Regulatory Challenges and Opportunities in the New ICT Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAP S/4HANA Led Digital Transformation Globe Telecom Inc. Company Information

SAP® Innovation Awards 2020 Entry Pitch Deck SAP S/4HANA led Digital Transformation Globe Telecom Inc. Company Information Headquarters Manila, Philippines Industry Communications services, Remittance Web site https://www.globe.com.ph/ Globe Telecom, Inc., commonly shortened as Globe, is a major provider of telecommunications services in the Philippines. It operates one of the largest mobile, fixed line, and broadband networks in the country. Globe Telecom's mobile subscriber base reached 60.7 million as of end-December 2017 © 2019 SAP SE or an SAP affiliate company. All rights reserved. ǀ PUBLIC 2 SAP S/4HANA led Digital Transformation Globe Telecom Inc. Challenge Globe Telecom has been using SAP for all their business units globally spread across business functions of finance & accounting, procurement, and sales & distribution. Over a period of time, processes became fragmented and inefficient due to manual interventions, causing concerns over unavailability of required business insights, delay in decision making, user’s productivity and their experience. It realized the need of having next-gen ERP enabling best-in class business operations and workplace experience supporting ever changing business needs and future innovations Solution Globe Telecom partnered with TCS for consulting led SAP S/4HANA conversion. With TCS’ advisory services and industry best practices, Globe Telecom has been able to standardize, simplify, integrate, automate and optimize 50+ business processes across the business units. TCS leveraged proprietary transformation delivery methodology, tools and accelerators throughout the engagement ensuring faster time to market minimizing business disruptions. Outcome With SAP S/4HANA, Globe Telecom is able to improve system performance, speed up processing of financial transactions, faster & error free closing of books, cash flow reporting and management reporting. -

Technical Report

Cost-Effective Cloud Edge Traffic Engineering with CASCARA Rachee Singh Sharad Agarwal Matt Calder Victor Bahl Microsoft Abstract Inter-domain bandwidth costs comprise a significant amount of the operating expenditure of cloud providers. Traffic engi- neering systems at the cloud edge must strike a fine balance between minimizing costs and maintaining the latency ex- pected by clients. The nature of this tradeoff is complex due to non-linear pricing schemes prevalent in the market for inter-domain bandwidth. We quantify this tradeoff and un- cover several key insights from the link-utilization between a large cloud provider and Internet service providers. Based Figure 1: Present-day and CASCARA-optimized bandwidth allo- on these insights, we propose CASCARA, a cloud edge traffic cation distributions for one week, across a pair of links between a engineering framework to optimize inter-domain bandwidth large cloud provider and tier-1 North American ISPs. Costs depend allocations with non-linear pricing schemes. CASCARA lever- on the 95th-percentile of the allocation distributions (vertical lines). ages the abundance of latency-equivalent peer links on the CASCARA-optimized allocations reduce total costs by 35% over the cloud edge to minimize costs without impacting latency sig- present-day allocations while satisfying the same demand. nificantly. Extensive evaluation on production traffic demands of a commercial cloud provider shows that CASCARA saves In this work, we show that recent increases in interconnec- 11–50% in bandwidth costs per cloud PoP, while bounding tion and infrastructure scale enable significant potential to re- the increase in client latency by 3 milliseconds1. duce the costs of inter-domain traffic. -

Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation September 30, 2008 Disclaimer This presentation has been prepared by SK Telecom Co., Ltd. (“the Company”). This presentation is being presented solely for your information and is subject to change without notice. No representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made and no reliance should be placed on the accuracy, fairness or completeness of the information presented. The Company, its affiliates, advisers or representatives accept no liability whatsoever for any losses arising from any information contained in the presentation. This presentation does not constitute an offer or invitation to purchase or subscribe for any shares of the Company, and no part of this presentation shall form the basis of or be relied upon in connection with any contract or commitment. The contents of this presentation may not be reproduced, redistributed or passed on, directly or indirectly, to any other person or published, in whole or in part, for any purpose. 1 TableTable ofof ContentsContents 1 Industry Overview 2 Financial Results 3 Growth Strategy 4 Investment Assets & Commitments to Shareholders 2 1 Industry Overview 2 Financial Results 3 Growth Strategy 4 Investment Assets & Commitments to Shareholders 3 OverviewOverview ofof KoreanKorean WirelessWireless MarketMarket Revenue growth driver is shifting to wireless data sector (000s, %) Subscriber Trend Wireless Market: Total & Data Revenue 93.2% (KRW Bn) 91.3% 92.7% 83.2% 89.8% 79.4% 20,107 75.9% 45,275 70.1% 44,266 44,983 18,825 43,498 40,197 17,884 38,342 16,578 36,586 33,592 16,006 14,581 14,682 5,705 9,056 12,344 166 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008.1Q 2008. -

An Overview of the Communication Decency Act's Section

Legal Sidebari Liability for Content Hosts: An Overview of the Communication Decency Act’s Section 230 Valerie C. Brannon Legislative Attorney June 6, 2019 Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934, enacted as part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 (CDA), broadly protects online service providers like social media companies from being held liable for transmitting or taking down user-generated content. In part because of this broad immunity, social media platforms and other online content hosts have largely operated without outside regulation, resulting in a mostly self-policing industry. However, while the immunity created by Section 230 is significant, it is not absolute. For example, courts have said that if a service provider “passively displays content that is created entirely by third parties,” Section 230 immunity will apply; but if the service provider helps to develop the problematic content, it may be subject to liability. Commentators and regulators have questioned in recent years whether Section 230 goes too far in immunizing service providers. In 2018, Congress created a new exception to Section 230 in the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act of 2017, commonly known as FOSTA. Post-FOSTA, Section 230 immunity will not apply to bar claims alleging violations of certain sex trafficking laws. Some have argued that Congress should further narrow Section 230 immunity—or even repeal it entirely. This Sidebar provides background information on Section 230, reviewing its history, text, and interpretation in the courts. Legislative History Section 230 was enacted in early 1996, in the CDA’s Section 509, titled “Online Family Empowerment.” In part, this provision responded to a 1995 decision issued by a New York state trial court: Stratton- Oakmont, Inc. -

Point of View

TME the way we see it Digital Services: An Opportunity for Telcos to Reinvent Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Key Drivers for Development of Digital Services 5 2.1 Proliferation of Devices and Deployment of Necessary Infrastructure 5 2.2 Evolution of the Technology Ecosystem to Support Digital Services 6 2.3 Changing Consumer Behavior 6 2.4 CSPs’ Quest for New Services and Revenues Streams 6 3 Defining Digital Services in the realm of CSPs 7 3.1 Mobile Money Transactions 7 3.2 OTT Services 10 3.3 Internet of Things/M2M 11 3.4 Big Data and Analytics 13 4 What’s Next for the CSPs’ Digital Services Strategy? 15 4.1 CSP Initiatives 15 4.2 Net Neutrality — How it Should be Redefined in the Coming Years 18 5 Technology Services Eco-System 19 6 Conclusion 20 The information contained in this document is proprietary. ©2014 Capgemini. All rights reserved. Rightshore® is a trademark belonging to Capgemini. TME the way we see it 1 Introduction The advent of mobile telephony and widespread deployment Similarly, rapid advancements of other Digital Services of the internet have been the greatest recent developments such as widespread deployment of interconnected ‘things’ since the dawn of modern communications industry in the other than traditional communication devices have brought mid-twentieth century. The communications industry has about a revolution of sorts. Also known as the Internet of already gone through major transformations over the last Things (IoT), this is a remarkable development in the field of few decades and will continue to do so for the foreseeable communications that has potential to transform many other future, including in the nature and the content of the services industries. -

Globe Telecom, Inc. Singtel Regional Mobile Investor Day 2011 2 December 2011 Presentation Outline

Globe Telecom, Inc. SingTel Regional Mobile Investor Day 2011 2 December 2011 Presentation Outline 9 Globe Telecom, Inc. (GLO) 9 Macro-Economic & Telco Industry Overview 9 Highlights of 9M 2011 Performance 9 Network and IT Transformation: Program and Investment Highlights 9 9M 2011 Financial Results 2 2 Mobile Industry Backdrop: Industry revenues have recovered from declines of 2010. Globe with sustained revenue market share improvements. Subscriber & Industry Revenues Revenue Market Share • SIMs at 93Mn with penetration at 96.5%; multi- 57.8% 58.9% 58.3% 58.9% 57.7% 56.5% SIM usage still high, and is estimated at 16% 55.5% 55.1% 52.9% • Industry revenues have bottomed out and are up 36.6% 2.2% YoY 35.0% 33.9% 33.7% 32.8% 33.3% 34.3% 34.8% 34.8% • Revenue growth driven by domestic voice and mobile browsing, which offset impact of weak 7.2% 7.2% 8.0% 8.3% 9.0% 9.2% 9.7% 10.1% 10.5% international voice traffic and negative currency effect 3Q09 4Q09 1Q10 2Q10 3Q10 4Q10 1Q11 2Q11 3Q11 Smart/PLDT Globe Digitel Competition Subscriber Market Share • Last October 26, 2011 NTC approved PLDT- 51.4% Digitel deal subject to (1) PLDT divesting 10MHz 17.2% of 3G spectrum held by CURE, and (2) Digitel to Smart/PLDT continue providing nationwide unlimited Globe services Digitel th • Entry of 4 player (San Miguel Corp) still looms, 31.4% but timing remains uncertain 5 Broadband: Continued industry growth, enabled by more affordable devices and operators’ sustained coverage expansion using wireless access technologies Subscriber & Industry Revenues Revenue Market Share* • 4.3 Mn subscribers as of 9M 2011, up 25% from 78.9% 76.5% 75.6% 72.6% same period LY -- About 72% of subs on wireless 71.0% 69.4% 68.5% 68.2% 68.3% access technology (3G HSDPA/HSPA, WiMax) • 9M 2011 industry revenues* at Php17.5 Bn , up 15% 29.0% 30.6% 31.5% 31.8% 31.7% 24.4% 27.4% • Room for further expansion – Internet users 21.1% 23.5% estimated at ~33Mn, comprising <35% of population. -

Hcd-Gnv99d/ Gnv111d

HCD-GNV99D/ GNV111D SERVICE MANUAL E Model HCD-GNV99D/GNV111D Australian Model HCD-GNV111D Ver.1.1 2005.05 • HCD-GNV99D/GNV111D are the Amplifier, DVD player, tape deck and tuner section in MHC-GNV99D/GNV111D. Photo : HCD-GNV111D Model Name Using Similar Mechanism NEW DVD DVD Mechanism Type CDM74H-DVBU101 Section Optical Pick-up Name KHM-310CAB/C2NP TAPE Model Name Using Similar Mechanism NEW Section Tape Transport Mechanism Type CMAT2E2 SPECIFICATIONS Amplifier section Inputs VIDEO INPUT: VIDEO: 1 Vp-p, 75 ohms HCD-GNV111D (phono jacks) AUDIO L/R: Voltage The following are measured at AC 120, 127, 220, 240V 50/60 Hz 250 mV, impedance 47 kilohms DIN power output (rated) TV/SAT AUDIO IN L/R: voltage 250 mV/450 mV, Front speaker: 110 W + 110 W (phono jacks) impedance 47 kilohms (6 ohms at 1 kHz, DIN) MIC 1/2: sensitivity 1 mV, Center speaker: 50 W (phone jack) impedance 10 kilohms (16 ohms at 1 kHz, DIN) Surround speaker: 110 W + 110 W Outputs (6 ohms at 1 kHz, DIN) AUDIO OUT: Voltage 250 mV Continuous RMS power output (reference) (phono jacks) impedance 1 kilohm Front speaker: 160 W + 160 W VIDEO OUT: max. output level 1 Vp-p, (6 ohms at 1 kHz, 10% THD) (phono jack) unbalanced, Sync. Center speaker: 80 W negative load impedance 75 ohms (16 ohms at 1 kHz, 10% THD) COMPONENT VIDEO Surround speaker: 160 W + 160 W OUT: Y: 1 Vp-p, 75 ohms (6 ohms at 1 kHz, 10% THD) PB/CB: 0.7 Vp-p, 75 ohms PR/CR: 0.7 Vp-p, 75 ohms HCD-GNV99D S VIDEO OUT: Y: 1 Vp-p, unbalanced, The following are measured at AC 120, 127, 220, 240V 50/60 Hz (4-pin/mini-DIN jack) Sync. -

Player, Pirate Or Conducer? a Consideration of the Rights of Online Gamers

ARTICLE PLAYER,PIRATE OR CONDUCER? A CONSIDERATION OF THE RIGHTS OF ONLINE GAMERS MIA GARLICK I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................. 423 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................. 426 A. KEY FEATURES OF ONLINE GAMES ............................ 427 B. AGAMER’S RIGHT OF OUT-OF-GAME TRADING?......... 428 C. AGAMER’S RIGHT OF IN-GAME TECHNICAL ADVANCEMENT?......................................................... 431 D. A GAMER’S RIGHTS OF CREATIVE GAME-RELATED EXPRESSION? ............................................................ 434 III. AN INITIAL REVIEW OF LIKELY LEGAL RIGHTS IN ONLINE GAMES............................................................................ 435 A. WHO OWNS THE GAME? .............................................. 436 B. DO GAMERS HAVE RIGHTS TO IN-GAME ELEMENTS? .... 442 C. DO GAMERS CREATE DERIVATIVE WORKS?................ 444 1. SALE OF IN-GAME ITEMS - TOO COMMERCIAL? ...... 449 2. USE OF ‘CHEATS’MAY NOT INFRINGE. .................. 450 3. CREATIVE FAN EXPRESSION –ASPECTRUM OF INFRINGEMENT LIKELIHOOD?.............................. 452 IV. THE CHALLENGES GAMER RIGHTS POSE. ....................... 454 A. THE PROBLEM OF THE ORIGINAL AUTHOR. ................ 455 B. THE DERIVATIVE WORKS PARADOX............................ 458 C. THE PROBLEM OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICATION OF COPYRIGHTED MATERIALS. ....................................... 461 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................. 462 © 2005 YALE -

Reevaluating Internet Service Providers' Liability for Third Party Content and Copyright Infringement Lucy H

Roger Williams University Law Review Volume 7 Issue 1 Symposium: Information and Electronic Article 6 Commerce Law: Comparative Perspectives Fall 2001 Making Waves in Statutory Safe Harbors: Reevaluating Internet Service Providers' Liability for Third Party Content and Copyright Infringement Lucy H. Holmes Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR Recommended Citation Holmes, Lucy H. (2001) "Making Waves in Statutory Safe Harbors: Reevaluating Internet Service Providers' Liability for Third Party Content and Copyright Infringement," Roger Williams University Law Review: Vol. 7: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol7/iss1/6 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roger Williams University Law Review by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes and Comments Making Waves In Statutory Safe Harbors: Reevaluating Internet Service Providers' Liability for Third-Party Content and Copyright Infringement With the growth of the Internet" as a medium of communica- tion, the appropriate standard of liability for access providers has emerged as an international legal debate. 2 Internet Service Prov- iders (ISPs) 3 have faced, and continue to face, potential liability for the acts of individuals using their services to access, post, or download information.4 Two areas of law where this potential lia- bility has been discussed extensively are defamation and copyright 5 law. In the United States, ISP liability for the content of third- party postings has been dramatically limited by the Communica- tions Decency Act of 1996 (CDA). -

Philippines in View Philippines Tv Industry-In-View

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW PHILIPPINES TV INDUSTRY-IN-VIEW Table of Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. MARKET OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. PAY-TV MARKET ESTIMATES ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. PAY-TV OPERATORS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. PAY-TV AVERAGE REVENUE PER USER (ARPU) ...................................................................................................... 7 1.5. PAY-TV CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING ................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. ADOPTION OF DTT, OTT AND VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS ............................................................................... 7 1.7. PIRACY AND UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION ........................................................................................................... 8 1.8. REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................. -

Lake Service Provider Training Manual for Preventing the Spread of Aquatic Invasive Species Version 3.3

Lake Service Provider Training Manual for Preventing the Spread of Aquatic Invasive Species Version 3.3 Lake Service Provider Training Manual developed by: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4025 1-888-646-6367 www.mndnr.gov Contributing authors: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Darrin Hoverson, Nathan Olson, Jay Rendall, April Rust, Dan Swanson Minnesota Waters Carrie Maurer-Ackerman All photographs and illustrations in this manual are owned by the Minnesota DNR unless otherwise credited. Thank you to the many contributors who edited copy and provided comments during the development of this manual, and other training materials. Some portions of this training manual were adapted with permission from a publication originally produced by the Colorado Division of Wildlife and State Parks with input from many other partners in Colorado and other states. Table of Contents Section 1 : Lake Service Provider Basics. 1 What is a Lake “Service Provider”?. 2 What are Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS)?. .2 Why a training and permit?. 3 How do you know if you are a service provider and need a permit?. .3 How to get your service provider permit. .3 Service Provider Vehicle Stickers. 4 Online AIS Training for Your Employees. 4 Follow-up After Training. .5 Contact. .6 Section 2: Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS). .7 Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) . 8 Zebra mussels and Quagga mussels . 9 Spiny waterflea and Fishhook waterflea . 11 Faucet snail . 12 Eurasian watermilfoil . 13 Curly-leaf pondweed. .14 Flowering rush . .15 Invasive Fish Diseases. 16 Other Aquatic Invasive Species . 16 Section 3: Minnesota Aquatic Invasive Species Laws . -

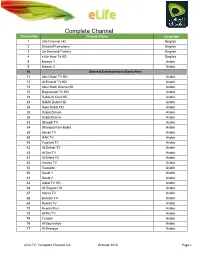

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad