THE BETH DIN: Jewish Law in the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

FIRST TIME MAKING PESACH a Cheat Sheet for the Rest of Us

Rabbi Dovid Cohen Administrative Rabbinic Coordinator, cRc FIRST TIME MAKING PESACH A cheat sheet for the rest of us Preparing for Pesach takes effort, but with a bit of planning and focus it is possible to succeed and welcome Yom Tov positively. This article’s goal is not to provide details and instructions, but rather to provide a framework of what must be done and issues to consider, and guidance on how to learn more about those topics. The “Tell Me More” sidebars reference articles in the cRc 2021 Pesach Guide where more information is available on a given topic. This article is written specifically for those who have never made Pesach at home or have not done so for many years, but also may be a good overview for those who have more experience. A) SCHEDULE if we will be home on Pesach, then we must also clean our houses to ensure we do not accidentally eat any chametz on Finding ways to be organized and scheduled goes a long Pesach. We identify all chametz, and either destroy it or put it way towards having a successful preparatory Pesach season. into a closet, cabinet, or room that will be closed for Yom Tov Many find it helpful to work backwards, thinking which jobs and sold to a non-Jew.1 should or must happen on Erev Pesach, which in the days before that, etc. so that they roughly plan when each item Which foods are chametz and must be removed? The will get taken care of. letter of the law is that only items which meet these three requirements must be removed: In this context it is worth noting that many Pesach tasks can be performed well in advance of Yom Tov. -

Getting Your Get At

Getting your Get at www.gettingyourget.co.uk Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers. by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB The website at www.gettingyourget.co.uk is sponsored by Barnett Alexander Conway Ingram, Solicitors, London 1 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Dedicated to the loving memory of Sharon Faith’s late parents, Maisie and Dr Oswald Ross (zl) and Deanna Levine’s late parents, Cissy and Ellis Levine (zl) * * * * * * * * Published by Cissanell Publications PO Box 12811 London N20 8WB United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 © Sharon Faith and Deanna Levine First edition: February 2002 Second edition: July 2002 Third edition: 2003 Fourth edition: 2005 ISBN 0-9539213-1-X Fifth edition: 2006 ISBN 0-9539213-4-4 Sixth edition: 2008 ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 2 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Getting your Get Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB List of Contents Page Number Letters of endorsement. Quotes from letters of endorsement ……………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements. Family Law in England, Wales and Scotland. A note for the reader seeking divorce…………. 8 A note for the lawyer …………….…….. …………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 Legislation: England and Wales …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Legislation: Scotland ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 1. Who needs a Get? .……………………………………………………………………………….…………………... 14 2. What is a Get? ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 3. Highlighting the difficulties ……………………………………………………………………………….………….. 15 4. Taking advice from your lawyer and others ………………………………………………………………………. -

About the London Beth Din Published on United Synagogue (

About the London Beth Din Published on United Synagogue (https://www.theus.org.uk) About the London Beth Din Jewish life in England goes back almost 1000 years. It is believed that the first Jews were brought over from Normandy by William the Conqueror in 1066; there is reference to Jews in Oxford as early as 1075 and the Doomsday Book of 1086 records the Jew Mennasseh owning land in Oxfordshire. Several Baalei Tosafot (commentators) lived in England including R.Yaakov Mi’Orleans, (martyred in London at the coronation of Richard the Lionheart in 1189), R. YomTov Mi’Yoigny, author of Omnam Kein recited on Yom Kippur Maariv (martyred in the York massacre of 1190) and the R'i Mi’Londri, who is mentioned in the Remo in Hilchot Pesach (Siman 473 Sif 76) as recommending that the Hagadah be recited in the vernacular. In 1290, however, Jewish life in England came to abrupt end when the Edict of Expulsion was proclaimed by King Edward I, resulting in the banishment of the entire Jewish population from Britain. The Edict was issued on 18th July, which fell on Fast of Tisha B'Av. England remained "Yudenrein" free of Jews until 1656 when R. Menashe Ben Israel successfully petitioned Oliver Cromwell to allow the readmission of Jews. It is said that Menashe Ben Israel pressed Oliver Cromwell on the grounds that England -Angleterre- was one of the four "angles" of the earth referred to in the prophecies of the ingathering of the exiles, and thus resettlement would hasten the coming of the Messiah! Within only 50 years the offices of the Chief Rabbi and the London Beth Din came into being to provide a central religious authority for Jewish communities in London and throughout the United Kingdom - a role reflected in the London Beth Din's official title "D'Kehila Kedosha London Bet Din Vehamedina" - The Beth Din of London and the Country. -

The Marriage Issue

Association for Jewish Studies SPRING 2013 Center for Jewish History The Marriage Issue 15 West 16th Street The Latest: New York, NY 10011 William Kentridge: An Implicated Subject Cynthia Ozick’s Fiction Smolders, but not with Romance The Questionnaire: If you were to organize a graduate seminar around a single text, what would it be? Perspectives THE MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Marriage Issue Jewish Marriage 6 Bluma Goldstein Between the Living and the Dead: Making Levirate Marriage Work 10 Dvora Weisberg Married Men 14 Judith Baskin ‘According to the Law of Moses and Israel’: Marriage from Social Institution to Legal Fact 16 Michael Satlow Reading Jewish Philosophy: What’s Marriage Got to Do with It? 18 Susan Shapiro One Jewish Woman, Two Husbands, Three Laws: The Making of Civil Marriage and Divorce in a Revolutionary Age 24 Lois Dubin Jewish Courtship and Marriage in 1920s Vienna 26 Marsha Rozenblit Marriage Equality: An American Jewish View 32 Joyce Antler The Playwright, the Starlight, and the Rabbi: A Love Triangle 35 Lila Corwin Berman The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: How the Gender of the Jewish Parent Influences Intermarriage 42 Keren McGinity Critiquing and Rethinking Kiddushin 44 Rachel Adler Kiddushin, Marriage, and Egalitarian Relationships: Making New Legal Meanings 46 Gail Labovitz Beyond the Sanctification of Subordination: Reclaiming Tradition and Equality in Jewish Marriage 50 Melanie Landau The Multifarious -

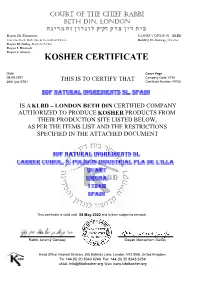

Kosher Certificate

COURT OF THE CHIEF RABBI BETH DIN, LONDON Dayan Ch. Ehrentreu, KASHRUT DIVISION - KLBD Emeritus Rosh Beth Din & Consultant Dayan Rabbi J. D. Conway, Director Dayan M. Gelley, Rosh Beth Din Dayan I. Binstock Dayan S. Simons KOSHER CERTIFICATE Date Cover Page 08.05.2021 Company Code: 5780 26th Iyar 5781 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT Certificate Number: 49755 IS A KLBD – LONDON BETH DIN CERTIFIED COMPANY AUTHORIZED TO PRODUCE KOSHER PRODUCTS FROM THEIR PRODUCTION SITE LISTED BELOW, AS PER THE ITEMS LIST AND THE RESTRICTIONS SPECIFIED IN THE ATTACHED DOCUMENT This certificate is valid until 08 May 2022 and is then subject to renewal. Rabbi Jeremy Conway Dayan Menachem Gelley Head Office: Kashrut Division, 305 Ballards Lane, London, N12 8GB, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 20 8343 6246 Fax: +44 (0) 20 8343 6254 eMail: [email protected] Web: www.klbdkosher.org COURT OF THE CHIEF RABBI BETH DIN, LONDON Dayan Ch. Ehrentreu, KASHRUT DIVISION - KLBD Emeritus Rosh Beth Din & Consultant Dayan Rabbi J. D. Conway, Director Dayan M. Gelley, Rosh Beth Din Dayan I. Binstock Dayan S. Simons KOSHER CERTIFICATE Date Page Number: 1 of 2 08.05.2021 Company Code: 5780 26th Iyar 5781 Certificate Number: 49755 The following products manufactured by BDF NATURAL INGREDIENTS SL, Spain at the factory site listed below are Kosher certified by the London Beth Din Kashrut Division (KLBD) for year round use when bearing the kosher logo and according to the Kosher status below. BDF Natural Ingredients SL Carrer Cuirol, 8, Polígon Industrial Pla de l'Illa Quart Girona 17242 Spain -

Product Directory 2021

STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 HOW TO USE THE PRODUCT DIRECTORY Products are Kosher for Passover only when the conditions indicated below are met. a”P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover only when bearing STAR-K P on the label. a/No “P” Required - These products are certified by STAR-K for Passover when bearing the STAR-K symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol followed by a “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement. No “P” Required - These products are certified for Passover by another kashrus agency when bearing their kosher symbol. No additional “P” or “Kosher for Passover” statement is necessary. Please also note the following: • Packaged dairy products certified by STAR-K areCholov Yisroel (CY). • Products bearing STAR-K P on the label do not use any ingredients derived from kitniyos (including kitniyos shenishtanu). • Agricultural products listed as being acceptable without certification do not require ahechsher when grown in chutz la’aretz (outside the land of Israel). However, these products must have a reliable certification when coming from Israel as there may be terumos and maasros concerns. • Various products that are not fit for canine consumption may halachically be used on Pesach, even if they contain chometz, although some are stringent in this regard. As indicated below, all brands of such products are approved for use on Pesach. For further discussion regarding this issue, see page 78. PRODUCT DIRECTORY 2021 STAR-K 2021 PESACH DIRECTORY BABY CEREAL A All baby cereal requires reliable KFP certification. -

The KA Kosher Certification

Kosher CertifiCation the Kashrut authority of australia & new Zealand the Ka Kosher CertifiCation he Kashrut Authority (KA) offers a wide range of exceptional T Kosher Certification services to companies in Australia, New Zealand and Asia. A trusted global leader in the field of Kosher Certification for more than a century, The Kashrut Authority is deeply committed to aiding clients on their kosher journey, helping to realise a profitable and long lasting market outlet for many and varied products. Accessing the kosher market offers a competitive edge, with vast potential on both a local and international scale. The Kashrut Authority believes in keeping the process simple, presenting a dedicated team and offering cutting edge technological solutions—The Kashrut Authority looks forward with confidence. 2 welCome n behalf of the entire KA Team, I am delighted to welcome O you to The Kashrut Authority, a dynamic organisation that has been instrumental in bringing kosher products to the people for more than a century. Our name, The Kashrut Authority, embodies who we are and what we do: kashrut is simply the Hebrew word for kosher, and we truly are authoritative experts in this field. Our KA logo is a proven trust–mark that consumers hold in the highest regard and we have extensive experience in helping clients with Kosher Certification for an incredible array of products. Our vast knowledge and experience in the kosher field helps each client on their kosher journey. Many of our clients have received KA Kosher Certification and, under the Kashrut Authority’s guidance, have been incredibly successful at both a local and global level. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

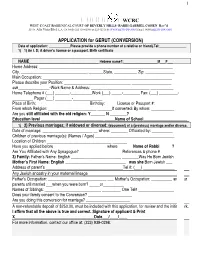

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Britain's Orthodox Jews in Organ Donor Card Row

UK Britain's Orthodox Jews in organ donor card row By Jerome Taylor, Religious Affairs Correspondent Monday, 24 January 2011 Reuters Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has ruled that national organ donor cards are not permissable, and has advised followers not to carry them Britain’s Orthodox Jews have been plunged into the centre of an angry debate over medical ethics after the Chief Rabbi ruled that Jews should not carry organ donor cards in their current form. London’s Beth Din, which is headed by Lord Jonathan Sacks and is one of Britain’s most influential Orthodox Jewish courts, caused consternation among medical professionals earlier this month when it ruled that national organ donor cards were not permissible under halakha (Jewish law). The decision has now sparked anger from within the Orthodox Jewish community with one prominent Jewish rabbi accusing the London Beth Din of “sentencing people to death”. Judaism encourages selfless acts and almost all rabbinical authorities approve of consensual live organ donorship, such as donating a kidney. But there are disagreements among Orthodox leaders over when post- mortem donation is permissible. Liberal, Reform and many Orthodox schools of Judaism, including Israel’s chief rabbinate, allow organs to be taken from a person when they are brain dead – a condition most doctors consider to determine the point of death. But some Orthodox schools, including London’s Beth Din, have ruled that a person is only dead when their heart and lungs have stopped (cardio-respiratory failure) and forbids the taking of organs from brain dead donors. As the current donor scheme in Britain makes no allowances for such religious preferences, Rabbi Sacks and his fellow judges have advised their followers not to carry cards until changes are made. -

Report of the Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Arica

REPORT OF THE REGULATORY BOARD OF BRIT MILAH IN SOUTH AFRICA (“THE REGULATORY BOARD”) 2016 - 2018 1 Background The Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Africa was established by Chief Rabbi Dr Warren Goldstein in 2016. The Regulatory Board acts in terms of the delegated authority of the Chief Rabbi and Head of the Beth Din (Court of Jewish Law), Rabbi Moshe Kurtstag. This report covers the activities of the Regulatory Board since inception in April 2016. The number of Britot reported are for the calendar years 2016 and 2017. The Regulatory Board is responsible for: 1.1 Ensuring the very highest standards of care and safety for all infants undergoing a Brit Milah and ensuring that this sacred and holy procedure is conducted according to strict Halachic principles (Jewish law); 1.2 The development of standardised guidelines, policies and procedures to ensure that the highest standards of safety in the performance of Brit Milah are maintained in South Africa; 1.3 Ensuring the appropriate registration, training, accreditation and continuing education of practising Mohalim (plural for Mohel, a person who is trained to perform a circumcision according to Jewish law); 1.4 Maintaining all records of Brit Milahs performed in South Africa; and 1.4 Fully investigating any concerns or complaints raised regarding Brit 1 Milah with the authority to recommend and to institute the appropriate remedial action. The current members of the Regulatory Board are: Dr Richard Friedland (Chairperson). Rabbi Dr Pinhas Zekry (Expert Mohel). Rabbi Anton Klein (Beth Din Representative). Dr Reuven Jacks (Medical Officer). Dr Joseph Spitzer (Mohel and Medical Adviser).