Outlawing Shark Finning Throughout Global Waters Jessica Spiegel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—House H8792

H8792 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE December 21, 2010 The Shark Conservation Act would end the The SPEAKER pro tempore. The revolving loans, as determined by the Adminis- practice of shark finning in U.S. waters. question is on the motion offered by trator, on a competitive basis, to eligible entities, However, domestic protections alone will not the gentlewoman from Guam (Ms. including through contracts entered into under save sharks. subsection (e) of this section,’’; and BORDALLO) that the House suspend the (B) in paragraph (1), by striking ‘‘tons of’’; We need further safeguards to keep marine rules and concur in the Senate amend- (3) in subsection (b)— ecosystems and top predator populations ment to the bill, H.R. 81. (A) by striking paragraph (2); healthy. The Shark Conservation Act will bol- The question was taken; and (two- (B) by redesignating paragraph (3) as para- ster the U.S.’s position when negotiating for thirds being in the affirmative) the graph (2); and increased international fishery protections. rules were suspended and the Senate (C) in paragraph (2) (as so redesignated)— (i) in subparagraph (A), in the matter pre- Healthy shark populations in our waters can amendment was concurred in. help drive our economy and make our seas ceding clause (i), by striking ‘‘90’’ and inserting A motion to reconsider was laid on ‘‘95’’; thrive. the table. This bill is not just about preserving a spe- (ii) in subparagraph (B)(i), by striking ‘‘10 f percent’’ and inserting ‘‘5 percent’’; and cies, but about preserving an ecosystem, an (iii) in subparagraph (B)(ii), by striking ‘‘the economy, and a sustainable future. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

NOAA Testimony

WRITTEN TESTIMONY BY ALAN RISENHOOVER, DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES, NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE, NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE HEARING ON LEGISLATION ON SHARK FIN AND BILLFISH SALES BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES SUBCOMMITTEE ON WATER, POWER AND OCEANS U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES April 17, 2018 Introduction Good afternoon, Chairman Lamborn, Ranking Member Huffman, and Members of the Subcommittee. My name is Alan Risenhoover and I am the Director of the Office of Sustainable Fisheries within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) in the Department of Commerce. Shark and billfish species are important contributors to the nation’s valuable commercial and recreational fisheries as well as serving an important role in our ocean ecosystem. I appreciate the opportunity to speak with you today about the work by NMFS to conserve and manage sharks and billfish and to provide our perspective on the main bills being discussed. Shark Conservation and Management Almost two decades ago Congress prohibited shark finning—which is removing shark fins at sea and discarding the rest of the shark—when it amended the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act by enacting the Shark Finning Prohibition Act of 2000. The law prohibits any person under U.S. jurisdiction from engaging in the finning of sharks, possessing shark fins aboard a fishing vessel without the corresponding carcass, and landing shark fins without the corresponding carcass. In 2008, NOAA implemented even more stringent regulations to require all Atlantic sharks to be landed with all fins naturally attached to facilitate species identification and reporting and improve the enforceability of existing shark management measures, including the finning ban. -

Fishing for Sharks History of Shark Finning Protection Towards Sharks Importance of Sharks Sharks Are a Top Predator of the Ocean

Shark Finning Tiana Barron-Wright Fishing for Sharks History of Shark Finning Protection Towards Sharks Importance of Sharks Sharks are a top predator of the ocean. However, sharks are a target Shark fin soup originated in 968 AD by an emperor from the Sung The Shark Finning Prohibition Act of 2000, was signed by former Sharks play an important role in the ecosystem. Sharks maintain the for humans. Shark finning is the process of cutting off a shark’s Dynasty. The emperor created shark fin soup to display his wealth, President Bill Clinton. This act prohibited the process of shark finning in species below them in the ecosystem and serve as a health indicator for the fins while it is still alive and throwing the shark back into the power and generosity towards his guest. Serving shark fin soup the United States. This bans anyone in the United States jurisdiction from ocean. The decrease of sharks in the oceans has led to the decline of coral ocean where it will die. After getting their fins cut off, some sharks shark finning, owning shark fins without the shark’s body, and landing reefs, sea grass beds, and the loss of commercial fisheries. Without sharks was seen as a show of respect. Chinese Emperors thought the dish in the ecosystem, other predators can thrive. For example, groupers can can starve to death, get eaten by other fish or drown to death. shark fins without the body. This act also has NOAA (National Oceanic had medicinal benefits. Shark fin soup is considered a delicacy in and Atmospheric Administration) Fisheries to give Congress a report increase in numbers and eat herbivores. -

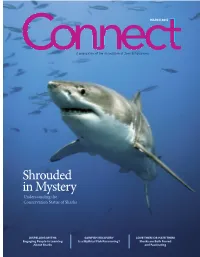

Shrouded in Mystery Understanding the Conservation Status of Sharks

MARCH 2015 A publication of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums Shrouded in Mystery Understanding the Conservation Status of Sharks DISPELLING MYTHS SAWFISH RECOVERY LOVE THEM OR HATE THEM Engaging People in Learning Is a Mythical Fish Recovering? Sharks are Both Feared About Sharks and Fascinating March 2015 Features 18 24 30 36 Shrouded in Mystery Dispelling Myths Sawfi sh Recovery Love Them or Hate Them The International Union for Through informative Once abundant in the Sharks are iconic animals Conservation of Nature Red displays, underwater waters of more than 90 that are both feared and List of Threatened Species tunnels, research, interactive countries around the world, fascinating. Misrepresented indicates that 181 of the touch tanks and candid sawfi sh are now extinct from in a wide array of media, the 1,041 species of sharks and conversations with guests, half of their former range, public often struggles to get rays are threatened with Association of Zoos and and all fi ve species are a clear understanding of the extinction, but the number Aquariums-accredited classifi ed as endangered complex and important role could be even higher. facilities have remarkable or critically endangered by that these remarkable fi sh play BY LANCE FRAZER ways of engaging people in the International Union for in oceans around the world. informal and formal learning. Conservation of Nature. BY DR. SANDRA ELVIN AND BY KATE SILVER BY EMILY SOHN DR. PAUL BOYLE March 2015 | www.aza.org 1 7 13 24 Member View Departments 7 County-Wide Survey 9 Pizzazz in Print 11 By the Numbers 44 Faces & Places Yields No Trace of Rare This Vancouver Aquarium ad AZA shark and ray 47 Calendar Western Pond Turtle was one of fi ve that ran as conservation. -

Sharks in the Seas Around Us: How the Sea Around Us Project Is Working to Shape Our Collective Understanding of Global Shark Fisheries

Sharks in the seas around us: How the Sea Around Us Project is working to shape our collective understanding of global shark fisheries Leah Biery1*, Maria Lourdes D. Palomares1, Lyne Morissette2, William Cheung1, Reg Watson1, Sarah Harper1, Jennifer Jacquet1, Dirk Zeller1, Daniel Pauly1 1Sea Around Us Project, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada 2UNESCO Chair in Integrated Analysis of Marine Systems. Université du Québec à Rimouski, Institut des sciences de la mer; 310, Allée des Ursulines, C.P. 3300, Rimouski, QC, G5L 3A1, Canada Report prepared for The Pew Charitable Trusts by the Sea Around Us project December 9, 2011 *Corresponding author: [email protected] Sharks in the seas around us Table of Contents FOREWORD........................................................................................................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 SHARK BIODIVERSITY IS THREATENED ............................................................................. 10 SHARK-RELATED LEGISLATION ............................................................................................. 13 SHARK FIN TO BODY WEIGHT RATIOS ................................................................................ 14 -

Anthrozoology and Sharks, Looking at How Human-Shark Interactions Have Shaped Human Life Over Time

Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2020 Committee: Marc L. Miller, Chair Vincent F. Gallucci Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Marine and Environmental Affairs © Copywrite 2020 Jessica O’Toole 2 University of Washington Abstract Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthrozoology is a relatively new field of study in the world of academia. This discipline, which includes researchers ranging from social studies to natural sciences, examines human-animal interactions. Understanding what affect these interactions have on a person’s perception of a species could be used to create better conservation strategies and policies. This thesis uses a mixed qualitative methodology to examine the public perception of great white sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While the area has a history of shark interactions, a shark related death in 2018 forced many people to re-evaluate how they view sharks. Not only did people express both positive and negative perceptions of the animals but they also discussed how the attack caused them to change their behavior in and around the ocean. Residents also acknowledged that the sharks were not the only problem living in the ocean. They often blame seals for the shark attacks, while also claiming they are a threat to the fishing industry. -

Shark Finning Script

This episode is brought to you by Pool Industries at Seattle University, producer of one-of-a-kind aquariums and plankton columns, good for the lab AND the home *wink* Define the challenge (Basic introduction to the topic) Jenna Rolf: So Karyssa... Ever heard of sharks? Karyssa Miller: To be honest Jen, I’ve never seen one in real life, but I did have a plastic toy as a kid! JR: Well let me tell you - they’re pretty neat. They’re top predators, meaning that they play a very important role in marine ecosystems and have no natural predators. KM: You mean they’re more than just that scary shark in Jaws that tries to eat everyone???? JR: Exactly. It’s actually the other way around - humans are the ones that are threatening sharks. In fact, humans kill an estimated 100 million sharks every year. This mostly happens through shark finning, which is a practice that involves cutting the fin off of the shark carcass, typically for shark fin soup or medicinal practices. KM: Yeah, the entire body is not needed since shark meat is not as profitable as the fin. Shark fins can reach prices of over $300/lb, making this one of the highest priced food sources in the world JR: Shark fin soup consumption is one of the leading causes of global shark decline. Fins first appeared as a delicacy in Chinese cuisine thousands of years ago around the year 960 and were later established as a luxury food item. KM: Obviously this is not a great practice for the sharks specifically, but it also affects marine ecosystems as a whole. -

Portland's Fritzi Cohen Didn't Have to Be Asked Twice to Join the Cast Of

Swimming Fritzi Cohen’s big fish story is no exaggeration. Portland’s Fritzi Cohen didn’t have to be asked twice to join the cast of Jaws…she was askedf it’s summer three in New England, times. you’ve got to be thinking Jaws. Especially if it’s Ithe summer of 2012, when Universal Studios is behind a monster clambake on Martha’s Vineyard from August 9-12 called “JAWSFEST: The Tribute.” Sponsored by MV Promotions Networks, the event will celebrate Universal’s 100th anniversary as well as the cast and crew of this frighteningly successful film. While the late Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Jaws author Peter Benchley will sadly miss the BBQ, the event will still be thronged by well-wishers and fans hoping for glimpses of original cast mem- bers Richard Dreyfuss (Hooper), Susan Backlinie (Chrissie, the most famous night- swimming shark attack victim ever), Lee Fierro (Mrs. Kintner), and possibly Maine’s Fritzi Cohen (under the stage name of Fritzi Jane Courtney), who made the most of her part as a selectwoman in the fictional town of Amity. She reprised her role as Mrs. Taft 1 1 6 p o r t l a n d monthly magazine c l a ssi c S With the Swimming Sharksfrom staff & wire reports Roy Scheider, far left, Murray Hamilton, and Fritzi Cohen grab audience attention during the emergency town council scene in Jaws. in both Jaws 2 (1978) and Jaws: The i’d’d justjust beenbeen working onon Lenny Revenge (1987). Faced with tourism reve- at Charles playhouse inin Boston e C i nues in free fall because of great ff when i got the call to audition. -

Sustainable Trade in Sharks

Action Plan for North America Sustainable Trade in Sharks Commission for Environmental Cooperation Please cite as: CEC. 2017. Sustainable Trade in Sharks: Action Plan for North America. Montreal, Canada: Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 56 pp. This report was prepared by Ernest W.T. Cooper and Óscar Sosa-Nishizaki, of E. Cooper Environmental Consulting, for the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). The information contained herein is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the governments of Canada, Mexico or the United States of America. Reproduction of this document in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes may be made without special permission from the CEC Secretariat, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. The CEC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication or material that uses this document as a source. Except where otherwise noted, this work is protected under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial–No Derivative Works License. © Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2017 Publication Details Publication type: Project Publication Publication date: May 2017 Original language: English Review and quality assurance procedures: Final Party review: April 2017 QA312 Project: 2015-2016/Strengthening conservation and sustainable production of selected CITES Appendix II species in North America ISBN: 978-2-89700-193-3 (e-version); 978-2-89700-194-0 (print) Disponible en français (sommaire de rapport) – ISBN: -

Examining the Regulation of Shark Finning in the United States

EXAMINING THE REGULATION OF SHARK FINNING IN THE UNITED STATES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE INTERIOR, ENERGY, AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION November 2, 2017 Serial No. 115–51 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://oversight.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–612 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:54 Mar 29, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\28612.TXT APRIL KING-6430 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM Trey Gowdy, South Carolina, Chairman John J. Duncan, Jr., Tennessee Elijah E. Cummings, Maryland, Ranking Darrell E. Issa, California Minority Member Jim Jordan, Ohio Carolyn B. Maloney, New York Mark Sanford, South Carolina Eleanor Holmes Norton, District of Columbia Justin Amash, Michigan Wm. Lacy Clay, Missouri Paul A. Gosar, Arizona Stephen F. Lynch, Massachusetts Scott DesJarlais, Tennessee Jim Cooper, Tennessee Trey Gowdy, South Carolina Gerald E. Connolly, Virginia Blake Farenthold, Texas Robin L. Kelly, Illinois Virginia Foxx, North Carolina Brenda L. Lawrence, Michigan Thomas Massie, Kentucky Bonnie Watson Coleman, New Jersey Mark Meadows, North Carolina Stacey E. Plaskett, Virgin Islands Ron DeSantis, Florida Val Butler Demings, Florida Dennis A. -

Great White Sharks Thinkcentral.Com Magazine Article by Peter Benchley

Before Reading Video link at Great White Sharks thinkcentral.com Magazine Article by Peter Benchley Can you tell FACT from fiction? Artists and writers often use what they know to be true about the world to create imaginary scenarios that can seem more real than RI 6 Determine an author’s point of view and analyze how the life itself. But how do you know when a work of fiction is technically author distinguishes his position. RI 8 Trace specific claims in a accurate and when it’s not? Peter Benchley has made a name for text. himself by dealing in both facts and fiction about great white sharks. LIST IT Choose a movie or a book you have enjoyed Homeward Bound that features animals or natural events. For each movie or book, list some of the details that were 1. Animals can find included, explaining whether they’re true or not. their way home across hundreds of miles. 2. 3. 4. 918 918-919_NA_L07PE-u08s2-brWhit.indd 918 1/12/11 12:47:16 AM Meet the Author text analysis: evidence in informational text Writers of informational text usually support their claims Peter Benchley with evidence, such as facts, which are statements that can 1940–2006 be proved. Be sure that you can tell the difference between The Jaws Sensation factual claims and opinions or commonplace assertions. Peter Benchley is best known for his • A factual claim is a statement that can be proved from novel Jaws, which is about the hunt evidence such as a fact, personal observation, reliable for a great white shark that killed source, or an expert’s opinion.