Guide to the Japanese Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor

Samsuddin M. F., Hamzah A. H., & Mohd Radzi F. dealogy Journal, 2020 Vol. 5, No. 2, 79-88 Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor Muhammad Fitri Samsuddin1, Azni Hanim Hamzah2, Fazlina Mohd Radzi3, Siti Nurul Akma Ahmad4, Mohd Faizul Noorizan6, Mohd Ali Azraie Bebit6 12356Faculty of Art & Design, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka 4Faculty of Business & Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka Authors’ email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Published: 28 September 2020 ABSTRACT Malaysian textile motifs especially the Batik motifs and its product are highly potential to sustain in a global market. The integration of intercultural design of Malaysian textile motifs and Japanese textile motifs will further facilitate both textile industries to be sustained and demanded globally. Besides, Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs can be creatively design on other platforms not limited to the clothes. Therefore, this study is carried out with the aim of integrating the Malaysian textile motifs specifically focuses on batik motifs and Japanese textile motifs through product diversification. This study focuses on integrating both textile motifs and diversified the design on a home décor including wall frame, table clothes, table runner, bed sheets, lamp shades and other potential home accessories. In this concept paper, literature search was conducted to describe about the characteristics of both Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs and also to reveal insights about the practicality and the potential of combining these two worldwide known textile industries. The investigation was conducted to explore new pattern of the combined textiles motifs. -

The Influence of Japanese Textile Design on French Art Deco Textiles, 1920-1930

CREATING CLOTH, CREATING CULTURE: THE INFLUENCE OF JAPANESE TEXTILE DESIGN ON FRENCH ART DECO TEXTILES, 1920-1930 By SARA ELISABETH HAYDEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Apparel and Textiles WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Apparel, Merchandising, Design and Textiles AUGUST 2007 © Copyright by SARA ELISABETH HAYDEN, 2007 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by SARA ELISABETH HAYDEN, 2007 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of SARA ELISABETH HAYDEN find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Chair ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee, Linda B. Arthur, PhD, Patricia Fischer, MA and Dr. Lombuso Khoza, PhD for their continued support and guidance. I would like to extend special thanks to Dr. Arthur for her research assistance and mentoring throughout my graduate studies. Additionally, I am very grateful to have received the Hill Award administered through the Department of Apparel, Merchandising, Design and Textiles in the College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resource Sciences. Dr. Alberta Hill’s generous endowment of the Hill Award made my thesis research possible. iii CREATING CLOTH, CREATING CULTURE: THE INFLUENCE OF JAPANESE TEXTILE DESIGN ON FRENCH ART DECO TEXTILES, 1920-1930 Abstract by Sara Elisabeth Hayden, M.A. Washington State University August 2007 Chair: Linda B. Arthur After Japan opened its doors to international commerce in the 1850s, its trade with European countries blossomed. From the beginning of France’s economic interaction with Japan in the nineteenth century, these commercial transactions led to cultural exchange via trade wares, which included clothing and fabrics. -

Hand Evaluation and Formability of Japanese Traditional 'Chirimen' Fabrics

Chapter 11 Hand Evaluation and Formability of Japanese Traditional ‘Chirimen’ Fabrics Takako Inoue and Masako Niwa Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/48585 1. Introduction Clothes, which are used in direct contact with the human body, are mostly made of fabrics of planar fiber construction, that is, they are manufactured for the most part from textiles. Needless to say, the quality of clothes directly affects both the human mind and body. For this reason, it is essential to have a system which allows us to accurately and thoroughly evaluate the qualities and use-value of textiles. Since Prof. Sueo Kawabata of Kyoto University developed the KES (Kawabata Evaluation System) in 1972 (Kawabata, 1972), research into fabric handle and quality based on physical properties has made remarkable progress, and objective evaluation of fabrics using the KES system is now common around the world. Evaluation formulas for fabric formability, tailoring appearance, and hand evaluation of the tailored-type fabrics represented by those used in tailored men's suits have been created, and allow us to objectively evaluate the fundamental performance capabilities of fabrics, unaffected by changing times and fashions (Kawabata, 1980). Furthermore, fabric formability, tailoring appearance, hand evaluation, and quality of tailored-type fabrics can now be influenced at every stage, even the very earliest: at the fiber-to-yarn stage, the yarn- to-fabric stage, and then at all the subsequent stages, up to the finishing of the material. This is invaluable for the fabric design process (Kawabata et al., 1992). -

EVOLUTION of JAPANESE WOMEN's KIMONO from A.D. 200 to 1960

THE EVOUTCION OF JAPANESE WOMEN'S KIMONO FEOK A.D. 200 TO 1960 *"> MASAKO TOYOSHMA B. S., Fukuoka Women's University, 1963 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE General Home Economics College of Home Eoonomios KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1967 Approved byi Major Professor TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. HU-STYLE PERIOD (A.D. 200-552) 7 Political Situation 7 Dress of tha Period 9 III. T'ANG-STYLE PERIOD (552-894) 13 Politioal Situation 13 Dress of T'ang-stylo Period 18 IV. OS0DE-FASHI0N PERIOD (894-1477) 26 Political Situation 26 Dress of the OBode-Fashion Period 33 V. KOSODE-FASHION PERIOD (1477-1868) 44 Politioal Situation 44 Dress of Kosode-fashion Period •• 52 VI. JAPANESE-WESTERN PERIOD (1868-1960) 68 Politioal Situation 68 Dress of Japanese -'Western Period • 75 VII. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 83 Summary ............. 83 Recommendations •• •• 87 88 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • ii LIST OF PLATES PLATE PAGE I Dress of Hu-style Period ..... ... 11 II Dress of T'ang-style Period 21 III Dress of Osode-fashion Period 37 17 Dress of Kosode-fashion Period 54 V Dress of Japanese -We stern Period. ............ 82 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Costume expresses a relationship to the ideals and the spirit - of the country during a particular time. Hurlock states in The Psych ology of Pre s s : In every age, some ideal is developed which predominates over all others. This ideal may be religious or political; it may re- late to the crown or to the people; it may be purely social or artistic, conservative or radical. -

Japanese Design Motifs and Their Symbolism As Used On

JAPANESE DESIGN MOTIFS AND THEIR SYMBOLISM AS USED ON ITAJIME-DYED JUBAN by SUSAN ELIZABETH GUNTER (Under the Direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst) ABSTRACT Itajime is a little-known process of resist-dyeing that employs sets of wooden boards carved in mirror image of one another to clamp together a piece of folded fabric. Itajime was used extensively to decorate Japanese women’s underkimono (juban). The objectives of this research were to examine a sample of sixty-five itajime-dyed garments, to identify the motifs used to decorate the garments, to ascertain the symbolic meanings of the motifs, and to create a catalog of the sixty-five itajime-dyed garments. The motifs appearing on the itajime-dyed garments were most often botanical, although other motifs in the following categories were also present: animal/bird/insect motifs, water-related motifs, everyday object motifs, and geometric designs and abstract shapes. INDEX WORDS: Itajime, Japanese Motifs, Resist Dyeing, Underkimono, Juban JAPANESE DESIGN MOTIFS AND THEIR SYMBOLISM AS USED ON ITAJIME-DYED JUBAN by SUSAN ELIZABETH GUNTER A.B., The University of Georgia, 1999 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2003 © 2003 Susan Elizabeth Gunter All Rights Reserved. JAPANESE DESIGN MOTIFS AND THEIR SYMBOLISM AS USED ON ITAJIME-DYED JUBAN by SUSAN ELIZABETH GUNTER Major Professor: Patricia Hunt-Hurst Committee: Glen Kaufman J. Nolan Etters Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2003 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, Glen Kaufman, and Nolan Etters, for the support, kindness, and patience they have shown in all aspects of my graduate studies during the past two years. -

Daftar Pustaka

Daftar Pustaka Sumber Buku Adetiani, Asri. 2007. Analisis Pengaruh Budaya Barat terhadap Kimono pada Era Taisho (1912-1926). Skripsi. Jakarta: Universitas Bina Nusantara. Fitri, Riezkia. A. 2007. Makna Kimono dan Kaitannya dengan Pemakaian Kimono oleh Wanita Jepang. Skripsi. Jakarta : Universitas Darma Persada. Frederic, Louis. 2002. Japan Encyclopedia. London: Belknap Press Of Hardvard University Press. Koentjaraningrat. 1986. Pengantar Ilmu Antropologi. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta. Maryati, Kun dan Suryati, Juju. 2001. Sosiologi. Jakarta: Esis. Sandhoro, Kundharu, dkk. 2012. Batik-Kimono: Pengembangan Desain dan Motif dalam Mendukung Industri Kreatif di Indonesia dan Jepang, Surakarta: Universitas Sebelas Maret Stevens, Rebecca A.T dan Wada, Yoshiko Iwamoto 1996. The Kimono Inspiration Art and Art to Wear. Woshington, D.C: The Textile Museum. Surajaya, I. Ketut. 1993. Pengantar Sejarah Jepang. Depok: Fakultas Sastra Universitas Indonesia. Takeo, Kuwabara. 1983. Japan and Western Civilization. Tokyo: Universitas of Tokyo Press. Yamanaka, Norio. 1982. The Book of Kimono. Tokyo: Kodansha Intern. Sumber Internet Alexander, L. (2017, April 4). The Social Life of Kimono Innovation Faces Tradition in The Fight to Keep Kimono Relevant. Diambil kembali dari http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/207/04/15/books-reviews/social-life- kimono-innovation-faces-tradition-fight-keep-kimono-relevant/ Amidyanie. (2016, Mei 22). Kamus Aksesoris Kimono. Diambil kembali dari http://amidyanie.wordpress.com/tag/kimono Batik dan Kimono. (2011, Juni 19). Diambil kembali dari Fashion Pro Magazine: http://www.fashionpromagazine.com/2011/06/batik-k mono-3/i Chew, E. (2016, Agustus 12). A Japanese Furisode Kimono can also be Worn as an Amazing Wedding Dress. Diambil kembali dari https://www.yomyomf.com/a- japanese-can-also-be-worn-as-an-amazing-wedding-dress/ Croft, E. -

Japanese Kosode Fragments of the Edo Period (1615-1868): a Recent Acquisition by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 Japanese Kosode Fragments of the Edo Period (1615-1868): A Recent Acquisition by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Joyce Denney Metropolitan Museum of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Denney, Joyce, "Japanese Kosode Fragments of the Edo Period (1615-1868): A Recent Acquisition by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 510. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/510 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Japanese Kosode Fragments of the Edo Period (1615-1868): A Recent Acquisition by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York by Joyce Denney The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, recently acquired a remarkable group of over thirty-five Japanese textiles, the majority of which are probably pieces from kosode robes of the Edo period (1615-1868). This paper will serve as a brief introduction to the collection, which will be on view next summer in the Museum's Japanese galleries. This introduction to the recent acquisition consists of three parts. The first part discusses a few of the pieces from the recently acquired group that have companions in the Nomura collection of the National Museum of Japanese History (Kokuritsu Rekishi Minzoku Hakubutsukan) in Sakura, Chiba, Japan. -

The Kimono & the Haori

Red and pink silk kimono, ca. 1930s. Ryerson FRC2013.03.007. Gift of R. Vanderpeer. Photograph by Victoria Hopgood, 2018. THE KIMONO & THE HAORI By Jennifer Dares & The word kimono means “thing to wear” in Japanese; the original word is Cecilia Martins Gomes kirumono (Steele 2005; Milhaupt 2014). This paper seeks to analyze what MA Fashion Students aspects of kimono are sustainable. To answer that question two styles of kimono from the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection were examined using November 9, 2018 the methodology developed by Mida and Kim in The Dress Detective (2015). We will show that the elegant design of the kimono uses zero waste in its creation, allows for alteration and facilitates reuse, and the loose fit reinforces sustainable qualities of longevity. Kimono are T-shaped robes with long wide sleeves cut in straight lines, and the haori is a variation thereof. Traditionally cut from a single width of fabric, there is virtually no waste in the creation of the garment. Although the wearing of traditional kimono has been in decline, kimono are still worn, but usually for milestone events such as weddings and graduations. Designs have evolved over time to incorporate modern ready to wear features such as zippers and Velcro or the use of washable polyester. 1 Red and pink silk kimono, A red and pink floral silk kimono: This red and pink floral silk kimono ca. 1930s. Ryerson (FRC2013.03.007) has long sleeves that signal that this garment was intended FRC2013.03.007. Gift of R. to be worn by a young woman. -

Official Gazette

OFFICIAL GAZETTE EXTRA Prir≫£> FrHtinn GOVERNMENT PRINTING BUREAU No. 6 TUESDAY, JANUARY 20, 1948 NOTIFICATIONS Price Board Notification No. 38 January 20, 1948 Of the Price Board Notification No. 927 of October, 1947 (concerning the designation of the controlled selling prices of clogs, etc.), the each paragraphs of paulownia-wood bastard grain for men, paulownia-wood bastard grain for women, lacquered miscellaneous wood for women, paulownia-wood (lacquered) for children, 6.5 sun & 6 sun, and paulownia-wood (lacquered) for children, 5.5 sun & 5 sun in the column of clogs of I and those in the column of clog-thong of III shall be revised respectively as follows, and of the appendix in the column of clogs of I, the paragraph " the prices for clogs made of latifoliate wood may be added by 30 per cent" shall be deleted: Director-General of Price Board WADA Hiroo Controlled selling Controlled selling price of producer price of dealer (Unit: one pair) (Unit: one pair) Paulownia-wood bastard grain, for men \44.40 \68.00 Paulownia-wood bastard grain, for women 38.90 59.00 Lacquered miscellaneous wood, for women 31.20 47.50 Lacquered paulownia-wood, for children, 6.5 sun & 6 sun 42.40 64.50 , 5.5 sun & 5 sun 39.70 60.50 III. Cloe-thone Controlled selling Controlled selling Controlled selling price of producer price of wholesaler price of retailer No. Used cloth (Unit: 10 pair) (Unit: 1 pair) (Unit: 1 pair) 1. Chiffon velvet ribbon-cloth, pure-silk clog- \567.00 \62.37 \81.00 thong, velvet No. -

Search Terms 2019.Xlsx

Basic Terms 着物 Kimono 着付け Kitsuke The art and process of dressing in kimono 振袖 Furisode Long-sleeved kimono for young women 訪問着 Houmongi Formal visiting wear kimono 留袖 Tomesode Short-sleeved kimono 黒留袖 Kuro-tomesode Black kimono with designs on hem 色留袖 Iro-tomesode Coloured kimono with designs on hem 色無地 Iromuji Solid-coloured kimono 江戸小紋 Edo-komon Pattern of tiny dots that looks solid 付け下げ Tsukesage Semi-formal kimono 小紋 Komon Casual all-over pattern 浴衣 Yukata Cotton summer kimono 家紋 Kamon Family crest アンサンブル Ensemble 帯 Obi Waist sash 丸帯 Maru obi Formal (semi-obsolete) obi 袋帯 Fukuro obi Full-width formal obi 昼夜帯 Chuuya obi Reversible "day/night" obi 名古屋帯 Nagoya obi Versatile obi with narrow part 半巾帯 Hanhaba obi Narrow casual obi 兵児帯 Heko obi Soft, very casual obi 帯揚げ Obiage Scarf to cover bustle pad in obi 帯締め Obijime Decorative cord to tie obi 三分紐 Sanbu-himo Thin obijime to be worn with obidome 帯留 Obidome Brooch/jewelry for front of obi しごき帯 Shigoki obi Scarf-like accessory for below obi 袴 Hakama Pleated skirt-like garment worn over kimono 襟 Eri Collar 羽織 Haori Short, open jacket 道行 Michiyuki Longer jacket with closing front placket 雨 Ama (rain - use for search with coats, shoes) トンビインバネス Tonbi Coat Victorian-style overcoat 草履 Zori Dressy sandals for wear with kimono 下駄 Geta Wooden sandals for casual wear おこぼ Okobo High platform sandals worn by maiko ポックリ Pokkuri High platform sandals worn by maiko 巾着 Kinchaku Drawstring purse 襦袢 Juban Under-robe 足袋 Tabi Traditional split-toe socks 小物 こもの Komono Small accesories たとう紙 Tatoshi Storage -

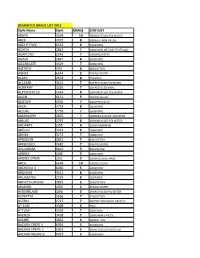

DESIGNTEX GRADE LIST 2013 Style Name Style GRADE CONTENT

DESIGNTEX GRADE LIST 2013 Style Name Style GRADE CONTENT ABAYA 3259 10 100%RECYCLED POLYESTER ABEX 2072 8 100%ZEFTRON NYLON ABOUT FACE 6533 6 100%VINYL ACACIA 2843 7 100%VINYL WITHOUT PHTHALA AGAPETOS 2546 7 100%POLYESTER AGAVE 2847 8 100%VINYL AGGREGATE 3429 7 100%VINYL AGITATO J351 4 28%COTTON AGNES 6544 5 72%POLYESTER ALAYA 2678 8 70%VINYL ALCAZAR 3413 7 20%RECYCLED POLYESTER ALEMANY 3265 7 10%RECYCLED VINYL ALETHOS PLUS 2544 8 100%RECYCLED POLYESTER ALIGN 6151 5 72%POLYESTER ALISTAIR 2992 7 100%POLYESTER ALKAI 2729 8 100%VINYL ALLURE 2756 7 100%VINYL AMARANTH 2855 7 100%BELLA-DURA SOLUTION AMUSE 2767 8 100%RECYCLED POLYESTER ANDANTE J355 4 100%DURAPRENE ANELLO 3224 6 100%VINYL ANNEX 3272 7 100%VINYL APHELION 2831 7 40%COTTON APPLESEED 2682 7 20%POLYESTER AQUARIUM B843 5 40%VISCOSE ARBRES J249 5 100%VINYL ARBRES STRIPE J251 5 100%POLYURETHANE ARCA 6448 10 70%POLYESTER ARCHEVIA II 6066 5 100%VINYL ARGIANO 3411 6 100%VINYL ARLINGTON 2724 8 50%PAPER ARTIST'S CANVAS 2825 5 26%COTTON ARUNDO J330 5 45%POLYESTER ASSEMBLAGE J296 5 29%RECYCLED POLYESTER ASTRATTA 5666 7 57%COTTON ASTRID 2747 7 6%POST INDUSTRIAL RECYCLE AT EASE 3309 6 POLY ATTUSH 3269 7 100%VINYL AVENZA 3408 7 100%LAMB'S WOOL AWARE 2854 6 38%COTTON BACARA CREPE II 6054 5 44%NYLON BACARA STRIPE II 6052 5 18%RECYCLED POLYESTER BACARA WEAVE II 6053 5 100%LINEN Style Name Style GRADE CONTENT BAINBRIDGE 2772 10 100%TREVIRA (R) CS POLYES BANDA 3227 7 100%POLYESTER BANDOL LINEN 6025 8 14%RAYON BANGLES 7352 8 21%ACRYLIC BANYAN 6532 6 21%COTTON BARATTO 3266 9 33%POLYESTER BARNSBURY 2726 8 80%RECYCLED POLYESTER BASKET WEAVER 3296 7 100%OLEFIN BATTISTA 2718 9 7%NYLON BAYOU 5684 7 100%POLYESTER BEAM 2785 8 100%VINYL BEE 4975 6 48%VISCOSE BELENOS 2496 8 39%COTTON BELGRAVE J287 5 12%POLYESTER BELVEDERE 3275 10 49%WOOL BERBER STRIPE 3268 8 60%PETG BIBA H216 10 33%WOOL BIHAR H218 11 32%RECYCLED POLYESTER BLISS 2770 8 34%POST CONSUMER RECYCLED BLOCK PRINT 3447 8 POLY BLOWING FLOWER 8030 7 40%PRECONSUMER RECY. -

HAORI: an ASPECT of CULTURE by Benedikte Goronga I Still Remember the First Time I Heard the Word Haori

Fig. 1. Haori from: the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection, FRC2017.01.002 HAORI: AN ASPECT OF CULTURE By Benedikte Goronga I still remember the first time I heard the word haori. My aunt, who lives in MA Fashion Student Japan, was visiting, and I proudly showed her my beautiful vintage “kimono” that I had recently purchased. She told me that what I thought was a kimono, November 16, 2019 is actually called a haori. The main difference is that while the kimono is a floor-length robe, the haori is a jacket worn on top. Traditionally, the haori was a male garment, and women did not wear it until around 1985 (Dees 103). Although the haori is not the same as a kimono, it is part of traditional Japanese dress, which became their national costume during the first decade of the twentieth century (Dees 11). Therefore, it is an essential part of kimono culture. This paper seeks to analyze and explore the similarities and differences between two Japanese haori jackets; privately owned pink silk haori (see fig.2) and a black and wine red reversible silk haori from the Ryerson Fashion Research Collection, FRC2017.01.002 (see fig.1). 1 Fig. 2. Privately owned Pink Silk Haori from: author’s photo album. 2 Fig. 3. Private pink silk In the book The Social Psychology of Clothing, Susan Kaiser looks at how haori & black and wine culture emerges and how it is maintained. Clothes can play an important role in red reversible silk haori this process; she explains that “Shared usage and understanding of clothes can from: the Ryerson Fashion cultivate a sense of interconnectedness among members of a group” (351).