1864 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Western Railway Ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway Ships from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

5/20/2011 Great Western Railway ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway ships From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Great Western Railway’s ships operated in Great Western Railway connection with the company's trains to provide services to (shipping services) Ireland, the Channel Islands and France.[1] Powers were granted by Act of Parliament for the Great Western Railway (GWR) to operate ships in 1871. The following year the company took over the ships operated by Ford and Jackson on the route between Wales and Ireland. Services were operated between Weymouth, the Channel Islands and France on the former Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company routes. Smaller GWR vessels were also used as tenders at Plymouth and on ferry routes on the River Severn and River Dart. The railway also operated tugs and other craft at their docks in Wales and South West England. The Great Western Railway’s principal routes and docks Contents Predecessor Ford and Jackson Successor British Railways 1 History 2 Sea-going ships Founded 1871 2.1 A to G Defunct 1948 2.2 H to O Headquarters Milford/Fishguard, Wales 2.3 P to R 2.4 S Parent Great Western Railway 2.5 T to Z 3 River ferries 4 Tugs and work boats 4.1 A to M 4.2 N to Z 5 Colours 6 References History Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the GWR’s chief engineer, envisaged the railway linking London with the United States of America. He was responsible for designing three large ships, the SS Great Western (1837), SS Great Britain (1843; now preserved at Bristol), and SS Great Eastern (1858). -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

Just a Balloon Report Jan 2017

Just a Balloon BALLOON DEBRIS ON CORNISH BEACHES Cornish Plastic Pollution Coalition | January 2017 BACKGROUND This report has been compiled by the Cornish Plastic Pollution Coalition (CPPC), a sub-group of the Your Shore Network (set up and supported by Cornwall Wildlife Trust). The aim of the evidence presented here is to assist Cornwall Council’s Environment Service with the pursuit of a Public Spaces Protection Order preventing Balloon and Chinese Lantern releases in the Duchy. METHODOLOGY During the time period July to December 2016, evidence relating to balloon debris found on Cornish beaches was collected by the CPPC. This evidence came directly to the CPPC from members (voluntary groups and individuals) who took part in beach-cleans or litter-picks, and was accepted in a variety of formats:- − Physical balloon debris (latex, mylar, cords & strings, plastic ends/sticks) − Photographs − Numerical data − E mails − Phone calls/text messages − Social media posts & direct messages Each piece of separate balloon debris was logged, but no ‘double-counting’ took place i.e. if a balloon was found still attached to its cord, or plastic end, it was recorded as a single piece of debris. PAGE 1 RESULTS During the six month reporting period balloon debris was found and recorded during beach cleans at 39 locations across Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly shown here:- Cornwall has an extensive network of volunteer beach cleaners and beach cleaning groups. Many of these are active on a weekly or even daily basis, and so some of the locations were cleaned on more than one occasion during the period, whilst others only once. -

DR. BORLASE's ACCOUNT of LUDGVAN by P

DR. BORLASE'S ACCOUNT OF LUDGVAN By P. A. S. POOL, M.A. (Gwas Galva) R. WILLIAM BORLASE at one time intended to write a D parochial history of Cornwall, and for that purpose collected a large MS. volume of Parochial Memoranda, which is now pre• served at the British Museum (Egerton MSS. 2657). Although of great interest and importance, this consists merely of disjointed notes and is in no sense a finished product. But among Borlase's MSS. at the Penzance Library is a systematic and detailed account, compiled in 1770, of the parish of Ludgvan, of which he was Rector from 1722 until his death in 1772. This has never been published, and the present article gives a summary of its contents, with extracts. The account starts with a discussion of the derivation of the parish name, Borlase doubting the common supposition " that a native saint by his holiness and miracles distinguished it from other districts by his own celebrated name," and concluding that " the existence of such a person as St. Ludgvan . may well be accounted groundless." His own view was that the parish was called after the Manor of Ludgvan, which in turn derived its name from the Lyd or Lid, the name given in Harrison's Description of Britain (1577) to the stream running through the parish. It is noteworthy that the older Ludgvan people still, at the present day, pronounce the name " Lidjan." Borlase next gives the descent of the manor, the Domesday LUDUAM, through the families of Ferrers, Champernowne, Brook, Blount and Paulet. -

St Mawes to Cremyll Overview to Natural England’S Compendium of Statutory Reports to the Secretary of State for This Stretch of Coast

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: St Mawes to Cremyll Overview to Natural England’s compendium of statutory reports to the Secretary of State for this stretch of coast 1 England Coast Path | St Mawes to Cremyll | Overview Map A: Key Map – St Mawes to Cremyll 2 England Coast Path | St Mawes to Cremyll | Overview Report number and title SMC 1 St Mawes to Nare Head (Maps SMC 1a to SMC 1i) SMC 2 Nare Head to Dodman Point (Maps SMC 2a to SMC 2h) SMC 3 Dodman Point to Drennick (Maps SMC 3a to SMC 3h) SMC 4 Drennick to Fowey (Maps SMC 4a to SMC 4j) SMC 5 Fowey to Polperro (Maps SMC 5a to SMC 5f) SMC 6 Polperro to Seaton (Maps SMC 6a to SMC 6g) SMC 7 Seaton to Rame Head (Maps SMC 7a to SMC 7j) SMC 8 Rame Head to Cremyll (Maps SMC 8a to SMC 8f) Using Key Map Map A (opposite) shows the whole of the St Mawes to Cremyll stretch divided into shorter numbered lengths of coast. Each number on Map A corresponds to the report which relates to that length of coast. To find our proposals for a particular place, find the place on Map A and note the number of the report which includes it. If you are interested in an area which crosses the boundary between two reports, please read the relevant parts of both reports. Printing If printing, please note that the maps which accompany reports SMC 1 to SMC 8 should ideally be printed on A3 paper. -

Muttons Cottage, Dinhams Bridge, St Mabyn, Bodmin

MUTTONS COTTAGE, DINHAMS BRIDGE, ST MABYN, BODMIN, CORNWALL MUTTONS COTTAGE, DINHAMS BRIDGE, ST MABYN, BODMIN, CORNWALL PL30 3BP A secluded three bedroom cottage situated in a wooded valley beside the River Allen in North Cornwall. A secluded three bedroom cottage situated in of Wadebridge, take the fourth exit onto the A39 Family Bathroom a wooded valley beside the River Allen in North eastbound signposted for Bude and Camelford. With white ceramic bath, hand basin, and W.C. Dual Cornwall. The property benefits from valley and river function bath tap with flexible metal hose connected views, lawn, vegetable garden, ample parking and oil Follow the A39 east for approximately 2 miles from to wall mounted shower head. Radiator. Door to fired central heating the roundabout, and at the second crossroads take Hallway. the right turn signposted “St Mabyn 1½“ (opposite a St Mabyn: 1 mile, Wadebridge: 4 miles, Bodmin: 7 miles. turning signposted to St Endellion). Dining Room: 3.92m x 3.62m (12’10” x 11’11”) max dims General Description Follow the road down to the bottom of the hill and Timber floorboards and beamed ceiling. Dual aspect Muttons Cottage is situated in a quiet rural location take the first turning on the right, without crossing room with sash window. Former solid fuel Rayburn, beside the River Allen within a wooded valley, the river. Follow this minor road for approximately 150 now redundant. Radiator. BT Socket. 3 twin plug approximately 1 mile from the centre of the village of yards and you will find the gateway to the entrance sockets. -

Environment Agency Plan

environment agency plan FAL AND ST AUSTELL STREAMS SECOND ANNUAL REVIEW JULY 2000 Fal &t St Austell Streams 2"" Annual Review Further copies of this Annual Review can be obtained from: Team Leader, LEAPs Environment Agency Sir John Moore House Victoria Square Bodmin PL31 1EB Tel: 01208 78301 Fax: 01208 78321 E n v i r o n m e n t A g e n c y Information Services Unit Please return or renew this item by the due date Due Date 21 ' N > C \) - 06 Environment Agency Copyright Waiver This report is Intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced In any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement Is given to the Environment Agency. Note: This Is not a legally or scientifically binding document. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY n i i i i i i i i 108444 Fal & St Austell Streams 2* Annual Review Our Vision Our vision is of this area being managed in a sustainable way, that balances the needs of all users with the needs of the environment. We look forward to a future where a healthy economy leads to: Biodiversity and the physical habitat for wildlife being enhanced People's enjoyment and appreciation of the environment continuing to grow Pressures from human wants being satisfied sustainably Foreword This is the second annual review of the Fal and St.Austell Streams Action Plan, which was published in December 1997. It describes the progress that has been made since. In addition to our own actions in the plan area we welcome opportunities to work in partnership with other groups. -

202 Meeting of Truro City Council Held on Monday 23

MEETING OF TRURO CITY COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY 23 APRIL 2018 at 7.00 pm PRESENT: The Mayor (Councillor J Tamblyn) Councillors Allen, Biscoe, Butler, Mrs Callen, Mrs Cox, Mrs Eathorne-Gibbons, Ellis, Rich, Roden, Smith, Ms Southcombe, Mrs Stokes, Mrs Tudor, Webb, Vella, Wells and Wilson APOLOGIES: Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Councillors Mrs Carlyon, Jones, Miss Jones, Mrs Neale, Nolan and Mrs Nolan Also in Attendance: Mr David Harris CC & Mr Michael Eathorne-Gibbons CC Mr Peter Bailey, Resident, who audio-recorded the meeting PRAYERS Prior to the formal business of the Council, due to apologies from the Mayor’s Chaplain, the Reverend Christopher Epps, the Mayor of Truro said prayers. 421 DISCLOSURE OR DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS There were no disclosures or declarations of interest to report. 422 CORNWALL COUNCIL (F1) (i) Stadium for Cornwall Councillor Harris commented on Cornwall Council’s approval for the Stadium of Cornwall to go ahead, making it clear that the resolution contained the point that there would be no payment to Inox as a result of the stadium being built. (ii) Malpas Marine Councillor Rich commented that Malpas Marine had recently been on the market. The Port of Truro borrowed money from Cornwall Council to purchase the marine (at no extra cost to taxpayers), making it an official part of the Port of Truro, which ferry companies frequently used to land. The site included a workshop, slipway and yard. Consideration was now being given to have a café on the site to generate income towards paying off the loan. -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes

1859 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .............................................................................................................................. 24 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 42 4. Midsummer Sessions 1859 ...................................................................................................... 51 5. Summer Assizes ....................................................................................................................... 76 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................. 116 ========== Royal Cornwall Gazette, Friday January 7, 1859 1. Epiphany Sessions These sessions opened at the County Hall, Bodmin, on Tuesday the 4th inst., before the following Magistrates:— Sir Colman Rashleigh, Bart., John Jope Rogers, Esq., Chairmen. C. B. Graves Sawle, Esq., Lord Vivian. Thomas Hext, Esq. Hon. G.M. Fortescue. F.M. Williams, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. H. Thomson, Esq. T. J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. J. P. Magor, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. R. G. Bennet, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. Thomas Paynter, Esq. J. King Lethbridge, Esq. R. G. Lakes, Esq. W. H. Pole Carew, Esq. J. T. H. Peter, Esq. J. Tremayne, Esq. C. A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, -

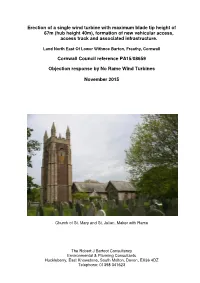

Erection of a Single Wind Turbine with Maximum Blade Tip Height of 67M (Hub Height 40M), Formation of New Vehicular Access, Access Track and Associated Infrastructure

Erection of a single wind turbine with maximum blade tip height of 67m (hub height 40m), formation of new vehicular access, access track and associated infrastructure. Land North East Of Lower Withnoe Barton, Freathy, Cornwall Cornwall Council reference PA15/08659 Objection response by No Rame Wind Turbines November 2015 Church of St. Mary and St. Julian, Maker with Rame The Robert J Barfoot Consultancy Environmental & Planning Consultants Huckleberry, East Knowstone, South Molton, Devon, EX36 4DZ Telephone: 01398 341623 Contents Introduction and background Page 1 Executive Summary Page 2 The flawed pre-application public consultation Page 6 The Written Ministerial Statement of 18 June 2015 Page 9 Landscape and visual Impacts Page 11 Shadow flicker/shadow throw Page 25 Impacts on heritage assets Page 27 Effects on tourism Page 34 Ecology issues Page 35 Noise issues Page 38 Community Benefit Page 44 The benefits of the proposal Page 46 The need for the proposal Page 51 Planning policy Page 55 Conclusions Page 62 Appendices Appendix 1 Relevant extracts from the Trenithon Farm appeal statement Appendix 2 Letter from Cornwall Council – Trenithon Farm appeal invalid Appendix 3 Tredinnick Farm Consent Order Appendix 4 Tredinnick Farm Statement of Facts and Grounds Appendix 5 Decision Notice for Higher Tremail Farm Appendix 6 Gerber High Court Judgement Appendix 7 Shadow Flicker Plan with landowner’s boundaries Appendix 8 Lower Torfrey Farm Consent Order Appendix 9 Smeather’s Farm Consent Order Appendix 10 English Heritage recommendations Appendix 11 Review by Dr Tim Reed Appendix 12 Email circulated by the PPS to the Prime Minister Appendix 13 Letter from Ed Davey to Mary Creagh MP Appendix 14 Letter from Phil Mason to Stephen Gilbert MP 1 Introduction and background 1.1 I was commissioned by No Rame Wind Turbines (NRWT) to produce a response to the application to erect a wind turbine at land north east of Lower Withnoe Barton, Freathy, Cornwall, commonly known as the Bridgemoor turbine.