Revisiting Skaz in Ivan Vyrypaev's Cinema And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Rowson Phd Thesis Politics and Putinism a Critical Examination

Politics and Putinism: A Critical Examination of New Russian Drama James Rowson A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Royal Holloway, University of London Department of Drama, Theatre & Dance September 2017 1 Declaration of Authorship I James Rowson hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This thesis will contextualise and critically explore how New Drama (Novaya Drama) has been shaped by and adapted to the political, social, and cultural landscape under Putinism (from 2000). It draws on close analysis of a variety of plays written by a burgeoning collection of playwrights from across Russia, examining how this provocative and political artistic movement has emerged as one of the most vehement critics of the Putin regime. This study argues that the manifold New Drama repertoire addresses key facets of Putinism by performing suppressed and marginalised voices in public arenas. It contends that New Drama has challenged the established, normative discourses of Putinism presented in the Russian media and by Putin himself, and demonstrates how these productions have situated themselves in the context of the nascent opposition movement in Russia. By doing so, this thesis will offer a fresh perspective on how New Drama’s precarious engagement with Putinism provokes political debate in contemporary Russia, and challenges audience members to consider their own role in Putin’s autocracy. The first chapter surveys the theatrical and political landscape in Russia at the turn of the millennium, focusing on the political and historical contexts of New Drama in Russian theatre and culture. -

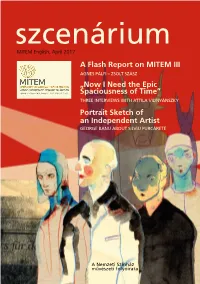

A Flash Report on MITEM III „Now I Need the Epic Spaciousness of Time” Portrait Sketch of an Independent Artist

szcenárium MITEM English, April 2017 A Flash Report on MITEM III ÁGNES PÁLFI – ZSOLT SZÁSZ „Now I Need the Epic Spaciousness of Time” THREE INTERVIEWS WITH ATTILA VIDNYÁNSZKY Portrait Sketch of an Independent Artist GEORGE BANU ABOUT SILVIU PURCĂRETE A Nemzeti Színház művészeti folyóirata szcenárium MITEM English, April 2017 contents inaugural Zsolt Szász: “Grasp the Life of Man Complete!” • 3 Three Interviews with Attila Vidnyánszky • 5 Dialogue with the Spectators (by Vera Prontvai) • 6 “Now I Need the Epic Spaciousness of Time” (by Zsolt Szász) • 9 “We are Now Witnessing a Welcome Change in Pace” (by Zsolt Szász) • 18 (Translated by Dénes Albert and Anikó Kocsis) mitem 2016 Ágnes Pálfi – Zsolt Szász: It Has Been a Real Inauguration of Theatre! A Flash Report on MITEM III (Translated by Nóra Durkó) • 23 Justyna Michalik: Tadeusz Kantor’s Experiments in the Theatre Notes for The Space of Memory Exhibition (Translated by András Pályi and Anikó Kocsis) • 43 mitem 2017 Dostoevsky in Kafka’s Clothes An Interview With Valery Fokin by Sándor Zsigmond Papp (Translated by Dénes Albert) • 55 Why Did We Kill Romanticism? An Interview With Stage Director David Doiashvili by György Lukácsy (Translated by Dénes Albert) • 59 “Self-Expression Was Our Rebellion” An Interview With Eugenio Barba by Rita Szentgyörgyi (Translated by Anikó Kocsis) • 63 Eugenio Barba: Eurasian Theatre • 67 George Banu: Silviu Purcărete Portrait Sketch of an Independent Artist (Translated by Eszter Miklós and Dénes Albert) • 75 Helmut Stürmer: Poet of the Italian Tin Box (Translated -

Friday, December 7, 2018

Friday, December 7, 2018 Registration Desk Hours: 7:00 AM – 5:00 PM, 4th Floor Exhibit Hall Hours: 9:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 3rd Floor Audio-Visual Practice Room: 7:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 4th Floor, office beside Registration Desk Cyber Cafe - Third Floor Atrium Lounge, 3 – Open Area Session 4 – Friday – 8:00-9:45 am Committee on Libraries and Information Resources Subcommittee on Copyright Issues - (Meeting) - Rhode Island, 5 4-01 War and Society Revisited: The Second World War in the USSR as Performance - Arlington, 3 Chair: Vojin Majstorovic, Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (Austria) Papers: Roxane Samson-Paquet, U of Toronto (Canada) "Peasant Responses to War, Evacuation, and Occupation: Food and the Context of Violence in the USSR, June 1941–March 1942" Konstantin Fuks, U of Toronto (Canada) "Beyond the Soviet War Experience?: Mints Commission Interviews on Nazi-Occupied Latvia" Paula Chan, Georgetown U "Red Stars and Yellow Stars: Soviet Investigations of Nazi Crimes in the Baltic Republics" Disc.: Kenneth Slepyan, Transylvania U 4-02 Little-Known Russian and East European Research Resources in the San Francisco Bay Area - Berkeley, 3 Chair: Richard Gardner Robbins, U of New Mexico Papers: Natalia Ermakova, Western American Diocese ROCOR "The Russian Orthodox Church and Russian Emigration as Documented in the Archives of the Western American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia" Galina Epifanova, Museum of Russian Culture, San Francisco "'In Memory of the Tsar': A Review of Memoirs of Witnesses and Contemporaries of Emperor Nicholas II from the Museum of Russian Culture of San Francisco" Liladhar R. -

War, Patriotism and Desertion in Pavel Pryazhko's the Soldier

Studies in Theatre and Performance ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rstp20 ‘He did not go back to the army’: war, patriotism and desertion in Pavel Pryazhko’s The Soldier James Rowson To cite this article: James Rowson (2021): ‘He did not go back to the army’: war, patriotism and desertion in Pavel Pryazhko’s TheSoldier, Studies in Theatre and Performance, DOI: 10.1080/14682761.2021.1917873 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2021.1917873 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 23 Apr 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 44 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rstp20 STUDIES IN THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2021.1917873 ‘He did not go back to the army’: war, patriotism and desertion in Pavel Pryazhko’s The Soldier James Rowson East 15 Acting School, University of Essex, Southend-on-Sea, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Over the past twenty years, a collection of theatre makers in Russia The soldier; pavel pryazhko; have staged suppressed and marginalised voices to engage with new drama; teatr.doc; the political and social realities of contemporary Russia. The work of russian theatre; vladimir these innovative theatre practitioners has been collated under the putin idiom of New Drama (Novaya Drama). Previous studies of New Drama have placed an emphasis on the role of the text and the playwright’s dynamic use of contemporary language. -

Cinematic Taganrog

Alexander Fedorov Cinematic Taganrog Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Cinematic Taganrog. Moscow: "Information for all", 2021. 100 p. The book provides a brief overview of full–length feature films and TV series filmed in Taganrog (taking into account the opinions of film critics and viewers), provides a list of actors, directors, cameramen, screenwriters, composers and film experts who were born, studied and / or worked in Taganrog. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 2 Table of contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Movies filmed in Taganrog and its environs ………………………………………….. 5 Cinematic Taganrog: Who is Who…………………………….…………………………. 69 Anton Barsukov: “How I was filming with Nikita Mikhalkov, Victor Merezhko and Andrey Proshkin.………………………………………………… 77 Filmography (movies, which filmed in Taganrog and its surroundings)…… 86 About the Author……………………………………………………………………………….. 92 References ………………………………………………………………………………………… 97 3 Introduction What movies were filmed in Taganrog? How did the press and viewers evaluate and rate these films? What actors, directors, cameramen, screenwriters, film composers, film critics were born and / or studied in this city? In this book, for the first time, an attempt is made to give a wide panorama of nearly forty Soviet and Russian movies and TV series filmed in Taganrog and its environs, in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers. Unfortunately, data are not available for all such films (therefore, the book, for example, does not include many documentaries). The book cites articles and reviews of Soviet and Russian film critics, audience reviews on the Internet portals "Kino –teater.ru" and "Kinopoisk". I also managed to collect data on over fifty actors, directors, screenwriters, cameramen, film composers, film critics, whose life was associated with Taganrog. -

Contemporary Latvian Theatre a Decade Bookazine

Edited by Lauma meLLēna-Bartkeviča Contemporary Latvian Theatre A Decade Bookazine PART OF LatVIAN CENTENARY PROGRAMME The publishing of the bookazine is supported by the Ministry of Culture and State Culture Capital Foundation. Preface ............................................................................................. 5 Lauma mellēna-Bartkeviča In collaboration with: TS THEATRE PROCESSES .................................................. 7 Theatre and Society: Socio-Political Processes and their EN Portrayal in Latvian Theatre of the 21st Century .................... 8 Zane radzobe T New Performance Spaces and Redefinition of the Relationship between Performers and Audience Members in 21st-Century Latvian Theatre: 2010–2020 ..... 24 ON valda čakare, ieva rodiņa idea and concept: Lauma Mellēna-Bartkeviča C editorial board: Valda Čakare (PhD), Lauma Mellēna-Bartkeviča (PhD), Latvian Theatre in the Digital Age .......................................... 36 Ieva Rodiņa (PhD), Guna Zeltiņa (PhD) vēsma Lēvalde reviewers: Ramunė Balevičiūtė (PhD), Anneli Saro (PhD), Newcomers in Latvian Theatre Directing: OF Edīte Tišheizere (PhD) the New Generation and Forms of Theatre-Making .......... 50 ieva rodiņa translators: Inta Ivanovska, Laine Kristberga E Proofreader: Amanda Zaeska Methods of Text Production in Latvian artist: Ieva Upmace Contemporary Theatre............................................................... 62 Photographs: credit by Latvian theatres and personal archives Līga ulberte Theatre Education in Latvia: Traditions and -

Urals Pathfinder: Theatre in Post-Soviet Yekaterinburg

URALS PATHFINDER: THEATRE IN POST-SOVIET YEKATERINBURG Blair A. Ruble KENNAN INSTITUTE OCCASIONAL PAPER # 307 The Kennan Institute is a division of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Through its programs of residential scholarships, meetings, and publications, the Institute encourages scholarship on the successor states to the Soviet Union, embracing a broad range of fi elds in the social sciences and humanities. The Kennan Institute is supported by contributions from foundations, corporations, individuals, and the United States Government. Kennan Institute Occasional Papers The Kennan Institute makes Occasional Papers available to all those interested. Occasional Papers are submitted by Kennan Institute scholars and visiting speakers. Copies of Occasional Papers and a list of papers currently available can be obtained free of charge by contacting: Occasional Papers Kennan Institute One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 (202) 691-4100 Occasional Papers published since 1999 are available on the Institute’s web site, www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan This Occasional Paper has been produced with the support of the George F. Kennan Fund.The Kennan Institute is most grateful for this support. The views expressed in Kennan Institute Occasional Papers are those of the authors. Cover photo (above): “Kolyada Theatre at Night, Turgenev Street, Ekaterinburg, Russia.” © 2010 Kolyada Theatre Cover photo (below): “Daytime View of Kolyada Theatre, Turgenev Street, Ekaterinburg, Russia.” © 2006 Kolyada Theatre © 2011 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org ISBN 1-933549-77-7 WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Jane Harman, President, Director, and CEO BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseph B. -

Creative Multilingualism ET

K OHL Creative Multilingualism ET AL . A Manifesto Creative EDITED BY KATRIN KOHL, RAJINDER DUDRAH, ANDREW GOSLER, SUZANNE GRAHAM, MARTIN MAIDEN, WEN-CHIN OUYANG AND MATTHEW REYNOLDS Multilingualism Mul� lingualism is integral to the human condi� on. Hinging on the concept of Crea� ve Mul� lingualism — the idea that language diversity and crea� vity are mutually enriching — this � mely and thought-provoking volume shows how the concept provides a matrix for experimenta� on with ideas, approaches and methods. C The book presents four years of joint research on mul� lingualism across REATIVE disciplines, from the humani� es through to the social and natural sciences. It is structured as a manifesto, comprising ten major statements which are unpacked through various case studies across ten chapters. They encompass M areas including the rich rela� onship between language diversity and diversity ULTILINGUALISM of iden� ty, thought and expression; the interac� on between language diversity and biodiversity; the ‘prisma� c’ unfolding of meaning in transla� on; the benefi ts of linguis� c crea� vity in a classroom-se� ng; and the ingenuity underpinning ‘conlangs’ (‘constructed languages’) designed to give imagined peoples a dis� nc� ve medium capable of expressing their cultural iden� ty. This book is a welcome contribu� on to the fi eld of modern languages, highligh� ng the intricate rela� onship between mul� lingualism and crea� vity, and, crucially, reaching beyond an Anglo-centric view of the world. Intended to spark further research and discussion, this book appeals to young people interested in languages, language learning and cultural exchange. It will be a valuable resource for academics, educators, policy makers and parents of bilingual or mul� lingual children. -

Urals Pathfinder: Theatre in Post-Soviet Yekaterinburg

URALS PATHFINDER: THEATRE IN POST-SOVIET YEKATERINBURG Blair A. Ruble KENNAN INSTITUTE OCCASIONAL PAPER # 307 The Kennan Institute is a division of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Through its programs of residential scholarships, meetings, and publications, the Institute encourages scholarship on the successor states to the Soviet Union, embracing a broad range of fi elds in the social sciences and humanities. The Kennan Institute is supported by contributions from foundations, corporations, individuals, and the United States Government. Kennan Institute Occasional Papers The Kennan Institute makes Occasional Papers available to all those interested. Occasional Papers are submitted by Kennan Institute scholars and visiting speakers. Copies of Occasional Papers and a list of papers currently available can be obtained free of charge by contacting: Occasional Papers Kennan Institute One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 (202) 691-4100 Occasional Papers published since 1999 are available on the Institute’s web site, www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan This Occasional Paper has been produced with the support of the George F. Kennan Fund.The Kennan Institute is most grateful for this support. The views expressed in Kennan Institute Occasional Papers are those of the authors. Cover photo (above): “Kolyada Theatre at Night, Turgenev Street, Ekaterinburg, Russia.” © 2010 Kolyada Theatre Cover photo (below): “Daytime View of Kolyada Theatre, Turgenev Street, Ekaterinburg, Russia.” © 2006 Kolyada Theatre © 2011 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org ISBN 1-933549-77-7 WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Jane Harman, President, Director, and CEO BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseph B. -

Crush / Korotkoe Zamykanie

CRUSH / KOROTKOE ZAMYKANIE Russia / 2009 / Drama, Romance / 95 min. / colour / feature film ANNOTATION “CRUSH” is an almanac about different manifestations of love. The five short stories represent a statement of new Russian filmmakers on the subject of love. The main characters – a shoemaker, a reporter, a promo-man, a mental hospital patient and a young ex-convict – are all “people of no importance”. They are the heroes of our time – of a time that knows no heroes. They all share one important feature: they are open-hearted and not afraid of love. Directors BORIS KHLEBNIKOV, IVAN VYRYPAEV , PYOTR BUSLOV, KIRILL SEREBRENNIKOV, ALEXEY GERMAN JR. Producer SABINA EREMEEVA “SHAME” Director BORIS KHLEBNIKOV Script MAXIM KUROCHKIN IVAN UGAROV BORIS KHLEBNIKOV Director of photography SHANDOR BERKESHI Production design OLGA KHLEBNIKOVA Costume design SVETLANA MIKHAILOVA Make-up RAISA MOLTCHANOVA Sound MAXIM BELOVOLOV Editing IVAN LEBEDEV Cast Sasha ALKSANDR YATSENKO Street guy ILYA SHERBININ Olya IRINA BUTANAEVA Husband EVGENI SYTYI Wife OLGA ONOSHCHENKO Activist lady EKATERINA KUZMINSKAYA Old lady EVGENIA AGENOROVA Older woman ALBINA TIKHONOVA Bull ALEXANDER KASHCHEEV “TO FEEL” Director IVAN VYRYPAEV Script IVAN VYRYPAEV Director of photography FEDOR LYASS Production and costume design MARGARITA ABLAEVA Make-up OLGA MIROSHNICHENKO Sound ROMAN KHOKHLOV Editing SERGEI IVANOV PAVEL KHANIUTIN Cast Gilr KAROLINA GRUSZKA Guy ALEXEY FILIMONOV “URGENT REPAIR” Director PYOTR BUSLOV Script ANDREI MAGACHEV PYOTR BUSLOV Director of photography IGOR GRINYAKIN -

Theatre Union of the Russian Federation

STRASTNOY BOULEVARD,10 SPECIAL ISSUE INTERNATIONAL AMAUTER THEATRE ASSOCIATION CONTENTS RECOGNITION AWARD OF The Territory of the Young THE RUSSIAN THEATRE UNION Actors’ Theatre CEC AITA General Assembly Setting the Bar High International Summer Theatre Theatre Meetings on the Yauza School–2019 The Neva Theatre Meetings International Theatre Project “Playing One Play” RUSSIAN THEATRES ABROAD «Theatre Revolution» in Tyumen Jyväskylä, the Town of Theatre Search of theatricality We Were Together “Vilnius Stage Lights. Children.” FESTIVALS IN RUSSIA The Jubilee Festival on Olkhon NEWS, ANNOUNCEMENTS «You are Invited on Stage» Actor Happiness 2020 THEATRE UNION OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION RUSSIAN THEATRE SOCIETY 2 RUSSIAN CENTRE OF INTERNATIONAL AMATEUR THEATRE ASSOCIATION (AITA/IATA) 10 Strastnoy Boulevard, RUS-107031 Moscow Phone / fax: +7 (495) 694 07 02 Compiled by Alla Zorina E-mail: Editor Natalia Staroselskaya [email protected] Translated by Tamara Arapova [email protected] Design by Lyudmila Sorokina STRASTNOY BOULEVARD, 10 SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 3 RECOGNITION AWARD 2019 The winners of the Recognition in the nomination “For the support Award established by the Russian of Russian amateur theatre”; Theatre Union are: Mirutenko Kira Sergeevna, art Ladysev Artur Valerievich, artistic manager and theatre director of the director of the “Children of Monday” Russian Studio Theatre “ART Master” in Studio Theatre, Sortavala, Republic of Jyvaskyla, Finland — in the nomination Karelia — in the nomination “For the “For maintaining traditions of contribution -

Plans for the National Theatre's Next Five Years

szcenárium MITEM English, April 2018 Plans for the National Theatre’s Next Five Years ATTILA VIDNYÁNSZKY National Theatres in Smaller European Countries STEPHEN WILMER MITEM Retrospective 2014–2017 ZSOLT SZÁSZ – ÁGNES PÁLFI Articles by/about this Year’s Guests ROLF C. HEMKE, MOHAMED MOUMEM, FADHEL JAÏBI, PARVATHY BAUL, ANTONIO LATELLA – ANDREA BAJANI A Nemzeti Színház művészeti folyóirata authors Albert, Dénes (1962) journalist, translator Bajani, Andrea (1975) writer, journalist Baul, Parvathy (1976) singer, artist, storyteller Durkóné Varga, Nóra (1965) translator, English teacher Hemke, Rolf C. (1972) dramaturge for public relations and marketing at Theater an der Ruhr, artistic director of Kunstfest Weimar Kocsis, Anikó (1969) translator, English teacher Latella, Antonio (1967) stage director Moumen, Mohamed, theatre aesthete and reviewer Pálfi , Ágnes (1952) poet, essayist, editor of Szcenárium Regéczi, Ildikó (1969) reader at Institute of Slavic Studies, University of Debrecen Szász, Zsolt (1959) puppeteer, dramaturge, stage director, managing editor of Szcenárium Vidnyánszky, Attila (1964) stage director, general manager of the National Theatre in Budapest Wilmer, Stephen (1944) Fellow Emeritus at Trinity College, Dublin Támogatók PUBLISHER IN-CHIEF: Attila Vidnyánszky • EDITOR IN-CHIEF: Zsolt Szász • EDITOR: Ágnes Pálfi • LAYOUT EDITOR: Bence Szondi • MAKER-UP: Nyolc és fél Bt. • SECRETARY: Noémi Nagy • EDITORIAL STAFF: Nina Király (theatre historian, world theatre, international relations), Ernő Verebes (author, composer, dramaturge),