Four Problem Stints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Migratory Shorebird Guild

Migratory Shorebird Guild Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Sanderling Calidris alba Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Red Knot Calidris canutus Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola Marbled Godwit Limosa fedoa American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis Wimbrel Numenius phaeopus White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago gallinago delicata Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularia American Avocet Recurvirostra Americana Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla Short-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus griseus Western Sandpiper Calidris mauri Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus Dunlin Calidris alpina Contributors: Felicia Sanders and Thomas M. Murphy DESCRIPTION Photograph by SC DNR Taxonomy and Basic Description The migratory shorebird guild is composed of birds in the Charadrii suborder. Migrants in South Carolina represent three families: Scolopacidae (sandpipers), Charadriidae (plovers) and Recurvirostridae (avocets). Sandpipers are the most diverse family of shorebirds. Their tactile foraging strategy encompasses probing in soft mud or sand for invertebrates. Plovers are medium size birds, with relatively short, thick bills and employ a distinctive foraging strategy. They stand, looking for prey and then run to feed on detected invertebrates. Avocets are large shorebirds with long recurved bills and partial webbing between the toes. They feed employing both tactile and visual methods. Shorebirds are characterized by long legs for wading and wings designed for quick flight and transcontinental migrations. Migrations can span continents; for example, red knots migrate from the Canadian arctic to the southern tip of South America. -

The Occurrence and Identification of Red-Necked Stint in British Columbia Rick Toochin (Revised: December 3, 2013)

The Occurrence and Identification of Red-necked Stint in British Columbia Rick Toochin (Revised: December 3, 2013) Introduction The first confirmed report of a Red-necked Stint (Calidris ruficollis) in British Columbia was an adult in full breeding plumage found on June 24, 1978 at Iona Island (see Table 1, confirmed records item 1). Recently another older sighting has been uncovered that fits the timing of occurrence for this species in BC and may be valid (see Table 2, hypothetical records item 1). Since the first initial sightings in the late 1970s, there has been a slow but steady increase in observations of this beautiful Asian shorebird in British Columbia and, indeed, across the whole of North America. With an increase in both observer coverage and the knowledge of observers, this species is now known to be of regular, and probably annual, occurrence during fall migration in coastal British Columbia. Additionally, this species is now recorded occasionally during spring migration, indicating that at least a few individuals may be successfully wintering farther south in the western hemisphere. Identification of this species is straightforward when presented with a full breeding- plumaged adult, but identification of birds in juvenile and faded breeding plumage can be very complicated due to the close similarities to other small Calidris shorebirds. This paper describes the distribution and occurrence of the species in B.C., and also examines the similarities of all plumages of Red-necked Stint to species with which it might be confused, most notably Little Stint (C. minuta), Semipalmated Sandpiper (C. pusilla), and Western Sandpiper (C. -

Peeps and Related Sandpipers Peeps Are a Group of Diminutive Sandpipers That Are Notoriously Hard to Tell Apart

Peeps and Related Sandpipers Peeps are a group of diminutive sandpipers that are notoriously hard to tell apart. They belong to a subfamily of subarctic and arctic nesting sandpipers known as the Calidridinae (in the sandpiper family, Scolopacidae). During their migrations, when most residents of North America have the opportunity to watch them, mixed flocks of calidridine sandpipers scurry about on mudflats, feeding at the edge of the retreating tide, or swarm aloft, twisting and turning like a dense school of fish. These traits, in a group of birds that look so much alike to start with, give bird watchers nightmares. Fortunately for Alaskans and visitors to our state, Alaska is an excellent location to view and identify calidridine sandpipers. The early summer breeding season is the easiest time of the year to distinguish the various species, not only because they are in breeding plumage and are more approachable than at other times of the year, but also because each species performs a characteristic courtship display with unique vocalizations. For the avid birder, Alaska has the additional attraction of being one of the best places in North America to view exotic Eurasian species. General description: Three peeps are abundant summer residents and breeders in Alaska—the least, semipalmated, and western sandpipers (Calidris minutilla, C. pusilla, and C. mauri) [all lists in order by size]. Another four species from Eurasia may also be seen—the little, rufous-necked, Temminck's, and long-toed stints (“stint” is the British equivalent for peep) (C. minuta, C. ruficollis, C. temminckii, C. subminuta). These seven species range from 5 to 6½ inches (15-17 cm) in length, and weigh from 2/3 to 1½ ounces (17-33 g). -

Seven Deadly Stints and Their Friends an Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 1 Jon L

Seven Deadly Stints and their Friends An Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 1 Jon L. Dunn Larry Sansone photos 13 October 2020 Los Angeles Birders Genus Calidris – Composed of 23 species the largest genus within the large family (94 species worldwide, 66 in North America) of Scolopacidae (Sandpipers). – All 23 species in the genus Calidris have been found in North America, 19 of which have occurred in California. – Only Great Knot, Broad-billed Sandpiper, Temminck’s Stint, and Spoon-billed Sandpiper have not been recorded in the state, and as for Great Knot, well half of one turned up! Genus Calidris – The genus was described by Marrem in 1804 (type by tautonymy, Red Knot, 1758 Linnaeus). – Until 1934, the genus was composed only of the Red Knot and Great Knot. – This genus is composed of small to moderate sized sandpipers and use a variety of foraging styles from probing in water to picking at the shore’s edge, or even away from water on mud or the vegetated border of the mud. – As within so many families or large genre behavior offers important clues to species identification. Genus Calidris – Most, but not all, species migrate south in their alternate (breeding) or juvenal plumage, molting largely once they reach their more southerly wintering grounds. – Most species nest in the arctic, some farther north than others. Some species breed primarily in Eurasia, some in North America. Some are Holarctic. – The majority of species are monotypic (no additional recognized subspecies). Genus Calidris – In learning these species one -

Calidris Pusilla Class

Calidris pusilla Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Family: Scolopacidae Genus: Calidris. Distribution A highly migratory species, after breeding in the Arctic regions Calidris pusilla breeds in the of North America these sandpipers begin to travel southwards Arctic and subarctic from in July. Birds that did not breed start out first followed quickly far-eastern Siberia, east by adult females and then males that did breed and are leaving across Alaska and northern their young. These juveniles remain a little longer. Some travel Canada to Baffin Island and with late adult migrants. There is a long and arduous journey Labrador. They spend the ahead especially for these young birds. Peak migration of adults Canadian winter in is late July and early August. Most western birds migrate south northern South America. through the interior of North America. Those having nested in Some western birds are the central and eastern Arctic migrate south non-stop until they found along the Pacific reach southern James Bay, the St. Lawrence estuary, and the Bay coast of Central America. of Fundy in Canada. This is a stop over stage for rest and Smaller numbers spend this recuperation before continuing south. The spring return season in the Caribbean. migration is towards the Atlantic then continues northward. Habitat While breeding, the semipalmated sandpiper builds its nest While in the north during amongst dry shrubby areas in upland tundra near small ponds, the early summer months lakes and streams. Ideal foraging habitat includes pools close to they occupy areas of wet lakes and rivers, shrubby river deltas, and sandy areas along the sedge or sedge- tundra. -

Binder93.Pdf

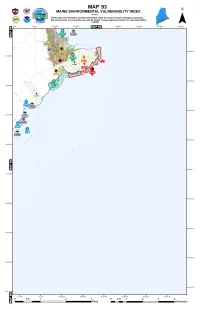

ENVIRONMENTAL SENSITIVITY MAP - 93 GEOGRAPHIC RESPONSE EVI_NO:D-33-1 PLANS (BOOMING STRATEGIES) FOR THIS MAP AREA: THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES / SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Other T or E Species Other SSC BALD EAGLE HARLEQUIN DUCK PIPING PLOVER / LEAST ROSEATE TERN SA: Sensitive Animal SA = Sensitive Animal ESSENTIAL HABITAT (BE) W INTERING HABITAT (HD) TERN ESSENTIAL HABITAT (PPLT) ESSENTIAL HABITAT (RT) SP: Sensitive Plant SP = Sensitive Plant BIRDS MONTHS PRESENT EVI NO COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME ST FEDC= COMMON U= UNCOMMON SPRING NESTING FALL WINTERING MOLTING MIGRATION MIGRATION JFM AM J JAS OND HD66 Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus T FSC C C C C U U C C Mar.- May Oct.- Dec. Nov.- Mar. SENSITIVE PLANTS / RARE ANIMALS EVI NO COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME ST FED SA78 Crowberry Blue Lycaeides idas SC SP156 Alpine Blueberry Vaccinium boreale T INVERTEBRATES MONTHS PRESENT EVI NO COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME ST FEDC= COMMON U= UNCOMMON SPAWNING EGGS PUPAE JUVENILES ADULT / FLIGHT JFM AM J JAS OND SA78 Crowberry Blue Lycaeides idas SC UUU UUU UUU UUU Jul.- Apr. May - Jun. Jun. - Jul. SHOREBIRDS (SB) SHOREBIRD SITES ON THIS MAP INCLUDE ONE OR MORE OBSERVATIONS OF THE FOLLOWING SPECIES MONTHS PRESENT COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME ST FEDC= COMMON U= UNCOMMON SPRING NESTING FALL WINTERING MOLTING MIGRATION MIGRATION JFM AM J JAS OND Red Knot Calidris canutus UUUU Jul.- Oct. Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii U U Mar.- May Aug.- Sep. Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola C C U C C C U May - Jun. Jul.- Nov. Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis UU U Aug.- Oct.