Skin Bleaching in Jamaica: a Colonial Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2020Fall 2020

HarE JoHn HarE Students dressed is a freelance illustrator and in deep-sea diving graphic designer who works on Field Trip suits travel to the a range of projects. He lives in ocean deep in a yellow Gladstone, Missouri, with his submarine school bus. wife and two children. When they get there, they are introduced to creatures like T PRAISE FOR Field Trip to the Moon o luminescent squids and giant T he isopods, and discover an old ocean deep shipwreck. But when it’s time to return to the submarine bus, one student lingers to take a photo of a treasure chest and A Junior Library Guild Selection falls into a deep ravine. Luckily, A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year the child is entertained by a The Horn Book Fanfare List mysterious sea creature until ★ “Hare’s picture book debut is a winner . being retrieved by the teacher. A beautifully done wordless story about BOOKS FERGUSON MARGARET In his follow-up to Field Trip to a field trip to the moon with a sweet and funny alien encounter.”—School Library the Moon, John Hare’s rich, Journal, starred review atmospheric art in this wordless “[An] auspicious debut presents a world picture book invites children where a yellow crayon box shines Holiday House to imagine themselves in the like a beacon.”—Booklist story—a story full of surprises. MARGARET FERGUSON BOOKS BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE US $17.99$17.99 / CAN / CAN $23.99 $23.99 ISBN: 978-0-8234-4630-8 Holiday House Publishing, Inc. 5 1 7 9 9 HolidayHouse.com EAN Fall 2020 Printed in China 9 780823 446308 0408 Reinforced Illustration © 2020 by John Hare from Field Trip to the Ocean Deep HOLIDAY HOUSE Apples Gail Gibbons Summary Find out where your favorite crunchy, refreshing fruit comes from in this snack-sized book. -

Tarzan in the Early-20Th Century French Fantasy Landscape By

Wesleyan University The Honors College The Missing Link: Tarzan in the Early-20th Century French Fantasy Landscape by Medha Swaminathan Class of 2019 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in French Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Embracing the Invented in the “Benevolent” Colonial ................................................ 9 Imagining “Africa” ..................................................................................................... 19 Le Tour du Monde en Un Jour: Tarzan and the 1930s Paris Colonial Exhibitions .... 36 “Civilization” vs. “Civilized” vs. “Savage” ................................................................ 49 Homme Idéal or Missing Link? Fetish, Fascination, and Fear in French Eugenics ... 57 Sex, Youth, Beauty, Valor, and the Légionnaire ........................................................ 70 Saturnin Farandoul: Tarzan’s French Foil? ................................................................ 81 “Comment dit-on sites de rêve en anglais ?” .............................................................. 96 References ................................................................................................................. 100 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without an incredible amount -

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: Lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet Alexander B. Stohler FacultyAdviser: Dr, Dennis Klein r'^dw May 13,2020 )ol, Masters of Arts in Holocaust & Genocide Studies Kean University In partialfulfillumt of the rcquirementfar the degee of Moster of A* Abstract: I focused my research on modern, American hate groups. I found some criteria for early- warning signs of antisemitic, bigoted and genocidal activities. I included a summary of neo-Nazi and white supremacy groups in modern American and then moved to a more specific focus on contemporary and prominent groups like Atomwaffen Division, the Proud Boys, the Vinlanders Social Club, the Base, Rise Against Movement, the Hammerskins, and other prominent antisemitic and hate-driven groups. Trends of hate-speech, acts of vandalism and acts of violence within the past fifty years were examined. Also, how law enforcement and the legal system has responded to these activities has been included as well. The different methods these groups use for indoctrination of younger generations has been an important aspect of my research: the consistent use of hate-rock and how hate-groups have co-opted punk and hardcore music to further their ideology. Live-music concerts and festivals surrounding these types of bands and how hate-groups have used music as a means to fund their more violent activities have been crucial components of my research as well. The use of other forms of music and the reactions of non-hate-based artists are also included. The use of the internet, social media and other digital means has also be a primary point of discussion. -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

September-0Ctober 2013

september-0ctober 2013 On September 10, 1988, Museum of the As we enter our 25th anniversary year, I while doing the rounds through the Moving Image opened its doors to the can tell you that it has been a thrilling ride galleries, and then repair a video arcade public. At the time, years before the for the Museum, at least as action-packed game. He was a true professional, but will promise of the Internet and digital media as The Great Train Robbery. We have be best remembered as a great husband, were captured in the now-quaint phrase transformed and expanded over the years father, and friend, and he will be missed. “Information Superhighway,” the idea of a to serve a growing audience and to offer an We will pay tribute to Richie on October Museum, built on an historic site for movie increasingly ambitious slate of exhibitions, 4 at an event to mark the opening of a production, that would take a unified view screenings, and education programs. wonderful photo exhibit, The Booth, about of the disparate worlds of film, television, Our film programs range from the best projectionists and their workspaces. and video games, seemed as audacious as of classic Hollywood—as in our complete it was unprecedented. There was, simply, Howard Hawks retrospective—to the best Richie was a great showman; more than no museum like it in the world. It was an of contemporary world cinema—as in our anything at the Museum, he was obsessed innovative blend of a science museum, focus on the great French director Claire with making sure that we put on the best an art museum, a technology museum, Denis. -

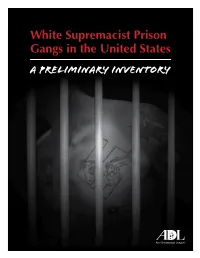

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States a Preliminary Inventory Introduction

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States A Preliminary Inventory Introduction With rising numbers and an increasing geographical spread, for some years white supremacist prison gangs have constitut- ed the fastest-growing segment of the white supremacist movement in the United States. While some other segments, such as neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, have suffered stagnation or even decline, white supremacist prison gangs have steadily been growing in numbers and reach, accompanied by a related rise in crime and violence. What is more, though they are called “prison gangs,” gangs like the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, Aryan Circle, European Kindred and others, are just as active on the streets of America as they are behind bars. They plague not simply other inmates, but also local communities across the United States, from California to New Hampshire, Washington to Florida. For example, between 2000 and 2015, one single white supremacist prison gang, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, was responsible for at least 33 murders in communities across Texas. Behind these killings were a variety of motivations, including traditional criminal motives, gang-related murders, internal killings of suspected informants or rules-breakers, and hate-related motives directed against minorities. These murders didn’t take place behind bars—they occurred in the streets, homes and businesses of cities and towns across the Lone Star State. When people hear the term “prison gang,” they often assume that such gang members plague only other prisoners, or perhaps also corrections personnel. They certainly do represent a threat to inmates, many of whom have fallen prey to their violent attacks. -

Universiv Micrcsilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tlie sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

Inside Subculture the Postmodern Meaning of Style

Inside Subculture The Postmodern Meaning of Style David Muggleton OXFORD Inside Subculture Dress, Body, Culture Series Editor Joanne B. Eicher, Regents’ Professor, University of Minnesota Advisory Board: Ruth Barnes, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford Helen Callaway, CCCRW, University of Oxford James Hall, University of Illinois at Chicago Beatrice Medicine, California State University, Northridge Ted Polhemus, Curator, “Street Style” Exhibition, Victoria & Albert Museum Griselda Pollock, University of Leeds Valerie Steele, The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology Lou Taylor, University of Brighton John Wright, University of Minnesota Books in this provocative series seek to articulate the connections between culture and dress which is defined here in its broadest possible sense as any modification or supplement to the body. Interdisciplinary in approach, the series highlights the dialogue between identity and dress, cosmetics, coiffure, and body alterations as manifested in practices as varied as plastic surgery, tattooing, and ritual scarification. The series aims, in particular, to analyze the meaning of dress in relation to popular culture and gender issues and will include works grounded in anthropology, sociology, history, art history, literature, and folklore. ISSN: 1360-466X Previously published titles in the Series Helen Bradley Foster, “New Raiments of Self”: African American Clothing in the Antebellum South Claudine Griggs, S/he: Changing Sex and Changing Clothes Michaele Thurgood Haynes, Dressing Up Debutantes: Pageantry and Glitz in Texas Anne Brydon and Sandra Niesson, Consuming Fashion: Adorning the Transnational Body Dani Cavallaro and Alexandra Warwick, Fashioning the Frame: Boundaries, Dress and the Body Judith Perani and Norma H. Wolff, Cloth, Dress and Art Patronage in Africa Linda B. -

WHITE SUPREMACY a HISTORY of HATE White Supremacists

3/15/2017 WHITE SUPREMACY A HISTORY OF HATE Capt. Jason Wilke [email protected] 920-840-0943 White Supremacists Webster's Dictionary WHITE SUPREMACY WHITE SEPARATISM • Caucasians that feel • Do not preach they are they are superior to superior to other other racial races?? backgrounds. • Seek a separate nation • Identify with the for white people. struggle for existence • They claim that all and survival. races should live • the fittest “race”. segregated from one • Other races unable to another. support themselves. • Race mixing will eventually lead to the • Call for the extermination of other fall of the white race?? races! • Separation is the answer to all race issues. 1 3/15/2017 KU KLUX KLAN Greek – the Circle or Clan Pulaski Tennessee / 1865 Ku Klux Klan - KKK 3 WAVES OF THE KU KLUX KLAN 1st Wave 2nd Wave 3rd Wave • Founded by six • African Americans • approximately Confederate began to vote and 5,000 members soldiers – “moral even win elected nationwide. Booster” positions. • The Klan has • Col Nathan • Primarily directed branched out Bedford Forest - at African into several terrorism toward Americans and splinter cells Blacks “1st wave”. whites who opposed called • Robes and Hoods the klan. “Klaverns”. were used to hide • Civil right • President Barak identity – knight movement Obama has riders. ending Jim Crow spiked Klaverns Laws grown and numbers. 2 3/15/2017 SUPREME COURT FREEDOM OF SPEECH? THE KLAN TODAY?????? WISCONSIN HATE GROUPS 800+ KKK - Monroe National Socialist Aryan Nation - Appleton Hurley WI Movement - Milwaukee -

Skinheads Shaved for Battle: a Cultural History of American Skinheads

Jack B. Moore. Skinheads Shaved for Battle: A Cultural History of American Skinheads. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1993. 200 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-87972-582-2. Reviewed by Themis Chronopoulos Published on H-PCAACA (July, 1996) Contrary to other American media and anti- The greatest weakness of the book is Moore's racist organization accounts, this study argues painstaking attempt to portray the entire skin‐ that the Skinhead movement is a cultural rather head movement as predominantly racist and fas‐ than a political phenomenon. It attempts to trace cist since its inception. It is doubtful that the ma‐ the skinhead cult from its onset but focuses on jority of skinheads during any period of their exis‐ fascist American skinheads in the 1980s, the frst tence outside the United States were either fascist decade of their development as a separate and or racist. In late 1960s Britain, the skinhead move‐ identifiable group. ment was a multiracial working-class phenome‐ Using reports by the Anti-Defamation League, non with Jamaican reggae and ska as well as the Southern Poverty Law Center, newspaper arti‐ American soul functioning as its most important cles, and skinheads themselves, Jack Moore pro‐ cultural objectifications; Moore's assertion that vides an articulate cultural portrait of fascist skin‐ this lasted for only a few months is incorrect, for heads, their links to white supremacist groups, in fact, it continued well into the 1970s; indeed, and their violent excursions--many of which re‐ the skinheads were very influential in the revival sulted to the death of innocent people.