Manomyth: Why Super Political Challenges Produce Supermen and Exclude Superwomen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bomb Queen Volume 3: the Good, the Bad and the Lovely Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BOMB QUEEN VOLUME 3: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE LOVELY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jimmie Robinson | 126 pages | 05 Feb 2008 | Image Comics | 9781582408194 | English | Fullerton, United States Bomb Queen Volume 3: The Good, The Bad And The Lovely PDF Book Bomb Queen, in disguise, travels to Las Vegas in search of a weapon prototype at a gun convention and runs into Blacklight , also visiting Las Vegas for a comic convention. Related: bomb queen 1 bomb queen 1 cgc. More filters Krash Bastards 1. Superpatriot: War on Terror 3. Disable this feature for this session. The animal has mysterious origins; he appears to have some connections to the Mayans of South America. The Bomb Qu Sam Noir: Samurai Detective 3. Share on Facebook Share. Ashe is revealed to be a demon, and New Port City his sphere of influence. These are denoted by Roman numerals and subtitles instead of the more traditional sequential order. I had the worse service ever there upon my last visit. The restriction of the city limits kept Bomb Queen confined in her city of crime, but also present extreme danger if she were to ever leave - where the law is ready and waiting. This wiki. When the hero's efforts prove fruitless, the politician unleashes a chemically-created monster who threatens not only Bomb Queen but the city itself. The animal has mysterious origins and is connected to the Maya of Central America. Sometimes the best medicine is bitter and hard to swallow, and considering the current state of things, it seemed the perfect time for her to return to add to the chaos! Dragon flashback only. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

Drawn&Quarterly

DRAWN & QUARTERLY spring 2012 catalogue EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM EXCERPT FROM GUY DELISLE’S JERUSALEM CANADIAN AUTHOR GUY DELISLE JERUSALEM Chronicles from the Holy City Acclaimed graphic memoirist Guy Delisle returns with his strongest work yet, a thoughtful and moving travelogue about life in Israel. Delisle and his family spent a year in East Jerusalem as part of his wife’s work with the non-governmental organiza- tion Doctors Without Borders. They were there for the short but brutal Gaza War, a three-week-long military strike that resulted in more than 1000 Palestinian deaths. In his interactions with the emergency medical team sent in by Doctors Without Borders, Delisle eloquently plumbs the depths of the conflict. Some of the most moving moments in Jerusalem are the in- teractions between Delisle and Palestinian art students as they explain the motivations for their work. Interspersed with these simply told, affecting stories of suffering, Delisle deftly and often drolly recounts the quotidian: crossing checkpoints, going ko- sher for Passover, and befriending other stay-at-home dads with NGO-employed wives. Jerusalem evinces Delisle’s renewed fascination with architec- ture and landscape as political and apolitical, with studies of highways, villages, and olive groves recurring alongside depictions of the newly erected West Bank Barrier and illegal Israeli settlements. His drawn line is both sensitive and fair, assuming nothing and drawing everything. Jerusalem showcases once more Delisle’s mastery of the travelogue. “[Delisle’s books are] some of the most effective and fully realized travel writing out there.” – NPR ALSO AVAILABLE: SHENZHEN 978-1-77046-079-9 • $14.95 USD/CDN BURMA CHRONICLES 978-1770460256 • $16.95 USD/CDN PYONGYANG 978-1897299210 • $14.95 USD/CDN GUY DELISLE spent a decade working in animation in Europe and Asia. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Reagan's Victory

Reagan’s ictory How HeV Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison Foreword by William J. Bennett Reagan’s Victory: How He Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison 1 FOREWORD By William J. Bennett Ronald Reagan always called me on my birthday. Even after he had left the White House, he continued to call me on my birthday. He called all his Cabinet members and close asso- ciates on their birthdays. I’ve never known another man in public life who did that. I could tell that Alzheimer’s had laid its firm grip on his mind when those calls stopped coming. The President would have agreed with the sign borne by hundreds of pro-life marchers each January 22nd: “Doesn’t Everyone Deserve a Birth Day?” Reagan’s pro-life convic- tions were an integral part of who he was. All of us who served him knew that. Many of my colleagues in the Reagan administration were pro-choice. Reagan never treat- ed any of his team with less than full respect and full loyalty for that. But as for the Reagan administration, it was a pro-life administration. I was the second choice of Reagan’s to head the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It was my first appointment in a Republican administration. I was a Democrat. Reagan had chosen me after a well-known Southern historian and literary critic hurt his candidacy by criticizing Abraham Lincoln. My appointment became controversial within the Reagan ranks because the Gipper was highly popular in the South, where residual animosities toward Lincoln could still be found. -

Copy of Graphic Novel Title List MASTER.Xlsx

Graphic Novels Title Author Artist Call No. Year 300 Miller, Frank Miller, Frank OVERSIZE PN6727.M55 T57 1999 1999 9/11 report: a graphic adaptation Jacobson, Colon HV6432. 7. J33 2006 2006 A Mad look at old movies DeBartolo, Dick PN6727.D422 M68 1973 1973 Abandon the old in Tokyo Tatsumi, Yoshihiro PN6790. J34 T27713 2006 2006 Absolute sandman. Volume one Gaiman, Neil Keith, Sam [et al.] PR6057. A319 A27 v.1 2006 2006 Absolutely no U.S. personnel permitted beyond this point DS557.A61 L4 1972 1972 Achewood Onstad, Chris Onstad, Chris PN6728. A25 O57 2004 2004 Acme Novelty Library Ware, Chris Ware, Chris OVERSIZE. PN6727. W285 A6 2005 2005 Adventures of Super Diaper Baby: the first graphic novel Beard, George Hutchins, Harold CURRLIB. 813 P639as 2002 Alex Kalesniko, Mark Kalesniko, Mark PN6727. K2437 A43 2006 2006 Alias the cat! Deitch, Kim Dietch, Kim PN6727. D383 A45 2007 2007 Alice in Sunderland Talbot, Bryan Talbot, Bryan PN6727. T3426 A44 2007 2007 Aliens Omnibus Vol. 4 Various Various PN6728.A463 O46 v. 4 2008 2008 All‐new, all‐different X‐men Pop‐up Ed. By Repchuck, Caroline PN6728.X536 A55 2007 2007 All‐star Superman Morrison, Grant Quitely, Frank PN6728. S9 M677 2007 American Presidency in political cartoons 1776‐1976 Various E176.1 .A655 1976b 1976 Anime encyclopedia: a guide to Japanesee animation since 1917 Clements, Jonathan REF. NC1766. J3 C53 2006 2006 Arkham Asylum: A Serious Place on a Serious Earth Morrison, Grant McKean, Dave PN6728.B36 A74 2004 2004 Arrival Tan, Shaun CURRLIB. 823 T161ar 2007 2007 Assassin's road Koike, Kazuo Miller, Frank PN6790. -

Resistant Vulnerability in the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-15-2019 1:00 PM Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America Kristen Allison The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Susan Knabe The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kristen Allison 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Allison, Kristen, "Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6086. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6086 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Established in 2008 with the release of Iron Man, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a ubiquitous transmedia sensation. Its uniquely interwoven narrative provides auspicious grounds for scholarly consideration. The franchise conscientiously presents larger-than-life superheroes as complex and incredibly emotional individuals who form profound interpersonal relationships with one another. This thesis explores Sarah Hagelin’s concept of resistant vulnerability, which she defines as a “shared human experience,” as it manifests in the substantial relationships that Steve Rogers (Captain America) cultivates throughout the Captain America narrative (11). This project focuses on Steve’s relationships with the following characters: Agent Peggy Carter, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), and Bucky Barnes (The Winter Soldier). -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Covert Action and Clandestine Activities of the Intelligence Community: Framework for Congressional Oversight in Brief

Covert Action and Clandestine Activities of the Intelligence Community: Framework for Congressional Oversight In Brief Updated August 9, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45196 SUMMARY R45196 Covert Action and Clandestine Activities of the August 9, 2019 Intelligence Community: Framework for Michael E. DeVine Congressional Oversight In Brief Analyst in Intelligence and National Security Since the mid-1970s, Congress’s oversight of the Intelligence Community (IC) has been a fundamental component of ensuring that the IC’s seventeen diverse elements are held accountable for the effectiveness of their programs supporting United States national security. This has been especially true for covert action and clandestine intelligence activities because of their significant risk of compromise and potential long-term impact on U.S. foreign relations. Yet, by their very nature, these and other intelligence programs and activities are classified and shielded from the public. Congressional oversight of intelligence, therefore, is unlike its oversight of more transparent government activities with a broad public following. In the case of the Intelligence Community, congressional oversight is one of the few means by which the public can have confidence that intelligence activities are being conducted effectively, legally, and in line with American values. Covert action is defined in statute (50 U.S.C. §3093(e)) as “an activity or activities of the United States Government to influence political, economic, or military conditions abroad, where it is intended that the role of the United States Government will not be apparent or acknowledged publicly.” When informed of covert actions through Presidential findings prior to their execution—as is most often the case—Congress has a number of options: to provide additional unbiased perspective on how these activities can best support U.S. -

July 8, 2017 • a Public Auction #050 FINE BOOKS & M ANUSCRIPTS and OTHER WORKS on PAPER

Potter & Potter Auctions - July 8, 2017 • A Public Auction #050 FINE BOOKS & M ANUSCRIPTS AND OTHER WORKS ON PAPER INCLUDING WALTER GIBSON’S OWN FILE OF THE SHADOW PULPS AUCTION CONTENTS Saturday, July 8 • 10:00am CST Science & Natural History ...................................2 PREVIEW Continental & British Books & Manuscripts ......18 July 5 - 7 • 10:00am - 5:00pm Militaria ...........................................................29 or by appointment Printed & Manuscript Americana .....................36 INQUIRIES Cartography, Travel & Sporting Books ..............53 [email protected] Comic & Illustration Art ....................................68 phone: 773-472-1442 Literature .........................................................83 Art & Posters ..................................................113 Entertainment ................................................136 Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3759 N. Ravenswood Ave. Suite 121 Chicago, IL 60613 B • fine books & manuscripts & other works on paper SCIENCE & NATURAL HISTORY Lots 1-61 SCIENCE & NATURAL HISTORY 1 3 2 1. Agrippa, Henry Cornelius. The Vanity of Arts and Sciences. 3. Bacon, Roger (trans. Barnaud and Girard). The Mirror of London: Printed by J.C. for Samuel Speed, 1676. SECOND EDITION. Alchemy. Lyon: M. Bonhomme, 1557. Title vignettes, initials, Full calf. Gilt-lettered spine. 8vo. Light edgewear to boards, ornaments. p. [1] 2—134 [misprinting 61 as “16” and 122—23 manuscript ex-libris to f.f.e.p. (“Joseph Page”). as 123—24]. A1—I4. Separate title pages for the other parts: 400/600 Hermes Trismegistus [35—38], Hortulanus [39—56], Calid [57— 108], and Jean de Meun [109—134]. Contemporary mottled calf. 2. Alliette [Etteilla]. Fragment sur les hautes sciences. Small 8vo. Minor marginal damp-stain to one leaf (C1), surface Amsterdam, 1785. FIRST EDITION. Engraved frontispiece of a abrasions to title device from label removal. Scarce. talisman. -

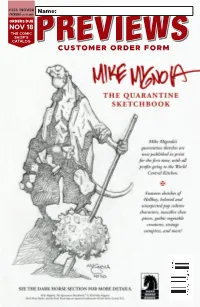

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

Ebook Download Ultimates Ii Ultimate Collection

ULTIMATES II ULTIMATE COLLECTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bryan Hitch | 464 pages | 25 Aug 2010 | Marvel Comics | 9780785149163 | English | New York, United States Ultimates Ii Ultimate Collection PDF Book The X-Men and Magneto. In the wake of the Crossing, Earth's mightiest heroes are in disarray: Thor is powerless, and Iron Man has been replaced - by himself?! For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Miles Morales is still getting used to being Spider-Man when Captain America makes him a very special offer. When the X-Men do the worst thing they could to humanity, the government orders Captain America, Iron Man, Thor and the rest of the Ultimates to bring them down. And then there were six! When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a qualifying affiliate commission. III - 3. Meanwhile, in deep space, Galactus the Lifebringer makes a fateful decision! Loki, the Avengers' fiirst and greatest enemy, has teamed with Dormammu, Old allies make a distress call to the Avengers with news of a terrible enemy that could wipe out humanity itself. What a time for Reptil to make his mark on the Marvel Universe! Ultimate Enchantments does count anvil uses for enchant cost calculation. Who's gone nuts since we last saw them? Following the tragedies of their world tour, the X-Men seek the calming protection of Xavier's school - but their suspicions of his methods only increase. Search results matches ANY words And to solve that, the Ultimates can't just think within the box. Superhero Team see all. Available Stock Add to want list Add to cart Fine.