A Translocal Approach to Dialogue-Based Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributors

Contributors Andres Ajens is a Chilean poet, essayist, and translator. His latest works include /E (Das Kapital, 2015) and Bolivian Sea (Flying Island, 2015). He co-directs lntemperie Ediciones (www.intemperie. cl) and Mar con Soroche (www.intemperie.cl/soroche.htm). In English: quase ftanders, quase extramadura, translated by Erin Moure from Mas intimas mistura (La Mano Izquierda, 2008), and Poetry After the Invention ofAmerica: D on't L ight the Flower, translated by Michelle Gil-Montero (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). Mike Borkent holds a doctorate from and teaches at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on cognitive approaches to multimodal literatures, focusing on North American visual poetry and graphic narratives. He recently co-edited the volume Language and the Creative Mind (CSLI 2013) with Barbara Dancygier and Jennifer Hinnell, and has authored several articles and reviews on poetry, comics, and criticism. He was also the head developer and co-author of CanLit Guides (www. canlitguides.ca) for the journal Canadian L iterature (2011-14). Hailing from Africadia (Black Nova Scotia), George Elliott Clarke is a founder of the field of African-Canadian literature. Revered as a poet, he is currently the (4th) Poet Laureate of T oronto (2012-15). The poems appearing here are from his epic, "Canticles," due out in November 2016 from Guernica Editions. Ruth Cuthand was born in Prince Albert and grew up in various communities throughout Alberta and Saskatchewan. With her Plains Cree heritage, Cuthand's practice explores the frictions between cultures, the failures of representation, and the political uses of anger. Her mid-career retrospective exhibition, Back Talk, curated by Jen Budney from the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon, has been touring Canada since 2011. -

Ruth Cuthand CV

RUTH CUTHAND Born in 1954 in Prince Albert, SK, Canada. Lives and works in Saskatoon, SK, Canada. EDUCATION 1992 MFA, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 1983 BFA, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink, dc3 Art Projects, Edmonton, AB, Canada 2015 Don’t Drink, Don’t Breathe, Mann Art Gallery, Prince Albert, SK, Canada 2014 BACK TALK: Ruth Cuthand (works 1983-2009), Plug In ICA, Winnipeg, MB, Canada 2013 BACK TALK: Ruth Cuthand (works 1983-2009), Thunder Bay Art Gallery,Thunder Bay, ON, Canada 2012 BACK TALK: Ruth Cuthand (works 1983-2009), Confederation Art Centre, Charlottetown, PEI, Canada BACK TALK: Ruth Cuthand (works 1983-2009), Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, NS, Canada 2011 BACK TALK: Ruth Cuthand (works 1983-2009), Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 2010 Dis-Ease, Red Shift Gallery, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 1999 Indian Portraits: Late 20th Century, Wanuskewin Museum, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 1993 Location/Dislocation, Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 1992 Misuse is Abuse II, MFA Exhibition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 1990 Misuse is Abuse, Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, SK, Canada Traces of the Ghost Dance, Artists with Their Work, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, SK, Canada SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 Counter History and the Other, Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Saskatoon, SK, Canada 2015 Oh, Canada, Glenbow Museum, Illingworth Kerr Gallery, The Esker Foundation and Nickle Galleries, Calgary, AB, Canada -

The Numinous Land: Examples of Sacred Geometry and Geopiety in Formalist and Landscape Paintings of the Prairies a Thesis Submit

The Numinous Land: Examples of Sacred Geometry and Geopiety in Formalist and Landscape Paintings of the Prairies A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art and Art History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kim Ennis © Copyright Kim Ennis, April 2012. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Art and Art History University of Saskatchewan 3 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A4 Canada i Abstract Landscape painting and formalist painting, both terms taken in their broadest possible sense, have been the predominant forms of painting on the prairie, particularly in Saskatchewan, for several decades. -

2014-2015 Manitoba Arts Council Annual Report

MISSION The Manitoba Arts Council is an arm’s-length agency of the provincial government dedicated to artistic excellence. We offer a broad-based granting program for professional artists and arts organizations. We will promote, preserve, support, and advocate for the arts as essential to the quality of life of all the people of Manitoba. VISION The Manitoba Arts Council envisions a province with a creative spirit brought about by arts at the heart of community life where: • Manitobans value a range of artistic and cultural expression; • The arts are energetically promoted as an essential component of educational excellence; and • The arts landscape is characterized by province-wide participation that spans our diverse people and communities. ORGANIZATION The Manitoba Arts Council (MAC) offers a broad range of grants and services to professional artists and arts organizations in all art forms. MAC uses the peer assessment process to award most grants. Grant applications are evaluated by a group of artists and/or arts professionals currently practicing in the types of art relevant to each application. Grants are awarded based on artistic excellence. Works of artistic excellence are characterized by qualities such as vitality, originality, relevance, creativity, innovation, experimentation, and technical and professional expertise. MAC recognizes that notions of artistic excellence evolve and that decisions based on aesthetic values will vary MANITOBA ARTS COUNCIL from one peer to the next. annual report 2014 |2015 2014 -2015 COUNCIL AND STAFF MEMBERS OF COUNCIL MANDATE In accordance with the Memorandum of Understanding with the Keith Bellamy Cheryl Bear Dr. Michael Kim CHAIR, WINNIPEG PEGUIS FIRST NATION BRANDON Province, Council supports the professional arts of demonstrated or Cynthia Brenda Blaikie Crystal Kolt potential artistic excellence for individuals, groups, and organizations; Rempel Patrick WINNIPEG FLIN FLON including funding for arts training institutions, professional assessment, 1 VICE-CHAIR, STEINBACH Jan Brancewicz Dr. -

Annual Report 2020 / 2021 3 President’S Message

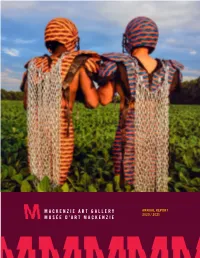

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 / 2021 3 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 5 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & CEO’S MESSAGE 7 YEAR IN REVIEW 9 EXHIBITIONS & PUBLIC PROGRAMS 21 COMMUNITY SUPPORT 23 DONORS & SPONSORS 27 ACQUISITION HIGHLIGHTS 31 MEMBERS & VOLUNTEERS 37 BOARD OF TRUSTEES & STAFF 39 SUMMARY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CORE FUNDING PROVIDED BY ADDITIONAL SUPPORT PROVIDED BY Divya Mehra, There is nothing you can possess which I cannot take away (Not Vishnu: New ways of Darsána), 2020, coffee, sand, chamois leather, leather cord, metal grommets, 2.4 lbs. Photo by Sarah Fuller. Image courtesy the artist and Georgia Scherman Projects. Collection of the MacKenzie Art Gallery. ANNUAL REPORT PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Out of an abundance of caution we cancelled several key In July, the Gallery bid farewell to Executive Director & excited by John’s forward-thinking vision, and we are fundraising events in 2020 including Holiday Baazart, CEO Anthony Keindl. I want to acknowledge his many confident that his dynamic range of curatorial experience, the Gala Art Auction, and a new in-Gallery dinner series achievements during his six-year tenure at the Gallery. sound leadership, and community mindedness will help slated to launch in early December. Although this had He was instrumental in the realization of a number of us continue to grow and inspire as we enter a new phase a significant financial impact, the Gallery continued to strategic goals including the commissioning a major public of understanding our role as cultural caretakers in this receive support from our community. We extend our artwork, Duane Linklater’s Kâkikę / Forever, stewarding territory. I’d like to thank our volunteer search committee, deepest appreciation to our members, donors, and the donation of over 1,000 Indigenous artworks through Searchlight Recruiters, and members of the Board for corporate sponsors for their ongoing generosity. -

Proquest Dissertations

Mapping the Post-Colonial Landscape Project: A Critical Analysis Michael Frederick Rattray A Thesis In The Department Of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2008 © Michael Frederick Rattray, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45711-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45711-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

UAAC-AAUC-2019-Programme-Long

2019 Conference of the Universities Art Room AssociationDufferin of Canada Back to schedule Congrès 2019 de l’Association d’art des universités du Canada October 25–27 octobre 2019 Hilton Quebec 1 Message du président L’intérêt grandissant que suscite le congrès de l’AAUC fait en sorte que nous devons nous adapter à la croissance tout en préservant le caractère informel qui, au fil de plusieurs décennies, s’est avéré adaptable et productif. Cette situation enviable explique que le congrès de cette année se déroule dans un centre de congrès, un format qui sera de plus en plus important à l’avenir. Je suis heureux de terminer mon mandat de président lors de cet événement remarquable et dans ce cadre magnifique. Je tiens à remercier les organisateurs Ersy Contogouris, Erin Silver et Maxime Coulombe, et je suis ravi de voir le nouveau numéro de RACAR, qu’Ersy a codirigé avec Mélanie Boucher, et qui porte sur les tableaux vivants. Je remercie également Fran Pauzé, l’administratrice de l’AAUC, pour son travail au soutien du congrès de cette année et pour m’avoir aidé à rester sur la bonne voie pendant mon mandat au CA de l’AAUC, d’abord comme trésorier, puis comme président. Les compétences financières de Fran — un modèle d’efficacité et de clarté, je le dis sou- vent — expliquent en grande partie le succès durable de l’Association. Je me sens privilégié d’avoir été au service de ma communauté professionnelle de cette manière et j’ai hâte de participer de façons différentes au cours des années à venir, en commençant par le congrès de Vancouver en 2020. -

Eskimo Sculpture & Prints

1. Possibly 1956 Tarascan Art of Ancient Mexico - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Publication: Tarascan Art of Ancient Mexico Clare Herzog The Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1956, 8pp. 2. 15 – 30 October 1961 Eskimo Sculpture & Prints - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:[Glenbow Foundation/WCAC] 3. 22 June – 27 July 1973 Eskimo Prints and Sculpture - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:A Community Programme Exhibition Circulation: Publication:Eskimo Prints and Sculpture Paul H. Fudge Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1973, 12 p. 4. 2 – 30 July 1974 The Eskimo Art Collection of the TD Bank - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:[Toronto Dominion Bank] Circulation: Publication:The Eskimo Art Collection of the Toronto-Dominion Bank Paul Duval Toronto Dominion Bank, 1974, 48 pp. 5. 19 September – 13 October 1975 Saskatchewan Native Painters of the Past - Organized by the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:A SASKARTIST Series Exhibition/ A Prairie Artist Series Exhibition Developed by Jack Severson, Curatorial Assistant Publication:Saskatchewan Native Artists of the Past no author Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1975, 4 p. ISBN: n\a 6. 17 May – 29 June 1975 The Legacy: Contemporary British Columbia Indian Art - Organized by the British Columbia Provincial Museums Note: [B.C. Provincial Museum] 7. 12 December – 18 January 1975 100 Years of Saskatchewan Indian Art 1830 – 1930 - Organized by the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:Community Programme Exhibition Circulation: Publication:100 Years of Saskatchewan Indian Art 1830 – 1930 Bob Boyer Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1975, two books 12 p. and one book 16 p. ISBN: 8. 1 June – 9 August 1976 Eskimo Prints and Sculptures - Organized by the Community Programme of the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery 9. -

Curriculum Vitae Lethbridge, AB (587) 220-5756 [email protected] | Populust.Ca

Megan Morman - Curriculum Vitae Lethbridge, AB (587) 220-5756 [email protected] | populust.ca Solo Exhibitions Assume the Position (thesis exhibition), Penny Building Gallery, Lethbridge, AB July 2016 Now You See It, Manning Hall commission, Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, AB Aug 2013-Feb 2014 Art Party, Stride Gallery, Calgary, AB Jan-Feb 2014 Art Party & Super Bingo, Galerie Sans Nom, Moncton, NB Sep-Nov 2013 Art Party, Latitude 53, Edmonton, AB Jul-Aug 2013 Wordgames with Friends, ARTSPACE Artist Run Centre, Peterborough, ON Jun-Aug 2013 Cat Party, Parlour windowspace, Lethbridge, AB Feb-Mar 2013 Art Party, Artists by Artists show, mentor Ruth Cuthand, Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, SK Sep 2012-Jan 2013 Friends of Friends, Neutral Ground Artist Run Centre, Regina, SK Apr-May 2009 Friends of Friends, Sushiro, Saskatoon, SK Aug-Sep 2007 Public Projects and Festivals “Downtown Lethbridge”, permanent public work commissioned by the SAAG, Lethbridge, AB Oct 2014 Ottawa Super Bingo, Westfest, hosted by Gallery 101, Ottawa, ON Jun 2013 Cooler, Mountain Standard Time Performative Art Festival, Calgary, AB Oct 2012 Cooler, Visualeyez Festival of Performance Art, Latitude 53 Gallery, Edmonton, AB Sep 2009 Calgary Super Bingo, Artcity Public Art Festival, Calgary, AB Sep 2008 Overlook, temp. installation commissioned by Riversdale Business Improvement District, Saskatoon Sep 2007 Selected Group Exhibitions & Performances Broken Telephone curated by Emily McKibbon, MacLaren Art Centre, Barrie Fall 2019 Scutelliphily curated by Zoe Schneider, SK Craft Council Affinity Gallery, Saskatoon Apr-May 2017 Best of the Cabinets of Queeriosities curated by Leila Armstrong, The Works Festival, Edmonton Jun-Jul 2016 Then & Now, curated by Jessica Fisher & Courteny Green, Southern Alberta Art Gallery May-June 2016 Way In, Snelgrove Gallery, Saskatoon & Way Out, Penny Building Gallery, Lethbridge Jan & Feb 2016 Friends of Friends touring with Hi-Fibre Content curated by Zoe Schneider, Org. -

Tanya Harnett RCA MFA Suite 1606, 9717- 111 Street Curriculum Vitae Edmonton, AB, T5K 2M6 Email: [email protected]

Tanya Harnett RCA MFA Suite 1606, 9717- 111 Street Curriculum Vitae Edmonton, AB, T5K 2M6 email: [email protected] Born: 1970 Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. Nakota, Carry The Kettle band member. Education: 1999- 2001 University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. Master of Fine Art in Drawing 1992- 1995 University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. Bachelor of Fine Art in Painting and Printmaking. 1990- 1992 Grant MacEwan Community College, Edmonton, Alberta. Fine Art Diploma. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, Society of Northern Alberta Print-artists, Edmonton, Alberta. 2016 Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, Society of Northern Alberta Print-artists, Edmonton, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, Sod Busters Museum, Strome, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, Spruce Grove Public Library, Spruce Grove, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, Evergreen Elementary, Drayton Valley, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, Highlands Schools, Edmonton, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, Fox Creek Municipal Library, Fox Creek, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, Millerville Library 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibit ion, Belvedere-parkway School, Calgary, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, TREX touring exhibition, James Fowler High School, Calgary, Alberta. 2016 Lebret Residential Petroglyphs, -

Cultivating The

SASKATCHEWAN ARTS BOARD 2016-2017 ANNUAL REPORT Cultivating the ARTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal 2 Message from the Chair 3 Message from the Chief Executive Officer 4 Board & Staff 5 Stories 6 Permanent Collection: New Acquisitions 35 Permanent Collection: Works on Loan 38 In Memory 40 Strategic Planning 41 Grants & Funding 42 Jurors, Assessors & Advisors 47 Management Responsibility for Financial Information 50 Auditor's Report 51 Financial Statements 52 Notes to the Financial Statements 55 MISSION: The Saskatchewan Arts Board recognizes, encourages and supports the arts to enrich community well-being, creativity, diversity and artistic prosperity. VISION: A creative society where the arts and artistic expression play a dynamic role and are accessible to everyone in Saskatchewan. VALUES: Excellence: We support artists, organizations and communities striving for excellence in the arts. Diversity: We are committed to supporting artists and arts activities that are reflective of the diversity of Saskatchewan. Adaptability: We support artists and arts organizations as they pursue new and innovative practices. Accountability: Our policies and processes are transparent and reflect a commitment to effective stewardship of the public trust we hold. Leadership: We strive to lead through consultation, collaboration, responsiveness and advocacy. Cover: Laura St. Pierre Fruits and Flowers of the Spectral Garden (Avalon) (detail), 2014 archival inkjet on somerset velvet paper Photo courtesy of the artist See page 48 for full image. 2 SASKATCHEWAN ARTS BOARD 2016-2017 ANNUAL REPORT Artists Speak… “Artistic expression is the paint on the canvas that is our province. It takes something otherwise functional and makes it not only liveable, but lovable. -

2020 AGA Annual Report

2020 Report to the Community Contents 4 Message from the Chair of the Board of Directors 8 Message from the Executive Director 12 Collection Acquisitions 16 Singhmar Centre for Art Education 20 Exhibitions and Related Programming 26 TREX 27 Programming and Engagement 32 Membership 34 Retail Services 36 Donors and Patrons 36 Sponsors 37 Staff Listing 38 Board of Directors 38 Volunteers 39 Revenues and Expenses Mindy Yan Miller, seeing and not seeing, 2019. Hair-on-hide cowhides, acrylic slats, oiled plywood, portable metal folding sawhorses. From the exhibtion borderLINE: 2020 Biennial of Contemporary Art. Courtesy the Artist. Photo: Art Gallery of Alberta. FRONT COVER: From the opening party for Nests for the End of the World, Art Gallery of Alberta, January 2020. Photo: Leroy Schulz Report to the Community 3 4 Report to the Community Message from the Chair of the Board of Directors This past year has been a year of many “firsts.” For the first time since our opening, 98 years ago, we needed to close the AGA to the public. While our mission is to be the creative hub of Alberta, offering dynamic exhibitions, programs and a wide range of on-site educational activities, the safety of our staff and visitors required two temporary closures of our building. The Board and management worked closely with the City, the Province and other arts organizations to ensure that our re-opening in early June was done with the strictest protocols in place, providing a safe experience for all attendees, including special viewing times for vulnerable populations and free admission for first responders, healthcare workers and artists.