LRB · Steven Shapin: Hedonistic Fruit Bombs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Almond Skins to Improve Nutritional and Functional Properties of Biscuits: an Example of Upcycling

foods Article Use of Almond Skins to Improve Nutritional and Functional Properties of Biscuits: An Example of Upcycling Antonella Pasqualone 1,* , Barbara Laddomada 2 , Fatma Boukid 3 , Davide De Angelis 1 and Carmine Summo 1 1 Department of Soil, Plant and Food Science (DISSPA), University of Bari Aldo Moro, Via Amendola, 165/a, I-70126 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (D.D.A.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Institute of Sciences of Food Production (ISPA), CNR, via Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] 3 Institute of Agriculture and Food Research and Technology (IRTA), Food Safety Programme, Food Industry Area, Finca Camps i Armet s/n, 17121 Monells, Catalonia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23 October 2020; Accepted: 16 November 2020; Published: 20 November 2020 Abstract: Upcycling food industry by-products has become a topic of interest within the framework of the circular economy, to minimize environmental impact and the waste of resources. This research aimed at verifying the effectiveness of using almond skins, a by-product of the confectionery industry, in the preparation of functional biscuits with improved nutritional properties. Almond skins were added at 10 g/100 g (AS10) and 20 g/100 g (AS20) to a wheat flour basis. The protein content was not influenced, whereas lipids and dietary fiber significantly increased (p < 0.05), the latter meeting the requirements for applying “source of fiber” and “high in fiber” claims to AS10 and AS20 biscuits, respectively. The addition of almond skins altered biscuit color, lowering L* and b* and increasing a*, but improved friability. -

Female Desire in the UK Teen Drama Skins

Female desire in the UK teen drama Skins An analysis of the mise-en-scene in ‘Sketch’ Marthe Kruijt S4231007 Bachelor thesis Dr. T.J.V. Vermeulen J.A. Naeff, MA 15-08-16 1 Table of contents Introduction………………………………..………………………………………………………...…...……….3 Chapter 1: Private space..............................................…….………………………………....….......…....7 1.1 Contextualisation of 'Sketch'...........................................................................................7 1.2 Gendered space.....................................................................................................................8 1.3 Voyeurism...............................................................................................................................9 1.4 Properties.............................................................................................................................11 1.5 Conclusions..........................................................................................................................12 Chapter 2: Public space....................……….…………………...……….….……………...…...…....……13 2.1 Desire......................................................................................................................................13 2.2 Confrontation and humiliation.....................................................................................14 2.3 Conclusions...........................................................................................................................16 Chapter 3: The in-between -

I HEDONISM in the QUR'a>N

HEDONISM IN THE QUR’A>N ( STUDY OF THEMATIC INTERPRETATION ) THESIS Submitted to Ushuluddin and Humaniora Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Strata-1 (S.1) of Islamic Theology on Tafsir Hadith Departement Written By: HILYATUZ ZULFA NIM: 114211022 USHULUDDIN AND HUMANIORA FACULTY STATE OF ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY WALISONGO SEMARANG 2015 i DECLARATION I certify that this thesis is definitely my own work. I am completely responsible for content of this thesis. Other writer’s opinions or findings included in the thesis are quoted or cited in accordance with ethical standards. Semarang, July 13, 2015 The Writer, Hilyatuz Zulfa NIM. 114211022 ii iii iv MOTTO QS. Al-Furqan: 67 . And [they are] those who, when they spend, do so not excessively or sparingly but are ever, between that, [justly] moderate (Q.S 25: 67) QS. Al-Isra’ : 29 . And do not make your hand [as] chained to your neck or extend it completely and [thereby] become blamed and insolvent. v DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: My beloved parents : H. Asfaroni Asror, M.Ag and Hj.Zumronah, AH, S.Pd.I, love and respect are always for you. My Sister Zahrotul Mufidah, S.Hum. M.Pd, and Zatin Nada, AH. My brother M.Faiz Ali Musyafa’ and M. Hamidum Majid. My husband, M. Shobahus sadad, S.Th.I (endut, iyeng, ecek ) Thank you for the valuable efforts and contributions in making my education success. My classmates, FUPK 2011, “PK tuju makin maju, PK sab’ah makin berkah, PK pitu unyu-unyu.” We have made a history guys. -

Download Guidelines and Role Descriptions For

Book of Projects 2012 ProectsBook12ofScript&Pitch Audience Design Writer’s Room The Pixel Lab FrameWork AdaptLab 1 Book of Projects 2012 ProectsBook12ofScript&Pitch Audience Design Writer’s Room The Pixel Lab FrameWork AdaptLab TorinoFilmLab has reached its fifth edition this year, Now that we are 5 years old, I must think of and it is a pleasure to celebrate together with those what I hope we can achieve for our 10th birthday. who have supported us since the very beginning: TorinoFilmLab is on the map now, but what is most Regione Piemonte, Comune di Torino and Ministero important is that we become, more and more, a per i Beni e le Attività culturali. community of filmmakers from all around the world, sharing experiences, knowledge, successes, failures, In these years, TorinoFilmLab has grown steadily, friendships, collaborations, projects, ideas…. adding programmes, activities and partners from all TorinoFilmLab works to offer opportunities, to create over Europe and the world. What in 2008 started a space were professionals in the cinema and media with 2 training activities, a co-production market and world can - if not find all they need, at least find a production fund, now runs 6 training activities that useful directions. We have worked hard and will try still all come together (except Interchange, that finds even harder in the next years. I say we, not because I a dedicated platform at the DFC during the Dubai deserve pluralis maiestatis, but because TorinoFilmLab International Film Festival) for the TFL Meeting Event is already a community, where staff, tutors and in Torino, during the Torino Film Festival. -

TWC009 014 Michel Rolland.Indd 70

COLLECTION WEALTH THE | xxx GENIUS OF THE BOTTLE Michel Rolland’s presence is felt throughout the world of wine and he has arguably changed forever the vinification process, yet his scientific techniques have become highly controversial. Richard Middleton speaks to an oenological revolutionary. 70 TWC009_014 Michel Rolland.indd 70 18/9/08 14:57:20 lifestyle veryone seems to agree, whether you are speaking to a fan or a critic Critics of Rolland argue this is the problem. He is, to them, an all- that, over his 35 year career, Michel Rolland has changed the face consuming global force, reducing the art and finesse of wine production to | of the multi-billion pound wine industry. With his hotly debated a mere formula. THE E WEALTH techniques for transforming dwindling vineyards into productive, and of The controversy and Rolland’s celebrity status resulted in one of the course, profitable concerns, he has positioned himself as a wine guru. But his wine world’s definitive big-screen moments, Jonathan Nossiter’s 2004 COLLECTION projects certainly pay financial dividends. And he’s stirred up a fair amount film Mondovino. In the film Nossiter explored just what made Rolland’s of controversy along the way. techniques so controversial. He contrasted converts’ adoration with the ‘I came into the wine business in 1973 and at that time everything was opinions of those who argued that producers’ are too easily won over by wrong because the 60s and 70s were only oriented to production, not ‘Parker-friendly wines (controversial wine critic Robert Parker). quality,’ Rolland says. -

Declawing Ostrich Chicks (Struthio Camelus) to Minimize Skin Damage

South African Journal of Animal Science 2002, 32(3) 192 © South African Society for Animal Science Declawing ostrich (Struthio camelus domesticus) chicks to minimize skin damage during rearing A. Meyer1,3,#, S.W.P. Cloete2 C.R. Brown3,* and S.J. van Schalkwyk1 ¹Klein Karoo Agricultural Development Centre, P.O. Box 351, Oudtshoorn 6620, South Africa ²Elsenburg Agricultural Development Centre, Private Bag X1, Elsenburg 7607, South Africa ³School of Animal, Plant & Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Wits 2050, South Africa Abstract Leather is one of the main products derived from ostrich farming. Current rearing practices lead to a high incidence of skin damage, which decreases the value of ostrich skins. In the emu and poultry industry, declawing is commonly practiced to reduce skin damage and injuries. We consequently investigated declawing of ostrich chicks as a potential management practice to minimize skin lesions that result from claw injuries. A group of 140 day-old ostriches was declawed and a second group of 138 chicks served as the control. The two groups were reared separately to slaughter, but were rotated monthly between adjacent feedlot paddocks to minimize possible paddock effects. Overall, the declawed group had fewer scratch and kick marks on the final processed skin than the control group, which resulted in the proportion of first grade skins in the declawed group being more than twice that of the control group. Behavioural observations at nine and 13 months of age indicated that declawing resulted in no impairment in locomotive ability or welfare. There was a tendency for the declawed group to have higher average live weights towards the end of the growing-out phase that resulted in a 3.7% higher average skin area at slaughter than in the control group. -

SPRING 2019 Dean's List Emily Deann Abernathy Emmley Deanna

SPRING 2019 Dean’s List Lindsey Michelle Ballard Ann Bradshaw Russell Ballard Anna Joy Bramblett Emily Deann Abernathy Brittani B Ballew Drewcilla Joan Brandon Emmley Deanna Abernathy Alexis Banda Nicole Carolyn Brewer Katelyn Moriah Ackerman Ashley L Bankston Kaylee Alyssa Bright Araceli Acosta Julianne M Bankston Sterlin Aaron Brindle Jennifer Leigh Adair Diana C Barajas Chloe R Brinkley Aaron D Adams Clarisa Barragan Cristian Gerardo Brito Logan Cheyenne Adams Nicholas S Bartley Mary Margaret Britton Tyler Deion Adams Jelani Nkosi Barton Sarah Katherine Britton Hannah Brooke Adcock Katrina Basto Edna Lynn Brock Alma Aguilar Jordan Montana Baumgardner William T Brooker Gricelda Aguilar Desmond Chase Bean Landon Dane Brooks Johanna Aguilar Carrie Leighann Beard Lori S. Brooks Israel Agundis Kaitlin Bearden Zoe Willow Brooks Kabir Mateen Akmal Kayla Ann Bearden Raven Leah Broom Gabriel H Albee Savannah Michelle Bearden Pete Nicholas Brower Javier Ernesto Alfaro Breanna H Beavers Christine J Brown Sport Garrison Allmond Oscar M Becerra Christopher Michael Brown Kristina Valeria Almazan Scott Russell Beck Katie M Brown Angeles Altamirano Courtney Leigh Bell Kaytlyn Nicole Brown Laura Michelle Alton Jazbeck Belman Olivia H Brown Diego Alexis Alvarado Ruiz Sabrina N Benoit Trevor Austin Brown Stephanie Alvarez David Berrospi Ashley Elizabeth Brownell Lozan A Amedi Andrew Jeffrey Besh Henley Lauren Brueckner Jordan Dustin Anderson McKinsey T Bettis Alissa Hope Brunner Marc Blaine Anderson Ciara Lynn Biggins Elizabeth A Bryan Felisha Caylen -

Southern France Roberson Wine Tasting

ROBERSON WINE PRESENTS THE WINES OF SOUTHERN FRANCE WAW Page 53 Map 10 France Regional CORSE 7 Ajaccio N International boundary Département boundary Chief town of département VDQS Centre of VDQS AC not mapped elsewhere Centre of AC area Champagne (pp.78–81) Loire Valley (pp.118–25) Burgundy (pp.54–77) Jura and Savoie (pp.150–51) Rhône (pp.130–39) Southwest (pp.112–14) THE WINES OF Dordogne (p.115) SOUTHERN Bordeaux (pp.82–111) FRANCE Languedoc-Roussillon (pp.140–45) Provence (pp.146–48) Alsace (pp.126–29) Corsica (p.149) Other traditional vine-growing areas Proportional symbols Area of vineyard per département in thousands of hectares (no figure given if area <1000 hectares) LANGUEDOC PROVENCE 1:3,625,000 Km 0 50 100 150 Km ROUSSILLONMiles 0 50 100 Miles The Languedoc and Roussillon constitutes the world’s largest wine growing region, with a total of over 700,000 acres under vine (Provence adds another 70,000 or so) and for many years these three regions were the source of a great deal of France’s ‘wine lake’, making wine that nobody wanted to drink, let alone part with their hard earned francs for. The last decade has seen all of that change, and what was once the land of plonk is now one of the most exciting regions in the world of wine, with innovative vignerons producing both artisanal limited production cuvées and branded wines of vastly improved quality. The array of styles from this fascinating region offers wonderful diversity for the enthusiast - from dry and mineral white wines through crisp rosés to deep, structured red wines and on to unctuous sweet and fortified wines. -

2020-2021 Catalog Contributing To

Georgia Military College 2020-2021 Catalog Contributing To Student Success! Stone Mountain Fairburn Fayetteville Madison Augusta Milledgeville Zebulon Sandersville Warner Robins Dublin Eastman Columbus Global Online Albany College Valdosta www.gmc.edu Published by the Academic Affairs Administration Table of Contents WELCOME .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 A Letter from the President ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 A Letter from the Senior VP, Chief Academic Officer, and Dean of Faculty ........................................................................... 14 2020-2021 ACADEMIC CALENDAR ........................................................................................................................................................... 15 Four Term Calendar (MNC) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Milledgeville Online (MLO) .................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Five Term Calendar (CMP) ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Katalog 2019 22./23

Die ganze Welt des Weins im MAK MESSE KATALOG 2019 22./23. NOVEMBER FR 22.11.2019 | 15-21 UHR SA 23.11.2019 | 15-21 UHR NOTIZEN MESSERABATT -20% AN DEN MESSETAGEN - BIS INKL. 25.11.2019! - AUF IHRE BESTELLUNG! …UND SO FUNKTIONIERT‘S F.11 BERNHARD OTT GRÜNER VELTLINER DER OTT THE SIBLINGS WINERY B.24 ROTGIPFLER 53 890 16 9 006 Messepreis: WINKLER HERMADEN2 1 60 WELSCHRIESLING KLÖCHER STK D.3 00 21 27 sta Messepreis: 800 5 466 FAMILLE PERRIN 10060 99 CHATEAUNEUF DU PAPE2 LES SINARDS WEBSHOP 9 799 ODER sta Messepreis: B.14 72 89053 2 100616 9 8 90 10 sta Messepreis: 34 93 99 sta 42 2 100616 989053 weinco.at Kärtchen der Gewünschte Produkte Lieblingsweine suchen und in sammeln den Warenkorb legen Kärtchen beim Messerabatt durch Eingabe Bestellpoint abgeben und des Promotion-Codes gewünschte Menge und im Warenkorb sichern: Lieferdaten bekannt geben MONDOVINO19 AUFTRAGSBESTÄTIGUNG MITNEHMEN UND LIEBLINGSPRODUKTE LIEFERN LASSEN! Messe-Rabatt gültig nur auf das Messe-Sortiment für einen Einkauf pro Person, von 22.11. – 25.11.2019. Gilt nicht auf bereits getätigte Bestellun- gen und Einkäufe sowie beim Kauf von Gutscheinen, Subskriptionen und Pre-Sales. Nicht kombinierbar mit Aktionspreisen, Ikonen, Raritäten, Eventtickets, Mengenrabatt und anderen Rabatt- und Wertgutscheinen sowie Promotion-Codes. Einzulösen im angegebenen Zeitraum direkt auf der MondoVino und in jeder WEIN & CO Filiale und im WEIN & CO Webshop. Bei einer Lieferadresse außerhalb Österreichs kann es aufgrund abweichender Steuern und Abgaben zu Preisänderungen kommen. 4 B WC 22 -

Skins and the Impossibility of Youth Television

Skins and the impossibility of youth television David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays, can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. In 2007, the UK media regulator Ofcom published an extensive report entitled The Future of Children’s Television Programming. The report was partly a response to growing concerns about the threats to specialized children’s programming posed by the advent of a more commercialized and globalised media environment. However, it argued that the impact of these developments was crucially dependent upon the age group. Programming for pre-schoolers and younger children was found to be faring fairly well, although there were concerns about the range and diversity of programming, and the fate of UK domestic production in particular. Nevertheless, the impact was more significant for older children, and particularly for teenagers. The report was not optimistic about the future provision of specialist programming for these age groups, particularly in the case of factual programmes and UK- produced original drama. The problems here were partly a consequence of the changing economy of the television industry, and partly of the changing behaviour of young people themselves. As the report suggested, there has always been less specialized television provided for younger teenagers, who tend to watch what it called ‘aspirational’ programming aimed at adults. Particularly in a globalised media market, there may be little money to be made in targeting this age group specifically. -

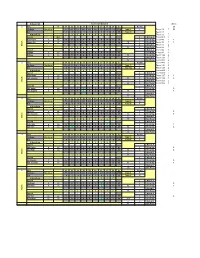

Week 6 Scorecard

5/13/2021 Scorecard (Back 9) Skins 1 Hole In 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points 13 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #1 7 Team #1 7 33 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #7 Team #7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #2 7 Team #1 -17 Net 2 Match A Team #21 2 Nick Fischer 1 38 4 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 5 39 1 Show Up Team #3 2 1 h c Deacon Jim 2 37 4 5 4 5 4 4 4 4 5 39 78 1 Show Up Team #5 7 1 t a -1 3 2 Match B Team #6 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 75 1 Net Total Team #8 7 Team #7 -1 1 1 1 1 4 Match A Team #4 5 A-Player 5 35 5 6 4 4 5 3 4 4 5 40 Show Up Team #9 4 B-Player 6 35 5 5 5 4 5 3 5 4 4 41 81 Show Up Team #12 4 -1 1 1 1 1 4 11 Match B Team #20 5 78 Net Total Team #13 4 2 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Team #15 5 Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #2 7 Team #14 5 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #21 2 Team #19 4 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #16 2 Team #2 -9 2 Match A Team #18 7 Kerry Brown 7 34 5 6 5 5 4 4 5 3 4 41 1 Show Up Team #17 6 1 h c Tom Jennings 8 34 4 5 5 4 5 3 7 3 6 42 83 1 Show Up Team #22 3 1 t a -9 1 1 15 2 Match B Team #23 2 M 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 68 1 Net Total Team #24 1 Team #21 -9 Match A Phil Hoefert 7 38 6 6 5 4 5 4 5 5 5 45 1 Show Up 1 Gary Osborne 7 34 5 7 5 3 5 4 4 4 4 41 86 1 Show Up 1 -11 14 Match B 72 Net Total 3 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Points Yardage Handicap 350 440 302 343 332 117 320 149 301 2654 Team #3 2 Par 4 5 4 4 4 3 4 3 4 35 Team #5 7 H Handicap 2 3 1 4 5 9 6 8 7 Team #3 -23 Match A Steve Hill 2 41 4 5 6 5 5 4 7 3 4 43 1 Show Up 1 h c Mike