstract Available online xxxx Resolving the phylogenetic relationships of the deep nodes of papilionoid legumes (Papilionoideae) is essential to understanding the evolutionary history and diversification of this economically and ecologically important legume Edited by J Van Staden subfamily. The early-branching papilionoids include mostly Neotropical trees traditionally circumscribed in the tribes Sophoreae and Swartzieae. They are more highly diverse in floral morphology than other groups of Keywords: Papilionoideae. For many years, phylogenetic analyses of the Papilionoideae could not clearly resolve the relation- Leguminosae ships of the early-branching lineages due to limited sampling. -

Preliminary Checklist of the Terrestrial Flora and Fauna of Fern Cave

Preliminary Checklist of the Terrestrial Flora and Fauna of Fern Cave National Wildlife Refuge ______________________________________________ Prepared for: United States Fish & Wildlife Service Prepared by: J. Kevin England, MAT David Richardson, MS Completed: as of 22 Sep 2019 All rights reserved. Phone: 256-565-4933 Email: [email protected] Flora & Fauna of FCNWR2 ABSTRACT I.) Total Biodiversity Data The main objective of this study was to inventory and document the total biodiversity of terrestrial habitats located at Fern Cave National Wildlife Refuge (FCNWR). Table 1. Total Biodiversity of Fern Cave National Wildlife Refuge, Jackson Co., AL, USA Level of Classification Families Genera Species Lichens and Allied Fungi 14 21 28 Bryophytes (Bryophyta, Anthocerotophyta, Marchantiophyta) 7 9 9 Vascular Plants (Tracheophytes) 76 138 176 Insects (Class Insecta) 9 9 9 Centipedes (Class Chilopoda) 1 1 1 Millipedes (Class Diplopoda) 2 3 3 Amphibians (Class Amphibia) 3 4 5 Reptiles (Class Reptilia) 2 3 3 Birds (Class Aves) 1 1 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 2 2 2 Total 117 191 237 II. Vascular Flora (Appendix 3) Methods and Materials To compile a thorough vascular flora survey, several examples of different plant communities at numerous sites were visited and sampled during the study. Approximately 45 minutes was spent documenting community structure at each site. Lastly, all habitats, ecological systems, and plant associations found within the property boundaries were defined based on floristic content, soil characteristics (soil maps) and other abiotic factors. Flora & Fauna of FCNWR3 The most commonly used texts for specimen identification in this study were Flora of North America (1993+), Mohr (1901), Radford et al. -

Cladrastis Kentukea American Yellowwood1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-170 November 1993 Cladrastis kentukea American Yellowwood1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Yellowwood is so-named because the freshly-cut heartwood is a muted to brilliant yellow color, and the wood is known to yield a yellow dye (Fig. 1). This seldom-used, native, deciduous tree makes a very striking specimen or shade tree, reaches 30 to 50, rarely 75 feet in height, with a broad, rounded canopy, and has a vase-shaped, moderately dense silhouette. Smooth, grey to brown bark, bright green, pinnately compound, 8 to 12-inch-long leaflets, and a strikingly beautiful display of white, fragrant blossoms make Yellowwood a wonderful choice for multiple landscape uses. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Cladrastis kentukea Pronunciation: kluh-DRASS-tiss ken-TUCK-ee-uh Common name(s): American Yellowwood, Virgilia Family: Leguminosae USDA hardiness zones: 4 through 8 (Fig. 2) Origin: native to North America Figure 1. Young American Yellowwood. Uses: recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or for median strip plantings in the highway; Crown density: moderate shade tree; specimen; residential street tree Growth rate: medium Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out Texture: medium of the region to find the tree Foliage DESCRIPTION Leaf arrangement: alternate (Fig. 3) Height: 30 to 50 feet Leaf type: odd pinnately compound Spread: 40 to 50 feet Leaflet margin: entire Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette Leaflet shape: elliptic (oval); ovate Crown shape: round; vase shape 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-170, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Indiana County Endangered, Threatened and Rare Species List 03/09/2020 County: Brown

Page 1 of 2 Indiana County Endangered, Threatened and Rare Species List 03/09/2020 County: Brown Species Name Common Name FED STATE GRANK SRANK Mollusk: Bivalvia (Mussels) Villosa lienosa Little Spectaclecase SSC G5 S3 Insect: Coleoptera (Beetles) Cicindela patruela A Tiger Beetle SR G3 S3 Insect: Lepidoptera (Butterflies & Moths) Autochton cellus Gold-banded Skipper SE G4 S1 Hyperaeschra georgica A Prominent Moth ST G5 S2 Insect: Odonata (Dragonflies & Damselflies) Rhionaeschna mutata Spatterdock Darner ST G4 S2S3 Tachopteryx thoreyi Gray Petaltail WL G4 S3 Amphibian Acris blanchardi Blanchard's Cricket Frog SSC G5 S4 Reptile Clonophis kirtlandii Kirtland's Snake SE G2 S2 Crotalus horridus Timber Rattlesnake SE G4 S2 Opheodrys aestivus Rough Green Snake SSC G5 S3 Opheodrys vernalis Smooth Green Snake SE G5 S2 Terrapene carolina carolina Eastern Box Turtle SSC G5T5 S3 Bird Accipiter striatus Sharp-shinned Hawk SSC G5 S2B Aimophila aestivalis Bachman's Sparrow G3 SXB Ammodramus henslowii Henslow's Sparrow SE G4 S3B Antrostomus vociferus Whip-poor-will SSC G5 S4B Buteo platypterus Broad-winged Hawk SSC G5 S3B Cistothorus platensis Sedge Wren SE G5 S3B Dendroica virens Black-throated Green Warbler G5 S2B Haliaeetus leucocephalus Bald Eagle SSC G5 S2 Helmitheros vermivorus Worm-eating Warbler SSC G5 S3B Ixobrychus exilis Least Bittern SE G4G5 S3B Mniotilta varia Black-and-white Warbler SSC G5 S1S2B Setophaga cerulea Cerulean Warbler SE G4 S3B Setophaga citrina Hooded Warbler SSC G5 S3B Mammal Lasiurus borealis Eastern Red Bat SSC G3G4 S4 -

Climatic Range Filling of North American Trees Benjamin Seliger University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Fall 12-14-2018 Climatic Range Filling of North American Trees Benjamin Seliger University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Other Earth Sciences Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Other Life Sciences Commons, Other Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, Paleobiology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Seliger, Benjamin, "Climatic Range Filling of North American Trees" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2994. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2994 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATIC RANGE FILLING OF NORTH AMERICAN TREES By Benjamin James Seliger B.S. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2013 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Ecology and Environmental Sciences) The Graduate School The University of Maine December 2018 Advisory Committee Jacquelyn L. Gill, Assistant Professor of Paleoecology and Plant Ecology (Advisor) David E. Hiebeler, Professor of Mathematics -

Yellowwood Cladrastis Kentukea

Yellowwood Cladrastis kentukea Cladrastis is from the Greek klados and thraustos which mean “branch” and “fragile” in reference to the brittle wood; kentukea means “of Kentucky.” Yellowwood is named for the bright yellow heartwood. Other names include American yellowwood and virgilia. Yellowwood is a rare tree native to isolated locations across the southeastern United States from North Carolina to Kentucky and Tennessee. Various references show it scattered in Indiana, Illinois, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. Yellowwod typically occurs in rich, well drained limestone soils in river valleys, slopes and ridges along streams. Yellowwood is the only species of Cladrastis that is native to North America. Yellowwood is among the rarest of trees in the eastern United States, but it is not ranked as a plant of conservation concern by the Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. Yellowwood is a medium sized, deciduous tree with a vase like form. It typically forks repeatedly and develops a broad rounded crown in full sun, but maintains a single tall stem much narrower form under dense shade. This tree typically grows 33 to 49 feet tall, exceptionally to 89 feet tall, with a broad rounded crown and smooth gray bark. The leaves are compound pinnate, 5 to 11 (mostly 7 to 9) alternately arranged leaflets. The leaflets range from 6 to 13 cm long and 3 to 7 cm broad with a thinly to densely hairy underside. In the summer the leaflets are green and in the fall, the leaves turn a mix of yellow, gold and orange. Flowers bloom every 2 or 3 years and are fragrant, white, pea like flowers that hang from branches in late spring in 8 to 14 inch clusters, which makes it a beautiful ornamental tree. -

Cladrastis Kentukea

Cladrastis kentukea - American Yellowwood (Fabaceae) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Cladrastis kentukea is a striking tree with long -odd-pinnately compound panicles of fragrant white flowers in June. American -2-4" long x half as wide Yellowwood has bright green foliage that contrasts -usually 7-9 leaflets, each elliptic to ovate nicely with darker leaved trees and turns golden- -bright green, terminal leaflet largest yellow in autumn. It's an excellent small shade tree -petiole enlarged at base and enclosing bud for smaller properties, as a single specimen or in -foliage often turns copper to yellow in autumn groupings. Flowers FEATURES -small (each about 1") Form -in pendulous clusters -medium to large ornamental/shade, deciduous tree -fragrant, white, -maturing at 40-50' tall x 20-50' wide -flowers bloom in late spring -rounded vase, symmetrical form -highly ornamental -often multi-trunked Fruits -medium to slow growth rate (less than 12" per year) -pods (legume) -3-5" long -turn brown in autumn -held late in the tree, giving winter effect Twigs -green becoming brown, smooth, lustrous, many small lenticels Trunk -smooth, gray to brown (like beech) -freshly cut wood is bright yellow (dye was used in the past) -branches initiate low to the ground Culture -full sun (best) to partial shade USAGE -prefers moist, organic soils that drain well, but is Function adaptable to poor soils, dry soils, and soils of various -accent or street tree, buffer strip, shade tree, pH; does not tolerate wet soils reclamation -may be somewhat difficult to transplant -use in lawn, park, golf course, residential -Prune only in summer. Winter or spring pruning Texture results in profuse bleeding. -

Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Mammoth Cave National Park

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND PLANT COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR MAMMOTH CAVE NATIONAL PARK Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Network Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office February 2010 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific basis for effective conservation action. A NatureServe Technical Report Prepared for the National Park Service under Cooperative Agreement H 5028 01 0435. Citation: Milo Pyne, Erin Lunsford Jones, and Rickie White. 2010. Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Mammoth Cave National Park. Durham, North Carolina: NatureServe. © 2010 NatureServe NatureServe Southern U. S. Regional Office 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama Street, S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at http://www.natureserve.org/explorer/ Cover photo: Mature Interior Low Plateau mesophytic forest above the Green River, Mammoth Cave National Park - Photo by Milo Pyne ii Acknowledgments This report was compiled thanks to a team including staff from the National Park Service and NatureServe. -

The Vascular Flora of the Natchez Trace Parkway

THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE NATCHEZ TRACE PARKWAY (Franklin, Tennessee to Natchez, Mississippi) Results of a Floristic Inventory August 2004 - August 2006 © Dale A. Kruse, 2007 © Dale A. Kruse 2007 DATE SUBMITTED 28 February 2008 PRINCIPLE INVESTIGATORS Stephan L. Hatch Dale A. Kruse S. M. Tracy Herbarium (TAES), Texas A & M University 2138 TAMU, College Station, Texas 77843-2138 SUBMITTED TO Gulf Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Lafayette, Louisiana CONTRACT NUMBER J2115040013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The “Natchez Trace” has played an important role in transportation, trade, and communication in the region since pre-historic times. As the development and use of steamboats along the Mississippi River increased, travel on the Trace diminished and the route began to be reclaimed by nature. A renewed interest in the Trace began during, and following, the Great Depression. In the early 1930’s, then Mississippi congressman T. J. Busby promoted interest in the Trace from a historical perspective and also as an opportunity for employment in the area. Legislation was introduced by Busby to conduct a survey of the Trace and in 1936 actual construction of the modern roadway began. Development of the present Natchez Trace Parkway (NATR) which follows portions of the original route has continued since that time. The last segment of the NATR was completed in 2005. The federal lands that comprise the modern route total about 52,000 acres in 25 counties through the states of Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. The route, about 445 miles long, is a manicured parkway with numerous associated rest stops, parks, and monuments. Current land use along the NATR includes upland forest, mesic prairie, wetland prairie, forested wetlands, interspersed with numerous small agricultural croplands.