The Kindness of Strangers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lovely Serendipitous Experience of the Bookshop’: a Study of UK Bookselling Practices (1997-2014)

‘The Lovely Serendipitous Experience of the Bookshop’: A Study of UK Bookselling Practices (1997-2014). Scene from Black Books, ‘Elephants and Hens’, Series 3, Episode 2 Chantal Harding, S1399926 Book and Digital Media Studies Masters Thesis, University of Leiden Fleur Praal, MA & Prof. Dr. Adriaan van der Weel 28 July 2014 Word Count: 19,300 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: There is Value in the Model ......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter Two: Change and the Bookshop .......................................................................................................... 17 Chapter Three: From Standardised to Customised ....................................................................................... 28 Chapter Four: The Community and Convergence .......................................................................................... 44 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................................... 51 Bibliography: ............................................................................................................................................................... 54 Archival and Primary Sources: ....................................................................................................................... -

The Images Speak for Themselves? Reading Refugee Coffee-Table Books

Visual Studies, Vol. 21, No. 1, April 2006 The images speak for themselves? Reading refugee coffee-table books ANNA SZO¨ RE´NYI The practice of collecting photographs of refugees in ‘coffee- consuming images. This article is concerned with the table books’ is a practice of framing and thus inflecting the implications of such texts and of the statements, such as meanings of those images. The ‘refugee coffee-table books’ Kumin’s, by which they are framed. What, indeed, are discussed here each approach their topic with a particular the effects of portraying refugees through photography? style and emphasis. Nonetheless, while some individual And in what sense can these effects be understood as images offer productive readings which challenge messages from refugees ‘themselves’? If these images stereotypes of refugees, the format of the collections and the speak, on whose behalf do they speak and what do they accompanying written text work to produce spectacle say? rather than empathy in that they implicitly propagate a According to the attitude expressed by Kumin, world view divided along imperialist lines, in which the photographs have an immediacy and intimacy that audience is expected to occupy the position of privileged engages the viewer. In the worldwide project of arousing viewing agent while refugees are positioned as viewed sympathy for refugees, such photographs seem to offer a objects. field for the development and expression of empathy. They draw on the tradition of socially concerned To suffer is one thing; another thing is living photography which has sought to provide a factual with the photographed images of suffering. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Beauty Knows No Borders

Beauty Knows No Borders Banff National Park Alberta, Canada Beauty Knows No Borders Banff National Park Alberta, Canada Available Sizes: 16x20, 20x24, 30x40, 40x50, 50x62 Artist’s Choice: Della Terra, Charcoal with Black Linen Artist Proof: 50 / Limited Edition: 500 Beauty Knows No Borders Field Notes Banff National Park Alberta, Canada Camera: Arca Swiss 8x10 F-Line Camera Lens: 150mm This past summer I had the great pleasure of spending it entirely with my son. Aperture: f45.3 Toward the end of our time together we drove from our home in Oregon all the way Exposure: 1/4 Second up to Alaska on the Can-Am (Canadian-American) highway. After a week long back Film: Professional Fuji Astia 100f country stint in Denali I put him on the redeye flight home as school started the next morning. I wouldn’t trade our time together for anything - it was a blast. On the drive back home from Alaska I took my time going through Canada. I wasn’t in my home country anymore, I was the foreigner and I was about to have an epiphany. There are amazing nature sights to behold there - everywhere. The first snowfall of the season had just dusted the mountains. I starred in awe as the clouds parted and a beam of light touched the surface of this stunning mountain lake and illuminated the entire valley. Man’s pitiful attempt to place arbitrary lines upon the surface of the earth to retain what they believe to be ‘theirs’, and call them “borders”, yields because beauty knows nothing about that, beauty knows no borders. -

Spring Design/Borders—2 Books As Well As Other Educational and Entertainment Items

NEWS RELEASE Spring Design and Borders Announce eBook Agreement Borders to be eBook Seller for Alex eReader FREMONT, Calif./ANN ARBOR, Mich. – January 7, 2010 – Spring Design and Borders Group, Inc. (NYSE: BGP) today announced an agreement in principle to feature the upcoming Borders eBook store powered by Kobo on the new dual display Alex™ eReader later this year. The agreement in principle follows a recent announcement that Borders will launch a new eBook store on Borders.com as well as Borders- branded mobile eBook applications, powered by Kobo. The new Borders-branded eBook store will offer more than two million titles. “The combination of Borders’ leadership in the book industry and Spring Design’s innovation and experience in consumer electronics will create a world class service for eBook readers,” said Dr. Priscilla Lu, chief executive officer of Spring Design. “This partnership delivers one of the critical foundations of our business growth going forward,” Lu added. “Our agreement with Spring Design represents another step in our digital strategy, which continues to focus on offering book lovers—including our more than 35 million Borders Rewards loyalty program members—high quality content on the device of their choosing,” said Borders Group Chief Executive Officer Ron Marshall. “We look forward to bringing a world class eBook experience to Alex users.” The Alex eReader will initially be available February 22, 2010 for $359 in the online store at www.springdesign.com. About Spring Design: Spring Design Inc., founded in 2006, designs and delivers eReader products to the e-book market. Its Alex is the first eBook with full function browser on Android with dual screen, interactive multi-media eReader. -

How Do Literary Works Cross Borders (Or Not)? a Sociological Approach to World Literature

Journal of World Literature 1 (2016) 81–96 brill.com/jwl How Do Literary Works Cross Borders (or Not)? A Sociological Approach to World Literature Gisèle Sapiro cnrs and École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected] Abstract This paper analyzes the factors that trigger or hinder the circulation of literary works beyond their geographic and cultural borders, i.e. participating in the mechanisms of the production of World Literature. For the sake of analysis, these factors can be clas- sified into four categories: political (or more broadly ideological), economic, cultural and social. Being embodied by institutions and by individual agents, these factors can support or contradict one another, thus causing tensions and struggles. This paper ends with reflections on the two opposite tendencies that characterize the transnational lit- erary field: isomorphism and the differentiation logics. Keywords World Literature – sociology of literature – sociology of translation – international circulation of literature – field theory If we consider world literature as referring to those literary works that circulate beyond their national borders (Damrosch), then we have to ask how these works circulate, and what obstacles they encounter (Apter). These obstacles are not only linguistic; there are many social obstacles, just as there are social factors that trigger the circulation of texts regardless of their intrinsic value. A sociological approach is thus required in order to identify these factors and the mechanisms of production of World Literature as well as its specific hierarchies (Casanova). In a seminal paper on “[t]he social conditions of the circulation of ideas,” Pierre Bourdieu outlined a program for studying the strategies elaborated by individuals or groups implied in this process (Bourdieu “Social Conditions”). -

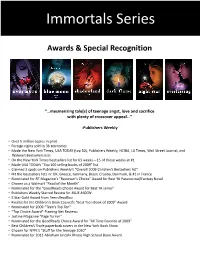

Immortals-Series-Fas

Immortals Series Awards & Special Recognition “…mesmerizing tale[s] of teenage angst, love and sacrifice with plenty of crossover appeal…” -Publishers Weekly • Over 5 million copies in print • Foreign rights sold to 36 territories • Made the New York Times, USA TODAY (top 50), Publishers Weekly, NCIBA, LA Times, Wall Street Journal, and Walmart Bestsellers lists • On the New York Times bestsellers list for 63 weeks—15 of those weeks at #1 • Made USA TODAYs “Top 100 selling books of 2009” list • Claimed 3 spots on Publishers Weekly’s “Overall 2009 Children’s Bestsellers list” • Hit the bestsellers lists in: UK, Greece, Germany, Brazil, Croatia, Denmark, & #1 in France • Nominated for RT Magazine's "Reviewer's Choice" Award for Best YA Paranormal/Fantasy Novel • Chosen as a Walmart “Read of the Month” • Nominated for the “GoodReads Choice Award for Best YA series” • Publishers Weekly Starred Review for BLUE MOON • 5 Star Gold Award from TeensReadToo • Finalist for the Children's Book Council's "Best Teen Book of 2009" Award • Nominated for 2009 “Teen's Top Ten” • “Top Choice Award”-Flaming Net Reviews • Justine Magazine “Page Turner” • Nominated for the GoodReads Choice Award for "All Time Favorite of 2009” • Best Children’s Trade paperback covers in the New York Book Show • Chosen for NYPL's "Stuff for the Teenage 2010“ • Nominated for 2011 Abraham Lincoln Illinois High School Book Award Evermore #1 New York Times Bestseller USA TODAY Bestseller International Bestseller Borders Bestseller Amazon Bestseller St. Martin's Griffin, February -

Digital Publishing Without Borders

Exporting English: Digital Publishing Without Borders Manage Transform Publish Contents 1. The Global Publishing Market – Exporting English 2. Digital Rights: To Sell or To Hold? 3. English Content in Non-English Speaking Territories Global Book Publishing $151 Billion International Publishers Association 2013 Growth of U.S. Exports of English Language Books • U.S. 2012 reported net revenue from export of books = $833 million or approximately 3% of overall net revenue ($27B) and 7.2% gain over previous year • eBooks made up 20% of overall net revenues or $166 million • eBook net revenue from exports grew 63% in 2011 Source: 2013 AAP Export Sales Report/ BISG’s BookStats 2013 To Distribute or To Sell Territory Rights: That is the Question? Who’s Selling Digital Rights at the Territory Level? • If you own the digital rights use them! • No printing, no shipping • Plenty of global outlets for distribution • Translation may not even be an issue st Capital in the 21 Century eBook • Sold more than 50,000 copies in the original French hardcover edition • Harvard Press sold more than 80,000 hardcover copies in US as of May 2014 • eBook edition hit #1 at Amazon in April; approximately 30,000 copies sold at $16.26 • Nook eBook $21.99 • Kobo International €21.77 Potential for English Language Digital Content nd Populations of English as 2 Language China France 300 Million 25 Million India Italy 225 Million 20 Million Pakistan Brazil 92 Million 16 Million Philippines Netherlands 52 million 15 million Germany Poland 51 Million 13 Million Bangaldesh -

Terms of Reference Photography And

TERMS OF REFERENCE PHOTOGRAPHY AND PRODUCTION OF A COFFEE TABLE BOOK ON THE MULTIVERSE OF WOMEN IN THE IGAD REGION Background Land governance across borders or transnational land governance looks at rule making, standard setting and institution building across borders. Empirically, one can see a variety of patterns of regulatory governance emerging. The studies commissioned by IGAD in 2016 reviewing the of land governance systems in the IGAD Member States identified four transnational elements: state sovereignty over land; legal pluralism (customary and statutory); gender biases in access to land; land tenure insecurity and land conflicts. In the IGAD Region, national organisation as a structuring principle of societal and political action can no longer serve as the orienting reference point. This creates the need for increased cooperation among nations. The IGAD region finds itself in a time where economic, social and political developments in one country are increasingly affected by developments in others; and where opportunities and threats to people are no longer exclusively the responsibility of individual governments; The transnational sphere of land governance in the IGAD region is built neither upon nor beyond national institutional frameworks (full integration). Rather, the transnational sphere of land governance in the IGAD region transcends national borders while at the same time being entangled in historically contingent institutions and shaped by actors rooted in locally and nationally diverse contexts (Convergence). In dealing with cross border contexts in land governance, it is important to understand how transnational rules are implemented on the ground, how they are monitored by civil and public actors, and whether there is any learning from local experiences going on, or not. -

Managing Intellectual Property in the Book Publishing Industry a Business-Oriented Information Booklet

Managing Intellectual Property in the Book Publishing Industry A business-oriented information booklet Creative industries – Booklet No. 1 Managing Intellectual Property in the Book Publishing Industry A business-oriented information booklet Creative industries – Booklet No. 1 Managing Intellectual Property in the Book Publishing Industry Managing Intellectual Property in the Book Publishing Industry 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 5 INTRODUCTION 7 SECTION A 11 Basic Notions of Copyright and other Relevant Rights in the Book Publishing Industry 11 Copyright 12 What is copyright? 12 What rights does copyright provide? 14 Who owns copyright? 15 How long does copyright last? 16 Are some works free of copyright? 16 Does copyright protect titles, names and characters? 19 Trademarks 24 Confidential Information and Trade Secrets 28 Further Business and Legal Considerations 28 SECTION B 30 The Book Publishing Value Chain 30 Publishing Across the Digital Landscape 36 SECTION C 38 Publishers’ Responsibilities in Negotiating Agreements 38 C.i. Managing Primary Rights 39 Grant of rights and specification 39 Commissioned works 40 Delivery and publication dates 41 Acceptability 42 Warranties and indemnities 43 Payments to authors and other creators 43 Other publisher issues 45 Termination 45 Concluding an agreement 46 Managing Intellectual Property in the Book Publishing Industry 4 C.ii. Managing Secondary and Third-Party Rights 47 Operating a secure permissions system 47 Text excerpts 48 Illustrations and web content 50 Drawn artwork 50 Photographs 51 Fine art 52 Picture acknowledgements 52 Web content 52 Conclusion 53 C.iii. Managing Subsidiary Rights 53 SECTION D 58 The Collective Administration of Rights 58 SECTION E 62 Business Models: Payment to Authors, Permissions and Subsidary Rights 62 E.i . -

Robert Darnton, “What Is the History of Books?”

What is the History of Books? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darnton, Robert. 1982. What is the history of books? Daedalus 111(3): 65-83. Published Version http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024803 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3403038 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ROBERT DARNTON What Is the History of Books? "Histoire du livre" in France, "Geschichte des Buchwesens" in Germany, "history of books" or "of the book" in English-speaking countries?its name varies from to as an new place place, but everywhere it is being recognized important even discipline. It might be called the social and cultural history of communica were not a to tion by print, if that such mouthful, because its purpose is were understand how ideas transmitted through print and how exposure to the printed word affected the thought and behavior of mankind during the last five hundred years. Some book historians pursue their subject deep into the period on before the invention of movable type. Some students of printing concentrate newspapers, broadsides, and other forms besides the book. The field can be most concerns extended and expanded inmany ways; but for the part, it books an area so since the time of Gutenberg, of research that has developed rapidly seems to a during the last few years, that it likely win place alongside fields like art canon the history of science and the history of in the of scholarly disciplines. -

Classic Borders Stencils Ebook Free Download

CLASSIC BORDERS STENCILS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julie Collins-Rousseau | 32 pages | 01 Jul 1999 | MURDOCH BOOKS | 9781853916960 | English | London, United Kingdom Classic Borders Stencils PDF Book CafePress brings your passions to life with the perfect item for every occasion. ShapeSource by Visimation is your one-stop source for Visio stencils , Visio shapes and Visio templates. Damask Wallpaper is a great bedroom wallpapers to create an elegant look, or dining room to achieve a very rich atmosphere. If the material that has accumulated on top of the stencil flakes off, then the stencil is ready to come up. Please enter five or nine numbers for the postcode. I thought it was simply an update. Print them off and follow the easy instructions below on. Step 2: Prepare the Stencil Remove the stencil from its shipping container and place it on a flat surface in a warm place, like the kitchen. Browse our offerings. Hi, I'm Jessica! If you are stenciling with a paint brush, avoid brushing paint onto the stencil and instead apply color by stippling with the brush or swirling the brush in small, circular motions. The top and bottom edges of the wall is another place you might not have room for a full repeat of the stencil pattern. Using the projector, display your image on the brick wall and trace the edges with a chalk marker. This product has been discontinued. Custom stencils, painting and decorating stencils and free illustrated stencil Bring the beautiful outdoors inside with a botanical stencil. It is 21 days later now. Free Store Pickup.