Vol. 43, No. 3: Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

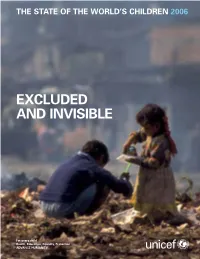

Excluded and Invisible

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 EXCLUDED AND INVISIBLE THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 © The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2005 The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Permission to reproduce any part of this publication The State of the World’s Children 2006 is required. Please contact the Editorial and Publications Section, Division of Communication, UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, UNICEF NY (3 UN Plaza, NY, NY 10017) USA, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: 212-326-7434 or 7286, Fax: 212-303-7985, E-mail: [email protected]. Permission E-mail: [email protected] will be freely granted to educational or non-profit Website: www.unicef.org organizations. Others will be requested to pay a small fee. Cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ94-1393/Shehzad Noorani ISBN-13: 978-92-806-3916-2 ISBN-10: 92-806-3916-1 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the advice and contributions of many inside and outside of UNICEF who provided helpful comments and made other contributions. Significant contributions were received from the following UNICEF field offices: Albania, Armenia, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Republic of Moldova, Serbia and Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Venezuela and Viet Nam. Input was also received from Programme Division, Division of Policy and Planning and Division of Communication at Headquarters, UNICEF regional offices, the Innocenti Research Centre, the UK National Committee and the US Fund for UNICEF. -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (A) – January 2003 I was captured together with my husband, my three young children and other civilians as we were fleeing from the RUF when they entered Jaiweii. Two rebels asked to have sex with me but when I refused, they beat me with the butt of their guns. My legs were bruised and I lost my three front teeth. Then the two rebels raped me in front of my children and other civilians. Many other women were raped in public places. I also heard of a woman from Kalu village near Jaiweii being raped only one week after having given birth. The RUF stayed in Jaiweii village for four months and I was raped by three other wicked rebels throughout this A woman receives psychological and medical treatment in a clinic to assist rape period. victims in Freetown. In January 1999, she was gang-raped by seven revels in her village in northern Sierra Leone. After raping her, the rebels tied her down and placed burning charcoal on her body. (c) 1999 Corinne Dufka/Human Rights -Testimony to Human Rights Watch Watch “WE’LL KILL YOU IF YOU CRY” SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SIERRA LEONE CONFLICT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol. -

Millions of Civilians Have Been Killed in the Flames of War... But

VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 131 • 2003 “Millions of civilians have been killed in the flames of war... But there is hope too… in places like Sierra Leone, Angola and in the Horn of Africa.” —High Commissioner RUUD LUBBERS at a CrossroadsAfrica N°131 - 2003 Editor: Ray Wilkinson French editor: Mounira Skandrani Contributors: Millicent Mutuli, Astrid Van Genderen Stort, Delphine Marie, Peter Kessler, Panos Moumtzis Editorial assistant: UNHCR/M. CAVINATO/DP/BDI•2003 2 EDITORIAL Virginia Zekrya Africa is at another Africa slips deeper into misery as the world Photo department: crossroads. There is Suzy Hopper, plenty of good news as focuses on Iraq. Anne Kellner 12 hundreds of thousands of Design: persons returned to Sierra Vincent Winter Associés Leone, Angola, Burundi 4 AFRICAN IMAGES Production: (pictured) and the Horn of Françoise Jaccoud Africa. But wars continued in A pictorial on the African continent. Photo engraving: Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Aloha Scan - Geneva other areas, making it a very Distribution: mixed picture for the 12 COVER STORY John O’Connor, Frédéric Tissot continent. In an era of short wars and limited casualties, Maps: events in Africa are almost incomprehensible. UNHCR Mapping Unit By Ray Wilkinson Historical documents UNHCR archives Africa at a glance A brief look at the continent. Refugees is published by the Media Relations and Public Information Service of the United Nations High Map Commissioner for Refugees. The 17 opinions expressed by contributors Refugee and internally displaced are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do UNHCR/P. KESSLER/DP/IRQ•2003 populations. not imply the expression of any With the war in Iraq Military opinion or recognition on the part of officially over, UNHCR concerning the legal status UNHCR has turned its Refugee camps are centers for of a territory or of its authorities. -

UNICEF Photo of the Year – Previous Award Winners

UNICEF Photo of the Year – Previous Award Winners 2014 First Prize Insa Hagemann / Stefan Finger, Germany, laif Their reportage on the effects of sextourism in the Philippines gives an insight in the situation of children whose fathers live abroad. Second Prize Christian Werner, Germany, laif For his reportage on internally displaced people from Shinghai district, Iraq Third Prize Brent Stirton, South Africa, Getty Images for his reportage “Before and after eye surgery” on children with congenital cataract blindness in India. 2013 Winner Niclas Hammarström, Sweden, Kontinent His photo reportage captures the life of the children in Aleppo caught between the frontlines. 2012 First Prize Alessio Romenzi, Italien, Agentur Corbis Images The winning picture shows a girl waiting for medical examination at a hospital in Aleppo, Syria. The camera captures the fear in her eyes as she looks at a man holding a Kalashnikov. Second Prize Abhijit Nandi, India, Freelance Photographer In a long-term photo project, the photographer documents the many different forms of child labor in his home country. Third Prize Andrea Gjestvang, Norwegen, Agentur Moment The third prize was awarded to Norwegian photographer Andrea Gjestvang for her work with the victims of the shooting on Utøya Island. Forth Prize Laerke Posselt, Dänemark, Agentur Moment for her look behind the scenes of beauty pageants for toddlers in the USA. 1 2011 First Prize Kai Löffelbein, Germany, Student, University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Hannover for his photo of a boy at the infamous toxic waste dump Agbogbloshie, near Ghana’s capital Accra. Surrounded by highly toxic fumes and electronic waste from Western countries, the boy is lifting the remnants of a monitor above his head. -

Essays on Spatial Development by Alexander David Rothenberg a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements

Essays on Spatial Development by Alexander David Rothenberg A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Bryan S. Graham, Chair Professor Edward Miguel Professor Patrick Kline Professor Robert Helsley Spring 2012 Essays on Spatial Development Copyright 2012 by Alexander David Rothenberg Abstract Essays on Spatial Development by Alexander David Rothenberg Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Bryan S. Graham, Chair This dissertation contains three essays on the relationship between the spatial distribution of economic activity and di↵erent types of public goods. In the first essay, I study how changes in transport infrastructure a↵ect the location decisions of firms by examining how manufacturers responded to changes in road quality in Indonesia. Using new data, I docu- ment massive upgrades to Indonesia’s highway networks during the 1990s, a period in which national transportation funding increased by 83 percent. I first show that these road im- provements were accompanied by a significant dispersion of manufacturing activity, and that di↵erent industries responded in ways predicted by theory. To make better counterfactual predictions, I develop a structural model of location choice in which firms face a trade o↵: locating closer to demand sources requires firms to pay higher factor prices. The model predicts that some location characteristics relevant to firms are determined in equilibrium, necessitating the use of instrumental variables. I estimate a random coefficients logit model with endogenous choice characteristics and find significant di↵erences in firms’ willingness to pay for greater market access across di↵erent industrial sectors. -

Listening to the Heartbeat of Our Ministry Saturday

The Steffescope Volume 7, 2004 © 2004 Saturday, January 10 Dear Friends and Family: Happy New Year to all of you! The start of 2004 finds us safely back in Togo for a month of service. Thanks for your prayers for us. After spending almost eight months here last year, it was very strangely like coming home when we drove in today. We were met by the two non-variables that so characterize Togo at this time of the year: the harmatan and grassfires. As we try to stop coughing and wheezing and struggle to catch our breath, please excuse us and take a moment to see how you do on this quiz designed to see what you remember about Togo (the answers are in the postscript): 1. We’ll start with an easy one. Togo is on the continent of: (A) Africa (B) Australia (C) No such place 2. The Harmatan refers to great swirling clouds of dust reaching high into the atmosphere that ride northerly winds and cover much of Western Africa from December to March each year. This dust comes from which of the following deserts? (A) Mojave (B) Gobe (C) Sahara 3. Togo is approximately the size of which of the following states? (A) Michigan (B) West Virginia (C) California 4. The population of Togo is approximately: (A) 2.5 million (B) 3.8 million (C) 5.3 million 5. Although there are approximately 37 ethnic groups and corresponding languages spoken in Togo, which language is the national language? (A) French (B) English (C) German 6. After WWII, the German colony of Togoland was divided into two countries. -

Global Girlhood Report 2020: How COVID-19 Is Putting Progress in Peril

THE GLOBAL GIRLHOOD REPORT 2020 How COVID-19 is putting progress in peril Save the Children believes every child deserves a future. Around the world, we work every day to give children a healthy start in life, the opportunity to learn and protection from harm. When crisis strikes, and children are most vulnerable, we are always among the first to respond and the last to leave. We ensure children’s unique needs are met and their voices are heard. We deliver lasting results for millions of children, including those hardest to reach. We do whatever it takes for children – every day and in times of crisis – transforming their lives and the future we share. A note on the term ‘girls’ This report uses the term ‘girl’ throughout to include children under 18 years who identify as girls and those who were assigned female sex at birth. The quantitative data in this report is based on sex rather than gender disaggregation, so the terms ‘girl’ and ‘boy’ will usually refer to children’s sex without knowledge of their gender identity due to a lack of gender-disaggregated data and data on intersex children and adults globally. Children of all sexes and genders will identify with some of the experiences described in this report. The focus and terminology used is not intended to exclude or deny those experiences, but to contribute to understandings of gender inequality for all children, through examination of patterns and experiences shared based on sex and gender. Acknowledgements This report was written by Gabrielle Szabo and Jess Edwards, with contributions and recommendations from girl advisers: Fernanda (in consultation with other members of adolescent network, RedPazMx), Krisha, Maya and Abena. -

(2014) Alphonso Lisk-Carew: Early Photography in Sierra Leone. Phd

Crooks, Julie (2014) Alphonso Lisk‐Carew: early photography in Sierra Leone. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18564 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Alphonso Lisk-Carew: Early Photography in Sierra Leone Julie Crooks Thesis Submitted for PhD March 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology SOAS University of London © 2014 Julie Crooks All rights reserved Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

4000 Volunteers Requested In

PEACE CORPS NEWS VOL. 2 NO. 2 A Special College Supplement SPRING, 1963 4,000 Volunteers Requested In '63 Philosophy Liberal Arts Grad Describes Students Will Work In Nepal Fill Many Jobs (Editor's note: Jim Fisher, More than 4,000 new Peace a philosophy graduate of Corps Volunteers will be se- Princeton, is now teaching lected during the next few English as a second language months to serve in 45 developing in Nepal. The following let- nations around the world. Some ter describes his work.) of these men and women will be In the middle of final exami- replacing Volunteers who are nations last Spring I suddenly completing their two-year period found myself forced into decid- of service this year. ing what would happen to me in Others will be filling com- the world lying outside of pletely new assignments request- Princeton, N. J.: I chose what ed by countries in Africa, Latin I later saw advertised as "Land America, the Near and Far East of Yeti and Everest." and South Asia. Some 300 dif- The day following graduation ferent skill areas are represented I began training an average of in the jobs, most of which will 12 hours per day at George be filled by the end of 1963. Washington University in Wash- Opportunities for Americans ington, D. C. About half the to invest their time and talent time was concentrated on lan- in helping people to help them- guage study, the other half in selves are greater now than at world affairs, American studies, any time in the brief history of and Nepal area studies. -

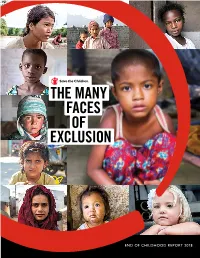

The Many Faces of Exclusion: 2018 End of Childhood Report

THE MANY FACES OF EXCLUSION END OF CHILDHOOD REPORT 2018 Six-year-old Arwa* and her family were displaced from their home by armed conflict in Iraq. CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 End of Childhood Index Results 2017 vs. 2018 7 THREAT #1: Poverty 15 THREAT #2: Armed Conflict 21 THREAT #3: Discrimination Against Girls 27 Recommendations 31 End of Childhood Index Rankings 32 Complete End of Childhood Index 2018 36 Methodology and Research Notes 41 Endnotes 45 Acknowledgements * after a name indicates the name has been changed to protect identity. Published by Save the Children 501 Kings Highway East, Suite 400 Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 United States (800) 728-3843 www.SavetheChildren.org © Save the Children Federation, Inc. ISBN: 1-888393-34-3 Photo:## SAVE CJ ClarkeTHE CHILDREN / Save the Children INTRODUCTION The Many Faces of Exclusion Poverty, conflict and discrimination against girls are putting more than 1.2 billion children – over half of children worldwide – at risk for an early end to their childhood. Many of these at-risk children live in countries facing two or three of these grave threats at the same time. In fact, 153 million children are at extreme risk of missing out on childhood because they live in countries characterized by all three threats.1 In commemoration of International Children’s Day, Save the Children releases its second annual End of Childhood Index, taking a hard look at the events that rob children of their childhoods and prevent them from reaching their full potential. WHO ARE THE 1.2 BILLION Compared to last year, the index finds the overall situation CHILDREN AT RISK? for children appears more favorable in 95 of 175 countries. -

Religion and Peacemaking in Sierra Leone

i RELIGION AND PEACEMAKING IN SIERRA LEONE Joseph Gaima Lukulay Moiba HCPS, Cand. Mag., PPU1&2, MA, Cand.Theol., PTE. Director of Studies: Prof. Bettina Schmidt, PhD, D.Phil. University of Wales: Trinity Saint David, Lampeter Second Supervisor: Dr Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, PhD, LicDD. University of Wales: Trinity Saint David, Lampeter STATEMENT: This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales: Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities and Performing Arts to the University of Wales: Trinity Saint David. SEPTEMBER 2016 ii Declaration This work has not previously been accepted as a whole or in part for any degree and has not been concurrently submitted for any degree. Signed: JGLMOIBAREV (Signed) (Candidate) Date: 8. 9. 2016 Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnote giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed: JGLMOIBAREV (Signed) (Candidate) Date: 8. 9. 2016 Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and abstract to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: JGLMOIBAREV (Signed) (Candidate) Date: 8. 9. 2016 iii Abstract: This thesis concerns religion as a peacemaking tool in Sierra Leone. The vast majority of people in Sierra Leone consider themselves to be Christians, Muslims and / or adherents of African Traditional Religion (ATR). -

Sexed Pistols

United Nations University Press is the publishing arm of the United Nations University. UNU Press publishes scholarly and policy-oriented books and periodicals on the issues facing the United Nations and its peoples and member states, with particular emphasis upon international, regional and transboundary policies. The United Nations University was established as a subsidiary organ of the United Nations by General Assembly resolution 2951 (XXVII) of 11 December 1972. It functions as an international community of scholars engaged in research, postgraduate training and the dissemination of knowledge to address the pressing global problems of human survival, development and welfare that are the concern of the United Nations and its agencies. Its activities are devoted to advancing knowledge for human security and development and are focused on issues of peace and governance and environment and sustainable development. The Univer- sity operates through a worldwide network of research and training centres and programmes, and its planning and coordinating centre in Tokyo. Sexed pistols Sexed pistols: The gendered impacts of small arms and light weapons Edited by Vanessa Farr, Henri Myrttinen and Albrecht Schnabel United Nations a University Press TOKYO u NEW YORK u PARIS 6 United Nations University, 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. United Nations University Press United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8925, Japan Tel: þ81-3-5467-1212 Fax: þ81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] general enquiries: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office at the United Nations, New York 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-2060, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: þ1-212-963-6387 Fax: þ1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University.