H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Guidelines and Role Descriptions For

Book of Projects 2012 ProectsBook12ofScript&Pitch Audience Design Writer’s Room The Pixel Lab FrameWork AdaptLab 1 Book of Projects 2012 ProectsBook12ofScript&Pitch Audience Design Writer’s Room The Pixel Lab FrameWork AdaptLab TorinoFilmLab has reached its fifth edition this year, Now that we are 5 years old, I must think of and it is a pleasure to celebrate together with those what I hope we can achieve for our 10th birthday. who have supported us since the very beginning: TorinoFilmLab is on the map now, but what is most Regione Piemonte, Comune di Torino and Ministero important is that we become, more and more, a per i Beni e le Attività culturali. community of filmmakers from all around the world, sharing experiences, knowledge, successes, failures, In these years, TorinoFilmLab has grown steadily, friendships, collaborations, projects, ideas…. adding programmes, activities and partners from all TorinoFilmLab works to offer opportunities, to create over Europe and the world. What in 2008 started a space were professionals in the cinema and media with 2 training activities, a co-production market and world can - if not find all they need, at least find a production fund, now runs 6 training activities that useful directions. We have worked hard and will try still all come together (except Interchange, that finds even harder in the next years. I say we, not because I a dedicated platform at the DFC during the Dubai deserve pluralis maiestatis, but because TorinoFilmLab International Film Festival) for the TFL Meeting Event is already a community, where staff, tutors and in Torino, during the Torino Film Festival. -

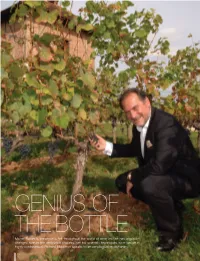

TWC009 014 Michel Rolland.Indd 70

COLLECTION WEALTH THE | xxx GENIUS OF THE BOTTLE Michel Rolland’s presence is felt throughout the world of wine and he has arguably changed forever the vinification process, yet his scientific techniques have become highly controversial. Richard Middleton speaks to an oenological revolutionary. 70 TWC009_014 Michel Rolland.indd 70 18/9/08 14:57:20 lifestyle veryone seems to agree, whether you are speaking to a fan or a critic Critics of Rolland argue this is the problem. He is, to them, an all- that, over his 35 year career, Michel Rolland has changed the face consuming global force, reducing the art and finesse of wine production to | of the multi-billion pound wine industry. With his hotly debated a mere formula. THE E WEALTH techniques for transforming dwindling vineyards into productive, and of The controversy and Rolland’s celebrity status resulted in one of the course, profitable concerns, he has positioned himself as a wine guru. But his wine world’s definitive big-screen moments, Jonathan Nossiter’s 2004 COLLECTION projects certainly pay financial dividends. And he’s stirred up a fair amount film Mondovino. In the film Nossiter explored just what made Rolland’s of controversy along the way. techniques so controversial. He contrasted converts’ adoration with the ‘I came into the wine business in 1973 and at that time everything was opinions of those who argued that producers’ are too easily won over by wrong because the 60s and 70s were only oriented to production, not ‘Parker-friendly wines (controversial wine critic Robert Parker). quality,’ Rolland says. -

Southern France Roberson Wine Tasting

ROBERSON WINE PRESENTS THE WINES OF SOUTHERN FRANCE WAW Page 53 Map 10 France Regional CORSE 7 Ajaccio N International boundary Département boundary Chief town of département VDQS Centre of VDQS AC not mapped elsewhere Centre of AC area Champagne (pp.78–81) Loire Valley (pp.118–25) Burgundy (pp.54–77) Jura and Savoie (pp.150–51) Rhône (pp.130–39) Southwest (pp.112–14) THE WINES OF Dordogne (p.115) SOUTHERN Bordeaux (pp.82–111) FRANCE Languedoc-Roussillon (pp.140–45) Provence (pp.146–48) Alsace (pp.126–29) Corsica (p.149) Other traditional vine-growing areas Proportional symbols Area of vineyard per département in thousands of hectares (no figure given if area <1000 hectares) LANGUEDOC PROVENCE 1:3,625,000 Km 0 50 100 150 Km ROUSSILLONMiles 0 50 100 Miles The Languedoc and Roussillon constitutes the world’s largest wine growing region, with a total of over 700,000 acres under vine (Provence adds another 70,000 or so) and for many years these three regions were the source of a great deal of France’s ‘wine lake’, making wine that nobody wanted to drink, let alone part with their hard earned francs for. The last decade has seen all of that change, and what was once the land of plonk is now one of the most exciting regions in the world of wine, with innovative vignerons producing both artisanal limited production cuvées and branded wines of vastly improved quality. The array of styles from this fascinating region offers wonderful diversity for the enthusiast - from dry and mineral white wines through crisp rosés to deep, structured red wines and on to unctuous sweet and fortified wines. -

Katalog 2019 22./23

Die ganze Welt des Weins im MAK MESSE KATALOG 2019 22./23. NOVEMBER FR 22.11.2019 | 15-21 UHR SA 23.11.2019 | 15-21 UHR NOTIZEN MESSERABATT -20% AN DEN MESSETAGEN - BIS INKL. 25.11.2019! - AUF IHRE BESTELLUNG! …UND SO FUNKTIONIERT‘S F.11 BERNHARD OTT GRÜNER VELTLINER DER OTT THE SIBLINGS WINERY B.24 ROTGIPFLER 53 890 16 9 006 Messepreis: WINKLER HERMADEN2 1 60 WELSCHRIESLING KLÖCHER STK D.3 00 21 27 sta Messepreis: 800 5 466 FAMILLE PERRIN 10060 99 CHATEAUNEUF DU PAPE2 LES SINARDS WEBSHOP 9 799 ODER sta Messepreis: B.14 72 89053 2 100616 9 8 90 10 sta Messepreis: 34 93 99 sta 42 2 100616 989053 weinco.at Kärtchen der Gewünschte Produkte Lieblingsweine suchen und in sammeln den Warenkorb legen Kärtchen beim Messerabatt durch Eingabe Bestellpoint abgeben und des Promotion-Codes gewünschte Menge und im Warenkorb sichern: Lieferdaten bekannt geben MONDOVINO19 AUFTRAGSBESTÄTIGUNG MITNEHMEN UND LIEBLINGSPRODUKTE LIEFERN LASSEN! Messe-Rabatt gültig nur auf das Messe-Sortiment für einen Einkauf pro Person, von 22.11. – 25.11.2019. Gilt nicht auf bereits getätigte Bestellun- gen und Einkäufe sowie beim Kauf von Gutscheinen, Subskriptionen und Pre-Sales. Nicht kombinierbar mit Aktionspreisen, Ikonen, Raritäten, Eventtickets, Mengenrabatt und anderen Rabatt- und Wertgutscheinen sowie Promotion-Codes. Einzulösen im angegebenen Zeitraum direkt auf der MondoVino und in jeder WEIN & CO Filiale und im WEIN & CO Webshop. Bei einer Lieferadresse außerhalb Österreichs kann es aufgrund abweichender Steuern und Abgaben zu Preisänderungen kommen. 4 B WC 22 -

Vincent and the End of the World

VINCENT AND THE END OF THE WORLD CONTACT INTERNATIONAL PRESS: CONTACT WORLD SALES: Beta Cinema, Dorothee Stoewahse Beta Cinema, Dirk Schuerhoff / Thorsten Ritter / Tassilo Hallbauer Mob: + 49 170 63 84 627, Office: + 49 89 67 34 69 15, Tel: + 49 89 67 34 69 828, Fax: + 49 89 67 34 69 888 [email protected] [email protected], www.betacinema.com VINCENT AND THE END OF THE WORLD DRAMA / BELGIUM – FRANCE / 2016 / RUNNING TIME - 121 MIN / FRAMES: 24 FPS / SCREEN RATIO: SCOPE 2:39 ORIGINAL TITLE: VINCENT CAST Nicole Alexandra Lamy Vincent Spencer Bogaert Marianne Barbara Sarafian Raf Geert Van Rampelberg Guillaume Frédéric Epaud Kelly Emma Reynaert Nadia Kimke Desart CREW Writer Jean-Claude Van Rijckeghem Director Christophe Van Rompaey Producer Dries Phlypo Emmanuel Giraud Aurélie Bordier Jean-Claude Van Rijckeghem Pierre Vinour Produced by A Private View Les Films de la Croisade Les Enragés Director of Photography David Williamson Set Design Hubert Pouille Editor Alain Dessauvage Production Manager Marc Dalmans Line Producer Grietje Lammertyn Sound Dirk Bombey Music Nicolas Repac 2 VINCENT AND THE END OF THE WORLD SHORT SYNOPSIS Vincent to France anyway. She will show him how beautiful life is. Marianne breaks into a panic and tries to convince Raf to take Vincent is a 17-year old ecologist who drives his family crazy off in pursuit. Raf refuses, arguing that a change of air will do with his attempts to reduce their carbon footprint. Vincent‘s Vincent a world of good. giddy French aunt Nikki takes him on a trip to France, convinced that the boy‘s obsession is related to his suffocating mother. -

LRB · Steven Shapin: Hedonistic Fruit Bombs

LRB · Steven Shapin: Hedonistic Fruit Bombs http://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n03/print/shap01_.html HOME SUBSCRIBE LOG OUT CONTACTS SEARCH LRB 3 February 2005 Steven Shapin screen layout tell a friend Hedonistic Fruit Bombs Steven Shapin Bordeaux by Robert Parker Buy this book The Wine Buyer’s Guide by Robert Parker and Pierre-Antoine Rovani Buy this book Mondovino directed by Jonathan Nossiter (2004) Sancho Panza fancied himself a wine connoisseur of rare ability. Challenged on his claim to have a ‘great natural instinct in judging wines’, he assured a sceptic that you ‘have only to let me smell one and I can tell positively its country, its kind, its flavour and soundness, the changes it will undergo and everything that appertains to a wine’. It was, he said, an innate ability, especially pronounced on his father’s side of the family, which had two of the best wine-tasters in all of La Mancha. Sancho told the sceptic a story demonstrating just how remarkable a skill this was. Some doubtful villagers gave the two of them some wine out of a cask to try, asking their opinion as to the condition, quality, goodness or badness of the wine. One of them tried it with the tip of his tongue, the other did no more than bring it to his nose. The first said the wine had a flavour of iron, the second said it had a stronger flavour of leather. The owner said the cask was clean, and that nothing had been added to the wine from which it could have got a flavour of either iron or leather. -

Bourdeaux/Burgundy

UC_Pitte (B1-G+).qxd 1/8/08 11:08 AM Page 1 CHAPTER 1 WEIGHING THE EVIDENCE The famous anecdote of the Faubourg Saint-Germain told by Brillat- Savarin, which I have used as an epigraph, reveals an educated and eclectic connoisseur who varies his wines to suit the food he eats, the weather, and his mood. Brillat-Savarin himself, another amiable judge, delighted in having been born in Belley, at the gates of the ancient cap- ital of the Gauls, a land superbly irrigated by all the fine red wines of France: “Lyons is a town of good living: its location makes it rich equally in the wines of Bordeaux and Hermitage and Burgundy.”1 He does not say that these wines are frequently mixed in the secrecy of the négociant’s warehouse, a practice that was already venerable in his time and that one hopes has now, at the beginning of the twenty-first cen- tury, finally ceased. Many poets, bacchic or other, have sung of their fondness for Bor- deaux and Burgundy. Thus André Chénier, on the eve of the Revolution: On the blessed banks of Beaune and Aï, In rich Aquitaine, and the lofty Pyrenees, From their groaning presses flow streams Of delicious wines ripened on their slopes.2 Even if Thomas Jefferson passionately loved the great wines of Bor- deaux, he also had a high regard for those of Burgundy, which we 1 Copyrighted Material UC_Pitte (B1-G+).qxd 1/8/08 11:08 AM Page 2 2/Weighing the Evidence know he thoroughly enjoyed on passing through the Côte d’Or in March 1787.3 In the early nineteenth century, the chansonnier Marc Antoine Désaugiers traveled as far without leaving home: Friends, it is in preferring The bottle to the carafe That the most ignorant man Becomes a good geographer.4 Beaune, land so highly praised, Chablis, Mâcon, Bordeaux, Grave, With what exquisite pleasure I visit you in my cellar!5 And thus, a bit later, the bard of good food and wine, Charles Monselet: It is one o’clock in the afternoon When all the fine wines meet at a feast, The fraternal hour when Lafite appears In the company of Chambertin. -

JWE2008-V3-No2-Reviews

Journal of Wine Economics, Volume 3, Issue 2, Fall 2008, Pages 205–225 Book and Film Reviews Author, Title Reviewer Alice Feiring The Battle for Wine and Love or How I Saved the World From Parkerization Stephen Chaikind Benjamin Wallace The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine Orley Ashenfelter Tyler Colman Wine Politics: How Governments, Environmentalists, Mobsters and Critics Infl uence the Wines We Drink Michael Veseth Randall Miller (director) Bottle Shock (screenplay by Jody Savin and Randall Miller) Rob Valletta Tadashi Agi (writer) and Shu Okimoto (illustrator) Kami no Shizuku: Les Gouttes de Dieu Peter Musolf Fritz Allhoff (editor) Wine & Philosophy: A Symposium on Thinking and Drinking Joshua Hall ALICE FEIRING: The Battle for Wine and Love or How I Saved the World From Parker- ization. Harcourt, Orlando, 2008, 271 pp., ISBN 978-0-15-101286-2, $23.00. After reading this book, many people may not be able to look a bottle of wine in the face the same way again. Does this matter for the enjoyment of wine? Maybe. Or maybe not. But for those doing research on the economics of wine, The Battle for Wine and Love or How I Saved the World From Parkerization by Alice Feiring provides important insights that will inform one’s perspectives about wine and the wine business. Feiring, a wine writer and reviewer, laments the growing number of wines that taste the same to her—a taste that she dislikes immensely. For Feiring, wines must exhibit fi nesse, © The American Association of Wine Economists, 2008 008_wine8_wine eeconomics_Bookconomics_Book RReviewseviews ((205205 220505 11/20/2009/20/2009 55:01:08:01:08 PPMM 206 Book Reviews a sense of place, of terroir. -

Jim's Video List 1 Filter: Minimum Score of 7 Or a Special Recommendation

11/07/20 Jim's Video List 1 Filter: Minimum score of 7 or a special recommendation. This is a non-official, pseudo-scientific list of less-than-obvious movies that I've seen and are worth your viewing time, keeping in mind that I like many different kinds of movies. All ratings are just a quick guide to relative enjoyability and socially redeeming value (if any). Also included are films of suspect social value but which left me really glad I had seen them at least once. What results is a hodge-podge of films that should keep you from taking home a real turkey. Note: Subsections like "CULT" are sorted by year. 123... '71 8 Well-crafted action thriller in which a British soldier is separated from Strause, The Brothers (2014) Action / Drama [R] his unit during a street battle in Belfast and must make his way through the labyrinth of city streets and hidden agendas of those he meets. 10 Cloverfield Lane 8 A unique bit of tense, cross-genre fun as a young woman wakes up in Trachtenberg, Dan (2016) Thriller / Horror a secure bunker, saved from World War III by a survivalist. Maybe. Or [PG-13] maybe it's from something else. Or maybe she's not safe at all. Well, damn. 10 Items Or Less 7 In this small "day in two lives" comedy-drama, an actor researching a Silberling, Brad (2006) Drama / Comedy [R] part meets a tough but dejected cashier and pushes her along a path on which she was only taking tentative steps. -

Discourse Conventions in the Construction of Wine Qualities in the Wine Market

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Diaz-Bone, Rainer Article Discourse conventions in the construction of wine qualities in the wine market economic sociology_the european electronic newsletter Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne Suggested Citation: Diaz-Bone, Rainer (2013) : Discourse conventions in the construction of wine qualities in the wine market, economic sociology_the european electronic newsletter, ISSN 1871-3351, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne, Vol. 14, Iss. 2, pp. 46-53 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156009 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Discourse Conventions in the Construction of Wine Qualities in the Wine Market 46 Discourse Conventions in the Construction of Wine Qualities in the Wine Market By Rainer DiazDiaz----Bone*Bone* investments. -

Wein-Wikipedia.Pdf

Wein – Wikipedia http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wein aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Wein (entlehnt über provinzlateinisch vino aus lat. vinum) ist ein alkoholisches Getränk aus dem vergorenen Saft von Weinbeeren. Diese Beerenfrüchte wachsen in traubenartigen Rispen an der Weinrebe. Sie stammen überwiegend von der europäischen Weinrebe Vitis vinifera, einer nicht reblausresistenten Rebenart, die deshalb auf teilresistente Unterlagen (Wurzeln) der Arten Vitis riparia, Vitis rupestris, Vitis berlandieri bzw. deren interspezifischen Kreuzungen, aufgepfropft wird. Traube eines alten Syrah- Rebstockes: Wein ist ein Die Geschichte des Weinbaus lässt sich vermutlich über fast 8000 Kulturprodukt, hergestellt aus dem Jahre zurückverfolgen. Der Wein spielte seit dem Altertum als Naturprodukt Traube. agrikulturelles Erzeugnis eine bedeutende Rolle im sozialen und rituellen Leben, insbesondere aber als transzendentes Symbol zahlreicher Mythologien und Religionen. Die im Weingenuss gesuchte Ekstase wurde dabei als etwas betrachtet, das Nähe zu einer Gottheit schaffen kann. Eine messianische Bedeutung kommt dem Wein in der jüdischen und christlichen Religion zu. In der europäischen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte stellt er einen zentralen Motiv- und Themenkomplex mit verschiedenen Bedeutungsebenen dar. Die europäische Kultur der festlichen Tafel verbindet den Wein als Teil eines gesellschaftlichen repräsentativen Rituals mit dem [1][2] festlichen Ereignis. Wo Wein kultiviert wird, sind oft einzigartige Kulturlandschaften Die häufigsten Weine sind Rot- -

SKY PINNICK (Director and Producer), Boom Varietal: the Rise of Argentine Malbec, Executive Director Kirk Ermisch

Book and Film Reviews 117 SKY PINNICK (Director and Producer), Boom Varietal: The Rise of Argentine Malbec, Executive Director Kirk Ermisch. Rage Production, Inc. and Southern Wine Group, LLC, 2011, 72 minutes. Boom Varietal, a full-length documentary about Argentina’s Malbec wine, made its debut at the Bend Film Festival in Oregon in October of 2011. Since that time it has been screened at more than twenty indie film festivals throughout the United States. The project is a joint effort of Kirk Ermisch, President of the Southern Wine Group and principal owner of Bodega Calle in Mendoza, Argentina, and Sky Pinnick, owner of Rage Productions. The film was shot on location around Mendoza, Argentina over an eight-week period of time. Malbec is a wine that we all know a little bit about. Those schooled in French wine will remember it as one of the classic Bordeaux blending grapes. It is a wine produced in a New World style, using Old World grapes, in an emerging wine country. Most restaurants list a single Malbec on their wine menu and, even given their mark-up, these wines often represent a reasonably priced accompaniment to dinner asking for a full-bodied red wine. They are generally neither too robust nor too light when trying to satisfy a mixed array of palates. Many a consumer has stocked a home bar in preparation for a party with Malbec. In brief, Malbec generally fits in a consumer’s budget and most red wine drinkers at the table or party will be pleased with the choice.