1 Stand Watie Stand Watie Is the Only Native American to Attain A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Free State of Winston"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston" Susan Neelly Deily-Swearingen University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Deily-Swearingen, Susan Neelly, "Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2444. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2444 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REBEL REBELS: RACE, RESISTANCE, AND REMEMBRANCE IN THE FREE STATE OF WINSTON BY SUSAN NEELLY DEILY-SWEARINGEN B.A., Brandeis University M.A., Brown University M.A., University of New Hampshire DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History May 2019 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in History by: Dissertation Director, J. William Harris, Professor of History Jason Sokol, Professor of History Cynthia Van Zandt, Associate Professor of History and History Graduate Program Director Gregory McMahon, Professor of Classics Victoria E. Bynum, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History, Texas State University, San Marcos On April 18, 2019 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Trailword.Pdf

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. _X___ New Submission ____ Amended Submission ======================================================================================================= A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ======================================================================================================= Historic and Historical Archaeological Resources of the Cherokee Trail of Tears ======================================================================================================= B. Associated Historic Contexts ======================================================================================================= (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) See Continuation Sheet ======================================================================================================= C. Form Prepared by ======================================================================================================= -

Walking with Jesus Team Name and Pool Your Miles to Reach Your Goal

A photo taken in 1903 of Walking Log Elizabeth “Betsy” Brown Stephens, age 82, a Cherokee who walked Are you walking with a team? Come up with a the Trail of Tears. Walking with Jesus team name and pool your miles to reach your goal. When you’ve completed your “walk” come to the Learn... table at Coffee Hour and receive your prize. 1838 -1839 Can you do all four walks? Why is this called the Trail of Tears? Trail of Tears Date Distance Where Why were the Cherokee forced to leave their homes? Where did they go? How long did it take for them to get there? Who was the President of the United States at this time? In the summer of 1838, U.S. troops arrested approx. 1,000 Cherokees, marched them to Fort Hembree in North Carolina, then on to deportation camps in Tennessee. ... and Ponder 2200 Miles What would it feel like to suddenly have to leave your home without taking anything with you? Take Flat Jesus with you, take photos of Have you or someone you know moved to a brand He has told you, O mortal, what is good; your adventures, and send them to new place? [email protected]! and what does the Lord require of you but Posting your pics on Facebook or What was hard about that? to do justice, and to love kindness, and to Instagram? Tag First Pres by adding Why was the relocation wrong? walk humbly with your God? @FirstPresA2 #FlatJesus. Micah 6:8 “The Trail of Tears,” was painted in 1942 by Robert Lindneux 1838-1839 Trail of Tears to commemorate the suffering of the Cherokee people. -

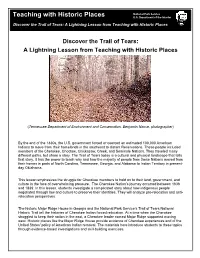

Trail of Tears: a Lightning Lesson from Teaching with Historic Places

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Discover the Trail of Tears: A Lightning Lesson from Teaching with Historic Places Discover the Trail of Tears: A Lightning Lesson from Teaching with Historic Places (Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Benjamin Nance, photographer) By the end of the 1830s, the U.S. government forced or coerced an estimated 100,000 American Indians to move from their homelands in the southeast to distant Reservations. These people included members of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations. They traveled many different paths, but share a story. The Trail of Tears today is a cultural and physical landscape that tells that story. It has the power to teach why and how the majority of people from these Nations moved from their homes in parts of North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama to Indian Territory in present- day Oklahoma. This lesson emphasizes the struggle for Cherokee members to hold on to their land, government, and culture in the face of overwhelming pressure. The Cherokee Nation’s journey occurred between 1838 and 1839. In this lesson, students investigate a complicated story about how indigenous people negotiated through law and culture to preserve their identities. They will analyze pro-relocation and anti- relocation perspectives. The historic Major Ridge House in Georgia and the National Park Service’s Trail of Tears National Historic Trail tell the histories of Cherokee Indian forced relocation. At a time when the Cherokee struggled to keep their nation in the east, a Cherokee leader named Major Ridge supported moving west. -

These Hills, This Trail: Cherokee Outdoor Historical Drama and The

THESE HILLS, THIS TRAIL: CHEROKEE OUTDOOR HISTORICAL DRAMA AND THE POWER OF CHANGE/CHANGE OF POWER by CHARLES ADRON FARRIS III (Under the Direction of Marla Carlson and Jace Weaver) ABSTRACT This dissertation compares the historical development of the Cherokee Historical Association’s (CHA) Unto These Hills (1950) in Cherokee, North Carolina, and the Cherokee Heritage Center’s (CHC) The Trail of Tears (1968) in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears were originally commissioned to commemorate the survivability of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and the Cherokee Nation (CN) in light of nineteenth- century Euramerican acts of deracination and transculturation. Kermit Hunter, a white southern American playwright, wrote both dramas to attract tourists to the locations of two of America’s greatest events. Hunter’s scripts are littered, however, with misleading historical narratives that tend to indulge Euramerican jingoistic sympathies rather than commemorate the Cherokees’ survivability. It wasn’t until 2006/1995 that the CHA in North Carolina and the CHC in Oklahoma proactively shelved Hunter’s dramas, replacing them with historically “accurate” and culturally sensitive versions. Since the initial shelving of Hunter’s scripts, Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears have undergone substantial changes, almost on a yearly basis. Artists have worked to correct the romanticized notions of Cherokee-Euramerican history in the dramas, replacing problematic information with more accurate and culturally specific material. Such modification has been and continues to be a tricky endeavor: the process of improvement has triggered mixed reviews from touristic audiences and from within Cherokee communities themselves. -

A Christian Nation: How Christianity United the People of the Cherokee Nation

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2015 A Christian Nation: How Christianity united the people of the Cherokee Nation Mary Brown CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/372 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Christian Nation: How Christianity united the people of the Cherokee Nation. There is not today and never has been a civilized Indian community on the continent which has not been largely made so by the immediate labors of Christian missionaries.1 -Nineteenth century Cherokee Citizen Mary Brown Advisor: Dr. Richard Boles May 7, 2015 “Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of the City University of New York.” 1Timothy Hill, Cherokee Advocate, “Brief Sketch of the Mission History of the Cherokees,” (Tahlequah, OK) April 18, 1864. Table of Contents Thesis: The leaders of the Cherokee Nation during the nineteenth century were not only “Christian”, but they also used Christianity to heavily influence their nationalist movements during the 19th century. Ultimately, through laws and tenets a “Christian nation” was formed. Introduction: Nationalism and the roots Factionalism . Define Cherokee nationalism—citizenship/blood quantum/physical location. The historiography of factionalism and its primary roots. Body: “A Christian Nation”: How Christianity shaped a nation . Christianity and the two mission organizations. -

Newsletter of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Partnership • Spring 2018

Newsletter of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Partnership • Spring 2018 – Number 29 Leadership from the Cherokee Nation and the National Trail of Tears Association Sign Memorandum of Understanding Tahlequah, OK Principal Chief Bill John Baker expressed Nation’s Historic Preservation Officer appreciation for the work of the Elizabeth Toombs, whereby the Tribe Association and the dedication of its will be kept apprised of upcoming members who volunteer their time and events and activities happening on talent. or around the routes. The Memo encourages TOTA to engage with The agreement establishes a line for govt. and private entities and routine communications between to be an information source on the Trail of Tears Association and the matters pertaining to Trial resource CHEROKEE NATION PRINCIPAL CHIEF BILL JOHN Cherokee Nation through the Cherokee conservation and protection. BAKER AND THE TRAIL OF TEARS PRESIDENT JACK D. BAKER SIGN A MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING FORMALIZING THE CONTINUED PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN THE TRAIL OF TEARS ASSOCIATION AND THE CHEROKEE NATION TO PROTECT AND PRESERVE THE ROUTES AS WELL AS EDUCATING THE PUBLIC ABOUT THE HISTORY ASSOCIATED WITH THE TRAIL OF TEARS. Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Bill John Baker and Trail of Tears Association President Jack D. Baker, signed a Memorandum of Understanding on March 1st, continuing a long-time partnership between the association and the tribe. Aaron Mahr, Supt. of the National Trails Intermountain Region, the National Park Service office which oversees the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail said “The Trails Of Tears Association is our primary non-profit volunteer organization on the national historic trail, and the partnership the PICTURED ABOVE: (SEATED FROM L TO R) S. -

ROSS and WATIE: the RELATIONSHIP and INFLUENCE of CHEROKEE CHIEFS, from REMOVAL to the CIVIL WAR Erik Ferguson

26 ROSS AND WATIE: THE RELATIONSHIP AND INFLUENCE OF CHEROKEE CHIEFS, FROM REMOVAL TO THE CIVIL WAR Erik Ferguson John Ross and Stand Watie were chiefs and leaders of the Cherokee people through a large part of the nineteenth century. Politically they differed in thought and action. Even though they maintained different political understanding, they both believed in the unity of the Cherokee Nation. Through their lives, their differences shaped each other and their nation. Their actions had major influences on one another. What started as a political divide became a personal grudge over decades. The decisions they made for themselves and the Cherokee people had great effect on each other. Their political movements were not only based on the Cherokee people, but on how the other would react. This relationship began in the early 19th century and went through the Civil War. They were a part of treaties, assassinations, peace, and war. They influenced and changed their nation, and influenced and changed each other. In order to understand the relationship of Ross and Watie, one must understand the primitive law of the Cherokee. An outside observer may not see any structure or order to early Cherokee society, but even though their laws were not written down they were still understood by their people. Social harmony and popular consensus was the cornerstone of Cherokee order. Consensus did not have to come from vote, but often came when the opposition gave up their side or left the council. It was also custom for young men to defer to their elders, whose opinions held more weight than their young counterparts. -

The Judicial History of the Cherokee Nation from 1721 to 1835

This dissertation has been 64—13,325 microfilmed exactly as received DICKSON, John L ois, 1918- THE JUDICIAL HISTORY OF THE CHEROKEE NATION FROM 1721 TO 1835. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1964 History, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE JUDICIAL HISTORY OF THE CHEROKEE NATION FROM 1721 TO 1835 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JOHN LOIS DICKSON Norman, Oklahoma 1964 THE JUDICIAL HISTORY OF THE CHEROKEE NATION FROM 1721 TO 1835 APPROVED BY A M ^ rIfaA:. IÀ j ^CV ' “ DISSERTATION (XMHTTEE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Grateful acknowledgement is extended to the follow ing persons vdio have helped me both directly and indirectly: Miss Gabrille W. Jones and Mrs. H. H. Keene of the Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Ttilsa, Okla homa; Miss Sue Thorton and Mrs. Reba Cox of Northeastern State College, Tahlequah, Oklahoma; Miss Louise Cook, Mrs. Dorothy Williams, Mrs. Relia Looney, and Mrs. Mar on B. At kins of the Oklahoma Historical Society; and to Mrs. Alice Timmons of the Phillips Collection as well as the entire staff of the University of Oklahoma Library. Particularly, I would like to thank Mr. Raymond Pillar of Southeastern State College Library for his help in making materials avail able to me. I also wish to thank all members of my doctoral com mittee at the University of Oklahoma and also President Allen £• Shearer, Dr. James Morrison, and Dr. Don Brown of South eastern State College. -

The Treaty of New Echota and General Winfield Scott

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2003 Cherokee Indian Removal: The rT eaty of New Echota and General Winfield cott.S Ovid Andrew McMillion East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation McMillion, Ovid Andrew, "Cherokee Indian Removal: The rT eaty of New Echota and General Winfield Scott." (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 778. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/778 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cherokee Indian Removal: The Treaty of New Echota and General Winfield Scott _________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters in Arts _________________________ by Ovid Andrew McMillion May 2003 _________________________ Dr. Dale Royalty, Chair Dr. Colin Baxter Dr. Dale Schmitt Keywords: Cherokee Indians, Winfield Scott, Treaty of New Echota, John Ross ABSTRACT The Treaty of New Echota and General Winfield Scott by Ovid Andrew McMillion The Treaty of New Echota was signed by a small group of Cherokee Indians and provided for the removal of the Cherokees from their lands in the southeastern United States. This treaty was secured by dishonest means and, despite the efforts of Chief John Ross to prevent the removal of the Cherokees from their homeland to west of the Mississippi River, the terms of the treaty were executed. -

Omo Shticeiii

OMO SHTICEIII 1IOIOI1SH II IV ACKHOV/LEDGME1TTS I am indebted to Hon. W. V/. Hastings, Member of the United States Congress for books from the Library of Con gress and books from his private -library; to Dr. 1!. P. Ham- moiid, president of northeastern State Teachers College, Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for assistance in securing material through the college library; to Dr. Frans Olbrechts, Bel gium, to Llr. Lev/is Spence, Edinburgh, Scotland, and Miss Eula E. Fullerton (a student of Cherokee history and life, manners and customs) professor of history, northeastern State Teachers College,, Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for their helpful sug gestions; to the Hewberry Library, Chicago, Illinois, for photostats of that part of the John Howard Payne Manuscript dealing v/ith the religious festivals of the Cherokees; to I.Iiss Lucy Ann Babcock, Librarian, northeastern State Teachers College, Tahlequah, Oklahoma, in calling ray attention to cer tain books; to Ross Daniels, government official among the Indians, for negatives from which some of the Illustrations are made; to b. J. Seymour, Camden, Arkansas, and Miss A- licia Hagar, Joplin, Missouri, for proof reading; and'to Miss Josephine C. Evans, my secretary, for assistance"in prepar ing the bibliography and the index. YI COUTBHIS CHAPTER PAGE I1TTRODUCTIC1T. ............................... I. A GEHERAL ST^TEMEIIT COHCER17ILTG THE AMERICA1I M* ............................. .... 1 The Singular Characteristics of the A- rnerican Indians ....................... 2 The Culture of the American Indians.... 11 The Warfare of the American Indians.... 20 The Religion of the American Indians... 26 The Ethics of the American Indians..... 32 II. A GEliERAL STATEMENT C01TCERHI1IG THE CKSROKEE niDLiilTS ................................... 39 The Cherokee Dialects ................. -

Major Ridge, Leader of the Treaty Party Among the Cherokees, Spent The

Historic Origins of the Mount Tabor Indian Community of Rusk County, Texas Patrick Pynes Northern Arizona University Act One: The Assassination of Major Ridge On June 21, 1839, Major Ridge, leader of the Cherokee Treaty Party, stopped to spend the night in the home of his friend, Ambrose Harnage. A white man, Harnage and his Cherokee family lived in a community called Illinois Township, Arkansas. Nancy Sanders, Harnage’s Cherokee wife, died in Illinois Township in 1834, not long after the family moved there from the Cherokee Nation in the east. Illinois Township was located right on the border between Arkansas and the new Cherokee Nation in the west. Ride one mile west, and you were in Going Snake District. Among the families living in Illinois Township in 1839 were some of my own blood relations: Nancy Gentry, her husband James Little, and their extended family. Nancy Gentry was the sister of my fifth maternal grandfather, William Gentry. Today, several families who descend from the Gentrys tell stories about their ancestors’ Cherokee roots. On June 21, 1839, Nancy Gentry’s family was living nine doors down from Ambrose Harnage. Peering deep into the well of time, sometimes hearing faint voices, I wonder what Major Ridge and his friend discussed the next morning at breakfast, as Harnage’s distinguished guest prepared to resume his journey. Perhaps they told stories about Andrew Sanders, Harnage’s brother-in-law. Sanders had accompanied The Ridge during their successful assassination mission at Hiwassee on August 9, 1807, when, together with two other men, they killed Double-head, the infamous Cherokee leader and businessman accused of selling Cherokee lands and taking bribes from federal agents.