Chapter 13: New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand's Green Party and Foreign Troop Deployments: Views, Values and Impacts

New Zealand's Green Party and Foreign Troop Deployments: Views, Values and Impacts By Simon Beuse A Thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations Victoria University of Wellington 2010 Content List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 2 New Zealand‘s Foreign Affairs .......................................................................................... 9 2.1 Public Perceptions ....................................................................................................... 9 2.2 History ....................................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Key Relationships ...................................................................................................... 11 2.4 The Nuclear Issue ...................................................................................................... 12 2.5 South Pacific .............................................................................................................. 14 2.6 Help in Numbers: The United Nations ...................................................................... 15 2.7 Defence Reform 2000 -

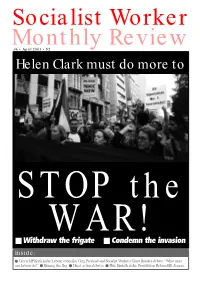

Socialist Worker Monthly Review #8 • June 2003 • $2 As Labour Bows to Bush & Business

Socialist Worker Monthly Review #8 • June 2003 • $2 As Labour bows to Bush & business... UNI STUDENTS KINLEITH MILL WORKERS PALESTINIAN HUMAN RIGHTS SUPPORTERS WEST COAST MINERS UNIVERSITY STAFF PEACE & JUSTICE CAMPAIGNERS People stand up for peace & justice Socialist Worker Monthly Review June 2003 1 What’s on of the owners have their own public, right- wing political agendas. Who owns our news Auckland media and does it mater? Presented by Bill Palestine / Israel, rally for peace Rosenberg. Support justice and peace, based on re- Trades Hall, 147 Great North Road, moval of Israeli Occupation, right of re- Grey Lynn. Tuesday, June 17, 2003 at turn for refugees, sharing Jerusalem, ces- 7:30pm. GPJA Organising Committee will sation of Jewish-only settlements in occu- be at 6:30pm, before the forum, at the pied Palestine. Unite Office, Trades Hall. Anyone willing WHO SAYS? Aotea Square (Queen St, Auckland), to help is welcome. 2pm, Saturday June 7. Organised by Pal- “There was no doubt in my mind as estine Human Rights Committee. Phone I went through the intelligence... David Wakim 520 0201. the evidencec was overwhelming Fourth of July that they had continued to develop Aceh—the New East Timor? The Fourth of July is US Independ- these programmes.” The political background, the human ence Day. This year it will be a global Colin Powell, US secretary of state. rights crisis and how New Zealand can day of protest against the US occupa- help. Speakers include Margaret Taylor tion of Afghanistan and Iraq and their “In intelligence there is one (Amnesty International), Maire military threats against Iran, Syria and unpardonable sin – cooking Leadbeater (Indonesia Human Rights Cuba. -

Form to Email

To: Bee: Subject: NZ Superannuation Fund enquiry Date: Thursday, 6 December 2012 4: 10:53 PM Attachments: Guardians Final response to Israel petition.pdf Dea . , Thank you for your email via our website. Your comments have been noted and passed on to our Chairman and CEO. I have attached a copy of the Guardians' response to the petition and FYI the Committee's report is available at http://www parliament nz/NR/rdonlyres/60EEA9A7-4218-473F-BCFF- 2347E483EBEB/244228/DBSCH $CR 5595 Petjtjon2008143ofLojsGrjffithsand38 pdf We expect to be in a position to respond more fully to your email next week. In future, please feel free to contact me directly on the details below. Best regards Catherine Etheredge Catherine Etheredge Head of Communications DDI: Mobile: Email: A Great Team Building the Best Portfolio PO Box 106 607, Auckland 1143, New Zealand Level 12, Zurich House, 21 Queen Street, Auckland 1010, New Zealand Office: +64 9 300 6980 I Fax: +64 9 300 6981 I Web: www.nzsuperfund.co.nz From: formmail@digitaistream co oz [mailto·formmail@digitaistream co oz] Sent: Thursday, 29 November 2012 2:53 p.m. To: Enquiries Subject: Query from website Form to Email Form to email received the following values Name - Company Optional Phone email from Contact Email me by Website feedback Responsible Investment Query re Responsible Investment Dear NZ Superfund, Please send this message to the Board or at least to the Chair. In September 2011,ex-MP Keith Locke presented a petition to Parliament, ■■■■■I asking for Parliament to ask the Guardians of Superfund to divest ow ve een to t at t e ommerce ommIttee as reJecte e pe 1 I0n. -

Parliamentary Scrutiny of Human Rights in New Zealand: Summary Report

Parliamentary Scrutiny of Human Rights in New Zealand: Summary Report SUMMARY REPORT Prof. Judy McGregor and Prof. Margaret Wilson AUT UNIVERSITY | UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO RESEARCH FUNDED BY THE NEW ZEALAND LAW FOUNDATION Table of Contents Parliamentary scrutiny of human rights in New Zealand: Summary report. ............................ 2 Introduction. .......................................................................................................................... 2 Policy formation ..................................................................................................................... 3 Preparation of Legislation ...................................................................................................... 5 Parliamentary Process ........................................................................................................... 8 Recommendations: .............................................................................................................. 12 Select Committee Scrutiny................................................................................................... 12 A Parliamentary Code of Conduct? ...................................................................................... 24 Parliamentary scrutiny of international human rights treaty body reports ........................ 26 New Zealand Human Rights Commission (NZHRC) ............................................................. 28 Conclusions ......................................................................................................................... -

Tenacious, Sad Account of NZ Complicity on East Timor

JOURNALISM DOWNUNDER mainstream media organisations. MATT MOLLGAARD is radio Consequently, the public sphere curriculum leader in AUT is routinely shaped by market University’s School of Communi- researchers, public relations cation Studies. He researched an practitioners and micro-managing honours thesis on East Timor. spin doctors. The reception accord- ed to Hager’s book illustrates this process. After initial controversy, Tenacious, sad Brash’s departure allowed John Key, Bill English and their advisers to rejuvenate the National brand in account of NZ a news world without political memory. complicity on References East Timor Miller, R. (2006, November 26). Brash would not have survived Hager’s Negligent Neighbour: New Zealand’s revelations, Sunday Star-Times, p. Complicity in the Invasion and Occupation A11. of Timor-Leste, by Maire Leadbeater. Nelson: Tucker, J. (2006). Hollow men, hol- Craig Potton Publishing, 2006, 280 pp. ISBN: low victory? Noted. Wellington: NZ 13: 9781877333590. Journalists Training Organisation. (Retrieved 18 April 2007): www.journalismtraining.co.nz/ HIS is an essential book for any n200703a.html Tone interested in the way that New Zealand formulates and carries out its foreign policy. It is also a stark reminder that New Zealand, a found- ing member of the United Nations, a vocal supporter of decolonisation and a country much-praised for its peacekeeping efforts all over the world has not always been willing to take a moral stance when balancing trade, security and human rights. Maire Leadbeater has produced the most detailed account so far of New Zealand’s involvement in the 204 PACIFIC JOURNALISM REVIEW 13 (1) 2007 JOURNALISM DOWNUNDER ledge of and de facto acquiescence to Indonesia’s invasion and occu- pation of East Timor. -

Parliamentary Scrutiny of Human Rights in New Zealand (Report)

PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN NEW ZEALAND: GLASS HALF FULL? Prof. Judy McGregor and Prof. Margaret Wilson AUT UNIVERSITY | UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO RESEARCH FUNDED BY THE NEW ZEALAND LAW FOUNDATION Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 2 Recent Scholarship ..................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 22 Select committee controversy ................................................................................................. 28 Rights-infringing legislation. .................................................................................................... 32 Criminal Records (Expungement of Convictions for Historical Homosexual Offences) Bill. ... 45 Domestic Violence-Victims’ Protection Bill ............................................................................. 60 The Electoral (Integrity) Amendment Bill ................................................................................ 75 Parliamentary scrutiny of human rights in New Zealand: Summary report. .......................... 89 1 Introduction This research is a focused project on one aspect of the parliamentary process. It provides a contextualised account of select committees and their scrutiny of human rights with a particular -

I Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic

Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic Institutions. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the University of Canterbury by R.M.Farquhar University of Canterbury 2006 I Contents. Abstract...........................................................................................................VI Introduction....................................................................................................VII Methodology....................................................................................................XIX Part 1. Chapter 1 Critical Theory: Conflict and change, marxism, Horkheimer, Adorno, critique of positivism, instrumental reason, technocracy and the Enlightenment...................................1 1.1 Mannheim’s rehabilitation of ideology and politics. Gramsci and social and political change, hegemony and counter-hegemony. Laclau and Mouffe and radical plural democracy. Talshir and modular ideology............................................................................11 Part 2. Chapter 2 Liberal Democracy: Dryzek’s tripartite conditions for democracy. The struggle for franchise in Britain and New Zealand. Extra-Parliamentary and Parliamentary dynamics. .....................29 2.1 Technocracy, New Zealand and technocracy, globalisation, legitimation crisis. .............................................................................................................................46 Chapter 3 Liberal Democracy-historical -

An Economic Perspective on the Law: Is There "Legal Failure"?

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. An economic perspective on the law: Is there ―legal failure‖? A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Economics at Massey University, Palmerston North New Zealand. Keith Stuart Birks 2011 i COPYRIGHT Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ii Abstract The law fulfils important functions in society, contributing to its institutional structure, its policies and resolution of disputes. Workers employed in the law are providing a service, and economics can be applied to analyse the nature of this service. Such analysis must recognise the characteristics of law, including the costs and nature of deliberation. This requires more than the use of theoretical approaches which assume exogenous preferences and no transaction costs. Rhetoric is important in law, and there may be a rhetorical dimension to economics itself. This theme has led to the thesis having two components. The first considers methodological issues in the application of theories and techniques. The second then assesses aspects of the law. Groups and group cultures are considered as influences on academic disciplines including economics, and professions such as the law, as well as shaping political activity and social beliefs. -

Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election

References Achen, Christopher and Larry Bartels. 2016. Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Adams, James. 2001. Party competition and responsible party government. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Adams, James. 2012. Causes and electoral consequences of party policy shifts in multiparty elections: Theoretical results and empirical evidence. Annual Review of Political Science 15: 401–19. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-031710-101450 Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswick, Daniel J. Levinson and R. Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The authoritarian personality. Oxford: Harpers. Aimer, Peter. 1989. Travelling together: Party identification and voting in the New Zealand general election of 1987. Electoral Studies 8(2): 131–42. DOI: 10.1016/0261-3794(89)90030-9 Aimer, Peter. 1993. Was there a gender gap in New Zealand in 1990? Political Science 45(1): 112–21. DOI: 10.1177/003231879304500108 Aimer, Peter. 1998. Old and new party choices. In Jack Vowles, Peter Aimer, Susan Banducci and Jeffrey Karp, eds, Voters’ victory? New Zealand’s first election under proportional representation, 48–64. Auckland: Auckland University Press. Aimer, Peter. 2014. New Zealand’s electoral tides in the 21st century. In Jack Vowles, ed., The new electoral politics in New Zealand: The significance of the 2011 Election, 9–25. Wellington: Institute for Governance and Policy Studies. 281 A BARk BuT No BITE Albrecht, Johan. 2006. The use of consumption taxes to re-launch green tax reforms. International Review of Law and Economics 26(1): 88–103. DOI: 10.1016/j.irle.2006.05.007 Alesina, Alberto and Eliana La Ferrara. -

Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election

A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION JACK VOWLES, HILDE COFFÉ AND JENNIFER CURTIN Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Vowles, Jack, 1950- author. Title: A bark but no bite : inequality and the 2014 New Zealand general election / Jack Vowles, Hilde Coffé, Jennifer Curtin. ISBN: 9781760461355 (paperback) 9781760461362 (ebook) Subjects: New Zealand. Parliament--Elections, 2014. Elections--New Zealand. New Zealand--Politics and government--21st century. Other Creators/Contributors: Coffé, Hilde, author. Curtin, Jennifer C, author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of figures . vii List of tables . xiii List of acronyms . xvii Preface and acknowledgements . .. xix 1 . The 2014 New Zealand election in perspective . .. 1 2. The fall and rise of inequality in New Zealand . 25 3 . Electoral behaviour and inequality . 49 4. The social foundations of voting behaviour and party funding . 65 5. The winner! The National Party, performance and coalition politics . 95 6 . Still in Labour . 117 7 . Greening the inequality debate . 143 8 . Conservatives compared: New Zealand First, ACT and the Conservatives . -

Helen Clark Must Do More To

Socialist Worker Monthly Review #6 • April 2003 • $2 Helen Clark must do more to STOP the WAR! ■ Withdraw the frigate ■ Condemn the invasion Inside: ● Green MP Keith Locke, Labour councillor Greg Presland and Socialist Worker’s Grant Brookes debate “What more can Labour do?” ● Burning the flag ● Direct action debates ● Plus: Kinleith strike, Prostitution Reform Bill, & more. Socialist Worker Monthly Review April 2003 1 What’s on APRIL 12 WHO SAYS? International Day of “Resistance has Action Against the War been minimal Details available as Socialist ■ WELLINGTON protest action. Details to be becausec few Iraqis Worker Monthly Review Peace Action Wellington have confirmed. Contact Brian, will fight for goes to press: called a protest for either 472 7473 or Fiona Saddam – and even April 11 (Friday night) or April [email protected]. ■ AUCKLAND 12. Further details to be fewer will die for Gather at 12 noon, Western confirmed. Contact Grant, 566 ■ OTHER CENTRES him.” Park (corner Ponsonby Rd & K 8538 or e-mail Information on actions in Richard Perle, key Rd). [email protected] other centres will be posted Pentagon advisor to Organised by Global Peace & by Peace Movement Aotearoa Justice Auckland. ■ DUNEDIN as it becomes available, George Bush. For more information, phone Dunedin Coalition Against www.converge.org.nz/pma/ 361 6989. the War will be organising date.htm “Our forces will be met with applause and sweets and flowers.” Pentagon official. “I’m not fighting for Saddam Hussein, I’m fighting for Iraq.” Nasr Al Hussein, one of hundreds of Iraqi exiles queuing to board coaches in WASHINGTON LONDON AUCKLAND Jordan to return to Baghdad. -

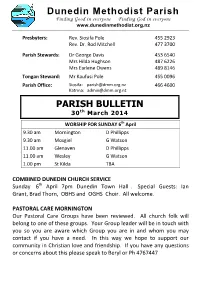

Dunedin Methodist Parish Finding Good in Everyone Finding God in Everyone

Dunedin Methodist Parish Finding Good in everyone Finding God in everyone www.dunedinmethodist.org.nz Presbyters: Rev. Siosifa Pole 455 2923 Rev. Dr. Rod Mitchell 477 3700 Parish Stewards: Dr George Davis 453 6540 Mrs Hilda Hughson 487 6226 Mrs Earlene Owens 489 8146 Tongan Steward: Mr Kaufusi Pole 455 0096 Parish Office: Siosifa: [email protected] 466 4600 Katrina: [email protected] PARISH BULLETIN th 30 March 2014 th WORSHIP FOR SUNDAY 6 April 9.30 am Mornington D Phillipps 9.30 am Mosgiel G Watson 11.00 am Glenaven D Phillipps 11.00 am Wesley G Watson 1.00 pm St Kilda TBA COMBINED DUNEDIN CHURCH SERVICE Sunday 6th April 7pm Dunedin Town Hall . Special Guests: Ian Grant, Brad Thorn, OBHS and OGHS Choir. All welcome. PASTORAL CARE MORNINGTON Our Pastoral Care Groups have been reviewed. All church folk will belong to one of these groups. Your Group leader will be in touch with you so you are aware which Group you are in and whom you may contact if you have a need. In this way we hope to support our community in Christian love and friendship. If you have any questions or concerns about this please speak to Beryl or Ph 4767447 2 EXPLORERS GROUP meets on Sunday 30th March, at 4.30pm in the Mornington Church Lounge, where our intended topic is Further discussion of future directions for the parish. All interested people welcome to join us. MOSGIEL METHODIST WOMEN’S FELLOWSHIP Tuesday 1st April at 1:30pm in the church when Max Quinn from The Natural History Department will be speaking to us.