Requesting a Challenge Inspection Against Syria Under the Chemical Weapons Convention: Venturing Into Uncharted Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Annual Report of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2019

The Annual Report of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2019 A Destroyed State and Displaced People Thursday, January 23, 2020 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R200104 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction II. Executive Summary III. Comparison between the Most Notable Patterns of Human Rights Violations in 2018 and 2019 IV. Major Events in 2019 V. Most Prominent Political and Military Events in 2019 VI. Road to Accountability; Failure to Hold the Syrian Regime Accountable Encouraged Countries in the World to Normalize Relationship with It VII. Shifts in Areas of Control in 2019 VIII. Report Details IX. Recommendations X. References I. Introduction The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-govern- mental, non-profit independent organization that primarily aims to document all violations in Syria, and periodically issues studies, research documents, and reports to expose the perpetrators of these violations as a first step to holding them accountable and protecting the rights of the victims. It should be noted that Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has relied, in all of its statistics, on the analysis of victims of the conflict in Syria, on the Syrian Network for Human Rights as a primary source, SNHR also collaborate with the Independent Inter- national Commission of Inquiry and have signed an agreement for sharing data with the Independent International and Impartial Mechanism, UNICEF, and other UN bodies, as well as international organizations such as the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. -

The Syrian Civil War: Analysis of Recent Developments by Dr. Sohail

The Syrian Civil War: Analysis of Recent Developments By Dr. Sohail Mahmood On April 7, 2018 an alleged chemical weapons attack took place in Douma, Syria in which 70 people were killed.1 Russia and the Syrian government denied using chemical weapons fight against rebels in Eastern Ghouta, Syria and its ally Russia deny any chemical attack took place - with Russia calling it a "staged thing”. The rebel Syria Civil Defense Force says more than 40 people were killed and entire families were gassed to death in the attack, which drew global outrage. President Trump blasted "that animal" Syrian President Bashar Assad and said blame also fell on Russia and Iran for supporting his regime. Prime Minister Theresa said there was "unmistakable evidence" Syria was behind the attack. “No other group could have carried this out," May said. A year ago, Syria was accused of using sarin gas in an attack in the town of Khan Shaykhun. An investigation by the U.N. and OPCW concluded the Syrian air force had used the gas in its attack, which killed almost 100.2 Assad’s position in the Syrian civil war is unassailable. He is supported by Iranian-back fighters as well as the Russian air force, has cemented his control over most of the western, more heavily populated, part of the country. Rebels and jihadist insurgents are largely contained to two areas along Syria’s northern and southern borders.3 Syria's war, now in its eighth year, has seen the opposition make gains up until Russia entered the war in support of Assad in 2015. -

Ni Romain, Ni Arabe, Moundar Bar Hareth, Roi Des Tayyés. Quand L'arabie Était Chrétienne

Ni Romain, ni Arabe, Moundar bar Hareth, roi des Tayyés. Quand l'Arabie était chrétienne Mémoire Nicolas Asselin Maîtrise en études anciennes - avec mémoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Nicolas Asselin, 2020 Ni Romain, ni Arabe, Moundar bar Hareth, roi des Tayyés. Quand l’Arabie était chrétienne Mémoire Nicolas Asselin Sous la direction de : Paul-Hubert Poirier, directeur de recherche Résumé Ce mémoire porte sur celui que nous avons cru être le dernier roi des Arabes chrétiens du territoire romain, Moundar bar Hareth. En cours de route, nous avons redécouvert le dernier roi des Tayyés romains, un peuple oublié, dont l’histoire est essentielle pour bien comprendre les débuts de l’islam. À partir des œuvres des chroniqueurs syriaques, plus particulièrement de l’histoire de Jean d’Amida, nous avons remonté la piste afin de comprendre l’importance du dernier monarque de la famille de Gabala. Via cet examen des sources, nous analyserons également le corpus grec et arabe pour saisir les aléas de ce peuple d’Arabie, entraînant au passage, la redécouverte d’une polémique intra-chrétienne très ancienne, l’ismaélisme. L’ensemble de cette recherche se veut une étude originale et novatrice des événements entourant la fin de l’alliance traditionnelle entre les Romains et les Tayyés, une histoire singulière pavée de trahisons et d’une crise religieuse insoupçonnée. Ni Romain, ni Arabe, Moundar bar Hareth est figure incontournable du 6e siècle de notre ère. Le présent travail se propose d’analyser le règne du grand roi, plus particulièrement de son aspect religieux, et se divise en quatre parties, les deux premières portant sur les appellations anciennes et la redécouverte du peuple Tayyé. -

Assad Addresses the Chemical Weapons Issue

Assad Addresses the Chemical Weapons Issue by Lt. Col. (res.) Dr. Dany Shoham BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 879, July 1, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: In an unprecedented television interview on May 30, Syrian President Bashar Assad made detailed comments about his army’s alleged non-use of chemical weapons (CW). Referring to the (confirmed) employment of chemical weapons in Douma on April 7 and the subsequent US-British-French retaliatory raid, Assad claimed that CW had not been used by anyone (rather than by the rebels, as is usually contended). On May 30, 2018, Syrian President Bashar Assad participated in a televised interview on Russia Today in which he was asked about the regime’s use of chemical weapons (CW). In keeping with a lasting tradition whereby Assad laconically addresses the question of his army’s employment of such weapons, he tried to detail why such employment is implausible and to deny that his army is in fact in possession of CW. Given the regional and global significance of the lingering issue of CW use by his regime, it is worthwhile to take a close look at his words. Assad was asked in whose interest it was to gas opposition to the Syrian regime. He replied: “Is it in our interest? Why, and why now? Let alone that we don't have CW anyway, and we are not going to use it against our people. Our main battle was about winning the heart of civilians, and we won it. So how can you use CW against civilians you want to be supportive to you? “Second, let's suppose we have CW and want to use them. -

An Examination of the Potential Threat of a State-Sponsored Biological Attack Against the United States: a Study of Policy Implications

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2019 An Examination of the Potential Threat of a State-Sponsored Biological Attack Against the United States: A Study of Policy Implications Courtney Anne Pfluke Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Health Policy Commons, Other Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, and the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pfluke, Courtney Anne, "An Examination of the Potential Threat of a State-Sponsored Biological Attack Against the United States: A Study of Policy Implications" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3342. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3342 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

The Rule of Law: Retreat from Accountability

Research Report The Rule of Law: Retreat from Accountability “anasalhajj / Shutterstock.com” Executive Summary Schoolchildren stand on their destroyed school because of the war in the Yemeni city of Taiz Yemen / Taiz City. 2 November 2018 This is Security Council Report’s fifth research devastating conflicts of recent times, Council report on the rule of law. In it, we continue to members have–apart from general rhetoric–often explore the Security Council’s work in upholding ignored issues of accountability. individual criminal accountability as an aspect of The primacy of various national and regional 2019, No. 3 its rule of law agenda in the context of its primary interests evident in our four case studies cor- 23 December 2019 responsibility for maintaining international peace relates with Council members’ inconsistent This report is available online at securitycouncilreport.org. and security. Through an examination of four situ- upholding of accountability when political alli- ations the Council deals with regularly—Myanmar, ances are at stake. It may also be part of a wider For daily insights by SCR on evolving Security Council actions please Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen—the research report trend in the Council of reduced commitment subscribe to our “What’s In Blue” takes stock of and assesses the Council’s current towards ending impunity. series at whatsinblue.org or follow @SCRtweets on Twitter. attitude and actions in respect of accountability. In previous years, Council members have at The report shows that in some of the most times demonstrated their ability to rise above Security Council Report Research Report Decembert 2019 securitycouncilreport.org 1 Executive Summary their disagreements in order to adopt practi- cooperate with international criminal mech- 1 Executive Summary cal measures to advance accountability. -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 (MRG)

State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 Events of 2015 Focus on culture and heritage State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20161 Events of 2015 Front cover: Cholitas, indigenous Bolivian Focus on culture and heritage women, dancing on the streets of La Paz as part of a fiesta celebrating Mother’s Day. REUTERS/ David Mercado. Inside front cover: Street theatre performance in the Dominican Republic. From 2013 to 2016 MRG ran a street theatre programme to challenge discrimination against Dominicans of Haitian Descent in the Acknowledgements Dominican Republic. MUDHA. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Inside back cover: Maasai community members in gratefully acknowledges the support of all Kenya. MRG. organizations and individuals who gave financial and other assistance to this publication, including the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. © Minority Rights Group International, July 2016. All rights reserved. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non-commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for Support our work commercial purposes without the prior express Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate permission of the copyright holders. MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals to help us secure the rights of For further information please contact MRG. A CIP minorities and indigenous peoples around the catalogue record of this publication is available from world. All donations received contribute directly to the British Library. our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. ISBN 978-1-907919-80-0 Subscribe to our publications at State of www.minorityrights.org/publications Published: July 2016 Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe Lead reviewer: Carl Soderbergh to our publications, which offer a compelling Production: Jasmin Qureshi analysis of minority and indigenous issues and theWorld’s Copy editing: Sophie Richmond original research. -

United Nations Security Council

CAIMUN 2021 United Nations Security Council Background Guide A CANADA INTERNATIONAL MODEL UNITED NATIONS Tenth Annual Session | May 28-30, 2021 Dear Delegates, Othman Mekhlouf My name is Emily Ni, and it is my utmost pleasure to welcome you Secretary-General to the United Nations Security Council at Canada International Model United Nations 2021. Five years ago, I stumbled into the esoteric world of Model UN with the Angel Yuan intent of seeking academic enrichment. Twenty conferences later, at the Director-General end of this long journey, I can confdently say that the impact that Model UN has had on my life extends far beyond any intellectual beneft. Now, Nikki Wu I can only hope to instill the same passion in you, the delegate, as my Chief of Staff directors did for me. Cherish the memories you make as a delegate, and learn today so that you may lead tomorrow. Alongside me, Betty Pan will be serving as your Chair. Betty is a senior Matthew Leung Director of Logistics at West Point Grey Academy and is equally as excited to witness a weekend of riveting debate. Together, we look forward to welcoming you virtually come May! Madeline Kim USG of General Assemblies CAIMUN prides itself on its high level of educational discourse and professionalism. In the United Nations Security Council, delegates should come prepared with a comprehensive understanding of their Mikael Borres committee’s mandate, the topic at hand, and their country’s foreign USG of Specialized Agencies policy. These topics require thorough research and knowledge to allow for constructive debate; your work as a delegate will not only beneft Alec Yang yourself, but the committee as a whole. -

United States Foreign Policy Under President Donald Trump and the Fall of Islamic State in Syria

Economics And Social Sciences Academic Journal Vol.2, No.6; June- 2020 ISSN (5282 -0053); p –ISSN (4011 – 230X) UNITED STATES FOREIGN POLICY UNDER PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP AND THE FALL OF ISLAMIC STATE IN SYRIA 1Okey Oji Ph.D. and 2Raymond Adibe PhD 1Director of Research National Boundary Commission, Nigeria. 2Department of Political Science University of Nigeria ABSTRACT: The paper investigated the United States foreign policy and the fall of Islamic State (IS) in Syria. Specifically, it investigated if the non-prioritization of regime change by the Trump administration, and the consequent emphasis on US war against IS accounted for the fall of the terrorist group in Syria. Our findings revealed that the US interest in Syria under President Trump has been narrowed down to the war against terror, particularly the IS terrorist group. The US government under President Trump has shown little or no political will to commit US resources to ending. With President Trump administration’s refusal to fund anti-Assad rebel groups fighting the government, it severely weakened such groups and provided the Syrian government a huge opportunity to concentrate in battling IS to reclaim its territories. The paper relied on documentary data. It recommends the need to find a political solution to the crisis in Syria since it was what provided the avenue for IS to thrive in the first instance. As long as the civil war in Syria persists, the country will remain vulnerable to the possibility of terrorist groups operating from its territory. Keywords: United States, Foreign Policy, Syrian Conflict, Islamic State and Regime Change INTRODUCTION Senate. -

The CIA on Trial

The Management of Savagery The Management of Savagery How America’s National Security State Fueled the Rise of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and Donald Trump Max Blumenthal First published in English by Verso 2019 © Max Blumenthal 2019 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-229-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-743-2 (EXPORT) ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-228-4 (US EBK) ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-227-7 (UK EBK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, UK Let’s remember here, the people we are fighting today, we funded twenty years ago, and we did it because we were locked in this struggle with the Soviet Union … There’s a very strong argument, which is—it wasn’t a bad investment to end the Soviet Union, but let’s be careful what we sow because we will harvest. —Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to the House Appropriations Committee, April 23, 2009 AQ [Al Qaeda] is on our side in Syria. —Jake Sullivan in February 12, 2012, email to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton We underscore that states that sponsor terrorism risk falling victim to the evil they promote. -

SYRIA's SALAFI INSURGENTS: the Rise of the Syrian Islamic Front

Occasional #17 MARCH 2013 PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE UIpapers OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS. WWW.UI.SE SYRIA’S SALAFI INSURGENTS: THE RISE OF THE SYRIAN ISLAMIC FRONT In December 2012, eleven Syrian militant groups joined to form the Syrian Islamic Front, a powerful Islamist alliance. This report examines the structure of the Syrian insurgency, and the growing role of salafi factions within it. REPORT BY ARON LUND INDEX Introduction ...........................................................................................................3 Terminology ..........................................................................................................4 PART ONE: ISLAMISM IN SYRIA BEFORE THE UPRISING Salafism and salafi-jihadism .............................................................................5 Islamism in Syria before the uprising .............................................................7 Sectarian divisions in the Syrian revolution .................................................8 Social factors promoting the rise of salafism ..............................................9 Salafism as a response to the uprising .........................................................9 Structure of the Syrian insurgency .............................................................. 10 The rise and fall of the Free Syrian Army ...................................................11 Post-FSA bloc formation within the insurgency ...................................... 12 Salafi armed groups in Syria ........................................................................ -

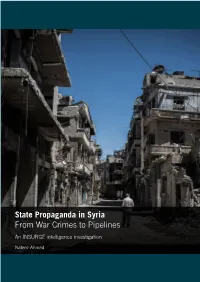

State Propaganda in Syria from War Crimes to Pipelines

STATE PROPAGANDA IN SYRIA: FROM WAR CRIMES TO PIPELINES IN SYRIA: FROM WAR PROPAGANDA STATE Published by: International State Crime Initiative School of Law Queen Mary University of London State Propaganda in Syria ISBN: 978-0-9934574-8-7 From War Crimes to Pipelines Nafeez Ahmed An INSURGE intelligence investigation School of Law Nafeez Ahmed (CC) Nafeez Ahmed 2018 This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International license: you may copy and distribute the document, only in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the authors and used for non-commercial, educational, or public policy purposes. ISBN: 978-0-9934574-8-7 (Paperback) and 978-0-9934574-9-4 (eBook-PDF) Published with the support of Forum for Change by: International State Crime Initiative School of Law Queen Mary University of London Mile End Road London E1 4NS United Kingdom www.statecrime.org Author: Nafeez Ahmed Recommended citation: Ahmed, N.(2018) State Propaganda in Syria: From War Crimes to Pipelines. London: International State Crime Initiative. Cover image: ‘Return to Homs’, A Syrian refugee walks among severely damaged buildings in downtown Homs, Syria, on June 3, 2014. (Xinhua/Pan Chaoyue) Layout and design: Paul Jacobs, QMUL CopyShop Printing: QMUL CopyShop School of Law From War Crimes to Pipelines ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 FOREWORD 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 1. INTRODUCTION 19 2. ESCALATION 23 2.1 OBSTRUCTION 24 2.2 JINGOISM 25 2.3 DUPLICITY 26 3. WHITE HELMETS 29 3.1 CAUGHT IN THE ACT 29 3.2 AID CONVOY CONTROVERSY 32 3.3 CHAIN OF CUSTODY 38 3.4 THE WHITE HELMETS AND PROPAGANDA: QUESTIONS 42 3.5 THE WHITE HELMETS AND PROPAGANDA: MYTHS 46 4.