Arrangements and Editions of Public Domain Music: Originally in a Finite System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Law and Business: a Comprehensive Bibliography, 1982-1991 Gail I

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 4 Article 5 1-1-1991 Music Law and Business: A Comprehensive Bibliography, 1982-1991 Gail I. Winson Janine S. Natter Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Gail I. Winson and Janine S. Natter, Music Law and Business: A Comprehensive Bibliography, 1982-1991, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 811 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss4/5 This Special Feature is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Music Law and Business: A Comprehensive Bibliography, 1982-1991* By GAIL I. WINSON** AND JANINE S. NArrER*** Table of Contents I. Law Review and Journal Articles ......................... 818 A . A ntitrust ............................................ 818 B. Bankruptcy .......................................... 819 C. Bibliographies ....................................... 819 D . Contracts ........................................... 819 1. M anagem ent ..................................... 821 2. Personal Service ................................ -

Sampling and Remixes

DE FR EN SEARCH Sampling and Remixes The articles about arrangements in the “Good to know” series have so far focused on “conventional” arrangements of musical works. Sampling and remixes are two additional and specic forms of arrangement. What rights need to be secured when existing recordings are used to produce a new work? What agreements have to be contracted? Text by Claudia Kempf and Michael Wohlgemuth From the copyright point of view, remixes and sampling are specic forms of arrangement. (Photo: Tabea Hüberli) Sound samplings come in many dierent forms and techniques. But they all have one thing in common: they incorporate parts of a musical recording into a new work. This regularly raises the question whether such parts of works or samples are protected by copyright or – especially in the case of very short sound sequences – whether they may be used freely. In the case of a remix, an existing production is taken and re-arranged and re-mixed. This may involve taking apart a whole work and putting it together again with the addition of new elements. Theoretically, the degree of re-arrangement in a remix may range from a simple cover version to a completely new arrangement. As a rule, a remix is simply an arrangement. Remixes generally keep a work’s existing title and add a tag which refers either to the form of use (radio edit / extended club version, or similar) or the name of the remixer (generally a well-known DJ). By contrast with conventional arrangements, in addition to using an existing work to create a derived work or arrangement, samples and remixes also use an existing sound recording. -

Glossary for Music the Glossary for Music Includes Terms Commonly Found in Music Education and for Performance Techniques

Glossary for Music The glossary for Music includes terms commonly found in music education and for performance techniques. The intent of the glossary is to promote consistent terminology when creating curriculum and assessment documents as well as communicating with stakeholders. Ability: natural aptitude in specific skills and processes; what the student is apt to do, without formal instruction. Analog tools: category of musical instruments and tools that are non-digital (i.e., do not transfer sound in or convert sound into binary code), such as acoustic instruments, microphones, monitors, and speakers. Analyze: examine in detail the structure and context of the music. Arrangement: setting or adaptation of an existing musical composition Arranger: person who creates alternative settings or adaptations of existing music. Articulation: characteristic way in which musical tones are connected, separated, or accented; types of articulation include legato (smooth, connected tones) and staccato (short, detached tones). Artistic literacy: knowledge and understanding required to participate authentically in the arts Atonality: music in which no tonic or key center is apparent. Artistic Processes: Organizational principles of the 2014 National Core Standards for the Arts: Creating, Performing, Responding, and Connecting. Audiate: hear and comprehend sounds in one’s head (inner hearing), even when no sound is present. Audience etiquette: social behavior observed by those attending musical performances and which can vary depending upon the type of music performed. Benchmark: pre-established definition of an achievement level, designed to help measure student progress toward a goal or standard, expressed either in writing or as an example of scored student work (aka, anchor set). -

Album Hunter Mp3 Download Album Hunter Mp3 Download

album hunter mp3 download Album hunter mp3 download. A fan-arrangement album celebrating the music and franchises from Super Smash Bros , featuring musicians from around the world. Harmony of Heroes is a Super Smash Bros fan-arrangement album celebrating and paying tribute to the music of Super Smash Bros, Super Smash Bros. Melee and Super Smash Bros. Brawl. It is a collaborative effort made up of musicians on a global scale, ranging from digitally synthesised music to live performances covering a variety of different genres. The diversity of the album allows us to reach out to many different types of fans no matter their musical preference. The album builds upon the success of Harmony of a Hunter and Harmony of a Hunter: 101% Run, two Metroid focused albums marking the 25 th Anniversary of the Metroid franchise. Both of these albums covered the majority of music present in Metroid games at that time, and Smash Bros felt like the next natural step in an effort to reach out to even more people. The name Heroes was chosen to describe the characters we choose in Super Smash Bros, the ones who help us reign triumphant in those epic brawls. They are our heroes. Our album is vast in content, covering the majority of franchises featured in these titles. While you can expect to hear iconic themes representing some of the game’s most notable additions, you may be surprised to find we have covered some of the more obscure ones too. In some cases, we haven’t been afraid to experiment a little, offering a fresh perspective to those who listen. -

Copyright Basics

PCC Print Center Sylvania Campus Copyright Basics 12000 SW 49th Ave, CC116 Portland, OR 97216 A Brief Overview of Copyright Law pcc.edu/printcenter & Best Practices Phone: 971-722-4670 PCC Written, Illustrated & Produced by: PANTHER Email: [email protected] PRESS The PCC Print Center Greetings Thank you for choosing the PCC Print Center for your print, design, and communication needs. We serve the PCC community and the greater Portland area. We are committed to the PCC mission and towards being good stewards of the taxpayer’s dollars. In doing this work, we must maintain a delicate balance between protecting the rights of copyright holders, fair use practices, and ensuring the taxpayer, PCC, and the students are not impacted by mistakes that can be avoided. In this booklet we will discuss the basics of copyright, best practices, and how you can respect and protect your own and someone else’s intellectual properties. Attention!! These materials are not a comprehensive overview of copyright law. There are many factors that need to be examined to make a clear judgment; such as different US Codes, international law, litigation rulings, and active cases that create a constantly evolving legal landscape. This is a reference guide to help identify Copyright concerns, offer best practices to avoid infringing on Copyrighted materials, as well as how to protect your own Intellectual Properties. This booklet is not a replacement for legal council from a certified professional. Any serious questions should be discussed with a licensed attorney. For more resources, information, questions about PCC’s copyright policy, or to report a copyright concern. -

Music in the Public Domain Free Download

Music in the public domain free download So you've scoured the internets in search of music recordings in the Public Domain and found bupkis If only someone would have gone out and. Royalty Free Music Resource. Free song downloads for your films, movie scores, Youtube videos, class projects, elevator, on hold, commercial & personal use.Orchestra Music · Royalty Free Music for · Royalty Free Instrumental · Jazz. Dan-O is a composer that offers his original songs for free download at Public domain music, video and other content can be used in any way. To find these songs, just click on the "Public Domain" box at the bottom Are you interested in sharing your music with us under the Public Domain dedication? The Free Music Archive offers free downloads under Creative. These recordings of Public Domain Hymns include beautiful contemporary arrangements as well as "straight from the hymn book" versions. If you need hymn. Here are seven sources for free public domain music that you can use to download great, free music. Expand your music collection, for free! Musopen is a non-profit offering free access to sheet music, royalty free public domain music recordings, and other music resources. Classic recordings ripped from 78 RPM vinyl records for you to enjoy as free, legal mp3s. No signup no spam just great music. Blues, folk, jazz, classical gems. Sources of free public domain, royalty free music. Google's YouTube audio library - free downloads for use in videos (not for audio redistribution or site. Listen to songs and albums by Public Domain Royalty Free Music, including "Deck the Halls, Christmas Song Instrumental (feat. -

How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 Comments

Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can I : Ask.Au... Page 1 of 6 Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 comments Understanding some key universal concepts around arrangement, dynamics and composition can help you take your tracks to the next level. Here's how. Whether you’re in the studio or on stage, just having a strong song and performing it well is not enough. You also need a smart arrangement in order for your song to have its maximum impact. Giving your arrangement a dramatic arc helps make it more interesting and accessible to listeners. It's beyond the scope of this article to focus on specific instruments and how to arrange them for particular musical genres—that would require a series of books—but the aim here is to cover some global arranging concepts, which will apply no matter what the specific style or instrumentation. Contrast is King Just like a painting, a song arrangement needs contrast. If everything is too similar, it will be boring and the listeners will tune out. You want to keep their attention, so you should structure the song so that it’s not static. Think of it almost like a book or play, which has a beginning a middle and an end. You have a number of tools at your disposal for creating drama and interest with your arrangement, which include varying the dynamics, adding to the instrumentation as you go, and building the complexity of the instrument and vocal parts as the song progresses. -

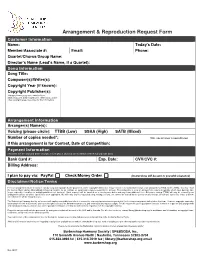

Arrangement & Reproduction Request Form

Arrangement & Reproduction Request Form Customer Information Name: Today’s Date: Member/Associate #: Email: Phone: Quartet/Chorus/Group Name: Director’s Name (Lead’s Name, if a Quartet): Song Information Song Title: Composer(s)/Writer(s): Copyright Year (if known): Copyright Publisher(s): (Research www.ascap.com, www.bmi.com, www.sesac.com, www.songfile.com, sheet music, and/or other copyright-related resources for this information) Arrangement Information Arranger(s) Name(s): Voicing (please circle): TTBB (Low) SSAA (High) SATB (Mixed) Number of copies needed*: *(One copy per singer is required by law) If this arrangement is for Contest, Date of Competition: Payment Information (You will not be charged until clearance is in place and you are notified of the total amount due.) Bank Card #: Exp. Date: CVV/CVC #: Billing Address: I plan to pay via: PayPal ccc Check/Money Order ccc (Instructions will be sent to you with clearance) Disclaimer/Notice/Terms Fees for arrangement music clearances vary by song and copyright holder (publisher). Some copyright holders also charge extra fees for additional voicings of an arrangement (TTBB, SSAA, SATB). You may email the Society Music Library ([email protected]) anytime for an estimate on a particular song you would like to arrange. Processing time to clear an arrangement request is typically 30-60 days, but may take longer especially if medleys or multiple publishers are involved. Rush requests will be handled on a case-by-case basis and may incur additional fees. Only male voicing (TTBB) will only be cleared for an arrangement unless otherwise specified on your application. -

MM Discography -- Others Updated 2016

MONDAY MICHIRU DISCOGRAPHY -- OTHERS 1976 Toshiko Akiyoshi & Lew Tabackin Big Band "Insights" album (RCA) -- vocals 1980 Toshiko Akiyoshi Trio & Flute Quartet "Tuttie Flutie" album (Discomate Records) -- flute 1991 System 7 "Freedom Fights" single (Ten Records) -- vocals 1992 "Jazz Hip Jap" compilation CD (NEC Avenue) -- co-writer, arranger & vocals 1993 United Future Organization "United Future Organization" album and single "My Foolish Dream" (Brownswood Records) -- co-writer and vocals BBF & Zum Zum Allstars "Zum Zum Paradise" album (Ki/oon Sony Records) -- co-writer and vocals "Jazz Hip Jap 2" compilation CD (NEC Avenue) -- co-writer, arranger and vocals 1994 Remix Trax Vol. 6 "Japanese New Vibes" compilation album (Meldac) -- co-writer and vocals DJ Krush "Krush" album (Chance Records) -- co-writer and vocals "Yeah!" compilation CD (Kitty) -- song licensed from "Maiden Japan" album Audio Sports "Strange Fruits" album (All Access) -- co-writer and vocals Kyoto Jazz Massive "Kyoto Jazz Massive" album (For Life) -- vocals "Cool Struttin' Volume 3" compilation album (Amber/Polydor) -- song licensed from "Maiden Japan" album Picasso "Breakfast Newspaper" album (Kitty) -- lyrics and vocals 1995 Eiki Nonaka "a-key" album (Mercury Records) -- writer and vocals "Cutie Collection" compilation album (Media Remoras) -- co-writer and vocal production "Jazz Moments by Heineken Volume 1" album (Polydor) -- compiled by myself "Denz da Denz Vol. 2" compilation CD (Basic Beats) -- song licensed from "Adoption Agency" album Mondo Grosso "Born Free" -

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and Their Fans

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Annie Lyons TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 2020 __________________________________________ Renita Coleman Department of Journalism Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Hannah Lewis Department of Musicology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Annie Lyons Title: One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Supervising Professors: Renita Coleman, Ph.D. Hannah Lewis, Ph.D. Boy bands have long been disparaged in music journalism settings, largely in part to their close association with hordes of screaming teenage and prepubescent girls. As rock journalism evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, so did two dismissive and misogynistic stereotypes about female fans: groupies and teenyboppers (Coates, 2003). While groupies were scorned in rock circles for their perceived hypersexuality, teenyboppers, who we can consider an umbrella term including boy band fanbases, were defined by a lack of sexuality and viewed as shallow, immature and prone to hysteria, and ridiculed as hall markers of bad taste, despite being driving forces in commercial markets (Ewens, 2020; Sherman, 2020). Similarly, boy bands have been disdained for their perceived femininity and viewed as inauthentic compared to “real” artists— namely, hypermasculine male rock artists. While the boy band genre has evolved and experienced different eras, depictions of both the bands and their fans have stagnated in media, relying on these old stereotypes (Duffett, 2012). This paper aimed to investigate to what extent modern boy bands are portrayed differently from non-boy bands in music journalism through a quantitative content analysis coding articles for certain tropes and themes. -

Artarr Press Release Edit 3

***For Immediate Release*** Media Contact: Jesse P. Cutler JP Cutler Media 510.338.0881 [email protected] GRAMMY® Award-Winning Doug Beavers Releases New Album Art of the Arrangement Featuring Pedrito Martinez, Ray Santos, Oscar Hernández, Jose Madera, Angel Fernandez, Marty Sheller, Gonzalo Grau, Herman Olivera, Luques Curtis and More! New York, NY -- Tuesday, July 18, 2017 -- On his previous release, 2015’s Titanes del Trombón, the GRAMMY® Award-win- ning Doug Beavers -- as the album’s title suggested -- focused on honoring his fellow trombonists and pioneers such as J.J. John- son, Barry Rogers and Slide Hampton. The recording received universal praise with Jazzwax magazine calling it “absolutely hypnotic” and Latin Jazz Network deeming the release a “precious and significant work.” Publications as prestigious as Downbeat, JAZZIZ and Latino Magazine also joined in the chorus, each providing feature space to this magnificent project that paid tribute to some of the unsung masters of an often underappreciated instrument. At the time of the release of Titanes del Trombón, Beavers took note of the fact that many of the great trombonists of the past were also first-rate arrangers, and that steered him toward the music that now comprises his latest release, Art of the Arrangement (ArtistShare, August 25, 2017). The new collection is an homage to the greatest Latin jazz and salsa arrangers of our time, includ- ing Gil Evans, Ray Santos, Jose Madera, Oscar Hernández, Angel Fernandez, Marty Sheller, and Gonzalo Grau. Through- out the history of Latin jazz, and jazz in general, it’s the arrangers who have shaped the music, and quite often their contributions have been overlooked, or ignored altogether. -

The Need for More Certainty of Copyright Status for Classical Music Works Published Between 1925 and 1978*1

IF IT IS BAROQUE, FIX IT: THE NEED FOR MORE CERTAINTY OF COPYRIGHT STATUS FOR CLASSICAL MUSIC WORKS PUBLISHED BETWEEN 1925 AND 1978*1 I. INTRODUCTION Classical music is all around us. Although dismal concert attendance numbers suggest otherwise, classical music still has an important place in modern culture—from elevating emotions in film soundtracks to wooing consumers through television commercials.2 Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt appeared in a Coca-Cola commercial aired during the Pyeongchang 2018 Olympics.3 Advertising agencies have used Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s famous 1812 Overture to sell products ranging from breakfast cereal to a drug that treats overactive bladder.4 Independence Day celebrations around the nation also frequently feature the piece.5 Nonclassical artists surreptitiously submerge classical works into popular music. The verse of Eric Carmen’s song “All by Myself,” also covered by Celine Dion,6 originates in Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2 in C Minor.7 Rapper Nas used Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Für Elise” throughout his song “I Can.”8 Nas also used Frédéric Chopin’s Étude in C Minor, op. 10, no. 12 in his song “A Queens Story.”9 Lady Gaga’s hit song “Alejandro” begins with Vittorio Monti’s Czardas,10 which itself comes from a traditional Hungarian folk dance.11 Ludacris’s song “Coming 2 America” cleverly and appropriately contains Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9 in E Minor, op. * Yunica Jiang, J.D. Candidate, Temple University Beasley School of Law, 2020. I would like to thank Professor Erika Douglas for her feedback, guidance, support, and encouragement throughout this process.