Mansfield Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

House of Lords Business & Minutes of Proceedings

HOUSE OF LORDS BUSINESS & MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS Session Commencing 17 December 2019 HOUSE OF LORDS BUSINESS No. 1 & MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS Contents Minutes of Proceedings of Tuesday 17 December 2019 1 Minutes of Proceedings of Tuesday 17 December 2019 Parliament Met at 2.30pm pursuant to a proclamation dated 6 November 2019. The Lords Commissioners being seated, the Lord Privy Seal (Baroness Evans of Bowes Park) in the middle with the Lord Speaker (Lord Fowler) and Lord Judge to her right hand and Lord Newby and Baroness Smith of Basildon on her left, the Commission for opening Parliament dated 17 December 2019 was read. The Commons, being present at the Bar, were directed to proceed to the choice of a Speaker and to present the person chosen for the Royal Approbation. Prayers were read by the Lord Bishop of Gloucester. 1 The Lord Speaker The Lord Speaker (Lord Fowler), singly, in the first place, at the Table, took and subscribed the oath and signed an undertaking to abide by the Code of Conduct. 2 Oaths and affirmations The following Lords took and subscribed the oath, or made and subscribed the solemn affirmation, and signed an undertaking to abide by the Code of Conduct: Justin Portal The Lord Archbishop of Canterbury John Tucker Mugabi The Lord Archbishop of York Natalie Jessica Baroness Evans of Bowes Park Angela Evans Baroness Smith of Basildon Richard Mark Lord Newby Igor Lord Judge Thomas Henry Lord Ashton of Hyde Items marked † are new or have been altered John Eric Lord Gardiner of Kimble [I] indicates that the member concerned has Richard Sanderson Lord Keen of Elie a relevant registered interest. -

Constitution and Government 33

CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT 33 GOVERNORS GENERAL OF CANADA. FRENCH. FKENCH. 1534. Jacques Cartier, Captain General. 1663. Chevalier de Saffray de Mesy. 1540. Jean Francois de la Roque, Sieur de 1665. Marquis de Tracy. (6) Roberval. 1665. Chevalier de Courcelles. 1598. Marquis de la Roche. 1672. Comte de Frontenac. 1600. Capitaine de Chauvin (Acting). 1682. Sieur de la Barre. 1603. Commandeur de Chastes. 1685. Marquis de Denonville. 1607. Pierredu Guast de Monts, Lt.-General. 1689. Comte de Frontenac. 1608. Comte de Soissons, 1st Viceroy. 1699. Chevalier de Callieres. 1612. Samuel de Champlain, Lt.-General. 1703. Marquis de Vaudreuil. 1633. ii ii 1st Gov. Gen'l. (a) 1714-16. Comte de Ramesay (Acting). 1635. Marc Antoine de Bras de fer de 1716. Marquis de Vaudreuil. Chateaufort (Administrator). 1725. Baron (1st) de Longueuil (Acting).. 1636. Chevalier de Montmagny. 1726. Marquis de Beauharnois. 1648. Chevalier d'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1747. Comte de la Galissoniere. (c) 1651. Jean de Lauzon. 1749. Marquis de la Jonquiere. 1656. Charles de Lauzon-Charny (Admr.) 1752. Baron (2nd) de Longueuil. 1657. D'Ailleboust de Coulonge. 1752. Marquis Duquesne-de-Menneville. 1658. Vicomte de Voyer d'Argenson. j 1755. Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal. 1661. Baron Dubois d'Avaugour. ! ENGLISH. ENGLISH. 1760. General Jeffrey Amherst, (d) 1 1820. James Monk (Admin'r). 1764. General James Murray. | 1820. Sir Peregrine Maitland (Admin'r). 1766. P. E. Irving (Admin'r Acting). 1820. Earl of Dalhousie. 1766. Guy Carleton (Lt.-Gov. Acting). 1824. Lt.-Gov. Sir F. N. Burton (Admin'r). 1768. Guy Carleton. (e) 1828. Sir James Kempt (Admin'r). 1770. Lt.-Gov. -

BYWATKR CADMAN, His Honour Judge John Heaton

BYWATKR WHO WAS WHO, 1917-1916 Hon. Litt. field. : BYWATER, Ingram, M.A. Oxon. ; Educ. Collegiate, Sheffield ; Lyce"e and Hon. Versailles D., Dublin, Durham, Cambridge ; Imperial, ; Worcester Coll. Oxford; corres. of Ph. D. Athens ; Member Royal B.A., M.A. Called to Bar, Inner Temple, Fellow of Prussian Academy of Sciences ; 1864; joined Midland Circuit, and after- Hon. Fellow of the British Academy ; wards N.E. Circuit on its formation ; Re- b. of Exeter and Queen's Colleges ; London, corder Pontefract, 1877-89 ; J.P. West o. s. of late 27 June 1840 ; John Ingram Riding, Yorks, and on Commission of Peace Charlotte 2nd for of Bywater ; m. 1885, (d, 1908), Boroughs Halifax, Dewsbury, and d. of C. J. Cornish, of Salcombe Regis, Huddersfield. Recreations : shooting, hunt- Devon, and widow of Hans W. Sotheby. ing. Address : Rhyddings House, Ack- Educ. : University College and King's worth, near Pontefract. Club : Junior College Schools, London ; Queen's College, Carlton. [Died 22 Feb. 1906, Oxford. Fellow of Exeter College, 1863 ; CADOGAN, Hon. Frederick William, D L. ; Tutor in the Coll. for several years ; Uni- Barrister ; b. Dec. 16, 1821 ; s. of 3rd Earl Reader in 1883 versity Greek, ; Regius Cadogan and Honoria Louisa Blake, sister of Professor of Greek, and student of Christ 1st Baron Wallscourt ; m. 1851, Lady 1893-1908. Publications : Church, Oxford, Adelaide Paget (d. 1890), d. of 1st Marquess of 1877 the Works Fragments Heraclitus, ; of Anglesey. M.P. Cricklade, 1868-74. of Priscianus for the Berlin Lydus, Academy, Address : 48 Egerton Gardens, S.W. 1886 the text of the Nicomachean Ethics ; [Died 30 Nov. -

Constitution and Government. 21

CONSTITUTION AND GOVERNMENT. 21 GOVERNORS GENERAL OF CANADA—Concluded. ENGLISH. ENGLISH. 1760. Gen. Jeffrey Amherst, (c) 1828. Sir James Kempt. 1764. Gen. James Murray. 1830. Lord Aylmer. 1768. Gen. Sir Guy Carleton. (d) (Lord Dor 1835. Lord Gosford. chester). 1838. Earl of Durham. ' 1778. Gen. Frederick Haldimand. 1839. Poulett Thomson (Lord Sydenham). 1786. Lord Dorchester. 1841. Sir R. Jackson. 1797. Major-General Prescott. 1842. Sir Charles Bagot. 1807. Sir James Craig. 1843. Sir Charles Metcalfe. 1811. Sir George Prevost. 1845. Earl Cathcart. 1815. Sir Gordon Drummond (Acting). 1847. Earl of Elgin. 1816. Sir John Cope Sherbrooke. 1855. Sir Edmund Walker Head. 1818. Duke of Richmond. 1861. Lord Monck. 1819. Sir Peregrine Maitland (Acting). 1820. Earl of Dalhousie. GOVERNORS OF NOVA SCOTIA, (e) AT PORT ROYAL. AT HALIFAX. 1603. Pierre de Monts. 1749. Hon. E. Cornwallis. 1610. Baron de Poutrincourt. 1752. Col. Peregrine Hopson. 1611. Charles de Biencourt. 1753. Col. C. Lawrence. 1623. Charles de la Tour. 1760. J. Belcher (Acting). 1632. Tsaac de Razilly. 1763. Montagu Wilmot. 1641. Chas. d'Aunay Charnisay. 1766. Lord William Campbell. 1651. Chas. de- la Tour. , 1773. F. Legge. 1657. Sir Thomas Temple. (/) 1776. Mariot Arbuthnot. 1670. Hubert de Grandfontaine. 1778. Sir Richard Hughes. 1673. Jacques de Chambly. 1781. Sir A. S. Hamond. 1678. Michel de la Valliere. 1782. John Parr. 1684. Francois M. Perrot. 1791. Richard Bulkeley. 1687. Robineau de Menneval. 1792. Sir John Wentworth. 1690. M. de Villebon. 1808. Sir G. Prevost. 1701. M. de Brouillan. 1811. Sir John Sherbrooke. 1704. Simon de Bonaventure. 1816. Earl of Dalhousie. 1706. M. de Subercase. 1820. -

Inventory Acc.12686 Papers of the Family of Cathcart of Cathcart Lords

Acc.12686 November 2006 Inventory Acc.12686 Papers of the family of Cathcart of Cathcart Lords, Viscounts and Earls Cathcart c.1380 – c.1910 Including the papers of General the Hon. Sir George Cathcart (1794-1854) National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland These papers were deposited by the seventh Earl Cathcart in 2006. Extent: 22 metres Historical Note: These papers of the Cathcart family of Cathcart, Lords, Viscounts and Earls Cathcart and Lords Greenock, cover from the late 14th century to the first decade of the twentieth century. The main figures represented are: • Charles Cathcart, 8th Baron (succeeded 1732, d.1740). Appointed Commander-in- Chief of all British forces in America in 1740, but died on the voyage out. Married Marion Schaw/Shaw, only child of Sir John Schaw and Lady Shaw (nee Margaret Dalrymple) of Greenock. • Charles Schaw Cathcart, 9th Baron (b.1721, succeeded his father 1740, d.1776). Wounded at Fontenoy, and thereafter nicknamed “Patch”. Ambassador to Russia, 1768-1772. Married Jane Hamilton, daughter of Lord and Lady Archibald Hamilton, and sister of Sir William Hamilton. • William Schaw Cathcart, 10th Baron, first Viscount, first Earl Cathcart, first Baron Greenock (b.1755, succeeded his father 1776, d.1843). Commander-in-Chief in Ireland, 1803-1805, Commander-in-Chief in Scotland, 1806-12, Commander-in-Chief of the Expedition to Copenhagen, 1807, Ambassador to Russia, 1812-1820. Married Elizabeth Elliot, cousin to the first Earl of Minto, lady-in-waiting to Queen Charlotte. -

Royalty and the Craft. Count Cagliostro

ROYALTY AND THE CRAFT. time, it had been announced in Grand Lodge, 19th February 1790, that H.R.H. the Duke of Kent had been regularl initiated in the Union Lodge at Geneva, and that THE Installation of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales as y M.W.G.M. is very likely to occupy the attention of H.R.H. the Duke of Sussex had also been initiated at a the public for some time to come. There will, in fact, in the Lodge at Berlin. The Duke of Cumberland, afterwards Masonic world, be hardly any othersubject of general interest King of Hanover, and Gloucester, were also initiated, not only between now and the 28th April, the day fixed for at a later period. H.R.H. the Prince of Wales having sub- the important ceremony, but for some considerable period sequently been chosen G rand Master of Scotland, in 1806, after. It may be as well therefore to place our readers remained Grand Master till 1813 , when, being Regent, he au, courant of the past connection of the Royal Family with resigned the position to his Royal Brother of Sussex, who our Order. It is not, perhaps, generally known, even soon after became Grand Master of the United Grand among Masons, that His Royal Highness is the third Prince Lodge of Masons (1813). In 1813 H.R.H. the Duke of of Wales of the Hanoverian family who has been a member Kent was chosen Grand Master of' the York or Ancient of tho Brotherhood. Twenty years only had elapsed since Masons, and it waa by the united efforts of these two Dukes, the revival of Freemasonry in 1717, when Frederick Prince of Sussex and Kent, that the healing of the great of Wales, son of George II. -

Government Defeat in Lords on European Union (Withdrawal) Bill Tuesday 08/05/2018

Government Defeat in Lords on European Union (Withdrawal) Bill Tuesday 08/05/2018 On 08/05/2018 the government had a defeat in the House of Lords on an amendment to the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill: To delete the provision in the bill that defines exit day as 11pm on 29 March 2019, and to specify instead that exit day may be appointed through regulations. This was defeat number 27 in the parliamentary session. Breakdown of Votes For Govt Against Govt Total No vote Conservative 193 10 203 41 Labour 1 147 148 43 Liberal Democrat 0 86 86 12 Crossbench 28 57 85 101 Bishops 0 2 2 25 Other 11 9 20 22 Total 233 311 544 244 Conservative Votes with the Government Lord Agnew of Oulton Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon Baroness Altmann Baroness Anelay of St Johns Earl Arran Lord Ashton of Hyde Viscount Astor Lord Astor of Hever Earl Attlee Lord Baker of Dorking Lord Bates Baroness Berridge Baroness Bertin Lord Blackwell Lord Blencathra Baroness Bloomfield of Hinton Lord Borwick Baroness Bottomley of Nettlestone Waldrist Lord Bourne of Aberystwyth Lord Brabazon of Tara Viscount Bridgeman Lord Bridges of Headley Lord Brougham and Vaux Baroness Browning Baroness Buscombe Baroness Byford Lord Caine Earl Caithness Lord Callanan Lord Carrington of Fulham Earl Cathcart Lord Cavendish of Furness Lord Chadlington Baroness Chalker of Wallasey Baroness Chisholm of Owlpen Lord Coe Lord Colgrain Lord Colwyn Lord Cope of Berkeley Earl Courtown Baroness Couttie Lord Crathorne Baroness Cumberlege Lord De Mauley Lord Dixon-Smith Lord Dobbs Lord Duncan of Springbank Earl -

Government Defeat in Lords on Fraud (Trials Without a Jury) Bill Tuesday 20/03/2007

Government Defeat in Lords on Fraud (Trials Without a Jury) Bill Tuesday 20/03/2007 On 20/03/2007 the government had a defeat in the House of Lords on an amendment to the Fraud (Trials Without a Jury) Bill: To postpone the second reading of the bill until six months' time. This was defeat number 10 in the parliamentary session. Breakdown of Votes For Govt Against Govt Total No vote Conservative 0 124 124 80 Labour 130 2 132 79 Liberal Democrat 1 58 59 18 Crossbench 12 25 37 164 Bishops 0 2 2 24 Other 0 5 5 8 Total 143 216 359 373 Conservative Votes with the Government Conservative Votes against the Government Baroness Anelay of St Johns Earl Arran Lord Astor of Hever Viscount Astor Earl Attlee Lord Bell Lord Biffen Viscount Bridgeman Lord Brooke of Sutton Mandeville Lord Brougham and Vaux Lord Bruce-Lockhart Baroness Buscombe Baroness Byfo rd Lord Campbell of Alloway Baroness Carnegy of Lour Earl Cathcart Lord Cavendish of Furness Lord Colwyn Lord Cope of Berkeley Earl Courtown Lord Crickhowell Baroness Cumberlege Lord De Mauley Lord Dean of Harptree Lord Denham Lord Dixon-Smith Earl Dundee Viscount Eccles Baroness Eccles of Moulton Lord Eden of Winton Baroness Elles Lord Elton Lord Forsyth of Drumlean Lord Fowler Lord Freeman Baroness Gardner of Parkes Lord Garel-Jones Lord Geddes Lord Glenarthur Lord Glentoran Viscount Goschen Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach Lord Hamilton of Epsom Baroness Hanham Lord Hayhoe Lord Henley Lord Higgins Lord Hodgson of Astley Abbotts Baroness Hooper Lord Howard of Rising Lord Howe of Aberavon Earl Howe Lord -

Hereditary Peers in the House of Lords Since 1999

Library Note Hereditary Peers in the House of Lords Since 1999 The House of Lords Act 1999 ended the centuries-old linkage between the hereditary peerage and membership of the House of Lords. The majority of hereditary Peers left the House of Lords in November 1999, but under a compromise arrangement, 92 of their number, known as ‘excepted’ hereditary Peers still sit in the House today. Since the 1999 Act, there have been numerous proposals put forward for a second stage of major reform of the House of Lords, and for smaller incremental reforms which would end the practice of hereditary by-elections, but to date none of these has succeeded. This Note examines the role of hereditary Peers in the House of Lords since the 1999 Act. It begins by providing a very brief history of the hereditary principle in the House of Lords. It considers the passage of the 1999 Act through Parliament, and the impact it has had on both the composition and the behaviour of the House of Lords. It contains information about the elections and by-elections through which the excepted hereditary Peers have been chosen, as well as details of hereditary Peers who sit by virtue of a life peerage, female hereditary Peers in their own right and a statistical profile of hereditary members of the House today. The Note also outlines proposals for small and large scale reforms put forward by Labour, the current Government and in private members’ bills since 1999. Nicola Newson 26 March 2014 LLN 2014/014 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. -

Roll of the Peerage Created Pursuant to a Royal Warrant Dated 1 June 2004

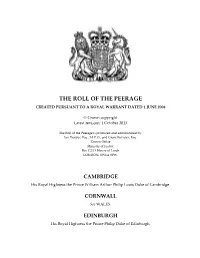

THE ROLL OF THE PEERAGE CREATED PURSUANT TO A ROYAL WARRANT DATED 1 JUNE 2004 © Crown copyright Latest revision: 1 October 2013 The Roll of the Peerage is produced and administered by: Ian Denyer, Esq., M.V.O., and Grant Bavister, Esq. Crown Office Ministry of Justice Rm C2/13 House of Lords LONDON, SW1A 0PW. CAMBRIDGE His Royal Highness the Prince William Arthur Philip Louis Duke of Cambridge. CORNWALL See WALES. EDINBURGH His Royal Highness the Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh. GLOUCESTER His Royal Highness Prince Richard Alexander Walter George Duke of Gloucester. KENT His Royal Highness Prince Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick Duke of Kent. ROTHESAY See WALES. WALES His Royal Highness the Prince Charles Philip Arthur George Prince of Wales (also styled Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay). WESSEX His Royal Highness the Prince Edward Antony Richard Louis Earl of Wessex. YORK His Royal Highness the Prince Andrew Albert Christian Edward Duke of York. * ABERCORN Hereditary Marquess in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: James Marquess of Abercorn (customarily styled by superior title Duke of Abercorn). Surname: Hamilton. ABERDARE Hereditary Baron in the Peerage of the United Kingdom (hereditary peer among the 92 sitting in the House of Lords under the House of Lords Act 1999): Alaster John Lyndhurst Lord Aberdare. Surname: Bruce. ABERDEEN AND TEMAIR Hereditary Marquess in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: Alexander George Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair. Surname: Gordon. ABERGAVENNY Hereditary Marquess in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: Christopher George Charles Marquess of Abergavenny. Surname: Nevill. ABINGER Hereditary Baron in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: James Harry Lord Abinger. -

House of Lords

Session 2019-21 Tuesday No. 43 24 March 2020 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS WRITTEN STATEMENTS AND WRITTEN ANSWERS Written Statements ................................ ................ 1 Written Answers ................................ ..................... 6 [I] indicates that the member concerned has a relevant registered interest. The full register of interests can be found at http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords-interests/ Members who want a printed copy of Written Answers and Written Statements should notify the Printed Paper Office. This printed edition is a reproduction of the original text of Answers and Statements, which can be found on the internet at http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/. Ministers and others who make Statements or answer Questions are referred to only by name, not their ministerial or other title. The current list of ministerial and other responsibilities is as follows. Minister Responsibilities Baroness Evans of Bowes Park Leader of the House of Lords and Lord Privy Seal Earl Howe Deputy Leader of the House of Lords Lord Agnew of Oulton Minister of State, Cabinet Office and Treasury Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Department for International Development Lord Ashton of Hyde Chief Whip Baroness Barran Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Baroness Berridge Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department for Education and Department for International