The Paper Chase How W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-22-2019 Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality Emmanuella Amoh Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the African History Commons Recommended Citation Amoh, Emmanuella, "Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1067. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1067 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KWAME NKRUMAH, HIS AFRO-AMERICAN NETWORK AND THE PURSUIT OF AN AFRICAN PERSONALITY EMMANUELLA AMOH 105 Pages This thesis explores the pursuit of a new African personality in post-colonial Ghana by President Nkrumah and his African American network. I argue that Nkrumah’s engagement with African Americans in the pursuit of an African Personality transformed diaspora relations with Africa. It also seeks to explore Black women in this transnational history. Women are not perceived to be as mobile as men in transnationalism thereby underscoring their inputs in the construction of certain historical events. But through examining the lived experiences of Shirley Graham Du Bois and to an extent Maya Angelou and Pauli Murray in Ghana, the African American woman’s role in the building of Nkrumah’s Ghana will be explored in this thesis. -

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi

Want to Start a Revolution? Gore, Dayo, Theoharis, Jeanne, Woodard, Komozi Published by NYU Press Gore, Dayo & Theoharis, Jeanne & Woodard, Komozi. Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York: NYU Press, 2009. Project MUSE., https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/10942 Access provided by The College Of Wooster (14 Jan 2019 17:31 GMT) 4 Shirley Graham Du Bois Portrait of the Black Woman Artist as a Revolutionary Gerald Horne and Margaret Stevens Shirley Graham Du Bois pulled Malcolm X aside at a party in the Chinese embassy in Accra, Ghana, in 1964, only months after hav- ing met with him at Hotel Omar Khayyam in Cairo, Egypt.1 When she spotted him at the embassy, she “immediately . guided him to a corner where they sat” and talked for “nearly an hour.” Afterward, she declared proudly, “This man is brilliant. I am taking him for my son. He must meet Kwame [Nkrumah]. They have too much in common not to meet.”2 She personally saw to it that they did. In Ghana during the 1960s, Black Nationalists, Pan-Africanists, and Marxists from around the world mingled in many of the same circles. Graham Du Bois figured prominently in this diverse—sometimes at odds—assemblage. On the personal level she informally adopted several “sons” of Pan-Africanism such as Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, and Stokely Carmichael. On the political level she was a living personification of the “motherland” in the political consciousness of a considerable num- ber of African Americans engaged in the Black Power movement. -

Freedomways Magazine, Black Leftists, and Continuities in the Freedom Movement

Bearing the Seeds of Struggle: Freedomways Magazine, Black Leftists, and Continuities in the Freedom Movement Ian Rocksborough-Smith BA, Simon Fraser University, 2003 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History O Ian Rocksborough-Smith 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Ian Rocksborough-Smith Degree: Masters of Arts Title of Thesis: Bearing the Seeds of Struggle: Freedomways Magazine, Black Leftists, and Continuities in the Freedom Movement Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. John Stubbs ProfessorIDepartment of History Dr. Karen Ferguson Senior Supervisor Associate ProfessorIDepartment of History Dr. Mark Leier Supervisor Associate ProfessorIDepartment of History Dr. David Chariandy External ExaminerISimon Fraser University Assistant ProfessorIDepartment of English Date DefendedlApproved: Z.7; E0oS SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

Riding to Freedom, the New Secession

.THE NEW SECESSION -AND HOW TO SMASH IT Riding to Freedom Herbert Aptheker * James E. Jackson 10 cent.s ~ ( 6 5/o Is- ABOUT THE AUTHORS RIDING TO FREEDOM JAMES E. JACKSON has, since the early thirties, been a prominent figure in the democratic struggles of the workers and Negro people of the South. By Herbert Aptheker He was a militant student leader and organizer of the Southern youth movement, and later an organizer among the auto workers of Michigan. He is presently the Editor of The Worker. THE MONSTROUS ASSAULTS by COW the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citi ardly gangsters and racists upon un zens' Councils and the John Bi rch HERBERT APTHEKER is the Editor of the Marxist monthly, Political armed and non-resisting young men Society, are actual conspirators in ex A ffairs, and widely known as a scholar, historian, educator and lecturer. H e and women in Alabama late in May actly the same way as the Old Se is the author of several major works including American Negro Slave Re is the culminating act of a pre-con cessionists, with their Knights of the volts, History and Reality, The Truth About H ungary and Toward Negro certed insurrectionary movement. Golden Circle, and their White Ca Freedom. His latest books, The Colonial Era and The American Revolu Earlier scenes were played out in melia Societies, maliciously plotted Florida, in Virginia, in Arkansas, the destruction of the Republic and tion: 1763-1783, are the first in a multi-volumed history of the United States. in Mississippi, in Louisiana. -

The Negro People and the Soviet Union

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1950 The Negro people and the Soviet Union Paul Robeson Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Robeson, Paul, "The Negro people and the Soviet Union" (1950). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 25. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/25 Th'e NEGRO PEOPLE .- - .- .. - MOM THE AUTHOR PAUL ROBESON is one of the foremost lead- ers of the Negro people and a concut artist of wdrenown. He has been chairman of the Cour#il on African Maim since the formation of ktvital organization 12 years aga In the summer of 1949 he returd from a four-month speaking and concert tour which took this beloved spokesman of the Negro pple to eight countries of Europe, including the Soviet Union. Whik in . Europe he participated as an honored yest in the celebration of the Pushkin centennial anniversary in MOSCOW,and in the World Peace Gmgrcss in gg:m A world-wide storm of indigoation greeted the + 3~rm-~pattacks upon him at PdcskU, N. v. Zhatnctofthispamphfetisanaddmjdefiv- 'aed by Mr. Robeson at a banquet spodby .- I& National Council of AmericanMct Friend* - ship u the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in New Yark, tm November 10, 1949, on the occasion of tht debration of the 32nd anniv~of the SaPiet Union. -

NAT TURNER's REVOLT: REBELLION and RESPONSE in SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory

NAT TURNER’S REVOLT: REBELLION AND RESPONSE IN SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory M. Thomas) ABSTRACT In 1831, Nat Turner led a revolt in Southampton County, Virginia. The revolt itself lasted little more than a day before it was suppressed by whites from the area. Many people died during the revolt, including the largest number of white casualties in any single slave revolt in the history of the United States. After the revolt was suppressed, Nat Turner himself remained at-large for more than two months. When he was captured, Nat Turner was interviewed by whites and this confession was eventually published by a local lawyer, Thomas R. Gray. Because of the number of whites killed and the remarkable nature of the Confessions, the revolt has remained the most prominent revolt in American history. Despite the prominence of the revolt, no full length critical history of the revolt has been written since 1937. This dissertation presents a new history of the revolt, paying careful attention to the dynamic of the revolt itself and what the revolt suggests about authority and power in Southampton County. The revolt was a challenge to the power of the slaveholders, but the crisis that ensued revealed many other deep divisions within Southampton’s society. Rebels who challenged white authority did not win universal support from the local slaves, suggesting that disagreements within the black community existed about how they should respond to the oppression of slavery. At the same time, the crisis following the rebellion revealed divisions within white society. -

Bernard Jaffe Papers Finding Aid : Special Collections and University

Special Collections and University Archives : University Libraries Bernard Jaffe Papers 1955-2016 4 boxes (2 linear feet) Call no.: MS 906 Collection overview A New York native with a deep commitment to social justice, Bernard Jaffe was an attorney, confidant, and longtime friend of W.E.B. Du Bois and Shirley Graham Du Bois. In 1951, Jaffe joined Du Bois's defense team at a time when the civil rights leader was under indictment for failing to register as a foreign agent. Forging a close relationship through that experience, he was retained as a personal attorney, representing the Du Bois family interests after they settled abroad. Jaffe was later instrumental in placing the papers of both W.E.B. Du Bois and Shirley Graham Du Bois and served on the executive board of the W.E.B. Du Bois Foundation, set up by Shirley's son, David Graham Du Bois. This rich collection centers on the close relationship between attorney Bernard Jaffe and his friends and clients, Shirley Graham Du Bois and W.E.B. Du Bois. Although there is little correspondence from W.E.B. Du Bois himself, the collection contains an exceptional run of correspondence with Shirley, from the time of her emigration to Ghana in 1961 until her death in China in 1977 and excellent materials relating to David Graham Du Bois and the work of the W.E.B. Du Bois Foundation. See similar SCUA collections: Africa African American Antiracism Civil rights Du Bois, W.E.B. Political activism Social justice Background on Bernard Jaffe A New York native, Bernard Jaffe joined W.E.B. -

The Many Images of Maroons Throughout the American South

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 "Father Wasn't De Onlies' One Hidin' in De Woods": The Many Images of Maroons Throughout the American South Angela Alicia Williams College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Angela Alicia, ""Father Wasn't De Onlies' One Hidin' in De Woods": The Many Images of Maroons Throughout the American South" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626383. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-35sn-v135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FATHER WASN’TDE ONLIES’ ONE HIDIN’ INDE WOODS”: THE MANY IMAGES OF MAROONS THROUGHOUT THE AMERICAN SOUTH A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Angela Alicia Williams 2003 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts la Alicia Williams Approved by the Committee, December 2003 Grey Gundaker, Chair Richard Loj — \AAv-'—' Hermine Pinson For my mom. For my dad. For my family. For everyone who has helped me along my way. -

African American History and Radical Historiography

Vol. 10, Nos. 1 and 2 1997 Nature, Society, and Thought (sent to press June 18, 1998) Special Issue African American History and Radical Historiography Essays in Honor of Herbert Aptheker Edited by Herbert Shapiro African American History and Radical Historiography Essays in Honor of Herbert Aptheker Edited by Herbert Shapiro MEP Publications Minneapolis MEP Publications University of Minnesota, Physics Building 116 Church Street S.E. Minneapolis, MN 55455-0112 Copyright © 1998 by Marxist Educational Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging In Publication Data African American history and radical historiography : essays in honor of Herbert Aptheker / edited by Herbert Shapiro, 1929 p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) ISBN 0-930656-72-5 1. Afro-Americans Historiography. 2. Marxian historiography– –United States. 3. Afro-Americans Intellectual life. 4. Aptheker, Herbert, 1915 . I. Shapiro, Herbert, 1929 . E184.65.A38 1998 98-26944 973'.0496073'0072 dc21 CIP Vol. 10, Nos. 1 and 2 1997 Special Issue honoring the work of Herbert Aptheker AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND RADICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY Edited by Herbert Shapiro Part I Impact of Aptheker’s Historical Writings Essays by Mark Solomon; Julie Kailin; Sterling Stuckey; Eric Foner, Jesse Lemisch, Manning Marable; Benjamin P. Bowser; and Lloyd L. Brown Part II Aptheker’s Career and Personal Influence Essays by Staughton Lynd, Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Catherine Clinton, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn Part III History in the Radical Tradition of Herbert Aptheker Gary Y. Okihiro on colonialism and Puerto Rican and Filipino migrant labor Barbara Bush on Anglo-Saxon representation of Afro- Cuban identity, 1850–1950 Otto H. -

Slavery and the Historians*

Slavery and the Historians* by M.l. FINLEY** ... and all for nothing ! For Hecuba! What's Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba That he should weep for her? We historians sometimes "confound the ignorant" but we do not, we trust, "cleave the general ear with horrid speech, Make made the guilty and appal the free." Yet in 1975 there was published in book-form a review, nearly 200 pages long, of the two-volume work on the economics of American Negro slavery entitled Time on the Cross. 1 The review begins by saying that Time on the Cross "should be read as theater," that it is a ''profoundly flawed work;'' its closing words are, ''It really tells us nothing of importance about the beliefs and behavior of enslaved Afro-Americans;'' and the nearly 200 pages in between are peppered with comparable, and often stronger, language. Not so strong, however, as the language employed by some other reviewers: a lengthy critique in the New York Review of Books, for example, ended by asserting that the authors now have the "heavy burden" of proving that "their book merits further scholarly atten tion." The authors of Time on the Cross, Robert Fogel and Stanley Enger man, happen to be two most distinguished economic historians. It must surely be without precedent that a scholarly work by men of this eminence should have evoked a chorus that cleaved the. general ear with horrid speech. Why? What is there about the economics of American Negro slavery, which went out of existence more than a century ago, that has led to such a horrid, massive, and still continuing outburst? The answer, of course, lies not in the first half of the nineteenth century, and surely not in the economics of slavery, but in the United States today. -

Energy and Modernity in African American Literature Walter A

“Oh, Awful Power”: Energy and Modernity in African American Literature Walter A. Gordon Submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Under the Executive Committee Of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Walter A. Gordon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “Oh, Awful Power”: Energy and Modernity in African American Literature Walter A. Gordon “‘Oh, Awful Power’: Energy and Modernity in African American Literature” analyzes the social and cultural meaning of energy through an examination of African American literature from the first half of the twentieth century—the era of both King Coal and Jim Crow. Situating African Americans as both makers and subjects of the history of modern energy, I argue that black writers from this period understood energy as a material substrate which moves continually across boundaries of body, space, machine, and state. Reconsidering the surface of metaphor which has masked the significant material presence of energy in African American literature— the ubiquity of the racialized descriptor of “coal-black” skin, to take one example—I show how black writers have theorized energy as a simultaneously material, social, and cultural web, at once a medium of control and a conduit for emancipation. African American literature emphasizes how intensely energy impacts not only those who come into contact with its material instantiation as fuel—convict miners, building superintendents—but also those at something of a physical remove, through the more ambient experiences of heat, landscape, and light. By attending to a variety of experiences of energy and the nuances of their literary depiction, “‘Oh, Awful Power’” shows how twentieth-century African American literature not only anticipates some of the later insights of the field now referred to as the Energy Humanities but also illustrates some ways of rethinking the limits of that discourse on interactions between energy, labor, and modernity, especially as they relate to problems of race. -

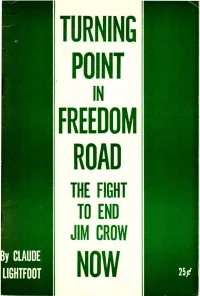

The Turning Point in Freedom Road

TURNING POINT IN FREEDOM ROAD THE FIGHT TO END JIM CROW NOW \ ., ? " • , (.f.. TURNING POINT IN FREEDOM ROAD The Fight To End Jim Crow Now By CLAUDE LIGHTFOOT NEW CENTURY PUBLISHERS: New York 1962 TO THE READER Claude Lightfoot, the author of this pamphlet is a leading Communist spokesman and an important voice among the Negro people. He was indicted, convicted, and later freed, in a federal trial for the "crime" of being a member of the Communist Party under the fascist-like provisions of the Smith Act. Mr. Lightfoot's case drew wide support as a test of the doctrine of "guilt by association." But more than that, his defense was based on the American Bill of Rights, of the right of all Americans Communists included-freely to think, speak, write and exchange their views and opinions in the public arena. He is the author of An American L ooks at R ussia: Can we Live in Peace?, Not guilty!, and numerous articles and essays which have appeared in Political Affairs and other periodicals. Published by NEW CENTURY PUBLISHERS, 832 Broadway, N. Y. 3· N. Y. October, 1962 .., 20» I'RINTED I N THE U.S.A. TURNING POINT IN FREEDOM ROAD THE FIGHT TO END JIM CROW NOW By Claude Lightfoot January, 1 g63 marks the hundredth anniversary of the issu ance of the Emancipation Proclamation; it is also nine years since the historic Supreme Court ruling on school desegregation. ·It is time for all forces dedicated to freedom's fight to make an in ventory on how matten stand in this struggle.