The Search for Extra-Terrestial Intelligence in the New Millennium Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of the Arecibo Radio Telescope

DYNAMICS OF THE ARECIBO RADIO TELESCOPE Ramy Rashad 110030106 Department of Mechanical Engineering McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada February 2005 Under the supervision of Professor Meyer Nahon Abstract The following thesis presents a computer and mathematical model of the dynamics of the tethered subsystem of the Arecibo Radio Telescope. The computer and mathematical model for this part of the Arecibo Radio Telescope involves the study of the dynamic equations governing the motion of the system. It is developed in its various components; the cables, towers, and platform are each modeled in succession. The cable, wind, and numerical integration models stem from an earlier version of a dynamics model created for a different radio telescope; the Large Adaptive Reflector (LAR) system. The study begins by converting the cable model of the LAR system to the configuration required for the Arecibo Radio Telescope. The cable model uses a lumped mass approach in which the cables are discretized into a number of cable elements. The tower motion is modeled by evaluating the combined effective stiffness of the towers and their supporting backstay cables. A drag model of the triangular truss platform is then introduced and the rotational equations of motion of the platform as a rigid body are considered. The translational and rotational governing equations of motion, once developed, present a set of coupled non-linear differential equations of motion which are integrated numerically using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta integration scheme. In this manner, the motion of the system is observed over time. A set of performance metrics of the Arecibo Radio Telescope is defined and these metrics are evaluated under a variety of wind speeds, directions, and turbulent conditions. -

SETI@Home Completes a Decade of ET Search 1 May 2009

SETI@home completes a decade of ET search 1 May 2009 Over the years, improvements to the Arecibo telescope have significantly improved the quality of data available to SETI@home, and the continuous increase in the speed of the average PC has made it possible to use more sensitive and sophisticated analysis techniques. Today, SETI@home continues its search for evidence of extraterrestrial life, with greater sensitivity than ever, and its hundreds of thousands of volunteers continue to engage in lively on-line forums and in a spirited competition The SETI@home project, which has involved the for most data processed. worldwide public in a search for radio-wave evidence of life outside Earth, marks its 10th More information: anniversary on May 17, 2009. setiathome.berkeley.edu/index.php The project, based at the Space Sciences Provided by SETI@home Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, records and analyzes data from the world's largest radio telescope, the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. The collected computing power of hundreds of thousands of volunteer PCs is used to search this data for narrow-band signals (similar to TV or cell-phone transmissions) and other types of signals of possible extraterrestrial origin. SETI@home was conceived in 1995. Development began in 1998, with initial funding from The Planetary Society and Paramount Pictures. It was publicly launched on May 17, 1999, and the number of volunteers quickly grew to about one million. Because of the presence of noise and man-made radio interference, SETI@home doesn't get excited by individual signals. -

Why SETI Will Fail ‡

Why SETI Will Fail z B. Zuckerman1 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The union of space telescopes and interstellar spaceships guarantees that if extraterrestrial civilizations were common, someone would have come here long ago. PACS numbers: 97.10.Tk arXiv:1912.08386v1 [physics.pop-ph] 18 Dec 2019 z This article originally appeared in the September/October 2002 issue of Mercury magazine (published by the Astronomical Society of the Pacific). Why SETI Will Fail 2 1. Introduction Where do humans stand on the scale of cosmic intelligence? For most people, this question ranks at or very near the top of the list of "scientific things I would like to know." Lacking hard evidence to constrain the imagination, optimists conclude that technological civilizations far in advance of our own are common in our Milky Way Galaxy, whereas pessimists argue that we Earthlings probably have the most advanced technology around. Consequently, this topic has been debated endlessly and in numerous venues. Unfortunately, significant new information or ideas that can point us in the right direction come along infrequently. But recently I have realized that important connections exist between space astronomy and space travel that have never been discussed in the scientific or popular literature. These connections clearly favor the more pessimistic scenario mentioned above. Serious radio searches for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) have been conducted during the past few decades. Brilliant scientists have been associated with SETI, starting with pioneers like Frank Drake and the late Carl Sagan and then continuing with Paul Horowitz, Jill Tarter, and the late Barney Oliver. -

Nasa and the Search for Technosignatures

NASA AND THE SEARCH FOR TECHNOSIGNATURES A Report from the NASA Technosignatures Workshop NOVEMBER 28, 2018 NASA TECHNOSIGNATURES WORKSHOP REPORT CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What are Technosignatures? .................................................................................................................................... 2 What Are Good Technosignatures to Look For? ....................................................................................................... 2 Maturity of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Breadth of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Limitations of This Document .................................................................................................................................... 6 Authors of This Document ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 EXISTING UPPER LIMITS ON TECHNOSIGNATURES ....................................................................................................... 9 Limits and the Limitations of Limits ........................................................................................................................... -

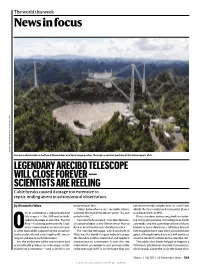

News in Focus ARECIBO OBSERVATORY/UNIV

The world this week News in focus ARECIBO OBSERVATORY/UNIV. CENTRAL FLORIDA CENTRAL OBSERVATORY/UNIV. ARECIBO A main cable broke in half on 6 November and tore large gashes through a central portion of the telescope’s dish. LEGENDARY ARECIBO TELESCOPE WILL CLOSE FOREVER — SCIENTISTS ARE REELING Cable breaks caused damage too extensive to repair, ending an era in astronomical observation. By Alexandra Witze mourning its loss. extraterrestrials might hear it, and from “I don’t know what to say,” says Robert Kerr, which the first confirmed extrasolar planet ne of astronomy’s most renowned a former director of the observatory. “It’s just was discovered, in 1992. tele scopes — the 305-metre-wide unbelievable.” It has also done pioneering work in explor- radio telescope at Arecibo, Puerto “I am totally devastated,” says Abel Méndez, ing many phenomena, including near-Earth Rico — is closing permanently. Engi- an astrobiologist at the University of Puerto asteroids and the puzzling celestial blasts neers cannot find a safe way to repair Rico at Arecibo who uses the observatory. known as fast radio bursts. All those lines of Oit, after two cables supporting the structure The Arecibo telescope, which was built in investigation have now been shut down for broke suddenly and catastrophically, one in 1963, was the world’s largest radio telescope good, although limited science will continue August and one in early November. for decades and has historical and modern at some smaller facilities on the Arecibo site. It is the end of one of the most iconic and importance in astronomy. It was the site The cables that broke helped to support a scientifically productive telescopes in the from which astronomers sent an inter stellar 900-tonne platform of scientific instruments, history of astronomy — and scientists are radio message in 1974, in the hope that any which hangs above the main telescope dish. -

Dr. Steve Croft UC Berkeley Department of Astronomy, 501 Campbell Hall #3411, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

Dr. Steve Croft UC Berkeley Department of Astronomy, 501 Campbell Hall #3411, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA PERSONAL DETAILS Citizenships: USA and UK dual national Professional Memberships: Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, Member of the American Astronomical Society, Member of the International Astronomical Union, Member of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Member of the International Academy of Astronautics Permanent Committee on SETI EDUCATION 1998 – 2002 Oxford University, UK: DPhil (PhD) Astrophysics Galaxy clustering at high redshift from radio surveys. Advisor: Steve Rawlings 1994 – 1998 University College London (London University), UK: MSci Astrophysics MSci project: Magnetism and Accretion in AM Herculis Degree class: First class honours 1987 – 1994 Calday Grange Grammar School, UK (1994) A-level: Physics: A, Mathematics: A, Further Mathematics: B, Geography: A, General Studies: A, Music: C (best A-level results in school) (1993) AO: German for Business Studies: A (1992) GCSE: 10 Grade A, 1 Grade B (best GCSE results in school) (1991) GCSE: Mathematics: A EMPLOYMENT 2016 to date Associate Project Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley / Scientist VI, Eureka Scientific Project Scientist for the Breakthrough Listen project on the Green Bank Telescope. Leading the outreach, education, undergraduate internship (PI: NSF REU), industry and community engagement, and public data programs, in addition to proposal writing and scientific data analysis, for UC Berkeley SETI Research Center and for Breakthrough Listen. 2021 to date Adjunct Senior Scientist, SETI Institute (additional affiliation to UCB) Science with the Allen Telescope Array. Community Partnerships for SETI. 2012 – 2013 Researcher, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (with David Kaplan) - based at UCB Transient searches with the Very Large Array and the Murchison Widefield Array. -

Technosignature Report Final 121619

NASA AND THE SEARCH FOR TECHNOSIGNATURES A Report from the NASA Technosignatures Workshop NOVEMBER 28, 2018 NASA TECHNOSIGNATURES WORKSHOP REPORT CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 What are Technosignatures? .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 What Are Good Technosignatures to Look For? ....................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Maturity of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Breadth of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Limitations of This Document .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.6 Authors of This Document ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 EXISTING UPPER LIMITS ON TECHNOSIGNATURES ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Limits and the Limitations of Limits ........................................................................................................................... -

Ground Based, Space Based, Infrastructure, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities

Ground Based, Space Based, Infrastructure, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Ground Based, Space Based, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Ground Based, Space Based, and Technological Development Activities Ground Based and Space Based Activities Ground Based, Infrastructure, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Ground Based, Infrastructure, Technological Development, State of the Profession, and Other Activities Ground Based, Infrastructure, and Technological Development Activities Ground Based, Infrastructure, and State of the Profession Activities Ground Based and Infrastructure Activities Ground Based, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Ground Based and Technological Development Activities Ground Based Projects Space Based, Infrastructure, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Space Based, Infrastructure, Technological Development Activities Space Based and Infrastructure Activities Space Based, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Space Based and Technological Development Activities Space Based and State of the Profession Activities Space Based Projects Infrastructure, Technological Development, and State of the Profession Activities Infrastructure, Technological Development, and Other Activities Infrastructure and Technological Development Activities Infrastructure, State of the Profession, and Other Activities Infrastructure and State of the Profession -

Activity Report December 2017 the CARL SAGAN CENTER for RESEARCH Dr

Activity Report December 2017 THE CARL SAGAN CENTER FOR RESEARCH Dr. Nathalie A. Cabrol, Director 2 Peer-Reviewed Publications 1. Barge, L. M., F. C. Krause, J.-P. Jones, K. Billings, and P. Sobron, Geo-Electrodes and Fuel Cells for Simulating Hydrothermal Vent Environments, Astrobiology (submitted). 2. Cabrol, N.A. The coevolution of life & environment on Mars: An ecosystem perspective on the robotic exploration of biosignatures, Astrobiology, 18 (1), January 2018 (in press). The article will be on Open Access soon. 3. Cabrol, N.A. Introduction to From Habitability to Life on Mars, In: From Habitability to Life on Mars, Cabrol, N.A., and E. A. Grin, eds., Elsevier, in press. 4. Cabrol, N.A., E. A. Grin, P. Zippi, N. Noffke, and D. Winter, Evolution of Altiplanic Lake Habitats and Biosignatures at the Pleistocene/Holocene Transition, In: From Habitability to Life on Mars, Cabrol, N.A., and E. A. Grin, eds., Elsevier, in press. 5. Etcheverria, A., et al., (including Cabrol, N.A.). Discrepancies in microbial and limnological response to climate change of close-related Andean oligotrophic lakes triggered by watershed characteristics. Geobiology, 2017 (in press). 6. Hendler NP, Pinilla P, Pascucci I, Pohl A, Mulders G, et al., including Hollenbach D (2017) A likely planet-induced gap in the disk around T Cha. Accepted to MNRAS letters. 7. Iuvan, I. G., Lendl, M., Cubillos, P. E., Tregloan-Reed, J., Lammer, H., Guenther, E. W., and Hanslmeier, A. Pytranspot – A tool for multiband light curve modeling of planetary transits and stellar spots. A&A, in press: http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017arXiv171011209J 8. -

Developments in North America at Longer Wavelengths

DEVELOPMENTS IN NORTH AMERICA AT LONGER WAVELENGTHS Peter J. Napier National Radio Astronomy Observatory PO Box 0, Socorro, NM 87801, US. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The instruments currently operating or planned for centimeter and longer wavelengths in Canada and the United States are briefly reviewed. References to on-line documents are provided for readers wanting more detailed information about these observatories. INTRODUCTON A number of observatories and projects are currently active in providing radio astronomical observing capabilities at centimeter and longer wavelengths in Canada and the United States. These activities are briefly reviewed for each observatory or project, listed in alphabetical order. Where available, references to on-line documents are provided for those readers interested in more detail concerning the current status of these activities . ALLEN TELESCOPE ARRAY PROJECT (ATA) The ATA [1] is a joint project between the SETI Institute and the University of California at Berkeley Radio Astronomy Lab (RAL). The ATA will consist of approximately three hundred and fifty 6.1-meter diameter offset Gregorian dishes arrayed on baselines from 11 to 700 m at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory. The radio frequency (RF) range accessible for observations will be 0.5- 11.2 GHz. Planned outputs from the array include up to 16 phased-array beams each with a bandwidth of 100 MHz and visibility functions from a 350 station correlator. A number of innovative designs are being used to keep the cost significantly below the cost of previous arrays of this size. Some of the new technologies include: antenna surfaces fabricated in a single piece by hydroforming, a single feed and cryogenically cooled receiver covering the full RF band, return of the full RF band to the central building using an analog fiber-optic link. -

Are We Alone? the Search for Life Beyond the Earth Transcript

Are We Alone? The search for life beyond the Earth Transcript Date: Wednesday, 24 September 2014 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 24 September 2014 Are we Alone? The Search for Life beyond the Earth Professor Ian Morison We have three possibilities, firstly to find evidence of present or past life on other planets or satellites of our own solar system, secondly to find evidence of life in nearby solar systems and thirdly to detect a signal from another advance civilisation in what is called SETI – the Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence. Let’s work our way outwards into the galaxy. A Civilisation on Mars? Mars was first seen through a telescope by Galileo in 1609, but his small telescope showed no surface details. When Mars was at its closet to Earth in 1877, an Italian astronomer, Giovanni Schiaparelli, used a 22-cm telescope to chart its surface and produce the first detailed maps. They contained linear features which Schiaparelli called canali, the Italian for channel. However this was translated into English as “canal”− which implies a man made water course − and the feeling arose that Mars might be inhabited by an intelligent race. It should be pointed that a waterway could not be detected from Earth, but it was thought that these would have been used for irrigation and so would have irrigated crops growing adjacent to them which could be seen from Earth. Influenced by Schiaparelli’s observations, Percival Lowell founded an observatory at Flagstaff Arizonia (later famous for the discovery of Pluto) where he made detailed observations of Mars which showed an intricate grid of canals. -

The SERENDIP III 70 Cm Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

DRAFT VERSION NOVEMBER 15, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 THE SERENDIP III 70 CM SEARCH FOR EXTRATERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE STUART BOWYER,MICHAEL LAMPTON,ERIC KORPELA,JEFF COBB,MATT LEBOFSKY, AND DAN WERTHIMER Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Draft version November 15, 2018 ABSTRACT We employed the SERENDIP III system with the Arecibo radio telescope to search for possible artificial ex- traterrestrial signals. Over the four years of this search we covered 93% of the sky observable at Arecibo at least once and 44% of the sky five times or more with a sensitivity of ∼ 3×10−25Wm−2. The data were sent to a 4×106 channel spectrum analyzer. Information was obtained from over 1014 independent data points and the results were then analyzed via a suite of pattern detection algorithms to identify narrow band spectral power peaks that were not readily identifiable as the product of human activity. We separately selected data coincident with interesting nearby G dwarf stars that were encountered by chance in our sky survey for suggestions of ex- cess power peaks. The peak power distributions in both these data sets were consistent with random noise. We report upper limits on possible signals from the stars investigated and provide examples of the most interesting candidates identified in the sky survey. This paper was intended for publication in 2000 and is presented here without change from the version submitted to ApJS in 2000. Keywords: 1. INTRODUCTION pared, for example, with the SETI Institute targeted search), Early radio searches for extraterrestrial intelligence used our sensitivity is still substantial because of the large col- dedicated telescope time to search for emission from nearby lecting area of the Arecibo telescope and the outstanding re- stars (see Tarter 1991 for a partial listing, and Tarter 2001 for ceivers that are available for use with this instrument.