Constructive Men's Engagement (Cme) in Enhancing Reproductive Health in Makindu and Mutitu Sub-Counties of Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mbeere District Short Rains Assessment Report

MBEERE DISTRICT SHORT RAINS ASSESSMENT REPORT 15TH – 18TH FEBRUARY 2008 Assessment Team Eliud Wamwangi Ministry of Water and Irrigation Lydia Macharia Ministry of Health Julius Kisingu World Food Programme TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 1.1 District Backgroud Information.................................................................................1 1.2 History of Relief Operations......................................................................................1 1.3 Food Security Trends.................................................................................................1 1.4 Summary of Recommendations.................................................................................1 2 DISTRICT FOOD SECURITY SITUATION...................................................................2 2.1 Overall Food Security Situation.................................................................................2 2.2 Impact of Shocks and Harzards on Food Security.....................................................3 2.2.1 Rainfall...............................................................................................................3 2.2.2 Crop Production and Prices ...............................................................................4 2.2.3 Livestock Production and Prices........................................................................7 2.2.4 Water and Sanitation..........................................................................................8 -

Explaining Resource Use, Management and Productivity Among the Akamba, Orma and Somali in the Former Eastern Statelands of Kenya

©Kamla-Raj 2004 Stud. Tribes Tribals, 2(1): 55-63 (2004) Common Range, Different Tribes: Explaining Resource Use, Management and Productivity among the Akamba, Orma and Somali in the former Eastern Statelands of Kenya Dickson Mong’are Nyariki1 and Jan Van den Abeele2 1. Department of Range Management, University of Nairobi P.O. Box 29053, Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] 2. Forestry Development Support Programme, Belgian Technical Cooperation, P.O. Box 30513, Nairobi, Kenya KEYWORDS Common use; range management; resource conflicts; Eastern Statelands; Kenya ABSTRACT This paper describes the major livelihood activities of three ethnic communities who use in common the former Kenyan Eastern Statelands. It also looks at how the livelihoods and the range could be improved while maintaining the common access to resources, so as to avoid potential conflicts. It is suggested that for improvement of range management the unsettled lands should be accessed by all the communities under ranching societies without having to exclude non-members. A number of approaches should be instituted, including bush control and reseeding. Bush control can be achieved through exploitation of trees of low timber value for charcoal production to earn income for households. To increase livestock productivity, it is proposed that proper livestock and grazing management be practised, including the introduction of superior breeds, improved livestock facilities, adequate animal healthcare and rotational grazing through paddocking. INTRODUCTION and improve the living standards of the communities, the stakeholders and development The colonial government in Kenya set aside agents should rethink the use and management the former Eastern Statelands for State of this resource. -

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers OVERVIEW OF FOREST PESTS KENYA January 2007 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/20E Forest Management Division FAO, Rome, Italy Forestry Department DISCLAIMER The aim of this document is to give an overview of the forest pest1 situation in Kenya. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © FAO 2007 1 Pest: Any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products (FAO, 2004). Overview of forest pests - Kenya TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Forest pests...................................................................................................................... 1 Naturally regenerating forests..................................................................................... 1 Insects ..................................................................................................................... 1 Diseases.................................................................................................................. -

10.18697/Ajfand.75.ILRI03 10991 10.18697/Ajfand.75.ILRI03

10.18697/ajfand.75.ILRI03 AFLATOXIN B1 OCCURRENCE IN MILLET, SORGHUM AND MAIZE FROM FOUR AGRO-ECOLOGICAL ZONES IN KENYA Sirma AJ1, 2*, Senerwa DM1, 2, Grace D1, Makita K1, 3, Mtimet N1, Kang’ethe EK2 and JF Lindahl1, 4 *Corresponding author email: [email protected] 1International Livestock Research Institute, P.O. Box 30709-00100, Nairobi, Kenya 2University of Nairobi, P.O. Box 29053-00625, Nairobi, Kenya 3Rakuno Gakuen University, 582 Bunkyodai Midorimachi, Ebetsu, 069-8501, Japan 4Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 7054, SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden 10.18697/ajfand.75.ILRI03 10991 ABSTRACT Aflatoxin-contaminated food is a public health concern. Contamination of staple foods in Kenya has in the past led to loss of human lives as well as condemnation of large quantities of food, contributing to food insecurity. This study investigated the occurrence of aflatoxins in maize, millet and sorghum from five counties in Kenya (Kwale, Isiolo, Tharaka-Nithi, Kisii and Bungoma) representing four agro-ecological zones (AEZs). Samples were collected from rural households in two phases between February and October 2014. Using competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), 497 maize, 205 millet and 164 sorghum samples were screened for the presence of aflatoxin B1. Overall, 76% of maize, 64% of millet and 60% of sorghum samples were positive for aflatoxin B1. Of these, the proportion of samples with aflatoxin B1 levels above the Kenya Bureau of Standards limit of five parts per billion was 26% for maize, 10% for millet and 11% for sorghum. In samples collected during the second phase, there were significant differences in the mean levels of aflatoxin contamination between the agro- ecological zones (p<0.05); maize from Kisii and Bungoma, representing temperate AEZ, had the lowest mean contamination, whereas millet and sorghum from Tharaka-Nithi (humid) and Isiolo (semi-arid), respectively, had the highest mean contamination. -

Factors Influencing Household Income in Unbound Project, Chiakariga County Assembly Ward, Tharaka-Nithi County, Kenya

FACTORS INFLUENCING HOUSEHOLD INCOME IN UNBOUND PROJECT, CHIAKARIGA COUNTY ASSEMBLY WARD, THARAKA-NITHI COUNTY, KENYA BY MARIUS MARY WANJIKU A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PROJECT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI JUNE 2017 DECLARATION This thesis contains my original work and has not been presented for a degree or any other award in any other university. Signature………………… Mary Wanjiku Marius Date……………………… L50/73360/2014 This thesis has been submitted with my approval as the University Supervisor Signature…………………… Prof. Nathan Gichuki Date……………………. Associate Professor School of Biological Sciences, University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my daughter Mitchelle Muthoni for her support and sacrifice as I was out of home most of the time and she understood and persevered. I also dedicate it to my late father Marius Njeru, who sacrificed his comfort to educate and teach me the value of education. It is also dedicated to my mother Nancy Mutitu, who has always encouraged and supported me throughout my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Sincere gratitude is extended to the following for their dedication and increasing support until the proposal was fully structured. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Nathan Gichuki, who tirelessly guided me throughout my research from the conceptualization of the research project, its execution and write up of the thesis. My supervisor taught me to be patient, strong and rigorous. Secondly, I wish to thank Mr. Amos Gitonga of the University of Nairobi’s Meru Extra Mural Center, and all the lecturers who taught me tirelessly and were always patient with me. -

Aprp 2011/2012 Fy

KENYA ROADS BOARD ANNUAL PUBLIC ROADS PROGRAMME FY 2011/ 2012 Kenya Roads Board (KRB) is a State Corporation established under the Kenya Roads Board Act, 1999. Its mandate is to oversee the road network in Kenya and coordinate its development, rehabilitation and maintenance funded by the KRB Fund and to advise the Minister for Roads on all matters related thereto. Our Vision An Effective road network through the best managed fund Our Mission Our mission is to fund and oversee road maintenance, rehabilitation and development through prudent sourcing and utilisation of resources KRB FUND KRB Fund comprises of the Road Maintenance Levy, Transit Toll and Agricultural cess. Fuel levy was established in 1993 by the Road Maintenance Levy Act. Fuel levy is charged at the rate of Kshs 9 per litre of petrol and diesel. The allocation as per the Kenya Roads Board Act is as follows: % Allocation Roads Funded Agency 40% Class A, B and C KENHA 22% Constituency Roads KERRA 10% Critical links – rural roads KERRA 15% Urban Roads KURA 1% National parks/reserves Kenya Wildlife Service 2% Administration Kenya Roads Board 10% Roads under Road Sector Investment Programme KRB/Minister for Roads KENYA ROADS BOARD FOREWORD This Annual Public Roads Programme (APRP) for the Financial Year (FY) 2011/2012 continues to reflect the modest economic growth in the country and consequently minimal growth in KRBF. The Government developed and adopted Vision 2030 which identifies infrastructure as a key enabler for achievement of its objective of making Kenya a middle income country by 2030. The APRP seeks to meet the objectives of Vision 2030 through prudent fund management and provision of an optimal improvement of the road network conditions using timely and technically sound intervention programmes. -

USAID Kenya Nutrition and Health Program Plus QUARTER FY Progress Report

USAID Kenya Nutrition and Health Program plus QUARTER FY Progress Report USAID KENYA Nutrition and Health Program plus QUARTER 1 FY 2015/2016 PROGRESS REPORT 01 October l – 31 December 2015 Award No: AID-615-H-15-00001 Prepared for Ruth Tiampati United States Agency for International Development/Kenya C/O American Embassy United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 629, Village Market 00621 Nairobi, Kenya Prepared by: Nutrition and Health Program plus 2nd Floor Chancery Building, Valley Road P.O Box 38835 00623 Nairobi, Kenya The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. i Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. III I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 5 II. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS (QUALITATIVE IMPACT) ......................................................... 8 1. IMPROVING ACCESS AND DEMAND FOR QUALITY NUTRITION INTERVENTIONS AT COMMUNITY AND FACILITY LEVELS ........................................................................... 8 1.1 Strengthening Leadership, Advocacy and Policy Planning ............................................... 8 1.2 Improving Nutrition Service Delivery Management, Coordination and Implementation .... 9 1.3 Improving Nutrition Related Behaviour ............................................................................. 9 1.4 Increasing -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Boniface Mwanzia Kavoi (BVM, PGDE, MSc, PhD) 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION Names: Dr Boniface Mwanzia Kavoi; Date of Birth: April 18, 1972; Nationality: Kenyan; Marital status: Married; Confession: Protestant; Languages: English, Kiswahili; Tel., + 254 02 4446764 Ext 2336 Mobile: +254 720895968 E-mail: [email protected] Contact address: C/o Department of Veterinary Anatomy & Physiology, Chiromo Campus, University of Nairobi, P.O Box 30197-00100, Nairobi. 2. SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS After graduating with a Bachelors degree in Veterinary Medicine from the University of Nairobi in November 1998, I registered with the Kenya Veterinary Board and began private clinical practice in Machakos and Makueni Counties in Kenya. At the same time, I served as a teacher (Chemistry & Biology) in Masii S.D.A Secondary School in Machakos County. In 2001, I was employed by Choicemeds Pharmaceutical Company as a Medical Representative, a position I 2 held until 2003 when I left to join Mutitu S.D.A Secondary School (Makueni County) as a Science teacher and a Dairy Farm Manager. While working as a teacher in Mutitu S.D.A, I registered for a school-based postgraduate training in education at Egerton University. After completing the teacher training in 2004, I was employed by the University of Nairobi as a Tutorial Fellow in the Department of Veterinary Anatomy and Physiology. My MSc program, which I started immediately after joining the department, was completed in November 2008. My PhD work was started in 2009 and was successfully completed in October 2012. My earlier and current research (theses and publications) mainly focuses on smelling and the smelling tissue in the nasal cavity and the brain of vertebrates. -

Interruption of Electricity Supply

ELGEYO MARAKWET COUNTY Interruption of AREA: EMSEA, BIRETWO DATE: Thursday 21.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. Emsea, Chegilet, Biretwo, Kebulwo, Muskut, Cheptebo, Sego & Electricity Supply adjacent customers. Notice is hereby given under rule 27 of the Electric Power Rules That the electricity supply will be interrupted as here under: WESTERN REGION (It is necessary to interrupt supply periodically in order to facilitate maintenance and upgrade of power lines to the network; to connect new customers or to replace power lines during road SIAYA COUNTY construction, etc.) AREA: MUR MALANGA MKT, TINGWANGI, ANDURO DATE: Saturday 16.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 3.00 P.M. Anduro Pri Sch, Randago, Nyanginja Youth Polytechnic, Matera Sec Sch, Rakuom Pri Sch, Mur Malanga Mkt, Ambrose Adeya Sec Sch, Mugane Pri NAIROBI NORTH REGION Sch, Tingwangi Airtel Booster, Sulwe Estate & adjacent customers. NAIROBI COUNTY VIHIGA COUNTY AREA: GIKOMBA FEEDER AREA: KIMA MKT, EMUSIRE, EMUHAYA DATE: Sunday 17.05.2020 TIME: 8.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. DATE: Monday 18.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 11.00 A.M. Nacico Plaza, Machakos Country Bus, Kenya Cold Storage, KMC, Equity Maseno Water, Mwichio Mkt, Kima Mission, Kima Mkt, Esikulu Mkt, Ematioli, Bank, COTU, Pumwani Rd, Kombo Munri Rd, Ismailia Flats, Digo Rd, Kariako Emanyinya, Emusire H/c, Esunza, Emuhaya H/c, Emuhaya CC Ofice, Ibubi, Flats, Ziwani Est, Habib, Starehe DO Offices, Gikomba Mkt, Starehe Boys, Wemilabi Safaricom Booster, Maseno Coptic Hosp, Ebusakami & adjacent Quarry Rd, Whole of Kariako, Gikomba & adjacent customers. customers. AREA: MUHUDU MKT, SHIANDA VILLAGE, MUYELE NAIROBI WEST REGION DATE: Tuesday 19.05.2020 TIME: 8.30 A.M. -

The Scourge of Aflatoxins in Kenya: a 60-Year Review (1960 to 2020)

Hindawi Journal of Food Quality Volume 2021, Article ID 8899839, 31 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8899839 Review Article The Scourge of Aflatoxins in Kenya: A 60-Year Review (1960 to 2020) Timothy Omara ,1,2,3 Ambrose K Kiprop ,1,2 Phanice Wangila,4 Alex Paul Wacoo ,5 Sarah Kagoya ,6 Papias Nteziyaremye ,1,2 Mark Peter Odero ,1,2 Caroline Kiwanuka Nakiguli ,1,2,7 and Samuel Baker Obakiro 1,2,8 1Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, School of Sciences and Aerospace Studies, Moi University, Uasin Gishu County, P.O. Box 3900, Eldoret, Kenya 2Africa Center of Excellence II in Phytochemicals, Textiles and Renewable Energy (ACE II PTRE), Moi University, Uasin Gishu County, P.O. Box 3900, Eldoret, Kenya 3Department of Quality Control and Quality Assurance, Product Development Directory, AgroWays Uganda Limited, Plot 34-60, Kyabazinga Way, P.O. Box 1924, Jinja, Uganda 4Department of Physical Sciences, University of Kabianga, P.O. Box 2030, Kericho, Kenya 5Department of Medical Biochemistry, School of Biomedical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, P. O. Box 7026, Kampala, Uganda 6Department of Quality Control and Quality Assurance, Sweets and Confectionaries Section, Kakira Sugar Limited, P.O. Box 121, Jinja, Uganda 7Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, P.O. Box 1410, Mbarara, Uganda 8Department of Pharmacology and >erapeutics, Faculty of Health Sciences, Busitema University, P.O. Box 1460, Mbale, Uganda Correspondence should be addressed to Timothy Omara; [email protected] Received 30 May 2020; Revised 4 September 2020; Accepted 3 February 2021; Published 18 February 2021 Academic Editor: Luis Patarata Copyright © 2021 Timothy Omara et al. -

Mapping and Characterising Water Points in Mbeti South Location, Mbeere District

MAPPING AND CHARACTERISING WATER POINTS IN MBETI SOUTH LOCATION, MBEERE DISTRICT IEA Research Paper Series No. 21 April 2009 Published by: INSTITUTE OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 5th Floor, ACK Garden House 1st Ngong Avenue P.O. Box 53989 Nairobi- 00200 Tel: 254-20-2717402, 2721262 Fax: 254-20-2716231 Email: [email protected] Written by: Zacchaeus Kinuthia, David Warui and Francis Karanja of Centre for Training & Integrated Research in ASAL Development (CETRAD) P.O. Box 144 Nanyuki 10400 Tel: 062-31328; Fax: 062-31323 E-mail: [email protected] With the support of Heinrich Boll Foundation (HBF) Institute of Economic Affairs, 2009 First Published in 2009 ISBN: 978-9966-7183-8-9 Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Table of Content Acknowledgement .......................................................................................................................7 Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................8 Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................................................12 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................13 1.1. Water resources in Kenya: An overview .........................................................................13 1.2. The Tana River Drainage Basin ......................................................................................15 1.3. Mbeere District ..............................................................................................................15 -

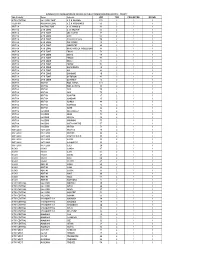

Sub-County Zone Schools LDD TDD PROJECTOR DCSWR KITUI

SUMMARY OF INSTALLATION OF DEVICES IN PUBLIC PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN KITUI COUNTY Sub-County Zone Schools LDD TDD PROJECTOR DCSWR KITUI CENTRAL KALUNDU ZONE A.C.K KAVOKO 172 2 1 1 TSEIKURU MUSAVANI ZONE A.C.K NGOMANGO 53 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIK0 ZONE A.I.C MAKOLO 63 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE A.I.C NGUUNI 55 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE ABC KASEVI 37 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE ATHI 55 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE Central Primary 50 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE CIAITUNGU 42 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE CIOKEREKE 48 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE DAVID MUSILA (NDELEKENI) 66 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE EKANI 56 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE EMIVIA 50 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE ENDAU 56 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE ENZIU 45 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE ENZOU 51 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE GACIGONGO 48 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE GAI 46 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE GAKOMBE 40 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE GATORONI 42 2 1 1 IKUTHA ATHI ZONE GATUNDU 42 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA HON. KIEMA 111 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA HON.MUTISYA 96 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IIANI 58 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IIANI 75 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IKAAYUNI 37 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IKANDANI 45 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IKANGA 48 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IKATHIMA 42 2 1 1 IKUTHA IKUTHA IKAVE 42 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIKO IKILUNGULU 76 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIKO IKIME 71 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIKO IKISAYA 68 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIKO IKOONGO 55 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIKO IKOTA MWITHE 57 2 1 1 IKUTHA KANZIKO IKUTHA 71 2 1 1 KATULANI KATULANI IKUUSYA 48 2 1 1 KATULANI KATULANI IKUYUNI 42 2 1 1 KATULANI KATULANI IKYATINE D.E.B 33 2 1 1 KATULANI KATULANI ILAANI 33 2 1 1 KATULANI KATULANI ILALAMBYU 32 2 1 1 KATULANI KATULANI ILALU 20 2 1