Paralytic Poliomyelitis: a Forgotten Diagnosis?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Highpark and St Cuthbert's Primary Schools, Westercommon

Pre-12 Education Strategy Phase 4B– New Highpark and St Cuthbert’s Primary Schools, Westercommon Early Years Centre and Highpark Autistic Unit – Award of contract approved – Declaration of interest. 13 There was submitted a report by the Executive Director of Development and Regeneration Services regarding the tender received for Phase 4B of the pre-12 Education Strategy for New Highpark and St Cuthbert’s Primary Schools, Westercommon Early Years Centre and Highpark Autistic Unit, advising (1) that during the design and planning application process for the construction of a new multiplex primary school with early years facilities and autistic unit to replace the existing provision at Ruchill, Westercommon and Our Lady of the Assumption and St Cuthbert’s Primary Schools, Westercommon Nursery School and Ruchill Autistic Centre to be built in an area of Ruchill Park with access to the east through the disused Ruchill Hospital, it had become clear that the proposed access road would not be developed as part of the proposed residential development of the adjacent Ruchill Hospital site as was originally envisaged as the preferred developers appointed by Scottish Enterprise had withdrawn from the development; (2) that it had been necessary to procure the access road under a license agreement with Scottish Enterprise and Development and Regeneration Services had undertaken the design of the access road to tie in with the tender programme for the school and the procurement requirements and negotiations were underway with Scottish Enterprise to secure a 50% contribution; (3) that ABC had been requested to procure the works for the contract by producing traditional tender documentation and seeking a tender return from City Building (Glasgow) LLP; (4) of the tender process; and (5) that following a devised set of criteria by Development and Regeneration Services, it had been determined that the tender from City Building (Glasgow) LLP represented Best Value to the Council. -

Mental Health Services North East Sector Annual Report 2003/04

NorthEast Sector Annual Report 2003 – 2004 The new Arran Centre The new Easterhouse Community Health Centre – incorporating Auchinlea Resource Centre and the previous Health Centre 1 Section 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The last year within the North East sector has been another period of significant activity. In comparing the prospective developments from last year’s report, much has been achieved and this introduction will cover some of these achievements later on. Firstly though it is worth recalling that the driver for the production of Annual Reports came from what was then the Divisional Clinical Governance Committee. The North East Sector received very positive feedback when the sector report was presented to the committee last year and also by written feedback in the form of a standard evaluation report. Looking back over the past year and the targets that were set then, the following key milestones have been achieved: • Wyndford Lock Nursing Home has been closed and patients have been accommodated in alternative forms of accommodation. All staff have been redeployed to alternative posts. • A new North East addiction Unit is about to open at Stobhill which will mean that Ruchill Hospital will at last benefit from improved patient activity space and staff will have some changing facilities. It will also result in a reduction of admission beds in each ward from 30 to 24, creating much needed patient activity space at Parkhead. • A new North East IPCU will open within the next few weeks at Stobhill which will have dedicated Consultant and Staff Grade Psychiatrist cover. This will also increase the amount of much patient activity space at Parkhead Hospital. -

Mental Health Bed Census

Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Data Collection Documentation Document Type: Guidance Notes Collections: 1. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census: One Day Audit 2. Mental Health and Learning Disability Patients: Out of Scotland and Out of NHS Placements SG deadline: 30th November 2014 Coverage: Census date: Midnight, 29th Oct 2014 Page 1 – 10 Nov 2014 Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Document Details Issue History Version Status Authors Issue Date Issued To Comments / changes 1.0 Draft Moira Connolly, NHS Boards Beth Hamilton, Claire Gordon, Ellen Lynch 1.14 Draft Beth Hamilton, Ellen Lynch, John Mitchell, Moira Connolly, Claire Gordon, 2.0 Final Beth Hamilton, 19th Sept 2014 NHS Boards, Ellen Lynch, Scottish John Mitchell, Government Moira Connolly, website Claire Gordon, 2.1 Final Ellen Lynch 9th Oct 2014 NHS Boards, Further clarification included for the following data items:: Scottish Government Patient names (applicable for both censuses) website ProcXed.Net will convert to BLOCK CAPITALS, NHS Boards do not have to do this in advance. Other diagnosis (applicable for both censuses) If free text is being used then separate each health condition with a comma. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census o Data item: Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis on admission Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. o Data item: Last known Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. -

Presentation Title

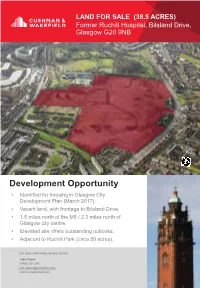

LAND FOR SALE (38.5 ACRES) Former Ruchill Hospital, Bilsland Drive, Glasgow G20 9NB Development Opportunity • Identified for housing in Glasgow City Development Plan (March 2017). • Vacant land, with frontage to Bilsland Drive. • 1.5 miles north of the M8 / 2.3 miles north of Glasgow city centre. • Elevated site offers outstanding outlooks. • Adjacent to Ruchill Park (circa 50 acres). For more information, please contact: Jake Poole 07885 251 090 [email protected] cushmanwakefield.com LAND FOR SALE (38.5 ACRES) Former Ruchill Hospital, Bilsland Drive, Glasgow G20 9NB SECC & SSE HYDRO RIVER CLYDE CITY CENTRE PARK CIRCUS WEST END M8 BOTANIC GARDENS MARYHILL ROAD (A81) GARSCUBE ROAD FIRHILL STADIUM RUCHILL PARK BENVIEW CAMPUS PANMURE STREET BILSLAND DRIVE For more information, contact: cushmanwakefield.com LAND FOR SALE (38.5 ACRES) Former Ruchill Hospital, Bilsland Drive, Glasgow G20 9NB LOCATION The site is located 1.5 miles north of the M8 as it skirts the northern edge of Glasgow city centre. From the M8 and city centre the main arterial road connections are via Maryhill Road, Garscube Road and Craighall Road. The northeast corner of the site is less than a 500m walk from the Possilpark and Parkhouse Railway Station. A number of bus services run along Bilsland Drive, Panmure Street and nearby Balmore Road. In terms of education opportunities, the site wraps around the relatively new Benview Campus near the top of the site, which includes both St Cuthbert’s Primary and Highpark Primary. The East Park special needs school on Maryhill Road targets children from 5-19 years of age. -

Selected Summarie

180 THE NATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL OF INDIA VOL. 8, NO.4, 1995 5 to 6 minutes and after 30 cycles one target DNA fragment infrequent to isolate either M. tuberculosis or Mycobacterium can be magnified one million times and is then detected by avium-intracellulare from blood. Since 6 of the 8 patients less sensitive methods such as hybridization with DNA were HIV-positive, the results are not unexpected. probes. While the detection level of DNA hybridization is It is interesting that 1 of the 8 patients was not immuno- 50 pg which is contained in about 10000 bacilli (the detection compromised and had no clinical feature of disseminated sensitivity of Ziehl-Neelsen staining is also 10 000 bacilli}, tuberculosis but was still positive by PCR. If this finding is using PCR it is possible to obtain a positive signal even when borne out by testing in a larger number of immunocompetent one bacterial genome is present. I patients it may offer a method for definitive diagnosis in The insertion sequence (IS) 6110 is a transposon which is patients where the site is inaccessible or where the relevant present in multiple copy numbers (varying from 1 to 15) in sample is difficult to obtain. members of the M. tuberculosis complex and has not been reported in any other mycobacterial species. However, PCR REFERENCES has been reported to give false-positive results (due to carry Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S, Scharf S1, Higuchi R, Horn GT, et at. over of amplicons) as well as false-negative (due to presence Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. -

National Mental Health Services Assessment

Greater Glasgow NATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES ASSESSMENT LOCALITY REPORT GREATER GLASGOW December 2003 Greater Glasgow Introduction The remit for the National Assessment means that the focus in the locality reports is on what needs to be done locally to deliver the new provisions of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003. With that in mind the many examples of good care seen across Scotland are not covered in the individual reports. This should not be taken as a negative. Every effort has been made to achieve consistency in each report. There are however variations in those cases where the local arrangements vary sufficiently to warrant some variety in the presentation of findings. For example not all information was available for or from each area in the same format or with the same coverage and where this is the case it is stated. The wide-ranging nature of the responsibilities that the Act places on local authorities means that it was virtually impossible to assess the services provided by them or the voluntary sector in a short timescale, although there are examples of services across Scotland in the Full Report. In no way should this be seen as devaluing the local authority contribution or minimising the additional demands placed on the Councils. The findings arising from the visits and review of existing information can only represent a snapshot in time and in many cases the local situation will now be different. However, the purpose is to provide a shared, validated information base to start from and to plan for the successful and timely implementation of the new legislation. -

Minutes of the Ruchill Community Council Held in the Community Centre, Bilsland Drive, Ruchill G20 9NF on Wednesday 2Nd February 2016 at 6.30Pm

Item 11e 1 August 2016 Minutes of the Ruchill Community Council held in the Community Centre, Bilsland Drive, Ruchill G20 9NF on Wednesday 2nd February 2016 at 6.30pm Attending: Flo McGrehan Kate Mulgrew Eleanor Brown Kate Mulgrew Suzanne Halliday Councillor Chris Kelly Councillor Helen Stephen Councillor Kieran Wild Patricia Ferguson MSP Dawn Baird, Maryhill HA Officers Sam Green and Robert Keegan Apologies: Bob Doris MSP, Fran O’rourke 1.0 Welcome Eleanor welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2.0 Minutes of Last Meeting 2.1 The minutes of Wednesday 2nd December were adopted: proposed by Suzanne and 2nd by Kate Mulgrew. 3.0 Matters arising from Minutes of Last Meeting 3.1 No matters arising from previous meetings. 4.0 Police Business 4.1 Officers were in attendance and gave residents the following breakdown: of incidents for the last 5 weeks Area Ruchill Offences Total Incidents Street drinking 3 Breach of the peace 5 Vandalism 4 Dangerous driving 1 No insurance 1 Theft of a motor vehicle 2 Theft from motor vehicle 2 1 2 Theft 1 Fraud 1 H/B with intent 1 Possession 4 Indecent Assault (Historical) 1 Rape (Historical) 1 Dangerous Driving 1 No insurance 1 Common assault 2 Police obstruction 2 Breach of bail 1 Dangerous dogs act 1 Marion asked if there has been any issues at the Sanctuary new build site. There have been no calls to these sites. Officers noted that it was encouraging that crime had gone down so much in Ruchill over the last few years. Officer Sam Green plans on attending the youth session at NUC on Saturday morning. -

Fetal Damage After Accidental Polio Vaccination of an Immune Mother

Fetal damage after accidental polio vaccination of an immune mother A. E. BURTON, MB, MRCGP E. T. ROBINSON, MB, FRCGP W. F. HARPER, FRCS(Glas.), FRCOG E. J. BELL, PH.D, MRC.PATH J. F. BOYD, MD, FRCP(Edin.), FRC.PATH, FRCP(Glas.) SUMMARY. Irreparable damage to the anterior British National Formulary (1981) recommends the use horn cells of the cervical and thoracic cord was of inactivated polio vaccine in pregnancy. We have found in a 20-week-old fetus whose mother was failed to discover any reference to fetal infection after immune to poliomyelitis before conceiving but oral polio vaccine in pregnancy. We describe a fetus who was inadvertently given oral polio vaccine at with irreparable damage to the anterior horn cells of the 18 weeks gestation. Polio neutralizing antibody spinal cord whose mother was immune to poliomyelitis titres in sera, taken before and after pregnancy, prior to conceiving but who was accidentally given oral were identical and were at levels normally re- polio vaccine early in pregnancy. garded as providing protection. Unsuccessful at- tempts were made to isolate poliovirus from Case report extracts of fetal brain, lung, liver and placenta. on The patient was a 19-year-old unmarried girl, employed as a Fluorescent antibody tests were performed student nurse. She first consulted on 7 May 1980 because of various levels of the central nervous system and six weeks amenorrhoea, her last menstrual period being 26 on the left and right extensor forearm muscles. March 1980. She had previously taken the oral contraceptive Specific positive fluorescence to poliovirus 2 and Eugynon 30. -

Ruchill and Possilpark Thriving Place Our

Ruchill and Possilpark Thriving Place Our Community Plan (24.08.17 Draft) Page 1 of 27 What is our community plan? Our community plan is the Locality Plan for Ruchill and Possilpark. It is one of the ways that Glasgow’s Community Planning Partnership will be trying to tackle inequalities; supported by Glasgow City Council’s Local Outcome Improvement Plan. Our community plan has been produced by people who live or work in Ruchill and Possilpark. It tries to tell the story of the area so far and sets out how together local people, organisations and services can make changes that local people would like to see in Ruchill and Possilpark over the next ten years. Our plan tells you about the work that has been done so far by local people, organisations and collaboratively through Thriving Places. It sets out what we hope to achieve together. Our plan describes different ways you can get involved in achieving change in Ruchill and Possilpark if you want to participate. All our partners within Community Planning are fully committed to the delivery of these plans. Without local people and our partners working together we cannot achieve what these plans set out. If you want to get involved you can do so by contacting the North West Community Planning Partnership and Development Officer Linda Devlin at [email protected] Statement of Intent This community plan is committed to tackling inequality in Ruchill and Possilpark. We believe this can be achieved by: using an Asset Based Community Development approach to create stronger, safer, -

Item 4 18Th January 2011 Glasgow City Council

Item 4 18th January 2011 Glasgow City Council Canal Area Committee Report by Executive Director of Development and Regeneration Services Contact: S Dynowski Ext: 79905 Overview of Development and Regeneration Services Purpose of Report: This paper provides an overview of Development and Regeneration Services (DRS), and highlights some of the main developments and activities within the Canal area. Recommendations: It is recommended that Committee note the contents of this paper, and the contribution of DRS to the development and regeneration of the Canal area. Ward No(s): 16 Canal Citywide: Local member(s) advised: Yes No Consulted: Yes No PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING: Any Ordnance Survey mapping included within this Report is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function to make available Council-held public domain information. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey Copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/map data for their own use. The OS web site can be found at “<http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk>". If accessing this Report via the Internet, please note that any mapping is for illustrative purposes only and is not true to any marked scale. 1 BACKGROUND 1.1 This paper provides an overview of Development and Regeneration Services (DRS) and highlights some of the main developments and activities within Ward 16 Canal. 2 OVERVIEW OF DRS 2.1 DRS has created a vision for the future that clearly sets out its intentions in carrying out its role and the overall impact it aims to have on the city and its people. -

Evening Times Roll of Honour January to April 1918

EVENING TIMES ROLL OF HONOUR JANUARY TO APRIL 1918 Surname First name Home Rank Regiment Date of Death Date in ET Page Port Notes Abbott Joseph Glasgow Private Cameron Highlanders 22-Mar-18 30-Apr-18 4 Y Killed in action Acton JJ Second Lieutenant South Lancashire Regiment 05-Jan-18 4 Wounded Adair John Rutherglen Driver Royal Engineers 12-Jan-18 07-Feb-18 5 Y Died of wounds Adam John Glasgow Private Highland Light Infantry 06-Jul-15 16-Apr-18 12 Fell in action Adams John Glasgow Private Royal Scots 28-Apr-17 08-Mar-18 5 Y Previously reported missing, now presumed killed Aird Joe Clydebank Private Royal Scots Fusiliers 22-Mar-18 15-Apr-18 8 Killed in action Aird Joseph Clydebank Private Royal Scots Fusiliers 22-Mar-18 26-Apr-18 3 Y Killed in action Aitchison Charles Hamilton Private Northumberland Fusiliers 09-Apr-17 09-Apr-18 9 Killed Aitken Alexander Glasgow Private Scottish Rifles 01-Feb-18 5 Y Killed Aitken James Bellshill Private Gordon Highlanders 28-Mar-18 18-Apr-18 5 Y Killed in action Aitken William H Glasgow Private 25-Mar-18 18-Apr-18 12 Killed in action Alexander F Glasgow Private King's Own Scottish Borderers 03-May-17 25-Mar-18 9 Y Previously reported missing, now presumed killed Alexander George Glasgow Private Gordon Highlanders 01-Dec-17` 24-Jan-18 5 Y Died of wounds Alexander Patrick David Glasgow Gunner Royal Garrison Artillery 01-Apr-18 3 Y Died of wounds Allan Alexander Deacon Glasgow Able Seaman Royal Naval Division 28-Mar-18 12-Apr-18 5 Y Died from wounds received in action Allan James Kirkintilloch Corporal Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders 29-Jan-18 6 Y Awarded Military Medal Allan James Atkinson Springburn Quartermaster-Sergeant Royal Scots 28-Apr-17 27-Apr-18 8 Killed in action in France. -

Fill This Space Infectious Diseases Update

Digest/Update Irish immigrants have their immigrants had a standardized mortality these trends as large-scale Irish immigra- ratio a little lower than the female popula- tion is likely to continue. problems too tion in Ireland and a little higher than the (C.D.) D ECAUSE of longstanding free access total female population in England and Source: Adelstein AM, Marmot MG, Dean G, Lbetween both countries, there is an Wales. Mortality in both sexes was Bradshaw JS. Comparison of mortality of Irish established pattern of Irish emigration to highest, relative to Ireland, in conditions immigrants in England and Wales with that of Britain, especially in times of economic with a behavioural background, such as Irish and British nationals. Ir Med J 1986; 79: depression such as during the great famine smoking-related cancers, obstructive air- 185-189. of 1845-49, the 1930s, the 1950s and most ways disease, peptic ulcer, cirrhosis, ac- Contributors: D. Jewell, T. O'Dowd, C. Daly. recently in the mid-1980s. In 1971 1.8% cidents, poisoning and violence, and in of the population of England and Wales tuberculosis as well. had been born in both parts of Ireland. Ease of migration may mean that ill FILL THIS SPACE While Irish immigrants do not generally health and economic and social disadvan- Contributions to the Digest pages are share the linguistic, racial and broad tage, rather than acting as a barrier, may welcome from all readers. These cultural disadvantages of other im- act as a spur to migration. A change from should be from recent papers in migrants, -they tend to be from the lower the rural Irish environment to the in- research journals which general prac- social classes and have predictable mor- dustrial environment of England, and titioners might not normally read.