Southeast Asia Research Centre (SEARC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nights Underground in Darkest London: the Blitz, 1940–1941

Nights Underground in Darkest London: The Blitz, 1940–1941 Geoffrey Field Purchase College, SUNY After the tragic events of September 11, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani at once saw parallels in the London Blitz, the German air campaign launched against the British capital between September 1940 and May 1941. In the early press con- ferences at Ground Zero he repeatedly compared the bravery and resourceful- ness of New Yorkers and Londoners, their heightened sense of community forged by danger, and the surge of patriotism as a town and its population came to symbolize a nation embattled. His words had immediate resonance, despite vast differences between the two situations. One reason for the Mayor’s turn of mind was explicit: he happened at that moment to be reading John Lukacs’ Five Days in London, although the book examines the British Cabinet’s response to the German invasion of France some months before bombing of the city got un- derway. Without doubt Tony Blair’s outspoken support for the United States and his swift (and solitary) endorsement of joint military action also reinforced this mental coupling of London and New York. But the historical parallel, however imperfect, seemed to have deeper appeal. Soon after George W. Bush was telling visitors of his admiration for Winston Churchill, his speeches began to emulate Churchillian cadences, Karl Rove hung a poster of Churchill in the Old Execu- tive Office Building, and the Oval Office sported a bronze bust of the Prime Min- ister, loaned by British government.1 Clearly Churchill, a leader locked in conflict with a fascist and a fanatic, was the man for this season, someone whom all political parties could invoke and quote, someone who endured and won in the end. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020 The Dissertation Committee for John Michael Meyer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation. One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) Committee: Ami Pedahzur, Supervisor Zoltan D. Barany David M. Buss William Roger Louis Thomas G. Palaima Paul B. Woodruff One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) by John Michael Meyer Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis who guided me on this endeavor from start to finish and To Lorna Paterson Wingate Smith. Acknowledgements Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis have helped me immeasurably throughout my time at the University of Texas, and I wish that everyone could benefit from teachers so rigorous and open minded. I will never forget the compassion and strength that they demonstrated over the course of this project. Zoltan Barany developed my skills as a teacher, and provided a thoughtful reading of my first peer-reviewed article. David M. Buss kept an open mind when I approached him about this interdisciplinary project, and has remained a model of patience while I worked towards its completion. My work with Tom Palaima and Paul Woodruff began with collaboration, and then moved to friendship. Inevitably, I became their student, though they had been teaching me all along. -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 Free

FREE CHARLEYS WAR: 1 AUGUST-17 OCTOBER 1916 PDF Pat Mills,Joe Colquhoun | 112 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781840239294 | English | London, United Kingdom Charley's War - Wikipedia This book picks up where the last left off with two main story arcs. The first follows the technological innovation theme from the earlier book and examines the impact of the introduction of the first British tanks on the battle. The second half sees the Germans reacting to this new development in the only way they can — increased ferocity, brutality and dirty tactics — flying in the face Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 the gentlemanly conduct of previous confrontations run by unsuitable aristocrats. The other major theme running through this book is the regularlity with which the British army is willing to shoot and torture its own men, for anything from basic insubordination through to falling asleep on duty. As before, the waste of human life presented Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 the comic is poignant and more than a little shocking, not least of all because the story is reprinted from a publication aimed at young boys interested in the glamour of soldiering. Charley loses friends quicker than he can make them and the horror of it all turns this social, caring individual away from forming any bonds with his colleagues in the trenches because the likelihood of losing them is so high. When all the English look like bedraggled waifs and the Germans like uniformed barbarians, it Charleys War: 1 August-17 October 1916 us away from the true nature World War I — an entire generation of men grinding one another into mince. -

Fall 2020Fall 2020

HarE JoHn HarE Students dressed is a freelance illustrator and in deep-sea diving graphic designer who works on Field Trip suits travel to the a range of projects. He lives in ocean deep in a yellow Gladstone, Missouri, with his submarine school bus. wife and two children. When they get there, they are introduced to creatures like T PRAISE FOR Field Trip to the Moon o luminescent squids and giant T he isopods, and discover an old ocean deep shipwreck. But when it’s time to return to the submarine bus, one student lingers to take a photo of a treasure chest and A Junior Library Guild Selection falls into a deep ravine. Luckily, A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year the child is entertained by a The Horn Book Fanfare List mysterious sea creature until ★ “Hare’s picture book debut is a winner . being retrieved by the teacher. A beautifully done wordless story about BOOKS FERGUSON MARGARET In his follow-up to Field Trip to a field trip to the moon with a sweet and funny alien encounter.”—School Library the Moon, John Hare’s rich, Journal, starred review atmospheric art in this wordless “[An] auspicious debut presents a world picture book invites children where a yellow crayon box shines Holiday House to imagine themselves in the like a beacon.”—Booklist story—a story full of surprises. MARGARET FERGUSON BOOKS BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE US $17.99$17.99 / CAN / CAN $23.99 $23.99 ISBN: 978-0-8234-4630-8 Holiday House Publishing, Inc. 5 1 7 9 9 HolidayHouse.com EAN Fall 2020 Printed in China 9 780823 446308 0408 Reinforced Illustration © 2020 by John Hare from Field Trip to the Ocean Deep HOLIDAY HOUSE Apples Gail Gibbons Summary Find out where your favorite crunchy, refreshing fruit comes from in this snack-sized book. -

Tarzan in the Early-20Th Century French Fantasy Landscape By

Wesleyan University The Honors College The Missing Link: Tarzan in the Early-20th Century French Fantasy Landscape by Medha Swaminathan Class of 2019 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in French Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Embracing the Invented in the “Benevolent” Colonial ................................................ 9 Imagining “Africa” ..................................................................................................... 19 Le Tour du Monde en Un Jour: Tarzan and the 1930s Paris Colonial Exhibitions .... 36 “Civilization” vs. “Civilized” vs. “Savage” ................................................................ 49 Homme Idéal or Missing Link? Fetish, Fascination, and Fear in French Eugenics ... 57 Sex, Youth, Beauty, Valor, and the Légionnaire ........................................................ 70 Saturnin Farandoul: Tarzan’s French Foil? ................................................................ 81 “Comment dit-on sites de rêve en anglais ?” .............................................................. 96 References ................................................................................................................. 100 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without an incredible amount -

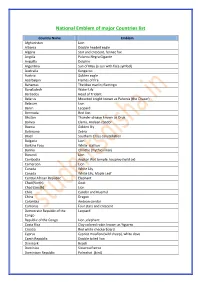

National Emblem of Major Countries List

National Emblem of major Countries list Country Name Emblem Afghanistan Lion Albania Double headed eagle Algeria Star and crescent, fennec fox Angola Palanca Negra Gigante Anguilla Dolphin Argentina Sun of May (a sun with face symbol) Australia Kangaroo Austria Golden eagle Azerbaijan Flames of fire Bahamas The blue marlin; flamingo Bangladesh Water Lily Barbados Head of Trident Belarus Mounted knight known as Pahonia (the Chaser) Belgium Lion Benin Leopard Bermuda Red lion Bhutan Thunder dragon known as Druk Bolivia Llama, Andean condor Bosnia Golden lily Botswana Zebra Brazil Southern Cross constellation Bulgaria Lion Burkina Faso White stallion Burma Chinthe (mythical lion) Burundi Lion Cambodia Angkor Wat temple, kouprey (wild ox) Cameroon Lion Canada White Lily Canada White Lily, Maple Leaf Central African Republic Elephant Chad(North) Goat Chad (South) Lion Chile Candor and Huemul China Dragon Colombia Andean condor Comoros Four stars and crescent Democratic Republic of the Leopard Congo Republic of the Congo Lion ,elephant Costa Rica Clay colored robin known as Yiguirro Croatia Red white checkerboard Cyprus Cypriot mouflon (wild sheep), white dove Czech Republic Double tailed lion Denmark Beach Dominica Sisserou Parrot Dominican Republic Palmchat (bird) Ecuador Andean condor Egypt Golden eagle Equatorial Guinea Silk cotton tree Eritrea Camel Estonia Barn swallow, cornflower Ethiopia Abyssinian lion European Union A circle of 12 stars Finland Lion France Lily Gabon Black panther Gambia Lion Georgia Saint George, lion Germany Corn -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................ -

University of Mandalay Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 Tint Lwin

University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS Tint Lwin Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS A Dissertation submitted to University of Mandalay in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History Department of History Tint Lwin 4 Ph.D/Hist.-3 Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS By Tint Lwin, B.A(Hist:), M.A. 4 Ph.D./Hist.-3 (2006-07) This Dissertation is submitted to the Board of Examiners In History, University of Mandalay in Candidature For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved External Examiner, Referee Supervisor Member Member Co-Supervisor Chairperson Abstract In writing this dissertation on the "Art and Architecture in Pakhangyi during the monarchical days", every conceivable aspect has been covered, and the dissertation is divided into four chapters. In writing the First Chapter, the artifacts and implements of Neolithic age period, the religious edifices and wall paintings are mainly used as evidences to show the development of Pakhangyi region as one of the main centres of Myanmar civilization other than Bagan and other places of cultural interest. The First Chapter asserts the historical and cultural legitimacy of the Pakhangyi region by presenting its visible facets of successive periods starting from the stone age: stone implements, how the very term Pakhangyi emerge, the oldest villages, the massive city wall, how the city was rebuilt five times, the quality of bricks used and the pattern of brick bonding, water supply system, agriculture and the region’s inhabitants. -

Viewees Who Donated Their Time and Knowledge to the Dissertation Research

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Selling Sacred Cities: Tourism, Region, and Nation in Cusco, Peru A Dissertation Presented by Mark Charles Rice to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Mark Rice 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Mark Charles Rice We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Paul Gootenberg – Dissertation Advisor SUNY Distinguished Professor, History, Stony Brook University Eric Zolov – Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, History, Stony Brook University Brooke Larson Professor, History, Stony Brook University Deborah Poole Professor, Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Selling Sacred Cities: Tourism, Region, and Nation in Cusco, Peru by Mark Charles Rice Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2014 It is hard to imagine a more iconic representation of Peru than the Inca archeological complex of Machu Picchu located in the Cusco region. However, when US explorer, Hiram Bingham, announced that he had discovered the “lost city” in 1911, few would have predicted Machu Picchu’s rise to fame during the twentieth century. My dissertation traces the unlikely transformation of Machu Picchu into its present-day role as a modern tourism destination and a representation of Peruvian national identity.