The Art of Confectionery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Articles All Faculty Scholarship Spring 1-1-2003 Wendy A. Woloson. Refined aT stes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2003). Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America. Winterthur Portfolio, 38(1), 72–76. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/70 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72 Winterthur Portfolio 38:1 upon American material life, the articles pri- ture, anthropologists, and sociologists as well as marily address objects and individuals within the food historians. It also serves as a vivid account Delaware River valley. Philadelphia, New Jersey, of the emergence of consumer culture in gen- and Delaware are treated extensively. Outlying eral, focusing on the democratization of once- Quaker communities, such as those in New En- expensive sweets due to new technologies and in- gland, North Carolina, and New York state, are es- dustrial production and their shift from symbols sentially absent from the study. Similarly, the vol- of power and status to indulgent ephemera best ume focuses overwhelmingly upon the material life left to women and children. -

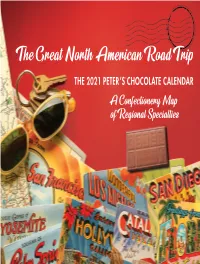

A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties

The Great North American Road Trip THE 2021 PETER’S® CHOCOLATE CALENDAR A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties One of the great pleasures of domestic travel in North America is to see, hear and taste the regional differences that characterize us. The places where we live help shape the way we think, the way we talk and even the way we eat. So, while chocolate has always been one of the world’s great passions, the ways in which we indulge that passion vary widely from region to region. In this, our 2021 Peter’s Chocolate Calendar, we’re celebrating the great love affair between North Americans and chocolate in all its different shapes, sizes, and flavors. We hope you’ll join us on this journey and feel inspired to recreate some of the specialties we’ve collected along the way. Whether it’s catfish or country-fried steak, boiled crawfish or peach cobbler, Alabama cuisine is simply divine. Classic southern recipes are as highly prized as family heirlooms and passed down through the generations in the Cotton State. This is doubtless how the confection known as Southern Divinity built its longstanding legacy in this region. The balanced combination of salty and sweet is both heavenly and distinctly Southern. Southern Divinity Southern Divinity Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat Ingredients: December February 1 001 2 002 2 Egg Whites S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 17 oz Sugar 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 56 6 oz Light Corn Syrup 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 4 oz Water 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 1 tbsp Vanilla Extract 27 28 29 30 31 28 New Year’s Day 6 oz Coarsely Chopped Pecans, roasted & salted Peter’s® Marbella™ Bittersweet Chocolate, 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 for drizzling Directions: Beat egg whites in a stand mixer until stiff National Chocolate peaks form. -

Caramelization of Sugar

Caramelization of Sugar Sugar is caramelized when it is melted into a clear golden to dark brown syrup, reaching a temperature from 320 to 356 degrees F. It goes through many stages which are determined by the recipe being made. Using a pure copper sugar pan will allow total control of the sugar and avoid crystallization of sugar. At 338 degrees F, the sugar syrup begins to caramelize creating an intense flavor and rich color, from light and clear to dark brown. Depending upon when the cooking stops and it cools and hardens, caramel textures can range from soft to brittle. A soft caramel is a candy made with caramelized sugar, butter and milk. Crushed caramel is used as a topping for ice cream and other desserts. When it cracks easily and is the base for nut brittles. To start, add some water to dry sugar in a pure copper sugar pan, stirring, until it reaches the consistency of wet sand. An interfering agent, such as lemon juice will help prevent re-crystallization because of the acid in it. Instead of using lemon juice, you could add acidity with vinegar, cream of tartar or corn syrup. Always start with a very clean pan and utensils. Any dirt or debris can cause crystals to form around it. Heat the pure copper sugar pan over a medium flame. As the sugar melts, you can wash down the sides of a pan with a wet brush, which also prevents crystallization by removing any dried drops of syrup that might start crystals. As the caramel heats, it colors in amber shades from light to deep brown. -

WEEKEND KITCHEN RECIPE SHEET 8Th November 2015 Charlotte

WEEKEND KITCHEN RECIPE SHEET 8th November 2015 Charlotte White Spiced Carrot Cake with Cream Cheese Frosting This is a recipe that I have adapted over the years from a Delia Smith book! I love Delia’s recipes but found that the resulting cake from her Carrot Cake recipe was not quite big enough for my liking – I do like to provide generous portions! I have also added Orange Extract to this recipe as it gives a much stronger flavour than orange zest and is far less messy to use. Good quality natural Orange Extract is divine. I always couple my Carrot Cake with an American inspired Cream Cheese Frosting. This is essentially just buttercream made with half butter and half cream cheese but the result is a wonderful creamy texture that holds up to being spread all over the cake or piped on cupcakes too. Carrot Cake Ingredients: 350g Dark Brown Soft Sugar 300ml Sunflower Oil 4 Large Eggs 1 tsp Orange Extract 400g Self-Raising Flour 6 tsp Mixed Spice 2 tsp Bicarb of Soda 400g Grated Carrot 200g Sultanas 100g Desiccated Coconut Oven temp = 180C/ Gas Mark 4 Whisk the sugar, oil and eggs until combined. You will need to whisk until the sugar is all dissolved and this should take 3 minutes or so. Add the orange extract. Combine the flour, mixed spice and bicarb in a separate bowl and fold this into the wet ingredients a third at a time. Add the carrot, sultanas and coconut to the cake mixture and fold these through until all are well covered. -

Charlotte May 21- Menu Update

Takin' care of biscuits STARTERS French toast bites $5.50 Brioche-based French toast bites, fried and tossed in cinnamon sugar served with cream cheese icing & praline sauce Pig candy bacon bites $5 Applewood-smoked bacon bites with a candy glaze Fried green tomatoes $7 Fried green tomatoes topped with lettuce, red tomatoes, remoulade, and bacon onion jam Seasonal beignets $7 Ask server for details. BENEDICTS SPECI ALTIES Eggs Cochon* $15 BBq shrimp & grits $15.50 Slow-cooked, apple-braised pork debris served over a buttermilk Gulf shrimp sauteed with pork tas so, bell pepper, red onion, beer & biscuit, topped with two poached eggs, finished with hollandaise rosemary butter reduction, over creamy stone-ground grits served with a buttermilk biscuit Chicken St. Charles* $15 Fried chicken breast served over a buttermilk biscuit, topped with Migas $12 two poached eggs, finished with a pork tasso cream sauce A Tex-Mex egg scramble with pico de gallo, spicy chorizo, and pepper jack cheese over crispy tortilla chips served with avocado, bayou Shrimp* $15.50 a side of chipotle sour cream, and pico de gallo Gulf shrimp sauteed with pork tasso and creole tomato sauce Try it with crawfish +$5 served over two poached eggs, fried green tomatoes and a Breakfast Tacos (VEG) $12 buttermilk biscuit 3 grilled flour tortillas filled with a scramble of eggs, pico de gallo, corned beef* $15.50 pepper jack cheese, chipotle sour cream and avocado, served with a Housemade corned beef ha sh served over a buttermilk biscuit, side of black beans and rice topped -

5Lb. Assortment

Also available in Red 5LB. ASSORTMENT Pecan or Almond Törtél Caramel Pilgrim Hat Our slightly chewy caramel Creamy, extra soft caramel covering roasted pecans or in dark chocolate. almonds. Milk or dark chocolate. English Toffee Irish Toffee Chewy, ”melt-in-your-mouth” Baton-shaped, buttery toffee. toffee, dipped in milk chocolate. The Irish is brittle and crunchy. Dipped in milk or dark chocolate. Hazelnut Toffee Buttery brittle toffee with roasted Good News Mint Caramel chopped hazelnuts. Dipped in Creamy mint caramel dipped milk or dark and sprinkled with in milk chocolate only. caramelized hazelnuts. ASSORTMENT 5 LB. (108 PC.) - ASSORTMENT In response to our customers request, we have created an extra large assortment! This includes: Soft a’ Silk Caramel, Hazelnut Toffee, Solid Belgian Chocolate, Peanut Butter Smooth and Crunch, Pecan and Almond Törtéls, Caramel Pilgrim Hats, Good News Mint Caramel, Irish and English Toffees, Hazelnut Praline, as well as, Salty Brits, Coconut Igloos, Marzipan and Cherry Hearts. Packaged in one of our largest hinged box and includes our wired gift bow. $196.75 (108 pc.) Toll Free: 800-888-8742 | Local: 203-775-2286 1 Fax: 203-775-9369 | [email protected] Almond Toffee Peanut Butter Pattie Brittle and crunchy with roasted Our own smooth peanut butter almonds. Milk or dark chocolate. shaped into round patties. Dipped in milk chocolate. Hazelnut Praline Hazelnut praline (Gianduja) is Solid Belgian Chocolate ASSORTMENT THE BRIDGEWATER made from finely crushed filberts Our blend of either dark or milk mixed with milk chocolate. Dipped chocolate. in milk or dark. Peanut Butter Crunch Our own creamy peanut butter Soft a’ Silk Caramel with the addition of chopped Soft and creamy caramel dipped caramelized nuts. -

Isaiah Davenport House Volunteer Newsletter December 2009 236-8097

Isaiah Davenport House Volunteer Newsletter December 2009 www.davenporthousemuseum.org 236-8097 The Happy Condition DAVENPORT HOUSE CALENDAR November 30 at 10 a.m. and The man who, for life, is blest with a Tuesday, December 1 – Wreath Tuesday, December 1 at 2 p.m. wife, decorating We could use some docents to help Is sure, in a happy condition: 2 p.m. – Review and refresher with the Holly Jolly tours which take Go things as they will, she’s fond of for docents of December inter- place on all nights between Novem- him still, pretation ber 27 and December 23. Old She’s comforter, friend and physician. November 30 through December Town Trolley has a wonderful crew 4 in the afternoon – Prep for of docents and the DH and OTT Pray where is the joy, to trifle and toy! Holiday Bazaar split tour guide duties. Some nights Yet dread some disaster from beauty! Friday, December 4 from 5 to 7 there are two or more trolleys and But sweet is the bliss of a conjugal kiss, p.m. – Annual Christmas Party on Monday, December 7 there will Where love mingles pleasure with – y’all come! be 5! Jamie, Jeff and Raleigh set up duty. Saturday, December 5 from 10 and give tours. So far Jody Leyva, a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sunday, Maria Sanchez and Anthony San- One extravagant Miss won’t cost a December 6 from 1 to 5 p.m. chez have agreed to help as well. man less – Holiday Bazaar at the Ken- Any others of you who can help us Than twenty good wives that are sav- nedy Pharmacy spread the Christmas cheer!? ing; Tuesday, December 8 all day – For, wives they will spare, that their Alliance for Response (Disaster SHOP NEWS : children may share, Planning) Workshop in Savan- - REMEMBER YOUR But Misses forever are craving. -

A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770 Mollie C. Malone College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malone, Mollie C., "A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626149. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0rxz-9w15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mollie C. Malone 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 'JYIQMajl C ^STIclU ilx^ Mollie Malone Approved, December 1998 P* Ofifr* * Barbara (farson Grey/Gundakerirevn Patricia Gibbs Colonial Williamsburg Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR’S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 17 CONCLUSION 45 APPENDIX 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 i i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank Professor Barbara Carson, under whose guidance this paper was completed, for her "no-nonsense" style and supportive advising throughout the project. -

10229119.Pdf

T.C. ĠSTANBUL AYDIN ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ FEN BĠLĠMLERĠ ENSTĠTÜSÜ SÜTLÜ TATLI ÜRETĠMĠ YAPAN BĠR ĠġLETMEDE ISO 22000 GIDA GÜVENLĠĞĠ YÖNETĠM SĠSTEMĠNĠN ĠNCELENMESĠ YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Burcu ÇEVĠK Gıda Güvenliği Anabilim Dalı Gıda Güvenliği Programı Tez DanıĢmanı Prof. Dr. Haydar ÖZPINAR Aralık, 2018 ii T.C. ĠSTANBUL AYDIN ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ FEN BĠLĠMLERĠ ENSTĠTÜSÜ SÜTLÜ TATLI ÜRETĠMĠ YAPAN BĠR ĠġLETMEDE ISO 22000 GIDA GÜVENLĠĞĠ YÖNETĠM SĠSTEMĠNĠN ĠNCELENMESĠ YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Burcu ÇEVĠK (Y1613.210011) Gıda Güvenliği Anabilim Dalı Gıda Güvenliği Programı Tez DanıĢmanı Prof. Dr. Haydar ÖZPINAR Aralık, 2018 ii iv YEMĠN METNĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak sunduğum „‟Sütlü Tatlı Üretimi Yapan Bir ĠĢletmede TS EN ISO 22000 Gıda Güvenliği Yönetim Sisteminin Ġncelenmesi‟‟ adlı tezin proje safhasından sonuçlanmasına kadarki bütün süreçlerde bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düĢecek bir yardıma baĢvurulmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin Bibliyografya‟da gösterilenlerden oluĢtuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanılmıĢ olduğunu belirtir ve onurumla beyan ederim. ( / /2018) Burcu ÇEVĠK v vi ÖNSÖZ Yüksek lisans eğitimim boyunca benden bilgilerini, deneyimlerini ve yardımlarını esirgemeyen baĢta değerli tez danıĢmanım Prof. Dr. Haydar ÖZPINAR‟a tez çalıĢmam boyunca yardımlarını esirgemeyen, Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Ayla Ünver ALÇAY‟a ve Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Burcu Çakmak SANCAR‟a çalıĢmalarımda her an yanımda olduğu için değerli arkadaĢlarım Gamze BENLĠKURT ve Çiğdem SÖKMEN‟e Hayatım boyunca benden maddi ve manevi desteklerini esirgemeyen, varlıklarıyla beni onurlandıran -

Recipe Except Substitute 1/4 Cup Cocoa for 1/4 Cup of the Flour (Stir to Blend with Flour and Sugar) and Omit Almond Flavoring

Almond Filling Grouping: Pastries, basic mixes Yield: 10 pound Serving: 30 Ingredient 1 #10 can Almond Paste 1/2 #10 can Sugar 1/2 #10 can Raw Sliced Almonds 16 each Eggs, possibly 18 1 cup Brandy / Amaretto 10 cup Cake Crumbs Preparation 1. Cream almond paste and sugar with a paddle until smooth. 2. Add the raw almonds, eggs, and liquor, mixing until just blended. 3. Add the cake crumbs, adjusting by eye to consistency. Almond Dough Grouping: Pastries, amenities, Yield: 0.5 sheet pan Serving: OR 9 pounds 6 ounces Ingredient 1 pound 8 ounce Sugar 2 pound 4 ounce Butter 12 ounce Egg 3 pound 12 ounce Pastry flour Sifted 1 pound 2 ounce Almond flour Sifted Preparation 1. Cream together butter and sugar. Slowly incorporate eggs. 2. Add flours all at once and mix only until incorporated. New England Culinary Institute, 2006 1 Almond Macaroon (Amaretti) Grouping: Pastries, amenities, Yield: 100 Cookies Serving: Ingredient 3 1/2 pound Almond paste 2 1/2 pound Sugar 2 ounce Glucose 1/2 quart Egg whites Couverture Preparation 1. Soften almond paste with a little egg white. Add sugar and glucose then incorporate the rest of the whites. Pipe round shapes, moisten, and dust with powdered sugar before baking. For Amaretti, allow to dry overnight, THEN dust with powdered sugar and press into star before 2. For walnut macaroons, replace 1 1/2 lbs. Almond paste with very finely ground walnuts, and increase glucose to 3 oz. Let stand overnight before piping oval shapes. Top with half a walnut. -

January 2016

Kansas State University Research & Extension Newsletter Title January 2016 It’s Cookie Time! Inside this issue: To change the texture and color, try these tips, one at a time, from the book Equipment to 2 make Candy CookWise by Shirley O. Corriher: For More Spread Candy Thermom- 2 eters Use butter Increase liquid 1-2 tablespoons Oatmeal 2 Increase sugar 1-2 tablespoons Popcorn 3 Warm cold ingredients to room tem- perature, don’t refrigerate dough Fats to make 3 There are thousands of cookie recipes in For More Puff Candy a variety of shapes, sizes, textures, and Use shortening flavors. During the holidays, cookies What are Sugar 3 are a special treat and everyone has a Use cake flour Plums? favorite. Let’s see how a traditional Reduce sugar a couple tablespoons chocolate chip cookie can be altered for Spaghetti 4 Use all baking powder a different look. Use cold ingredients or refrigerate Transporting 4 Chocolate chip manufacturers have dough Food Safely made special holiday shapes. Simply For More Tenderness replace the regular chips with these fan- Use cake flour cy chips. Try adding some frosting and colored sprinkles for extra sparkle. Add a few tablespoons fat or sugar Now on Facebook, Twitter and Pinter- est! On Facebook— www.facebook.com /KSREfoodie 2016 Urban Food Systems Symposium On Twitter— @KSREfoodie Save the date for the cultural production, local Learn more about this On Pinterest— 2016 Urban Food System food systems distribution, event at www.pinterest.com Symposium! This event urban farmer education, www.urbanfoodsystemssy /ksrefoodie/ will be June 23-26, 2016 urban ag policy, planning mposium.org/. -

Ingredient Book 11-4-2020.Pdf

The following is a list of ingredients used in various recipes that are served to clients of Meals on Wheels as dictated through our menus. Regular and modified menus are approved by a registered dietitian to ensure proper nutrition for older adults. It is the client’s responsibility to ensure physician’s recommendations are followed. Every effort will be made to provide the selected menu, but occasionally there may be a substitution served due to circumstances beyond our control. Menus are subject to change. In addition, substitute ingredients may be used due to circumstances beyond our control with vendors. Exact serving sizes and detailed nutrition information is available upon request. For questions or concerns about the menu or for the most up to date ingredients please call Amber Goines at 740-681-5050. 11/4/2020 Beef BEEF, STRIP FAJITA SEASONED COOKED FROZEN SMARTSERVE INGREDIENTS BEEF, WATER, SEASONING [SALT, MALTODEXTRIN, SODIUM PHOSPHATE, GARLIC, SPICES, DISODIUM INOSINATE AND DISODIUM GUANYLATE, PAPAIN], VEGETABLE PROTEIN PRODUCT [SOY PROTEIN CONCENTRATE, ZINC OXIDE, NIACINAMIDE, FERROUS SULFATE, COPPER GLUCONATE, VITAMIN A PALMITATE, CALCIUM PANTOTHENATE, THIAMINE MONONITRATE B1, PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHLORIDE B6, RIBOFLAVIN B2, CYANOCOBALAMIN B12], CONTAINS 2 OR LESS OF THE FOLLOWING CANOLA OIL WITH TBHQ AND CITRIC ACID, DIMETHYLPOLYSILOXANE], BLACK PEPPER, DEXTROSE, SODIUM PHOSPHATE, YEAST EXTRACT, NATURAL FLAVOR. CONTAINS SOY BEEF, TOP INSIDE ROUND PACKER INGREDIENTS NOT AVAILABLE AT THIS TIME BEEF, PATTY GROUND STEAK 78/22 4:1 HOMESTYLE RAW FROZEN CLOUD THE CLOUD BEEF BEEF, BREADED STEAK COUNTRY FRIED LOW SALT COOKED FROZEN ADVANCE FOOD HEARTLAND BEEF BEEF, SALT, POTASSIUM AND SODIUM PHOSPHATE. BREADED WITH: ENRICHED BLEACHED WHEAT FLOUR ENRICHED WITH NIACIN, FERROUS SULFATE, THIAMINE MONONITRATE, RIBOFLAVIN, FOLIC ACID, SPICES, SALT, LEAVENING SODIUM ALUMINUM PHOSPHATE, SODIUM BICARBONATE, TORULA YEAST, SOYBEAN OIL, ONION POWDER.