Are We Alone? the Search for Life Beyond the Earth Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of the Arecibo Radio Telescope

DYNAMICS OF THE ARECIBO RADIO TELESCOPE Ramy Rashad 110030106 Department of Mechanical Engineering McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada February 2005 Under the supervision of Professor Meyer Nahon Abstract The following thesis presents a computer and mathematical model of the dynamics of the tethered subsystem of the Arecibo Radio Telescope. The computer and mathematical model for this part of the Arecibo Radio Telescope involves the study of the dynamic equations governing the motion of the system. It is developed in its various components; the cables, towers, and platform are each modeled in succession. The cable, wind, and numerical integration models stem from an earlier version of a dynamics model created for a different radio telescope; the Large Adaptive Reflector (LAR) system. The study begins by converting the cable model of the LAR system to the configuration required for the Arecibo Radio Telescope. The cable model uses a lumped mass approach in which the cables are discretized into a number of cable elements. The tower motion is modeled by evaluating the combined effective stiffness of the towers and their supporting backstay cables. A drag model of the triangular truss platform is then introduced and the rotational equations of motion of the platform as a rigid body are considered. The translational and rotational governing equations of motion, once developed, present a set of coupled non-linear differential equations of motion which are integrated numerically using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta integration scheme. In this manner, the motion of the system is observed over time. A set of performance metrics of the Arecibo Radio Telescope is defined and these metrics are evaluated under a variety of wind speeds, directions, and turbulent conditions. -

SETI@Home Completes a Decade of ET Search 1 May 2009

SETI@home completes a decade of ET search 1 May 2009 Over the years, improvements to the Arecibo telescope have significantly improved the quality of data available to SETI@home, and the continuous increase in the speed of the average PC has made it possible to use more sensitive and sophisticated analysis techniques. Today, SETI@home continues its search for evidence of extraterrestrial life, with greater sensitivity than ever, and its hundreds of thousands of volunteers continue to engage in lively on-line forums and in a spirited competition The SETI@home project, which has involved the for most data processed. worldwide public in a search for radio-wave evidence of life outside Earth, marks its 10th More information: anniversary on May 17, 2009. setiathome.berkeley.edu/index.php The project, based at the Space Sciences Provided by SETI@home Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, records and analyzes data from the world's largest radio telescope, the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. The collected computing power of hundreds of thousands of volunteer PCs is used to search this data for narrow-band signals (similar to TV or cell-phone transmissions) and other types of signals of possible extraterrestrial origin. SETI@home was conceived in 1995. Development began in 1998, with initial funding from The Planetary Society and Paramount Pictures. It was publicly launched on May 17, 1999, and the number of volunteers quickly grew to about one million. Because of the presence of noise and man-made radio interference, SETI@home doesn't get excited by individual signals. -

Why SETI Will Fail ‡

Why SETI Will Fail z B. Zuckerman1 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The union of space telescopes and interstellar spaceships guarantees that if extraterrestrial civilizations were common, someone would have come here long ago. PACS numbers: 97.10.Tk arXiv:1912.08386v1 [physics.pop-ph] 18 Dec 2019 z This article originally appeared in the September/October 2002 issue of Mercury magazine (published by the Astronomical Society of the Pacific). Why SETI Will Fail 2 1. Introduction Where do humans stand on the scale of cosmic intelligence? For most people, this question ranks at or very near the top of the list of "scientific things I would like to know." Lacking hard evidence to constrain the imagination, optimists conclude that technological civilizations far in advance of our own are common in our Milky Way Galaxy, whereas pessimists argue that we Earthlings probably have the most advanced technology around. Consequently, this topic has been debated endlessly and in numerous venues. Unfortunately, significant new information or ideas that can point us in the right direction come along infrequently. But recently I have realized that important connections exist between space astronomy and space travel that have never been discussed in the scientific or popular literature. These connections clearly favor the more pessimistic scenario mentioned above. Serious radio searches for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) have been conducted during the past few decades. Brilliant scientists have been associated with SETI, starting with pioneers like Frank Drake and the late Carl Sagan and then continuing with Paul Horowitz, Jill Tarter, and the late Barney Oliver. -

The Search for Another Earth-Like Planet and Life Elsewhere Joshua Krissansen-Totton and David C

2 The Search for Another Earth-Like Planet and Life Elsewhere joshua krissansen-totton and david c. catling Introduction Is there life beyond Earth? Unlike most of the great cosmic questions pondered by anyone who has spent an evening of wonder beneath starry skies, this one seems accessible, perhaps even answerable. Other equally profound questions such as “Why does the universe exist?” and “How did life begin?” are perhaps more diffi- cult to address and must have complex explanations. But when one asks, “Is there life beyond Earth?” the answer is “Yes” or “No”. Yet despite the apparent simplic- ity, either conclusion would have profound implications. Few scientific discoveries have the power to reshape our sense of place inthe cosmos. The Copernican Revolution, the first such discovery, marked the birth of modern science. Suddenly, the Earth was no longer the center of the universe. This revelation heralded a series of findings that further diminished our perceived self- importance: the cosmic distance scale (Bessel, 1838), the true size of our galaxy (Shapley, 1918), the existence of other galaxies (Hubble, 1925), and finally, the large-scale structure and evolution of the cosmos. As Carl Sagan put it, “The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena” (Sagan, 1994, p. 6). Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection was the next perspective- shifting discovery. By providing a scientific explanation for the complexity and diversity of life, the theory of evolution replaced the almost universal belief that each organism was designed by a creator. Every species, including our own, was a small twig in an immense and slowly changing tree of life, driven by variation and natural selection. -

Nasa and the Search for Technosignatures

NASA AND THE SEARCH FOR TECHNOSIGNATURES A Report from the NASA Technosignatures Workshop NOVEMBER 28, 2018 NASA TECHNOSIGNATURES WORKSHOP REPORT CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What are Technosignatures? .................................................................................................................................... 2 What Are Good Technosignatures to Look For? ....................................................................................................... 2 Maturity of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Breadth of the Field ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Limitations of This Document .................................................................................................................................... 6 Authors of This Document ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 EXISTING UPPER LIMITS ON TECHNOSIGNATURES ....................................................................................................... 9 Limits and the Limitations of Limits ........................................................................................................................... -

The Search for Extra-Terrestial Intelligence in the New Millennium Transcript

The Search for Extra-Terrestial Intelligence in the New Millennium Transcript Date: Thursday, 3 April 2008 - 12:00AM THE SEARCH FOR EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM Professor Ian Morison SETI, the Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence, has now been actively pursued for close on 50 years without success. However this does not imply that we are alone in the Milky Way galaxy for, although most astronomers now agree that intelligent civilisations are far less common than once thought, we cannot say that there are none. But it does mean that they are likely to be at greater distances from us and, as yet, we have only seriously searched a tiny region of our galaxy. It will not be until the 2020's that an instrument, now on the drawing board, will give us the capability to detect radio signals of realistic power from across the whole galaxy. It is also possible that light, rather than radio, might be the communication carrier chosen by an alien race, but optical-SETI searches seeking out pulsed laser signals have only just begun. The story so far The subject may well have been inspired by the building of the 76m Mk1 radio telescope at Jodrell Bank in 1957. In 1959 two American astronomers, Guccione and Morrison, submitted a paper to the journal Nature in which they pointed out that, given two radio telescopes of comparable size to the Mk 1, it would be possible to communicate across interstellar distances by radio. They suggested a number of possible nearby, sun-like, stars that could be observed to see if any signals might be detected. -

Searches for Life and Intelligence Beyond Earth

Technologies of Perception: Searches for Life and Intelligence Beyond Earth by Claire Isabel Webb Bachelor of Arts, cum laude Vassar College, 2010 Submitted to the Program in Science, Technology and Society in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2020 © 2020 Claire Isabel Webb. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________________ History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society August 24, 2020 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ David Kaiser Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science (STS) Professor of Physics Thesis Supervisor Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Stefan Helmreich Elting E. Morison Professor of Anthropology Thesis Committee Member Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Sally Haslanger Ford Professor of Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies Thesis Committee Member Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ Graham Jones Associate Professor of Anthropology Director of Graduate Studies, History, Anthropology, and STS Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ -

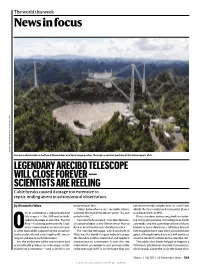

News in Focus ARECIBO OBSERVATORY/UNIV

The world this week News in focus ARECIBO OBSERVATORY/UNIV. CENTRAL FLORIDA CENTRAL OBSERVATORY/UNIV. ARECIBO A main cable broke in half on 6 November and tore large gashes through a central portion of the telescope’s dish. LEGENDARY ARECIBO TELESCOPE WILL CLOSE FOREVER — SCIENTISTS ARE REELING Cable breaks caused damage too extensive to repair, ending an era in astronomical observation. By Alexandra Witze mourning its loss. extraterrestrials might hear it, and from “I don’t know what to say,” says Robert Kerr, which the first confirmed extrasolar planet ne of astronomy’s most renowned a former director of the observatory. “It’s just was discovered, in 1992. tele scopes — the 305-metre-wide unbelievable.” It has also done pioneering work in explor- radio telescope at Arecibo, Puerto “I am totally devastated,” says Abel Méndez, ing many phenomena, including near-Earth Rico — is closing permanently. Engi- an astrobiologist at the University of Puerto asteroids and the puzzling celestial blasts neers cannot find a safe way to repair Rico at Arecibo who uses the observatory. known as fast radio bursts. All those lines of Oit, after two cables supporting the structure The Arecibo telescope, which was built in investigation have now been shut down for broke suddenly and catastrophically, one in 1963, was the world’s largest radio telescope good, although limited science will continue August and one in early November. for decades and has historical and modern at some smaller facilities on the Arecibo site. It is the end of one of the most iconic and importance in astronomy. It was the site The cables that broke helped to support a scientifically productive telescopes in the from which astronomers sent an inter stellar 900-tonne platform of scientific instruments, history of astronomy — and scientists are radio message in 1974, in the hope that any which hangs above the main telescope dish. -

Starry Messages: Searching for Signatures of Interstellar Archaeology

FERMILAB-PUB-09-607-AD Starry Messages: Searching for Signatures of Interstellar Archaeology Richard A. Carrigan, Jr., Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory*, Batavia, IL 60510, USA [email protected] 630-840-8755 Summary Searching for signatures of cosmic-scale archaeological artifacts such as Dyson spheres or Kardashev civilizations is an interesting alternative to conventional SETI. Uncovering such an artifact does not require the intentional transmission of a signal on the part of the original civilization. This type of search is called interstellar archaeology or sometimes cosmic archaeology. The detection of intelligence elsewhere in the Universe with interstellar archaeology or SETI would have broad implications for science. For example, the constraints of the anthropic principle would have to be loosened if a different type of intelligence was discovered elsewhere. A variety of interstellar archaeology signatures are discussed including non-natural planetary atmospheric constituents, stellar doping with isotopes of nuclear wastes, Dyson spheres, as well as signatures of stellar and galactic-scale engineering. The concept of a Fermi bubble due to interstellar migration is introduced in the discussion of galactic signatures. These potential interstellar archaeological signatures are classified using the Kardashev scale. A modified Drake equation is used to evaluate the relative challenges of finding various sources. With few exceptions interstellar archaeological signatures are clouded and beyond current technological capabilities. However SETI for so- called cultural transmissions and planetary atmosphere signatures are within reach. Keywords: Interstellar archaeology, Dyson spheres, Kardashev scale, SETI, Drake equation ACKNOWLEDGEMENT *Operated by the Fermi Research Alliance, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC02-07CH11359 with the United States Department of Energy. -

General Interstellar Issue

Journal of the British Interplanetary Society VOLUME 73 NO.7 JULY 2020 General Interstellar Issue PROTOCOLS FOR ENCOUNTER WITH EXTRATERRESTRIALS: lessons from the Covid-19 Pandemic John W. Traphagan & Ken Wisian WATER AND AIR CONSUMPTION ABOARD INTERSTELLAR ARKS Frédéric Marin & Camille Beluffi HABITABILITY OF M DWARFS: a problem for the traditional SETI Milan M. Cirkovic & Branislav Vukotic ON A SPECTRAL PATTERN OF THE VON NEUMANN PROBES Z. Osmanov REWORKING THE SETI PARADOX: METI’s Place on the Continuum of Astrobiological Signaling Thomas Cortellesi DYNAMIC VACUUM MODEL and Casimir Cavity Experiments Harold White, Paul Bailey, James Lawrence, Jeff George & Jerry Vera www.bis-space.com ISSN 0007-084X PUBLICATION DATE: 31 JULY 2020 Submitting papers International Advisory Board to JBIS JBIS welcomes the submission of technical Rachel Armstrong, Newcastle University, UK papers for publication dealing with technical Peter Bainum, Howard University, USA reviews, research, technology and engineering in astronautics and related fields. Stephen Baxter, Science & Science Fiction Writer, UK James Benford, Microwave Sciences, California, USA Text should be: James Biggs, The University of Strathclyde, UK ■ As concise as the content allows – typically 5,000 to 6,000 words. Shorter papers (Technical Notes) Anu Bowman, Foundation for Enterprise Development, California, USA will also be considered; longer papers will only Gerald Cleaver, Baylor University, USA be considered in exceptional circumstances – for Charles Cockell, University of Edinburgh, UK example, in the case of a major subject review. Ian A. Crawford, Birkbeck College London, UK ■ Source references should be inserted in the text in square brackets – [1] – and then listed at the Adam Crowl, Icarus Interstellar, Australia end of the paper. -

Dr. Steve Croft UC Berkeley Department of Astronomy, 501 Campbell Hall #3411, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

Dr. Steve Croft UC Berkeley Department of Astronomy, 501 Campbell Hall #3411, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA PERSONAL DETAILS Citizenships: USA and UK dual national Professional Memberships: Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, Member of the American Astronomical Society, Member of the International Astronomical Union, Member of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Member of the International Academy of Astronautics Permanent Committee on SETI EDUCATION 1998 – 2002 Oxford University, UK: DPhil (PhD) Astrophysics Galaxy clustering at high redshift from radio surveys. Advisor: Steve Rawlings 1994 – 1998 University College London (London University), UK: MSci Astrophysics MSci project: Magnetism and Accretion in AM Herculis Degree class: First class honours 1987 – 1994 Calday Grange Grammar School, UK (1994) A-level: Physics: A, Mathematics: A, Further Mathematics: B, Geography: A, General Studies: A, Music: C (best A-level results in school) (1993) AO: German for Business Studies: A (1992) GCSE: 10 Grade A, 1 Grade B (best GCSE results in school) (1991) GCSE: Mathematics: A EMPLOYMENT 2016 to date Associate Project Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley / Scientist VI, Eureka Scientific Project Scientist for the Breakthrough Listen project on the Green Bank Telescope. Leading the outreach, education, undergraduate internship (PI: NSF REU), industry and community engagement, and public data programs, in addition to proposal writing and scientific data analysis, for UC Berkeley SETI Research Center and for Breakthrough Listen. 2021 to date Adjunct Senior Scientist, SETI Institute (additional affiliation to UCB) Science with the Allen Telescope Array. Community Partnerships for SETI. 2012 – 2013 Researcher, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (with David Kaplan) - based at UCB Transient searches with the Very Large Array and the Murchison Widefield Array. -

Allen Telescope Array

Remaining schedule Previous Thursday Nov. 20: (nearly) finished up “Intelligence” material. Sec. 6.5, 12.2 in textbook. Today: Begin (and complete?) SETI searches: strategies, programs Textbook Chapter 12.3 Partial review sheet will be available over Thanksgiving break. Thursday: Thanksgiving break. Full review sheet online Monday, Dec. 1. Tuesday Dec. 2: Complete SETI material. Star Travel + Fermi paradox (ch.[13.1],13. 2, 13.3 in text) + review Thursday Dec. 4: Last day of class -- Exam 5. SETI web sites (“links” at course web site) SETI at Space.com http://www.space.com/searchforlife/index.html SpaceRef.com http://www.spaceref.com/Directory/Astrobiology_and_Life_Science/seti/ Ongoing SETI searches: SETI Institute/Allen Telescope Array http://www.seti.org/ Project SERENDIP, UC Berkeley http://seti.ssl.berkeley.edu/serendip/serendip.html SETI@home http://setiathome.berkeley.edu/ Sourthern SERENDIP, Univ. Western Syndey http://seti.uws.edu.au/ SETI Italia http://www.seti-italia.cnr.it/ Optical SETI at Berkeley http://seti.ssl.berkeley.edu/opticalseti/ Harvard http://seti.harvard.edu/oseti/ Amateur SETI: Project BAMBI http://www.bambi.net/ SETI League http://www.setileague.org/ Project ARGUS http://www.setileague.org/argus/index.html STRATEGIES FOR COMMUNICATION WITH EXTRATERRESTRIAL CIVILIZATIONS SETI is concerned with searches for signals from extraterrestrial civilizations, not spectral “biomarkers” we discussed earlier in course, or actual travel to other star systems (Ch.13). Except for 1974 signal to globular cluster M13 (thousands of light years away), we only try for reception, no transmission. (“What if they are all listening?”) “Signals” could be intentional (they are trying for contact) or nonintentional (we eavesdrop, one way or another).