Declawing Ostrich Chicks (Struthio Camelus) to Minimize Skin Damage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Almond Skins to Improve Nutritional and Functional Properties of Biscuits: an Example of Upcycling

foods Article Use of Almond Skins to Improve Nutritional and Functional Properties of Biscuits: An Example of Upcycling Antonella Pasqualone 1,* , Barbara Laddomada 2 , Fatma Boukid 3 , Davide De Angelis 1 and Carmine Summo 1 1 Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science (DISSPA), University of Bari Aldo Moro, Via Amendola, 165/a, I-70126 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (D.D.A.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Institute of Sciences of Food Production (ISPA), CNR, via Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] 3 Institute of Agriculture and Food Research and Technology (IRTA), Food Safety Programme, Food Industry Area, Finca Camps i Armet s/n, 17121 Monells, Catalonia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23 October 2020; Accepted: 16 November 2020; Published: 20 November 2020 Abstract: Upcycling food industry by-products has become a topic of interest within the framework of the circular economy, to minimize environmental impact and the waste of resources. This research aimed at verifying the effectiveness of using almond skins, a by-product of the confectionery industry, in the preparation of functional biscuits with improved nutritional properties. Almond skins were added at 10 g/100 g (AS10) and 20 g/100 g (AS20) to a wheat flour basis. The protein content was not influenced, whereas lipids and dietary fiber significantly increased (p < 0.05), the latter meeting the requirements for applying “source of fiber” and “high in fiber” claims to AS10 and AS20 biscuits, respectively. The addition of almond skins altered biscuit color, lowering L* and b* and increasing a*, but improved friability. -

Female Desire in the UK Teen Drama Skins

Female desire in the UK teen drama Skins An analysis of the mise-en-scene in ‘Sketch’ Marthe Kruijt S4231007 Bachelor thesis Dr. T.J.V. Vermeulen J.A. Naeff, MA 15-08-16 1 Table of contents Introduction………………………………..………………………………………………………...…...……….3 Chapter 1: Private space..............................................…….………………………………....….......…....7 1.1 Contextualisation of 'Sketch'...........................................................................................7 1.2 Gendered space.....................................................................................................................8 1.3 Voyeurism...............................................................................................................................9 1.4 Properties.............................................................................................................................11 1.5 Conclusions..........................................................................................................................12 Chapter 2: Public space....................……….…………………...……….….……………...…...…....……13 2.1 Desire......................................................................................................................................13 2.2 Confrontation and humiliation.....................................................................................14 2.3 Conclusions...........................................................................................................................16 Chapter 3: The in-between -

I HEDONISM in the QUR'a>N

HEDONISM IN THE QUR’A>N ( STUDY OF THEMATIC INTERPRETATION ) THESIS Submitted to Ushuluddin and Humaniora Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Strata-1 (S.1) of Islamic Theology on Tafsir Hadith Departement Written By: HILYATUZ ZULFA NIM: 114211022 USHULUDDIN AND HUMANIORA FACULTY STATE OF ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY WALISONGO SEMARANG 2015 i DECLARATION I certify that this thesis is definitely my own work. I am completely responsible for content of this thesis. Other writer’s opinions or findings included in the thesis are quoted or cited in accordance with ethical standards. Semarang, July 13, 2015 The Writer, Hilyatuz Zulfa NIM. 114211022 ii iii iv MOTTO QS. Al-Furqan: 67 . And [they are] those who, when they spend, do so not excessively or sparingly but are ever, between that, [justly] moderate (Q.S 25: 67) QS. Al-Isra’ : 29 . And do not make your hand [as] chained to your neck or extend it completely and [thereby] become blamed and insolvent. v DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: My beloved parents : H. Asfaroni Asror, M.Ag and Hj.Zumronah, AH, S.Pd.I, love and respect are always for you. My Sister Zahrotul Mufidah, S.Hum. M.Pd, and Zatin Nada, AH. My brother M.Faiz Ali Musyafa’ and M. Hamidum Majid. My husband, M. Shobahus sadad, S.Th.I (endut, iyeng, ecek ) Thank you for the valuable efforts and contributions in making my education success. My classmates, FUPK 2011, “PK tuju makin maju, PK sab’ah makin berkah, PK pitu unyu-unyu.” We have made a history guys. -

SPRING 2019 Dean's List Emily Deann Abernathy Emmley Deanna

SPRING 2019 Dean’s List Lindsey Michelle Ballard Ann Bradshaw Russell Ballard Anna Joy Bramblett Emily Deann Abernathy Brittani B Ballew Drewcilla Joan Brandon Emmley Deanna Abernathy Alexis Banda Nicole Carolyn Brewer Katelyn Moriah Ackerman Ashley L Bankston Kaylee Alyssa Bright Araceli Acosta Julianne M Bankston Sterlin Aaron Brindle Jennifer Leigh Adair Diana C Barajas Chloe R Brinkley Aaron D Adams Clarisa Barragan Cristian Gerardo Brito Logan Cheyenne Adams Nicholas S Bartley Mary Margaret Britton Tyler Deion Adams Jelani Nkosi Barton Sarah Katherine Britton Hannah Brooke Adcock Katrina Basto Edna Lynn Brock Alma Aguilar Jordan Montana Baumgardner William T Brooker Gricelda Aguilar Desmond Chase Bean Landon Dane Brooks Johanna Aguilar Carrie Leighann Beard Lori S. Brooks Israel Agundis Kaitlin Bearden Zoe Willow Brooks Kabir Mateen Akmal Kayla Ann Bearden Raven Leah Broom Gabriel H Albee Savannah Michelle Bearden Pete Nicholas Brower Javier Ernesto Alfaro Breanna H Beavers Christine J Brown Sport Garrison Allmond Oscar M Becerra Christopher Michael Brown Kristina Valeria Almazan Scott Russell Beck Katie M Brown Angeles Altamirano Courtney Leigh Bell Kaytlyn Nicole Brown Laura Michelle Alton Jazbeck Belman Olivia H Brown Diego Alexis Alvarado Ruiz Sabrina N Benoit Trevor Austin Brown Stephanie Alvarez David Berrospi Ashley Elizabeth Brownell Lozan A Amedi Andrew Jeffrey Besh Henley Lauren Brueckner Jordan Dustin Anderson McKinsey T Bettis Alissa Hope Brunner Marc Blaine Anderson Ciara Lynn Biggins Elizabeth A Bryan Felisha Caylen -

2020-2021 Catalog Contributing To

Georgia Military College 2020-2021 Catalog Contributing To Student Success! Stone Mountain Fairburn Fayetteville Madison Augusta Milledgeville Zebulon Sandersville Warner Robins Dublin Eastman Columbus Global Online Albany College Valdosta www.gmc.edu Published by the Academic Affairs Administration Table of Contents WELCOME .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 A Letter from the President ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 A Letter from the Senior VP, Chief Academic Officer, and Dean of Faculty ........................................................................... 14 2020-2021 ACADEMIC CALENDAR ........................................................................................................................................................... 15 Four Term Calendar (MNC) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Milledgeville Online (MLO) .................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Five Term Calendar (CMP) ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Skins and the Impossibility of Youth Television

Skins and the impossibility of youth television David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays, can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. In 2007, the UK media regulator Ofcom published an extensive report entitled The Future of Children’s Television Programming. The report was partly a response to growing concerns about the threats to specialized children’s programming posed by the advent of a more commercialized and globalised media environment. However, it argued that the impact of these developments was crucially dependent upon the age group. Programming for pre-schoolers and younger children was found to be faring fairly well, although there were concerns about the range and diversity of programming, and the fate of UK domestic production in particular. Nevertheless, the impact was more significant for older children, and particularly for teenagers. The report was not optimistic about the future provision of specialist programming for these age groups, particularly in the case of factual programmes and UK- produced original drama. The problems here were partly a consequence of the changing economy of the television industry, and partly of the changing behaviour of young people themselves. As the report suggested, there has always been less specialized television provided for younger teenagers, who tend to watch what it called ‘aspirational’ programming aimed at adults. Particularly in a globalised media market, there may be little money to be made in targeting this age group specifically. -

Week 6 Scorecard

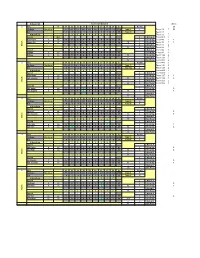

5/13/2021 Scorecard (Back 9) Skins 1 Hole In 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points 13 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #1 7 Team #1 7 33 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #7 Team #7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #2 7 Team #1 -17 Net 2 Match A Team #21 2 Nick Fischer 1 38 4 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 5 39 1 Show Up Team #3 2 1 h c Deacon Jim 2 37 4 5 4 5 4 4 4 4 5 39 78 1 Show Up Team #5 7 1 t a -1 3 2 Match B Team #6 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 75 1 Net Total Team #8 7 Team #7 -1 1 1 1 1 4 Match A Team #4 5 A-Player 5 35 5 6 4 4 5 3 4 4 5 40 Show Up Team #9 4 B-Player 6 35 5 5 5 4 5 3 5 4 4 41 81 Show Up Team #12 4 -1 1 1 1 1 4 11 Match B Team #20 5 78 Net Total Team #13 4 2 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Team #15 5 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #2 7 Team #14 5 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #21 2 Team #19 4 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #16 2 Team #2 -9 2 Match A Team #18 7 Kerry Brown 7 34 5 6 5 5 4 4 5 3 4 41 1 Show Up Team #17 6 1 h c Tom Jennings 8 34 4 5 5 4 5 3 7 3 6 42 83 1 Show Up Team #22 3 1 t a -9 1 1 15 2 Match B Team #23 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 68 1 Net Total Team #24 1 Team #21 -9 Match A Phil Hoefert 7 38 6 6 5 4 5 4 5 5 5 45 1 Show Up 1 Gary Osborne 7 34 5 7 5 3 5 4 4 4 4 41 86 1 Show Up 1 -11 14 Match B 72 Net Total 3 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #3 2 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #5 7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #3 -23 Match A Steve Hill 2 41 4 5 6 5 5 4 7 3 4 43 1 Show Up 1 h c Mike -

Fruit Candies Enriched with Grape Skin Powders: Physicochemical Properties

LWT - Food Science and Technology 62 (2015) 569e575 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect LWT - Food Science and Technology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/lwt Fruit candies enriched with grape skin powders: physicochemical properties * Carola Cappa, Vera Lavelli, Manuela Mariotti Department of Food, Environmental and Nutritional Sciences (DeFENS), Universita degli Studi di Milano, via G. Celoria 2, 20133 Milan, Italy article info abstract Article history: This study investigated the effect of addition of grape skins (GS) on a fruit candy having a gel-like Received 27 January 2014 structure. GS from Barbera, a red grape (Vitis vinifera L.) variety, were processed into powders through Received in revised form milling and sieving to obtain three fractions having different particle sizes. Three fruit candy types added 22 July 2014 with GS fractions and a reference candy (without GS) were produced and analysed during the dehy- Accepted 25 July 2014 dration process, mainly in terms of moisture, soluble solids, water activity, polyphenol contents, ferric Available online 4 August 2014 reducing antioxidant power, colour and texture. The fortification with GS powders increased the anthocyanin, flavonol and procyanidin contents of the candies, resulting in an increased antioxidant Keywords: fi Antioxidants activity, which remained stable during processing. Furthermore, the bre-enriched candies exhibited Dietary fibre good textural properties. In general, the addition of GS promoted the reduction of the processing time, Texture the replacement of a significant amount of fruit puree with a low-cost and high-nutritional winemaking Vitis vinifera L. by-product, as well as the delivery of beneficial compounds, thus highlighting the high potentialities Confectionery associated with the use of GS in the confectionery industry. -

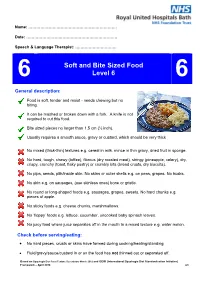

6 Soft and Bite Sized Food Level 6

Name: ………………………………………………………… Date: ……………………………………………..…………… Speech & Language Therapist: …………………………. Soft and Bite Sized Food 6 Level 6 6 General description: Food is soft, tender and moist - needs chewing but no biting. It can be mashed or broken down with a fork. A knife is not required to cut this food. Bite sized pieces no larger than 1.5 cm (½ inch). Usually requires a smooth sauce, gravy or custard, which should be very thick No mixed (thick-thin) textures e.g. cereal in milk, mince in thin gravy, dried fruit in sponge. No hard, tough, chewy (toffee), fibrous (dry roasted meat), stringy (pineapple, celery), dry, crispy, crunchy (toast, flaky pastry) or crumbly bits (bread crusts, dry biscuits). No pips, seeds, pith/inside skin. No skins or outer shells e.g. on peas, grapes. No husks. No skin e.g. on sausages, (use skinless ones) bone or gristle. No round or long-shaped foods e.g. sausages, grapes, sweets. No hard chunks e.g. pieces of apple. No sticky foods e.g. cheese chunks, marshmallows. No ‘floppy’ foods e.g. lettuce, cucumber, uncooked baby spinach leaves. No juicy food where juice separates off in the mouth to a mixed texture e.g. water melon. Check before serving/eating: • No hard pieces, crusts or skins have formed during cooking/heating/standing. • Fluid/gravy/sauce/custard in or on the food has not thinned out or separated off. Based on Dysphagia Diet Food Texture Descriptors March 2012 and IDDSI (International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative) Framework – April 2018 Please turn over for more information Soft and Bite Sized Food 6 Level 6 6 All Level 6 foods must be chopped into bite sized pieces (1.5cm/½ inch) before eating. -

Kaya Scodelario: from Teen Drama to Tinseltown

12 FEATURE artslondonnews.com Friday 00 November 2012 Kaya Scodelario: From teen drama to Tinseltown ‘’I went through a year of hating my- self at secondary school, I was bul- lied to the point of having to change schools because it got so bad’’ It seems the skins star, now age 23, al- most has bullies to thank for her rise to fame and her suc- sess. The English born beauty has now bro- ken America and is Kaya as Effy Stonem in Skins with co-starts Luke Pasqualino and Jack O’ Connell happily married. She charts much of her The Scorch Trials’ as 14 for a role in the her character being success down to a strong female lead gritty British teen dra- diagnosed with a Skins audition tak- ‘Teresa Agnes’. ma claiming that act- case of psychotic de- en on the off chance ing was the only thing pression (Series 4) after having to flee ‘’I could never see she had confidence Kaya commented schools due to cruel myself just playing in. saying she enjoyed bullies. Scodelar- the girlfriend or the depicting ‘the realistic io, born to a Brazil- love conquest, I Scodelario amassed trials and challenges’ ian mother, and an like meaty roles and success through her that Effy faced. English father, is intelligent roles for 4 years in Skins tak- best known for her women’’ ing on a whole range ‘I just want to keep breakthrough perfor- of challenging and working consist- mance as the elusive Despite having dys- thought provoking is- ently and do the job ‘Effy (Elizabeth) Sto- lexia and having ma- sues including trouble that I love, even if nem’ in Skins and jor -

Transdermal Permeation of Drugs in Various Animal Species

pharmaceutics Review Transdermal Permeation of Drugs in Various Animal Species Hiroaki Todo 1,2 ID 1 Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Josai University, 1-1 Keyakidai, Sakado, Saitama 350-0295, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Josai University, 1-1 Keyakidai, Sakado, Saitama 350-0295, Japan Received: 31 July 2017; Accepted: 28 August 2017; Published: 6 September 2017 Abstract: Excised human skin is utilized for in vitro permeation experiments to evaluate the safety and effect of topically-applied drugs by measuring its skin permeation and concentration. However, ethical considerations are the major problem for using human skin to evaluate percutaneous absorption. Moreover, large variations have been found among human skin specimens as a result of differences in age, race, and anatomical donor site. Animal skins are used to predict the in vivo human penetration/permeation of topically-applied chemicals. In the present review, skin characteristics, such as thickness of skin, lipid content, hair follicle density, and enzyme activity in each model are compared to human skin. In addition, intra- and inter-individual variation in animal models, permeation parameter correlation between animal models and human skin, and utilization of cultured human skin models are also descried. Pig, guinea pig, and hairless rat are generally selected for this purpose. Each animal model has advantages and weaknesses for utilization in in vitro skin permeation experiments. Understanding of skin permeation characteristics such as permeability coefficient (P), diffusivity (D), and partition coefficient (K) for each skin model would be necessary to obtain better correlations for animal models to human skin permeation. -

Loss of Self in Psychosis

LOSS OF SELF IN PSYCHOSIS In Loss of Self in Psychosis: Psychological Theory and Practice Simon Jakes takes a critical look at contemporary approaches to the psychology of psychosis. In doing so, he explores how these vastly different approaches, as well as our numerous conceptual- isations of schizophrenia, work to reduce the effectiveness of CBT as a treatment. Four different psychological approaches to psychosis are examined in the first part of this book, as well as the development of CBT for psychosis and the theory behind this. In the second part, he describes the therapy of some clients and suggests that incorporating ideas from some of the different theories of psychosis in the same treatment may be beneficial. Using extended examples from clinical practice over the past 20 years to illuminate his theories, Loss of Self in Psychosis: Psychological Theory and Practice will prove to be thought-provoking reading for clinical psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals working with this client group. Simon Jakes is a clinical psychologist at the Bankstown Community Mental Health Team in South Western Sydney, New South Wales. He is also in private practice. LOSS OF SELF IN PSYCHOSIS Psychological Theory and Practice Simon Jakes First published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Simon Jakes The right of Simon Jakes to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.