Milford Mills and the Creation of a Gentry Powerbase: the Alexanders of Co

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carlow Scheme Details 2019.Xlsx

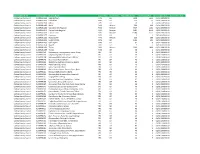

Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Source Type Population Served Volume Supplied Scheme Start Date Scheme End Date Carlow County Council 0100PUB1161 Bagenalstown PWS GR 2902 1404 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1166 Ballinkillen PWS GR 101 13 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1106Bilboa PWS GR 36 8 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1162 Borris PWS Mixture 552 146 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1134 Carlow Central Regional PWS Mixture 3727 1232 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1142 Carlow North Regional PWS Mixture 9783 8659 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1001 Carlow Town PWS Mixture 16988 4579 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1177Currenree PWS GR 9 2 18/10/2013 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1123 Hacketstown PWS Mixture 599 355 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1101 Leighlinbridge PWS GR 1144 453 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1103 Old Leighlin PWS GR 81 9 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1178Slyguff PWS GR 9 2 18/10/2013 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1131 Tullow PWS Mixture 3030 1028 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1139Tynock PWS GR 26 4 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4063 Ballymurphy Housing estate, Inse-n-Phuca, PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4010 Ballymurphy National School PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4028 Ballyvergal B&B, Dublin Road, CARLOW PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4076 Beechwood Nursing Home. -

Ethnic Diversity in Politics and Public Life

BRIEFING PAPER CBP 01156, 22 October 2020 By Elise Uberoi and Ethnic diversity in politics Rebecca Lees and public life Contents: 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 2. Parliament 3. The Government and Cabinet 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 5. Public sector organisations www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Ethnic diversity in politics and public life Contents Summary 3 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 6 1.1 Categorising ethnicity 6 1.2 The population of the United Kingdom 7 2. Parliament 8 2.1 The House of Commons 8 Since the 1980s 9 Ethnic minority women in the House of Commons 13 2.2 The House of Lords 14 2.3 International comparisons 16 3. The Government and Cabinet 17 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 19 4.1 Devolved legislatures 19 4.2 Local government and the Greater London Authority 19 5. Public sector organisations 21 5.1 Armed forces 21 5.2 Civil Service 23 5.3 National Health Service 24 5.4 Police 26 5.4 Justice 27 5.5 Prison officers 28 5.6 Teachers 29 5.7 Fire and Rescue Service 30 5.8 Social workers 31 5.9 Ministerial and public appointments 33 Annex 1: Standard ethnic classifications used in the UK 34 Cover page image copyright UK Youth Parliament 2015 by UK Parliament. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 / image cropped 3 Commons Library Briefing, 22 October 2020 Summary This report focuses on the proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in a range of public positions across the UK. -

Junior Youth Retreat Overnight Youth Retreat

Rev. Fr. John Dunphy: Phone: 059 / 9141833 / 9182882 Priest on Call for Carlow Area: (Emergency Only)Phone: - 087/2588118 Wheat and Weeds Finance Committee:- monthly meeting this Thursday 27th July @ 8.30pm in the Jesus compares the Kingdom of Heaven to a field in which the Parish Centre. master has sown good seed. In the night, an enemy comes and plants weeds, so when the crop grows it is a mixture of Pre-Baptism meeting:- next meeting wheat and weed. The servants’ instinct is to pull the weeds out, but the master Monday 4th September @ 7pm in the demands that the bad grow alongside the good … he himself will sort the Parish Centre. wheat from the weeds at the final harvest. Governey Park Mass:- the annual Mass It’s a typical Palestinian problem, the darnel weed, which looks just like wheat will take place this Thursday 27th July @ in its early stages is a menace to the harvest. The roots of the darnel weed 7.30pm on the green in Staunton Avenue. intertwine with the roots of the wheat. All are welcome. To pull the darnel out can jeopardise the harvest. Similarly just as it’s hard to th tell the difference between wheat and darnel, so it’s not always easy for us to Commemorating the 100 Anniversary of tell the difference between good and evil. A bad person can change and Very Rev Fr. Hugh Cullen P.P. of Graigue become good, and a seemingly good person might not be as virtuous as we – Killeshin (1909-1917):- To imagine. -

Weekly Lists

Date: 30/04/2021 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 2:39:22 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 19/04/2021 To 23/04/2021 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED LOCATION RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 21/421 Julie O'Farrell P 20/04/2021 (a) demolition of a single storey shed to the side N N N of the existing dwelling (b) the construction of (i) a single storey extension at ground level to the front of the existing dwelling and (ii) a single storey bay window extension at ground level to the rear of the existing dwelling including all associated internal alterations and site landscaping works. This is an Architectural Conservation Area Dromany St Vincents Road Greystones Co. Wicklow 21/422 Mark Bayley P 19/04/2021 1. Demolition of existing single storey extension N N N 2. Construction of a single storey extension to side and rear of existing dwelling and 3. all ancillary site works Brook Cottage Kilpipie Lower Aughrim Co. Wicklow Y14 T276 Date: 30/04/2021 WICKLOW COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 2:39:23 PM PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 19/04/2021 To 23/04/2021 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. -

Road Schedule for County Laois

Survey Summary Date: 21/06/2012 Eng. Area Cat. RC Road Starting At Via Ending At Length Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-0 3 Roads in Killinure called Mountain Farm, Rockash, ELECTORAL BORDER 7276 Burkes Cross The Cut, Ross Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-73 ELECTORAL BORDER ROSS BALLYFARREL 6623 Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-139 BALLYFARREL BELLAIR or CLONASLEE 830.1 CAPPANAPINION Central Eng Area L LP L-1030-0 3 Roads at Killinure School Inchanisky, Whitefields, 3 Roads South East of Lacca 1848 Lacka Bridge in Lacca Townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-0 3 Roads at Roundwood Roundwood, Lacka 3 Roads South East of Lacca 2201 Bridge in Lacca Townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-22 3 Roads South East of Lacca CARDTOWN 3 Roads in Cardtown 1838 Bridge in Lacca Townsland townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-40 3 Roads in Cardtown Johnsborough., Killeen, 3 Roads at Cappanarrow 2405 townsland Ballina, Cappanrrow Bridge Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-64 3 Roads at Cappanarrow Derrycarrow, Longford, DELOUR BRIDGE 2885 Bridge Camross Central Eng Area L LP L-1034-0 3 Roads in Cardtown Cardtown, Knocknagad, 4 Roads in Tinnakill called 3650 townsland Garrafin, Tinnakill Tinnakill X Central Eng Area L LP L-1035-0 3 Roads in Lacca at Church Lacka, Rossladown, 4 Roads in Tinnakill 3490 of Ireland Bushorn, Tinnahill Central Eng Area L LP L-1075-0 3 Roads at Paddock School Paddock, Deerpark, 3 Roads in Sconce Lower 2327 called Paddock X Sconce Lower Central Eng Area L LP L-1075-23 3 Roads in Sconce Lower Sconce Lower, Briscula, LEVISONS X 1981 Cavan Heath Survey Summary Date: 21/06/2012 Eng. -

Chapter 15 Town and Village Plans / Rural Nodes

Town and Village Plans / Settlement Boundaries CHAPTER 15 TOWN AND VILLAGE PLANS / RURAL NODES Draft Carlow County Development Plan 2022-2028 345 | P a g e Town and Village Plans / Settlement Boundaries Chapter 15 Town and Village Plans / Rural Nodes 15.0 Introduction Towns, villages and rural nodes throughout strategy objectives to ensure the sustainable the County have a key economic and social development of County Carlow over the Plan function within the settlement hierarchy of period. County Carlow. The settlement strategy seeks to support the sustainable growth of these Landuse zonings, policies and objectives as settlements ensuring growth occurs in a contained in this Chapter should be read in sustainable manner, supporting and conjunction with all other Chapters, policies facilitating local employment opportunities and objectives as applicable throughout this and economic activity while maintaining the Plan. In accordance with Section 10(8) of the unique character and natural assets of these Planning and Development Act 2000 (as areas. amended) it should be noted that there shall be no presumption in law that any land zoned The Settlement Hierarchy for County Carlow is in this development plan (including any outlined hereunder and is contained in variation thereof) shall remain so zoned in any Chapter 2 (Table 2.1). Chapter 2 details the subsequent development plan. strategic aims of the core strategy together with settlement hierarchy policies and core Settlement Settlement Description Settlements Tier Typology 1 Key Town Large population scale urban centre functioning as self – Carlow Town sustaining regional drivers. Strategically located urban center with accessibility and significant influence in a sub- regional context. -

Cliffe / Vigors Estate 1096

Private Sources at the National Archives Cliffe / Vigors Estate 1096 1 ACCESSION NO. 1096 DESCRIPTION Family and Estate papers of the Cliffe / Vigors families, Burgage, Old Leighlin, Co. Carlow. 17th–20th centuries DATE OF ACCESSION 16 March 1979 ACCESS Open 2 1096 Cliffe / Vigors Family Papers 1 Ecclesiastical 1678–1866 2 Estate 1702–1902 3 Household 1735–1887 4 Leases 1673–1858 5 Legal 1720–1893 6 Photographs c.1862–c.1875 7 Testamentary 1705–1888 8 John Cliffe 1729–1830 9 Robert Corbet 1779–1792 10 Dyneley Family 1846–1932 11 Rev. Edward Vigors (1747–97) 1787–1799 12 Edward Vigors (1878–1945) 1878–1930 13 John Cliffe Vigors (1814–81) 1838–1880 14 Nicholas Aylward Vigors (1785–1840) 1800–1855 15 Rev. Thomas M. Vigors (1775–1850) 1793–1851 16 Thomas M.C. Vigors (1853–1908) 1771–1890 17 Cliffe family 1722–1862 18 Vigors family 1723–1892 19 Miscellaneous 1611–1920 3 1096 Cliffe / Vigors Family Papers The documents in this collection fall into neat groups. By far the largest section is that devoted to the legal work of Bartholomew Cliffe, Exchequer Attorney, who resided at New Ross. Many members of the Cliffe family were sovereigns and recorders of New Ross (Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, vol. ix, 1889, 312–17.) Besides intermarrying with their cousins, the Vigors, the Cliffe family married members of the Leigh and Tottenham families, these were also prominent in New Ross life (Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland), [op. cit.]. Col Philip Doyne Vigors (1825–1903) was a Vice President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. -

GAA Competition Report

Wicklow Centre of Excellence Ballinakill Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Rathdrum Co. Wicklow. Co. Wicklow Master Fixture List 2019 A67 HW86 15-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Baltinglass 20:00 Baltinglass V Kiltegan Referee: Kieron Kenny Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V St Patrick's Wicklow Referee: Noel Kinsella 17-02-2019 (Sun) Division 1 Senior Football League Round 2 Blessington 11:00 Blessington V AGB Referee: Pat Dunne Rathnew 11:00 Rathnew V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Division 1A Senior Football League Round 2 Kilmacanogue 11:00 Kilmacanogue V Bray Emmets Gaa Club Referee: Phillip Bracken Carnew 11:00 Carnew V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Darragh Byrne Newtown GAA 11:00 Newtown V Annacurra Referee: Stephen Fagan Dunlavin 11:00 Dunlavin V Avondale Referee: Garrett Whelan 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Hollywood 20:00 Hollywood V Avoca Referee: Noel Kinsella Division 1 Senior Football League Round 3 Baltinglass 19:30 Baltinglass V Tinahely Referee: John Keenan Page: 1 of 38 22-02-2019 (Fri) Division 1A Senior Football League Round 3 Annacurra 20:00 Annacurra V Carnew Referee: Anthony Nolan 23-02-2019 (Sat) Division 3 Football League Round 1 Knockananna 15:00 Knockananna V Tinahely Referee: Chris Canavan St. Mary's GAA Club 15:00 Enniskerry V Shillelagh / Coolboy Referee: Eddie Leonard 15:00 Lacken-Kilbride V Blessington Referee: Liam Cullen Aughrim GAA Club 15:00 Aughrim V Éire Óg Greystones Referee: Brendan Furlong Wicklow Town 16:15 St Patrick's Wicklow V Ashford Referee: Eugene O Brien Division -

2019 Week 25 17.06.19 – 21.06.19

DATE : 01/07/2019 LAOIS COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:19:48 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 17/06/19 TO 21/06/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/342 Catherine Molyneaux P 17/06/2019 change the use of building from school to residential dwelling, new septic tank and all associated works Gorteen Cullahill Portlaoise Co.Laois 19/343 James Ward P 17/06/2019 construct new dwelling house, domestic garage, waste water treatment system with polishing filter, new bored well and new site entrance Ballinalug Rosenallis Co.Laois 19/344 Gerry Farrell P 17/06/2019 construct an agricultural shed and all ancillary site development works Barrowhouse Athy Co.Laois 19/345 Denis & Zofia McEvoy P 17/06/2019 change design of dwelling house from that granted under file no. 18/360 and all associated site works Raggettstown Ballinakill Co.Laois DATE : 01/07/2019 LAOIS COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:19:48 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 17/06/19 TO 21/06/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. -

SUMMER CAMPS in CO. WICKLOW 2016 Early Years Location Dates Theme Price (€) Contact Service

SUMMER CAMPS IN CO. WICKLOW 2016 Early Years Location Dates Theme Price (€) Contact Service Nexus Preschool & Theatre Lane, 4th July to Mixed themes each week. €80 per week with 10% Kerrylee or Kristine 0864680758 or The After School Hillside Rd, 29th August Please see website sibling discount and all [email protected] Club Greystones www.theafterschoolclub.ie snacks and excursions included. Honeycomb Kilcoole 13th July and Summer camp for children €50 Samantha Byrne 083 3408480 Montessori 20th July aged 3-6 years. Each week there will be a different theme that will include lots of arts and crafts with lots of fun and games outside in our garden. Park Academy Park Academy 4th July – 26th Survival Camp 8.30am -2.00pm Allison or Siobhan on 01 2851237 Childcare Childcare Bray, August – €125 per week Southern Culinary School Camp Cross Rd, Bray Different 7.30am-6.30pm theme every Little Einsteins Science €210 per week Park Academy week Camp Childcare Eden Gate, Let’s Build it Camp Greystones, Co. Wicklow Around the World and Back Camp JUMP Sports Camp Time for the Oscars Camp SUMMER CAMPS IN CO. WICKLOW 2016 Redcross Montessori Redcross Monday 18th Theme: Fun Science €55 per week, includes Amanda Jordan on 087 2144041 Pre-school - Friday 22nd Experiments; Arts & Crafts; lunch. July. Lots of fun outdoor 10am - 1pm activities daily KangaKare Woodlands, Throughout Camp age ranges 1-9 years. 9am-12noon - €15 per Mandy 0402 33344 Arklow Lamberton, July & Different theme each week session. [email protected] Arklow August, Art & Craft; Lego; Science; 8am-2pm €33 per day. -

14Th February, 2021

LEIGHLIN PARISH NEWSLETTER 1 4 T H FEBRUARY 2 0 2 1 6 T H S U N DAY I N ORDINARY T I M E Contact Details: Ash Wednesday Fr Pat Hennessy “Loving Jesus, 059 9721463 As I place on my forehead the sign of your saving cross Deacon Patrick Roche You say to me, repent and believe in the Gospel. 083 1957783 Walking into Lent, My heart is set on you. Parish Centre May my fasting fill me with hunger for you, 059 9722607 May my prayer draw me deeper into your presence. Parish Mobile May my acts of charity bring your love to my home and 085 7714309 community. Email: Lord of life, grant that by turning back to you in these forty days [email protected] I will re-awaken the joy of my Easter faith; Live Webcam For you raise me up from fear and despair And call me to hope and trust in God who is with me always. www.leighlinparish.ie With you, I will rise again. Amen”. Mass Times: Leighlinbridge Webcam No Public Masses To view Webcam log on to www.leighlinparish.ie This will open Mass via webcam the website home page. Scroll sown to see Leighlinbridge and Ballinabranna webcams on right hand side. Click on picture of Sat 7.30pm church and then the red arrow in centre of picture to view. Sunday 11am Open for Private Prayer Mass Times via Webcam 12 - 4.30pm Monday to Friday 9.30am Mon-Fri 9.30am Ash Wednesday 7.30pm Ash Wednesday Vigil Saturday 7.30pm 7.30pm Open for Private Prayer Sunday 11am 10.30 - 4.30pm Donations to Parish Collections Ballinabranna Currently the Office are unable to issue the annual envelopes to No Public Masses parishioners. -

Sunday 26Th July 2015

Recent Deaths: Ann - Christine Cree (née Pickles) Ballyknockan and formerly Yorkshire LEIGHLIN PARISH NEWSLETTER Months Mind: 2 6 T H J U L Y 2015 James Earl, Clogrennane, Mass on Sunday 26th July at 9.30am in Ballinabranna Contact Details: 1 7 T H S U N D A Y O F ORDINARY T I M E Michael (Mick) Geraghty, Mass on Sunday 2nd August at 9.30am in Ballinabranna Fr Tom Lalor 087 2360355 The First Day of the Week 1st Anniversaries: Ger Monaghan, High Street, Mass on Saturday 25th July at 7.30pm in Leighlinbridge Parish Centre Sunday the first day of the week is “D day” for Christians. Teresa Kelly, Johnduffswood, Mass on Sunday 26th July at 11am in Leighlinbridge 059 9722607 Sheila Bolger, 13 New Road, Mass on Saturday 1st August at 7.30pm in Leighlinbridge Christians are called upon to gather weekly to pray & Email: celebrate the Death & Resurrection of Christ - in Mass. Anniversaries: [email protected] Mary Nolan & her son Ger Nolan, Augharue Michael (Mikey) Dermody, Oldtown This has been the honoured practice Deceased Members of Sieber Family Web: Joe Earl & deceased members of Earl Family, Rathellen www.leighlinparish.ie since the time of the Apostles. John & Claire Comerford, Seskinrea Mass Times: Hannah McGrath, Rathellen The Irish name, De Domhnaigh - The Lord’s Day Angela & Marc Sheehy, Askea Lawns, Carlow Leighlinbridge Teresa Kelliher, Dungarvan - captures well its spirit. Paddy Doyle, Carlow Road Saturday 7.30pm Sunday 11am It is a day when we are willing to ___________________________________ Mon, Tues, Weds, & Thurs 9.30am Notices “waste” time with the Lord.